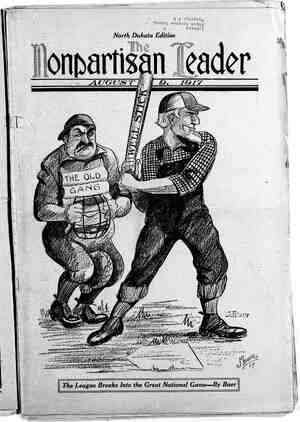

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 9, 1917, Page 11

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

¥ \ § & ¢ Another Article on the Co-operators of Wisconsin—Not All of the ; (Second article on Co-operation in ‘Wisccensin,) BY E. B. FUSSELL T WOULD be fine if all co- n operative enterprises in Wis- consin were so successful as the Sheboygan County federation and the River Falls elevators and creameries. But unfor- tunately co-operation doesn’t always work, even in Wisconsin, where it is given much more encouragement than in many other states. Take the co-operative creameries. ‘While they have eliminated one mid- dleman—the private cream buyer—the co-operators have to deal with another middleman, the New York or Chicago commission house to which they sell their butter. Dissatisfaction with the butterfat ratings given by the private creameries often led to the,organiza- tion of the co-operative creameries. Now these same creameries find a similar trouble in dealing with the lcommission houses. The commission houses buy butter from the creameries on an ‘“official scoring”. This scoring is made by an official scorer who is em- ployed for this purpose by the Butter and Egg Board in Chicago and by the Mercantile Exchange in New York. Both of these boards are organizations of commission men. The co-operative creameries have found in many instances that upon starting to trade with a commission house they get good prices for their butter but that this price would grad- ually fall off and complaints would come that the grade was not keeping. up. The commission man would send back reports from the official scorer to show that the quality was falling off. Then this creamery would change to another commission house anxious for business, and would get a good score and good prices again for a time. TWO DIFFERENT SCORES ON SAME LOT OF BUTTER One co-operative creamery in Wis- consin tried an experiment. The New York commission house which had been handling its butter was com- plaining of poor quality and difficulty in making sales. It was not getting good prices and was excusing itself by saying the butter was no good. An- other house was anxious to get some butter from this creamery and was promising good prices. Instead of sending all its butter to the new man the creamery split its next shipment into two equal parts, «nd sent one half to the old house and one half to the new house, rejuesting a scoring in each instance, \ The old commission house sent back a renort showing an official scoring of 86, made by the official scorer of the New York Mercantile Exchange. This indicated that the butter was of com- paratively low quality. The new com- mission house sent back ¢ report show- ing a score of 94. This is about as high a score as it is possible to secure. AND BOTH SCORES WERE MADE ON THE SAME BUTTER, THE SAMI3 DAY, AND WERE SIGNED BY THH SAME MAN! 5 The writer asked C. E. Lee, dairy specialist of the Wisconsin dairy anil food commission, how he explained such tactics. “There is just one answer,” said Lee. “The first commission man had more butter than he could handle. He didn't want to get any more so he tip- ped the scorer off that he didn’t want a high rating. The second commission man had plenty of customers in sight; he needed the butter and wanted to build up his business. So he either just let the scorer go ahead and give an honest score, or maybe hinted-that he wanted a high score.” SMALL ENTERPRISES - HAVE MOST SUCCESS Lee, by the way, believes that the co-operative creameries will never make the success that they should un- til they are shipping their product to a central distributing station that they own themselves located somewhere within Wisconsin, probably at Milwau- kee. Thus they will keep in their own Projects Have Succeeded—Packing Plant Fails control and within their own state an- other middleman’s operation, just as North Dakota farmers plan to keep control of their grain with a terminal elevator within their state, Anyone who investigates co-opera- tive enterprises in Wisconsin will he struck by one fact: The most success- ful enterprises, as a rule are the com- paratively small ones. Some of the best co-operative creameries have been organized in localities where lit- tle groups of Germans or Swedes or Danes have been colonized, have lived for years as neighbors and have be- come thoroughly acquainted with each other. One reason why co-operation works best with the smaller groups is that there is less chance for disagreement and misunderstanding among 20 men than 200. But another reason is that the expense of organization is less. The farmers at River Falls, for in- stance, did all their own organizing. So did the cheese manufacturers of Sheboygan county. But, "taking advantage of the repu- tation that has been gained by these co-operative enterprises, the ' profes- sional promoter has come into the Geld: IFor 10, 15, or 20 per cent, or sometimes even more, this gentleman will ‘come into & community and guar- antee to promote anything from a co- operative creamery to a co-operative pickle factory. He will sell the stock, ‘often making all kinds of 'misrepre- sentations” as to its probable earnings, pocket his profits and go on to the next town, leaving the farmers behind to build: up and operate a new business that they know little about, and mak- Wisconsin farmers attend dedication exercises . for Eureka co-operative creamery ing it necessary for ‘them not only to make legitimate profits, but enough extra to take care of the “watered” stock going as promoter’s profits, The next community, it may be, could get along very nicely by patronizing the co-operative creamery that: the pro- moter has already established in the first town. But this wouldn't do. FARMERS PROPOSE A PACKING PLANT “You don’'t want to det Mudville get ahead of you,”. says the ‘promoter. “They have.a creamery; you-ought to have one t00.” ¢ And so ‘by’ appealing -to the local pride a second creamery is-established, a second. set of promotion profits pock- eted, and the promoter mojes on, leaving two creameries, burdened by heavy promotion expenses, to ‘fight each other and two or three private creameries for trade that all ought to be handled by one creamery. Is it any wonder, under the circumstances, that some of the Co-operative 'enterprises go under, and give co-operation a bad name among the farmers? = Sometimes, too, downright dishones- ty enters inté deals and warnout prop- erties that can’t possibly make a pro- fit under private management are shouldered off onto co-operation at exorbitant prices. It makes any hon- est co-operator want- to paraphrase Madame. Roland and cry: “Co-operation; - what crimes are committed in thy name.” And in this connection must be told the story of the La Crosse co-opera- tive packing plant, even though -it is a sore subject in Wisconsin, In 1913 there was a “strong senti=- ment developing in the Wisconsin Society of Equity for a co-operative packing plant. Farmers saw- the big profits that were being made by the big packers and the idea of state ownership not occurring to them, look- - What the Dairy Farmer Fights ed around to see ‘what could be done in the way of co-operation. At that time it happened that there was a private packing plant at La Crosse, operated by the Langdon-Boyd company. It was an old plant, some of .its machinery had been installed for 30 years, and it was mot“doing the most profitable kind .of business. It had run up a debt said to be $55,000 at the bank and couldn’t get any more money to buy new equipment which was badly needed. UNLOAD PRIVATE PLANT- ON THE UNSUSPECTING Faced with this situatfon Andrew Boyd, manager under the private own- ership, had a brilliant idea. It was to unload the plant on to the farmers. Boyd first went to see Ira J. M. Chryst; a Wisconsin farmer who, besides being a leader in the state society, was na- tional president of the Rquity. The state convention of the Equity was to be held in La Crosse in June, 1913, and ‘Just before the convention met Boyd offered by letter to sell his plant to the farmers for $122,000, claiming thisg was much less than it was worth, In the light of what ‘happened after- ward, it appears that thig price really was about $100,000 too high. But in spite of a fight on the plan by Dr: Charles McCarthy ~ of~ Madison and Charles A. Lyman of Rhinelandery both connected with the National Ags ricultural Organization society Chryst’s influence was sufficient t carry with a whoop a resolution ins dorsing the scheme for the farmers tQ - (Continued on page 16) e 7 PAGE TEN : : : Scene in cutover land of northern Wisconsin. Millions of acres of idle lands largely level and suitable for cultivation, are in northern Wisconsin, but high prices charged by speculators and high interest rates operate to the disadvantage of farmers who try to reclaim these lands.