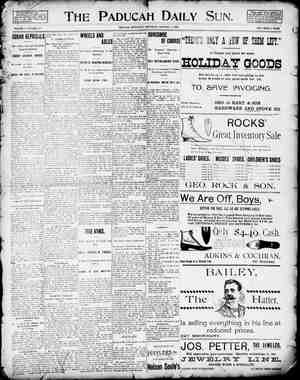

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, January 9, 1897, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

} © CHAPTER 1IX—(Continued.) He was an old friend, he explained, Mr. Ernest Norton, who had so un- untubly disappeared; and, having the advertisement inserted some me previously by some person called jana, he had come down to elicit such ormation as might be forthcoming eerniug his missing friend, and to offér his own services in the task of iseovering his whereabouts. }“You will understand, madam,” he ded, “that I am acting solely in my pacity as an old and dear friend of r. Norton, and, therefore, I am well ured you will give me every assist- ice in your power.” “Well .” replied the landlady, are welcome to hear all I know t the matter, though, as you're a friend of Mr. Norton’s I warn you be- forehand that it is very little to his credit. to say the least of it.” ‘How so’? queried Somerville. Whereupon M Baxter, nothing loth to have so willing and attentive a listener, told him all she knew about Norton and Zana, with such criticisms and comments upon that gentleman’s thrown in as her prejudices sted “Then you believe that he has sim- ply hidden himself or gone abroad to escape from this girl?’ suggested Som ille. “Certain sure of it, was the prompt reply. “There was a detective down here two days ago from Scotland Yard asking quegtions Mr. Graham,” “That Aceursed Zana Has Been at it Again.” just as you might be now, sir; and, al- though he didn’t seem to think much of my opinion at first, I think I pretty well convinced him I was right before he left. Why, Miss Zana herself, blinded as she was by her infatuation for the man, has come round to see him in his true colors at last. I'll just read you what she says in her very last letter.” “Well, I must confess appearances seem dead against my friend,” re- marked Somerville, when Zana’s letter had been read; “but then, you know, Mrs. Baxter, appearances are some- times deceptive, and we must not con- demn him too hastily.” “Oh, of course, you take his part, sir!’ exclaimed Mrs. Baxter, bridling. “Gentlemen always do back each other up wh¢re a woman is concerned: But if you can show me the smallest room for doubt in the whole dirty business I would like to know where it comes aH Downy it is affirmed that ne never went to the bank at all,” said Somer- Ville; “that he w in fact, personated some one els _“Which means that he simply sent this some one else to draw what money he required!” retorted the land- lady. “Had he gone himself he might have had to give his address, and that didn’t suit his little game. Don’t tell a 2 ie Air The plain English of it is that forton has behaved most disgrace- fully, and I’m sure my heart bleeds for that poor lamb he deceived so cruelly.” Somerville with difficulty concealed satisfaction which these outspoken caused him. If only the Scot- land Yard people should come to share them the whole affair would quickly drop out of sight. Even Zana had ed to believe in her lover, and had abandoned all thoughts of finding him! This was an unexpected stroke of luck. She whom he regarded as the most dangerous of all his possible adver- saries had voluntarily retired from the contest. “A good thing for her,” he muttered as he took his seat in the London ex- press, “for had she continued to edge on these detective fellows I would have risked a good deal to remove her from my path, Now I have only my wife to deal with, and, I flatter myself, I know how to manage her!” The next day found him at Scarbor- ough, where his wife welcomed him with delight, and his mother-in-law with that semi-atfection politeness asually bestowed upon a not very sym- pathetic son-in-law. “But, dear me, Richard,” remarked Mrs. Somerville, when they were alone, “how that hair you are growing on your face does alter you! I declare I shall not know you if you grow a full beard.” “It’s the fashion abroad,” he replied curtly, “and it saves me the trouble of shaving. Tell me, Helen, do you read the newspapers regularly down here?” “No, dear, I rarely see one. Mamma objects to them upon the grounds that they are always full of horrors and only stbscribes to a few religious pub- lications. Why do you ask?” “Oh, no particular reason,” he made answer. “I think your mother is quite right; ordinary newspapers ate not fit fiterature for women. By the way, you remember my friend Norton?” “Of course I do, Richard. I pray for im every day.” Somerville scowled; this sort of talk farred upon him. “Bother your prayers!’ he retorted prutally. “Norton don’t need them. But I want you to be careful never to gpeak of him or to allude to him as a friend of mine.” BY MAURICE H. HERVEY “Why, Richard, have you quarreled with him?” “Quarreled? Rubbish. The fact is, he has got into some scrape (over a girl, I believe) and he has deemed it prudent to keep out of the way for a time; in fact, he may never return to England at all. Certain persons are doing their utmost to discover his whereabouts, and not impossibly some- thing of the matter may some day reach your ears, or you may even see some reference to his sudden disap- pearance in a newspaper. I merely tell you this to put you on your guard. You know nothing whatever of Mr. Ernest Norton; do you understand?” “Yes; I am to pretend I know noth- ing about him.” “Have it that way if you like. Do you think Jane knew his name? She let him in, you know.” “No, Richard,” said his wife thought- fully, “I don’t think she did. If you remember, he did not wait to be an- nounced but burst in upon us like a whirlwind.” “Quite right, Nell,” assented Somer- ville approvingly, “so he did. Well, and how are you getting along down here?’ “Quite happily dear,” she replied. and comfortably, “Are you? Have you finished your work abroad al- ready?” “Tinished?’ echoed her husband, with a smile that was half sneer. “Why, I haven’t fairly commenced yet. I only returned for a couple of days to see after this business of Norton’s. I shall be off again so soon as your mother gives me something to eat.” Mrs. Somerville gave a little sigh, though whether of regret at the pros- pect of again losing her husband or of satisfaction at the promise of a pro- | longed holiday, she best knew. In the | end Somerville, having dined with her and his mother-in-law, departed Lon- donward, en route for Paris, feeling somewhat exhausted by such incessant traveling, but quite satisfied with the results of his hazardous mission. ‘I think I can afford to take things easily now,” he told himself as the Paris express steamed into the Gare | du Nord, “and, what’s more, I mean | to after all this bother. That Indian minx is satisfied, my wife is silenced, and—‘dead men tell no tales.’ I’ll just unbend for another month or so, and then I'll go in for a bout of steady, hard work. Strange, by the way, how lazy the possession of money makes a man feel. I don’t seem to be half so keen upon my researches as I was when I couldn’t pay the baker. Any- how, I’ve earned a holiday and I’m going to have it.” Did it ever occur to this cool, caleu- lJating brain that Richard Somerville the criminal was no longer the same man as Richard Somerville the honest, struggling practitioner; that, despite his worse nature, remorse would make itself felt? Who knows? The human heart is th deepest of all mysteries. Suffice it that Somerville was true to his resolve, and embarked upon a ca- recr of pleasure seeking with greater zest than ever. CHAPTER X, Trenchery, Miss Daisy. Fitzclarence was not the sort of young woman to miss a good chance when she saw one, and to her it seemed that her boldly-formed ac- quaintance with Miss Clifford might, if properly worked, present very con- siderable possibilities. “She’s a bit stand-offish and shy,” she told Mrs. Ratten, “but she’ll come round right enough by and by.” “Well,” remarked the landlady, “take eare you don’t go too far and frighten her off.” “Trust me for that,” returned Daisy. “I know what I’m about.” And she most certainly did know what she was about, so far as her own | interests were concerned. Within a few days she contrived to borrow fifty pounds from Zana, upon the strength of a plausible story, wherein a bedrid- den mother figured conspicuously, and she had even persuaded her twice for short walks. At first Zana demurred to these ex- cursions; but she was overdone by Daisy’s persistence. Since Ernest’s disappearance, life had become a blank to her; since the discovery of his sup- posed treachery it had grown to be a “He Is an Old Friend of Mine.” well-nigh intolerable burden. She grad- ually realized that her only hope of even temporarily stifling the deadly bitterness of her grief lay in forcing her thoughts into fresh channels. And moreover if she meant to fight down her sorrow and not to succumb, to live and not to die, it became clear to her that she must set herself some object, some work to live for. But what could she do? For what sort of work was she fitted? Miss Fitzclarence (despite the drawback of a bedridden mother) appeared to have solved the problem of a comfortable existence, and avowedly took a great interest in her. Could she do better, for the pres- ent, at all events, than follow her light- hearted new friend’s lead? One day, while out walking togeth- er, Miss Fitzclarence stopped to talk for a moment with a gentleman friend, whose appearance was so strik- ing that Zana, at the expense of being considered inquisitive, could not re- frain from asking her friend’s name. “He's and old friend of mine,” was the reply. “Something or other at one of the foreign legations, and his name is Ivanovitch. He’s a good fellow, and rich as Croesus.” But although Daisy made Zana the companion of her afternoon walks, she never invited her to accompany her at nights. They usually had 5 o’clock tea in one or other of the best places, and then she sent Zana back to Hammer- smith in a cab. “You see, my dear,” she would say, “I can’t take you with me to the the- ater where I’m engaged, and it would never do for you to wander about by yourself. When I get an evening ‘off’ we'll dine together somewhere.” “Perhaps, one of these days,” 72na once replied, with a sad little smile, “I shall ask you to get me an engagement at the theater, also.” “Yes?” cried Daisy, corsiderably sur- prised, but by no means displeased. “Well, let me know when you make up your mind, and I'll speak to the man- ager for you.” Thus matters progressed apace, and Zana daily became more vsed to her Before She Realized She Found Her- self Introduced. companion’s weys. Her heart, at first | so bruised and sore, had, moreover, by degrees, hardened toward Ernest Nor- | ton. A woman may, for a time, suffer keenly from the sting of despised love; but she will generally end by hating the man who so scorned her. One afternoon Daisy and she were caught in a shower, and took refuge in the Burlington Arcade, until the rain should cease. Many others had done the like, with the result that the nar- row avenue was somewhat crowded and movement a matter of some diffi- culty. As they stood thus, waiting. the ubiquttous Mr. Ivanovitch edged up to their side, and, before Zana well realized what was taking place, she | found herself introduced Apart from a slight foreign accent, Mr. Ivanovitch spoke English perfect- ly; he was an exceptionally handsome man, of the fair-haired Russian type; and he possessed in a high degree,that secret passport to a woman’s good opinion—tact. Had he known that Zana was by birth a princess, he could not have treated her with greater def- erence. “Well, dear,” remarked Daisy, half an hour later, “the rain shows no sign of stopping, and time is on the wing; so I think I had better put you into a cab and see you off to Hammer- smith.” “Hammersmith?” put in Mr. Ivano- vitch, quickly. “I am going in that di- rection, and my brougham is waiting in Burlington street. Will you allow me to drive you home, Miss Clifford?” “No, thank you,” replied Zana, a lit- tle irresolutely, for she was still la- mentably ignorant of English usages. “I think I would rather take a cab.” “Norsense, dear!’ protested Daisy, coming to the Russian’s assistance. “You'll travel far more comfortably in Mr. Ivanovitch’s brcugham, and, as he is going your way, it will not incon- venience him. Cone along.” Zana had a vague feeling in her mind that she would have preferred driving home by herself in a cab; but she did not see how she could well refuse the polite Russian’s offer without giving needless offense, and he, profiting by her obvious hesitation, settled the qatesiion by conducting her to the car- riage and opening tbe dcor. Refusal being now tantamount to downright rudeness, she got in; he followed, and they were socn speeding toward Ham- mersmith. Little was said during the drive; such few remarks as the Rassiax occa- sionally made were upon commonplace subjects, and his demeanor throughout was that of studied respect. Zana’s replies were couched in the fewest pos- sible words, and her manner one of distant coldness. When the brougham drew up at Mrs. Ratten’s, he shielded her with his um- brella until the door was opened, paused momentarily, raised his hat with a profound bow, and was driven —back to Picadilly; for, of course, his alleged mission beyond Hammersmith was pure fiction. Toat evening he and Daisy dined tete-a-tete. “You are convinced that the girl real- ly is as rich as you say, and that she carries the jewels and money about with her?’ said the Russian, during the progress of the meal. His eyes scintillated and his fingers twitched nervously on the snow-white table cloth. Could Zana have seen the expression upon his face at this mo- ment she would have failed to recog- nize in him the hand:ome cavalier who had acted as her escort an hour or two previously. Covetousness and greed, intermingled with an absolute determination to enrich himself at all hazards, stan:ped his features with a ferocity which would have been abso- Intely repellant to any but the one who was aiding him in his scheme. “Rich!” said Miss Vitzclarence, sub- duing her voice. “She is a veritable Croesus. Why, I have already had some fifty or sixty pounds from her, and there seems no end to her resourc- es. As to her jewels, I have an im- pression, from words which have es- eaped her, in spite of her reticence, that she is of Indian extraction, and that extremely valuable gems have been intrusted to her as the outcome of some policy connected with the heathenish rites of her religion.” “She is certainly, by no means, the first Indian refugee to whom the task of guarding such treasures has been intrusted. But have you seen them?” “No. More than once I have searched her rooms narrowly—too narrowly, in fact, to miss them had they been there. Llence, I come to the conclusion that they are secreted on her person. I understood that you had a well laid plot for discovering their whereabouts, but if you think Ican do so without alarming her, I will make the at- tempt.” “No, no. You’re extremely clever, my dear girl, but this matter is some- what beyond you. There must be no bungling. Once arouse her suspicion, and the game is up. I have a plan which I am confident will succeed,” and his small, ferrety eyes twinkled with excitement. ; “And that is?’ began Miss Fitzclar- | ence. “She inust be persuaded to dine with me here, and——” “At present I am afraid that is be- yond my ability.” “At present, yes. But we must work up to that end—play the affectionate and sympathetic friend. You leave the details to me.” “And a fair division?” “Trust me,” and for a moment 4 smile played around the edges of his thin lips. The following morning there arrived | a basket of the very choicest flowers, addressed to Miss Clifford, and accom- panied by a card, inscribed Sergius Ivanovitch, but bearing no address, and fresh floral offerings continued to pour in each day, but of Sergius Ivan- ovitch she saw nothing for nearly a week. “Here’s a pretty fix to be in, dear!” exclaimed Daisy, bursting into Zana’s room early one morning, in great ap- parent agitation. “You know that Mr. Ivanovitch, who drove you home and has ben sending you flowers? Well, | he has almost unlimited influence with our stage manager, and so I asked him to get me cast for a new piece in which | is a part I particularly covet, and which would be the making of me.” | “Well,” said Zana, listlessly, “has he | refused ? “Oh, no! On the contrary, he write: me to say-—here’s the letter—that he would gladly help me, but that he doesn’t exactly know how to set about it. Will I dine with him this evening and explan what I wish him to do?’ “That seems simple enough,” r marked Zana, striving to affect an in- terest in her companion’s aff “Yes, my dear,” assented Daisy, as- suming a very demure look, “it looks simple enough, as you say. But, you see, a girl in my position has to be} very careful about appearances. How ; can I dine alone with Mr. Ivanovitch, even though it is only to talk over a business matter?” “TI don’t know,” said Zana, stifling a little yawn. “Would it be thought im- proper?” “[’m afraid it would,” sighed Daisy, “and Mr. Ivanovitch, himself, evi- dently has his doubis, for he sugge: in a postscript, that perhaps Miss ( ford would honor him by accompany- ing me. Of course, if another lady went with me, no one could think or say anything.” “Then you must find someone else to accompany you,” rejoined Zana, “for I cannot go. “Do, dear! pleaded Daisy, coaxing- ly. “I shall love you ever so much if you will. You have no idea what a difference it would make to me to se- cure Mr. Ivanovitchs influence at the theater. And if (as you once hinted) | you should think seriously of the stage Saw the Russian Pour the Contents of a Small Vile Into Her Glass. yourself, it will make just as great a difference to you. You have evidently made a most favorable impression up- on Mr. Ivanovitch (the flowers prove that) and he will be greatly pleased if you consent to accompany me. If 1 bring anyone else, he will be disap- pointed and cross, and will revenge himself on poor me by refusing to back me up at the theater. Besides, you must see for yourself that there | ean be no possible harm in two young | ladies accepting an invitation to din- ner.” “N—o,” admitted Zana. harm in it, but——” “IT know!” put in Dai: quickly. “You don’: wish to do anything that might look like encouraging Mr. Ivano- vitch in his attentions toward yourself. I quite understand that. But, you know, you yourself, told me you would have sent the flowers back had you known his address. Why not take this opportunity to tell him so, and make him understand that such offerings are distasteful to you?” This sounded reasonable enough; | and the upshot of more persuasion and | coaxing was that Zana finally consent- | ed to accompany Daisy, upon the clear | understanding that no such request) would ever be made again. She and Zana reached Burlington street at half-past seven, where Sergi- us Ivanovitch and the brougham awaited them. Nothing could exceed the formal politeness of his greeting as he assisted them into the carriage and took the front seat himself. They were then driven through a succession of somewhat dingy streets, and finally alighted at a somewhat unpretentious hotel, which, however, the Russian as- sured them was celebrated for it cui- sine. They were evidently expected, for the landlord himself at once con- ducted them to a luxuriously-furnished apartment, upon the first floor, where couvers had been laid for three. Moreover, from the gorgeous display of plate, glassware and flowers, it was clear that neither the Russian nor the establishment had spared expense and trouble to do honor to the fair guests. From a gastronomic point of view the dinner was doubtless all that could be desired, though Zana thought it in- terminably long, with its ceaseless | “I see no | refrain from -s succession of courses. It struck her as a little strange that, throughout the, protracted repast, nothing had been | said abou her companion’s theatrical | prospects—which she had supposed ; would form the principal topic of con- But she concluded that the versation. theatrical business would be settled before they separated. “T notice that you have given us no champagne as yet,” remarked Daisy, skilfully dissecting an ortolan. “We are dining a la Russe,” laughed Ivanovitch, “and in Russia champagne is never served until the dessert makes its appearance. How English people ean drink it with their joints has al- ways puzzled me. However, have some now, if you like.” “No, never mind,” was the reply. You're dining us, and you shall do it your own way.” There must be an end to all things, even to a Russian dinner; and, in the fullness of time, the promised cham- pagne appeared with the dessert. A few minutes later a waiter entered with a telegram, which he handed to Daisy. With a few words of apology, she opened it, read it, and handed it to Ivanoyiteh. “What am I to do?’ she inquired, coolly. The Russian glanced at bis watch. “Take this,’ ‘he replied, handing her a piece of folded paper, half-irritably. “Rather smart practice, though, isn’t It? “One has to- be smart, nowadays,” she rejoined, covertly examining the folded paper. “You'll excuse my run- ning away for a few moments. won't you, dear?” she added, turning to Za- na. “I must send a reply to this both- ering telegram.” And, without await- ing any verbal assent, she hurriedly quitted the room. -Zana felt the situa- tion a little embarrassing; but she de- termined to profit by it, and speak her mind upon the subject of the flowers. “You have been sending me flowers, lately, Mr. Ivanovitch,” she said, cold- ly. “Pray do so no more. I would have returned them had I known your address.” “That is very 1 on the poor flow- ‘ers, Miss Cliff on me,” he answered, b “but, of hes and more. Will There is rner. I am Will you thing—while ig her tele- course, I shall r you do me a great piano over there in the jionately fond of mv me something—an Vitzclarence i Vigaeg Without a word Zana rose and went towards the piano, while he busied himeslt filling the glasses with cham- pagne. Now, above the piano, small hanging mirror, glance up at it, Zana pour the contents of her glass, which he immediately filled up with the sparkling wine. For a few moments Zana’s_ heart almost stood still. What was it this man had put into the glass destined for her? Did he intend to poison her, in revenge, perhaps, for her rejection of his flowers? Eastern stories of similar acts of vengeance flocked to her mind; but with them came the re- collection of how the would-be poison- er had sometimes been outwitted. ‘The same hard, set look settled on her face as had once so alarmed Mrs, Baxter. If treachery was intended she resolved that it should recoil upon its author. There was something of the tigress, as well as the lamb, in this Hastern maiden. “Do, pray, have a glass of wine be- fore you begin, Miss Clifford,” said Ivanovitch, persuasively. “You took absolutely none at dinuer.” “Thank you; I think I will,” she an- swered, returning to her former seat. Almost immediately she glanced at her left hand, and then raised the edge of the tablecloth. “I have dropped a ring,” marked, quietly. With prompt gallantry, the Russian at once stooped beneath the table to search for the missing ring; and, quick as thought, Zana changed her glass for his. Had he been less intent upon the success of his own villainous piot, Ivanovitch would have noticed the deadly pallor of Zana’s face as she raised the glass to her lip But he noticed nothing except that she was humoring him by drinking the wine. Truly, it was a wierd moment. He be- lieved she was sipping the contents of the vial, which she krew, when he set down his empty glass, he had swal- lowed himself. “Faugh!” that wine is too sweet for y palate!” he exclaimed, ms wry face. “But I believe ladi like a sweet wine; so it doesn’t matter. Come, Miss Clifford, drink it up. Sure- ly, one glass of wine can do you no harin.” To avoid argument, Zana drank the wine, and then went back to the piano to play as much as she could remem- ber of the “Moonlight Sonata,” glanc- ing occasionally at the tell-tale mirror and marveling much at Miss Fitzclar- ence’s protracted absence. The Russian poured himself out some more wine, and, finding it more to his taste than the previous sample, he kad several glasses in succession, listening, meanwhile, to the music, with a look of dreamy triumph in his pale-blue eyes. Gradually this look gave way to one that was almost vacu- ous in expression, and his head sever- al times fell forward, as though heavy with a desire for sleep. Presently he rose, stared vacantly around kim, and staggered towards a couch near the wall. A sound of réeling footsteps reached Zana’s ears, and then all was still. She closed the piano, advanced to she re- “Pledge me in Your Glass of Wine. the couch, and then the full treacher7 of these vile beings whom she had fondly looked upon as friends, burst upon her. Ivanovitch lay quite uncon- scious. But for the glimpse she had obtained of his movements in the mir- ror, and her consequent exchange of glasses, she would now be lying as helpless as he was--and at his mercy. Wer brain was in a whirl; but she re- gained suflicient composure to ring the bell. “Where is the other lady who dined here?” she asked the waiter. “went «iy in a hansom, miss, to sues Reais half an hour ago,” the reply. This Coontiematdl of vile duplicity was more than Zana, in her over- wrougt state of mind, covid endure: 3 “Tam going, also,” she told the wai er. The gentleman is lying asleep—ill or drunken, I know not which.’ 2a “Drunk he is, miss, and no mistake, said the man, approaching the inani- mate form on the couch. “However, I’m used to waiting on him, and Tl get him into bed, snug and comfortable. Shall I call you a hansom, miss, or will you use Mr. Ivanovitch’s brou- gam? It’s waiting outside, the coach- man having no orders to go yet.” “Neither, thank you,” said : Zana. “Or, stay—I don’t know the neighbor- hood. Get me a hansom, and tell the driver to take me to Charing Cross. “Well, if the Russian hadn’t turned his little finger up to-day quite so oft- en,” soliloquized the waiter, as he “What Are You Doi parted in search of the think you’d have seen © : Here. ab, “I don’t ing Cross vas Zana’s object in going to Charing Cr She had one, and one She knew that it was near the river. CHAPTER XI. The Bridge of Sighs. Big Ben was striking eleven when Zana alighted from the cab at the top 0 humberland aveaue, and walk- ed swiftly toward the Thames empank- ment. Her experience of life had been very, very brief. but it had been lengthy enough to convince her that on all sides were deceit and treachery, and, in her despair, life seemed but a lingering mise Her prefe: ig lover had deserted her— nay, he had not scrupled even to rob her as well; her professing friend, whom in her desolation she had trust- ed, had repaid the trust by engaging in a foul conspiracy against her. By following Ernest Norton to Eng- land she had made a return to her owi peuple impossible. To prolong her ex- istence in this cold, cruel country, eall- ed Englaud, would be exposing herself to further deceit, to fresh treachery. She saw but one means of escape from the terrible duplicity around her. “Father, forgive me, tor I know what to do!” she murmured; and, with th plaintive prayer upon her lips, she reached the stone parapet which sep- arated her from the dark-flowing river —the same Thames which had already received the body of the man she deem- ed had betrayed her. By the light of a lamp near Cleopat Needle she zed long and earnestly at the cold, eemed too close to m a little, and she herself in ud not tively of. heaving water. It her. She could s dreaded that if she threw from so small a height she sink, but would perhay battle for the life she so Vv Just then, tivo, a policeman close to her and eyed her su “What are you doing here? manded grufily. “fain looking at the ri una quietly; and, without any further questioning, ked quickly on. Presently she saw a row of lights stretching across the river; and she knew they must indicate a bridge. High up, too ,they seemed; high enough for her purpose probably far higher certainly, than the emban! ment. So she sped onward to Black- friars bridge. Just before she reached her destina- tion a ragged, wretcbed looking man besought her to buy an evening news- paper, of which he had several under his arm. . “ve only sold five since 7 o’cloc lady,” he added, by way of empk ing his appeal. “You look very poor,” said Zana pity- ingly. “Are you in want?” He did look very poor—as pitiful an object as one could well see. Moreover, he ap- peared to be suffering from a compli- cation of paralysis and some form of St. Vitus’ dance. His mouth was so distorted and drawn to one side that his words seemed to issue from a hole in his left cheek; his eyelids opened and closed with spasmodic rapidity, and he shook in every limb, except the right leg, which dragged behind him, rigid and well-nigh useless. Such sights are, alas! not rare in mighty London, but to Zana they were new, and her heart went out toward this poor cripple. “Am I in want?’ he repeated slowly, as though pondering over the words. am when I don’t sell the papers. You see,” he explained, lowering his voice to a confidential tone, “I’m not so smart as some of them at getting rid of my batch. A bit queer here (touch- ing his forehead significantly) and that is why they call me Daft Billy, I sup- pose.” 4 “Would money make your life hap- pier?” asked Zana. “Happier?” echoed the waif. “I don’t know that it would. But it would make me and Joe (Joe’s my mate, you know) more comfortable—less hungry and not so cold.” Without further comment Zana put her purse in his hand. Then from the bosom of her dress she drew forth a PpckerHea which she likewise gave im. “I no longer need these things,” she said, simply. “Be comfortable, poor man ,and less hungry, and not so cold.” And so left him, staring alternately at purse and pocketbook and at her re ceding figure. pau: piciously. he de- an waiting she (To be Continued) ® 5 4 r a , } it f } ; } 4 +s t ¥ | XV