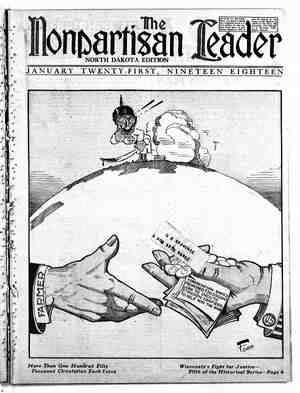

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, January 21, 1918, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

How Wisconsin Won-and Lost-Its Fight The Fifth Article in the Historical Series—A State That Made a Fine Showing Under Brilliant Personal Leadership, and Then Shpped Back Main héll, University of Wisconsin, at Madison. The university, during LaFollette’s administration as governor, was known as the most progressive institution in the United States. BY E. B. FUSSELL OMETIMES political progress comes through a thorough organization of the people—such an organization as the Farmers’ alliance ? movement and People’s party of the late 80's and early 90’s. Sometimes it comes through the gifts for personal leadership of some great advo- cate of the people, like George S. Loftus. In no state that the writer has visited has he seen such a striking example of progress through per- sonal leadership as in Wisconsin. . This doesn’t mean that there have been no organ- izations of farmers in Wisconsin. There are plenty of them. Wisconsin has dozens of different agri- cultural industries. It produces more cheese than any other state and tons upon tong of cream and butter. The farmers raise tobacco and sugar. beets to the value of millions of dollars, as well as corn . and small grains and livestock. Nearly all these industries. have their own organizations. The Leader has already told of the fights of the tobacco growers and cheese producers for free markets. The beet growers had a hard battle a few years ago when they were unable to get fair tests of their beets and the milk producers have a still stiffer scrap on right now. But all these fights have been ‘of separate industries. Big Business, ordinarily, has been able to keep ‘the beet growers and the tobacco raisers and the milk producers from getting together to right_their political wrongs. This has been in spite of the fact that in every fight they had, each class of farmers saw the need of having friends in the state- house at Madison. When the beet sugar men found the factory sugar tests were unfair (they were paid on the basis of the percentage of sugar in their beets) they asked the university authorities to make tests, as a check upon the factory tests. The university authorities refused point blank. The farmers say that at this time certain college authori- ties had interests in the sugar factories. The tobacco growers tried to get university help on methods for curing tobacco and preventing plant diseases, when they were fighting the tobacco trust. They didn’t get the help when they needed it. CITY WORKERS AND FARMERS DON’T CO-OPERATE At this writing the milk producers of Wisconsin, 100 of them, are defendants in injunction proceed- ings brgught by the attorney general, who alleges that they constitute a “milk trust” because they ask a higher price for their. milk than the milk distributors of /Chicago are’ willing to give.: There is no suit against the milk distributors for offering a lower price than the cost of production. Not only have the different farmers’ organizations been kept from co-operating with each other; they * have also been kept from co-operating with the organized workers in the cities. Political prejudice has done this. Most of the farmers are Republi- cans. Most of the men that the farmers elect to the legislature are Republicans; a few others are Democrats. . On the other hand many of the labor men in the cities, and most of the legislators they have elected, are Socialists. The natural lineup would be for the workers in the country and the workers in the cities to fight together. But they don’t. At the last session of the legislature the farmers and labor men together were nearly strong enough to con- trol the lower house. But they didn’t control. “You musn’t vote with the labor men—they’re SOCIALISTS,” the farmers were told, largely by Big Business papers. 3 “You musn’t vote with the farmers—they’re CAPITALISTS,” the labor men were told. And they generally voted against each other. This is-the fifth article in the Leéader’s series telling about the fight of the farmers and common people against the reactionaries and Big Interests in the states where the League is organized. Each week’s article is complete in it- self. You can begin the series with any issue. - You will want to read about the fight of the people in your state, but you will be interested in the history of ‘the fight in all the other states too. Mr. Fussell, Leader staff man, is gath- ering the facts for these stories directly on the ground. He is talking with the ‘‘old-timers’> who went through the old battles. Most of the men who took part in the great moves for a fuller measure of justice and democracy in the old days, are with the League today .—they see in the League the greatest force yet developed in the United States for bringing about complete rule o - the people. - Yet Wisconsin, for a period of about 10 years, was entitled to be known as the most progressive state in the Union. leadership of a few men and the support they re- ceived from the people, even without an_ organiza- tion to back them. The Grange and Farmers’ alliance movement at- tained considerable headway in Wisconsin and ‘in 1888 the farmers surprised the bosses by electing William D. Hoard as governor. But Hoard’s elec- tion, significant as it was of the real feeling of the people, didn’'t amount to jnuch. The Alliance had not gone into politics at this time and the Re- publican bosses were able to manipulate matters so that Hoard was defeated in 1890, before he had opportunity to accomplish anything in the way of reform. The railroads controlled politics in Wisconsin pretty thoroughly. Legislators and public officials, with few exceptions, rode on free passes and ship- ped their freight and express without charge. The railroads, on every $100 worth of property, were taxed less than half what a farmer was taxed on $100 worth of his property. There was elected in 1890 a member of the Wisconsin legislature named A. R. Hall, who thought this was wrong. He intro- duced bills in the legislature to do away with passes and to force fair railroad taxation. They were de- feated, but Hall kept on fighting. He offered reso- lutions on these subjects at the Republican state convention. They were chloroformed. Still Hall kept up his fight. A few more people. heard about the matter, each time Hall brought it forward, and joined his side. What had started ‘as Hall’s fight gradually became, the people’s fight. ATTEMPT TO BRIBE IN RAILROAD SUIT ! While Hall was making his fight a new figure came into prominence. This was Robert M. La Fol- lette. La Follette had been a district attorney. He had gone to Washington as a congressman, but had been defeated for re-election in 1890. La Follette had been known in Washington as a fair man, as a “reformer,” but not particularly as a foe of the railroads and special interests. The fact is that La Follette had not been in public life in Wisconsin, before he was first elected to congress, long enough to see fully the power of the railroads and how they - had corrupted politics. i But La Follette had an experience, soon after he returned from Washington and started to practice law. His brother-in-law and law partner had been - appointed judge, and was ig try e Py g ‘- o Saaa It was due to the personal