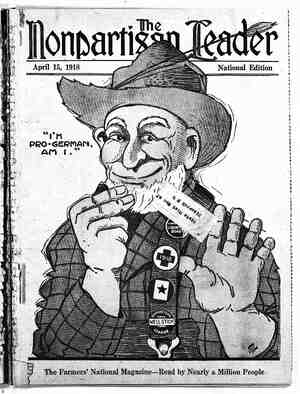

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, April 15, 1918, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

A Bid for Victory That Brought D‘efeat How the Farmers’ Movement of the Nineties Blossomed Into the Peoples’ AR ER 3 LAk Party and Quickly Withered When Plucked by Nebraska Democrats L Here, at the University of Nebraska, where people are proud of constructive radicalism, is being compiled a comprehensive history of the great farmers’ movement of the eighties and nineties, gathered from participants in those stirring events, who are still living. BY RALPH L. HARMON OWN in Nebraska farmers-have a very clearly defined notion of why it was that “the Populist party failed.” Outside of that state and a few others where farmers have kept alive to con- ditions, there is a sort of ‘gen- eral idea that it “failed” just because farmers are naturally so shiftless that they won’t “stick,” or that they are so narrow and selfish and soft-brained that they will trot off after any politician who carries their favorite label. Politicians have been busy for 25 years cultivating that idea, and today there are a great many sincere people who honestly think that. Then again some will tell you that “a move- ment like that” couldn’t help but fail because it was “based on class interest.” Still others say it “failed” because the. farmers became “prosperous” and that farmers’ movements haven’t anything to keep them together “except hard times.” Well,-if hard times drove the farmers together into a decisive movement, they at least were no different in that respect than the politicians of today, for the “hard times” that are now staring the politicians in the face have driven them to- gether into a bunch, so “patriotic” that they are willing to forget all “partisan divisions” and work together—to beat the farmers. But it was not hard times that ‘gave birth to the Populist party, nor was it the coming of “pros- perity” that caused it to “fail.” That party came into existence as other reform movements have, because there were glaring abuses that had to be corrected, because politicians, drunk with power, defied the people, flouted their requests and brazen- ly ran government in the interest of the railroads and corporations. Down in Nebraska they agree very largely with this view, but they have the actual proof there of how mere tactics may be fatal. The Populist party failed because of wrong tactics. BRYAN’S FRIENDS’ AND FOES’ DIAGNOSIS THE SAME A good many people in Nebraska will tell you this. Many of them will also add, “Bryan killed the Populist party.” This is said by some who are Mr. Bryan’s warmest friends, and is not meant by them as blame. Others say it with bitterness. Some “people think the Populist party “absorbed” the Democratic party and made it good. They point to the fact that it and Bryan adopted almost in toto the Populist platform, just as Roosevelt in 1912 adopted about half of the Socialist platform. These people think it was a good thing perhaps that the Populist party ‘didn’t live to a ripe .old . age of glory, such as the other two parties boast of. But there are some who don’t think the Dem- .ocratic party is wholly good.” They don’t think it got a big enough dose of reform. They think it has managed to throw off the effects. They think that the forward movement of that period would have developed into a great political party and would have displaced one of the others had it not - been for Mr. Bryan. Bryan’s friends and enemies are exactly alike in one thing: they go the limit. They are for him or . against him to the uttermost. And in spite of the fact that he has lost his grip on the Dem-. ocratic party machine in Nebraska, he still has his _ friends—many of them friends he won in those old Farmers’ alliance and Populist days. William Jennings Bryan came on the stage in Nebraska at the psychological moment. If he had happened to stop off in Iowa, when he left Illinois for the West, his whole career would probably have been different. Iowa had had its days of “agita- tion” and was reaching the time that the powers that be always speak of as “prosperity.” If, when he identified himself with a newly adopted state, ‘he had stopped east of the Missouri, he would have fallen into a different environment, and the whole history of the past quarter century might have "been different. You know “Full many a gem of purest ray serene, The deep unfathomed caves of Ocean bear; Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, And waste its fragrance on the desert air.” ~ But Mr. Bryan was not born to blush unseen, and though he lavished much fragrance (of ora- tory) on the desert air of the West, it was not wasted. He went across the Missouri river and - Arikara falls, near Valentine, Cherry county, Ne- braska, showing one of Nebraska’s still undevel- oped natural resources. There is vast water power in Nebraska, and most of ‘it has been “cornered” /./by corporations'that are holding it out of use await- - “ing the reaping of speculative profits. : ; “PAGE EIGHT - el landed among the radical Nebraskans then being scourged into political activity by the brazen thiev- ery of the railroads, and the cynical flouting of their political “leaders.” Mr. Bryan was a leader of a different sort. He was not a crooked poli- tician, he was not cynical. He did not flout the people. Instead of that he came among them decorously, quietly, like a modest young lawyer, never guessing the future that was in store for him. But he was gifted with oratory, fire, and a frenzy of sincere zeal when awakened, and, he- attracted notice by campaigning in 1888 for Cleveland. It was the next year that the famous get-to- gether conference of farmers’ organizations met at St. Louis, and the call they put forth for gov- ernment ownership of railroads and telegraphs; government funds to be loaned to farmers at low rates on their first mortgages and on ifionperishable farm products; abolition of national banks, and “free silver”; popular election of United States senators; the referendum and initiative—all these were progressive measures that he could heartily espouse. It is not calling him an “opportunist” to say that he made these issues‘also his. Mr. Bryan believed that the Democratic party could be reformed from the inside, and that by taking to itself the discontented elements from the Re- publican party, it could work itself into the po- sition of being the progressive party of the country. FARMERS’ PLATFORM OF_1889 BECOMES BRYAN’S IN 1890 < : So when he came out for congress from the first district in Nebraska in 1890 he came out on a platform very nearly like that the St. Louis farm- ers’ conference had tentatively put forth. That declaration of principles became the. fountain from which all the alliances in the western states that put up state and legislative tickets took the .cue. The wording of the platforms was very similar and their principles were the same. So, too,.the Nebraska state platform of the Democratic party \that year, which Mr. Bryan wrote with his own ~hand, ‘it is said, voiced’similar aspirations. And before the next election even, the Nebraska Repub- licans copied: it in part. : Mr. Bryan made the coinage question his main plank, whereas the various alliances- -were em- phasizing other features as well, and it is here where he began to exert'a turning influence on the then developing independent third party. He made a fiery campaign that year: He outdid his efforts of 1888 and won many by 'the sheer new- ness, sincerity and fire of his zeal. When the votes were counted Bryan had 32,376, his Republican op- ponent had 25,663, and the Alliance candidate only 13,066. It was the first time such an impudent thing had been done in Nebraska—a Democrat winning a place in congress. The Republican can- didate, an Omaha lawyer, was completely “flabber-" 2 gasted.” But that election opened the eyes of a lot of people. r The Republicans saw they ‘had no eternal hold on Nebraska. . Bryan saw his party was not a majority. ' The farmers saw they had not been able to win single-handed, although they had made a ‘magnificent fight for their first political effort. Thus the way was opened for fusion: later. This . was the election told of in last week’s article, when the -Alliance candidates were counted out by a combination of state Democrats and 80' that while they controlled the legi Republicans; - slatnre, they.