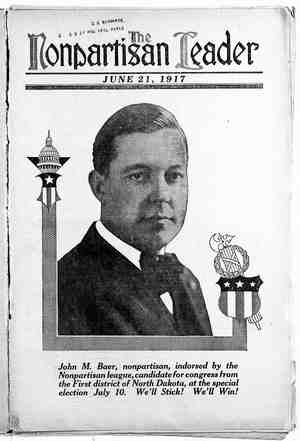

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, June 21, 1917, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

| bonds already issued, waiting to be 8old when the money was needed. ‘While we're talking about financing state-owned enterprises, it might be well to look at the revenue and ex- pense sheet for the last two years of the New Orleans terminals. In 1915, the total revenue of all the terminal facilities was $501,384.32, and the to- tal expense §485,804, leaving a gain for the year of $42,580.32. In 1916 the revenue was $682,564.38 and the ex- pense $526,612.47, leaving a gain of $155,951.91. The item of expense in- cludes all operating costs, interest on bonds, principal on bonds coming due and depreciation. The state-owned enterprises are standing on their own legs, without any help from taxation. ‘While this wouldn't convince anybody opposed to state ownership, because it is “Socialism,” it ought to prove that it is a pretty good business propo- sition, aside from the fact it frees the market place from the greedy conifol of private monopoly. RAILROADS PLAY A HOLD-UP GAME After eight years of public owner- ship and operation at New Orleans of the terminals—in 1908—the railroads were still playing a hold-up game. The public enterprises—wharves and warehouses—spread along the Missis- sippi river for many miles. No one railroad served all the various units of the terminal system. Each of the 10 or 12 lines running into the southern metropolis served certain parts of the river front, and a carload of freight going out or coming in often had to be switched over three or four or more railroads before it could reach or leave the wharf where it originated or to which it was consigned. This made it pretty fat for the rail- roads. Iach line would deliver cars coming in over its own tracks to the part of the river front tha: it hap- pened to serve, but if the car had to be switched to a part of the water frent served by some other line, every rail- road which touched the car in passing it along to its destination took a nice big toll. Switching charges at the ter- minals were all the way from $6 to $20 per car: The railroads wouldn’t get to- gether and make any reasonable agreement under which the switching could be done at somewhere near the value of the service. They didn't try to correct this abuse, because it was cash in their jeans not to. They should worry. Let the shipper pay it. But in this case the railroads were The railroads at New Orleans tri tem ther(_a by unreasonable switching charges. believed in public ownership, ed to destroy the usefulness of the state-owned terminal Sys- But the roads were up against a community that and the city of New Orleans built a terminal railroad of its own. Re- sult—fair switching charges. trying to put it over on a community that believed in public ownership, be- cause they had tried it and it filled the bill. The railroads played their hand too strong. Maybe they counted on a strong opposition in New Orleans against public ownership, which made them fecl safe that the people would not try to solve this question of the switching hold-up for themselves. If they did, they made a bum bet, for New Orleans stepped in with the club of public ownership and knocked tho unreasonable switching situation gal- ley west. DISMAL PLAINT MADE | BY THE RAILROADS ‘When the project for a municipally owned and operated public belt “line railroad, to connect up all the units of the state-owned and operated ter- minal system, was proposed, the rail- roads and the interests they could count on to fight for them set up a dismal plaint. What did the city know about owning and operating a rail- road? they asked. That was a business for the big magnates to conduct, and besides it was “Socialism,” if not “an- archy,” for the city to go into a pri- vate business of this kind. Oh, it was the same old yap that is raised every- where when it is proposed to solve economic abuses by the collective power of tne people. But New Orleans went ahead and built its railroad. A line was construc- ted all along the water front, connect- ing up all the terminals of all the railroads that entered the city and each unit of the public terminal sys- tem, in addition ty serving any num- ber of private manufacturing plants and warehouses. Sixty to 70 miles of track have been built by this city- owned railway. It is now possible to take a car coming in over any railway line and in one switching operation spot it at any point in the industrial district or along the water front. Tha city owns and operates 12 steam loco- motives on this belt railroad now. One ‘sees, them puffing busily about their work all along the 15 miles of developed water front, and each one is painted big with the words, “Public - Belt Line”—no doubt as to who owns and operates them. ‘What this publicly owned railroad did was {o make the switching charges at New Orleans $2, instead of from $6 to $20 per car. It's $2 now to switch a car from any point to any other point in the industrial and water front \ H—. . The high density cotton press owned and operated by the state of Louisiana at the public cotton warehouse at New Orleans. Compressors under private owner- ship formerly charged cotton growers excessive prices for compressing cotton, and no private press in the state was as good as this one belonging to the state. The sign on the press shows that New Orleans is not modest about its publicly owned enterprises. district, and the switching is done promptly and efficiently. Furthermore, A ship loading grain at the state_owned grair;n elevator at New Orleans. Ground is already broken for enlarging this elevator to a total of 3,000,000 bushels capacity. PAGE NINE the $2 covers all the costs, so that the line is self sustaining. Formerly the shipper or consignees had to pay the heavy switching charges. Now the charge is so low per car that the railroads absorb it in their regular tariffs and neither ship- per or consignee pays it. Public own- ership of the belt line has helped make New Orleans one of the cheap- est, if not the cheapest, port in ter- minal charges. Shippers gat a squars deal when they ship to New Orleans. The railroads now recognize that the city line is a good thing for them as well as for shippers. There isn't a shadow of opposition to it now. The railroads don’t have to monkey with cars consigned to points in New Or- leans other than those served by the line that brought the car in. They just turn the car over to the public line, which does the rest. The charge is so small that the railroads don't notice it. They don’t have any kicks from shippers about hold-up switch- ing charges. The whole industrial life of the city is benefited through the people taking over this switching business. And there is nothing left of the argument that a publicly owned railroad can not lucceed. Nobody even calls it “Socialism” now. THE CITY AND STATE WORK TOGETHER The belt line railroad, while owned by the city of New Orleans, is oper- ated in co-operation with the publicly owned terminals, which are state- owned, without any friction. The city has a commission administering the business of the railroad and the state has one administering the rest of the terminal system. The two work to- gether in perfect harmony. The rail- road was considered to be more of a city than state enterprise and the city instead of the state undertook to build and operate it. Special government investigators looking into the farm tractor situation, report that 34,371 new tractors will be ‘used this year on American farms. It is believed the actual number needed will run as high as 50,000. :