Evening Star Newspaper, March 6, 1935, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

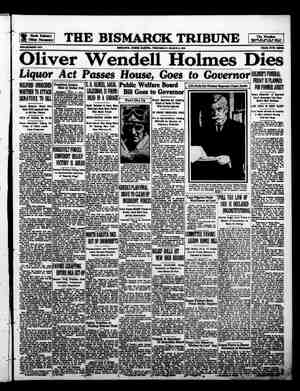

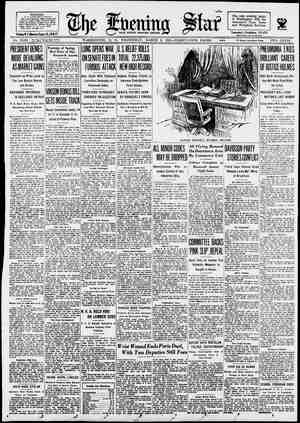

Course of Years Changed Holmes T Justice Holmes at Various Stages of His Notable Career From Great Dissenter to Rank|* Of Apostle of Human Rights Two Legal Generations Assessed Merit of Glamorous Jurist on Entirely Dif- ferent Basis—Views Become Guides. By the Associats LIVER WENDELL HOLMES, | oldest man to hold a seat on | O the Supreme Court of the United States, was “the great dissenter” to one legal gen- eration and the apostle of human rights as opposed to vested interests | in another. He lived long enough to have the Ppleasant experience of seeing views he | had expressed as leader of a minority. | become the guides of a majority of the high tribunal, a development which made for him a place all his own in the history of American juris- prudence. For close to half a century he served continuously as a judge, State or Fed- | eral, and only the physical burdens | of 91 years finally forced him to Write | his resignation. Beginning December 8. 1882, he was a justice of the Massa- | chusetts Supreme Judicial Court for | 17 years and then Chief Justice for | three years. From that post he was | elevated to the highest court in De- cember, 1902, by President Theodore | Roosevelt. He wrote his resignation | on January 11, 1932, Court’s Oldest Judge. ‘While he was the oldest justice ever to wear the robes of the high court, | he lacked five years of equaling the | service records there of Chief Justice | Marshall and Associate Justices Field and Harlan, each of whom served 34 years in Washington. But the judicial career of none of these equaled the mark of more than 49 years of court work established by Holmes. He brought to the Supreme Court & mind sparkling with genius inherited from a brilliant father; a mentality sharpened by legal study and jmbued with lofty sentiments to protect the vested rights of man in | the greatest tribunal of the world. | It was this last trait out of which | history probably will fashion its ped- | estal for Associate Justice Holmes as & member of that gallery of great men who have worn the robes of the Su- preme Court of the United States. Reared in an atmosphere of the best American traditions, Justice Holmes supported the rights of man as para- mount to property rights. He inter- preied laws as vehicles for effecting man’s will and consistently maintained throughout his long judicial career an | attitude which stamped him as a pro- gressive as distinguished from that school of thought commonly called conservative or reactionary. Fought for State Rights. He not oniy championed what he | considered the welfare of the people, | but ke fought to preserve State rights | against the constant trend to extend | Federal control. In the interpretation of laws he re- garded what he considered the object | which the people sought through them, rather than strict construction of the language of the statutes. He oppcsed‘» giving weight to language in a law over the motive and intent of its en- actment. A legal principle once estab- lished received his’ reinforcement | against technicalities. His personality was a remarkable combination of aristocratic habit and democratic mentality. Socially aloof, shy of publicity to the extent of shun- ning newspaper representatives, he was accessible {0 any one with court business and gave attentive ear to every cause. | He was punctilious in the observance | of all the demands of polite inter-‘[ course and never permitted a saluta- tlon to pass without response. He was particularly observant of such niceties | around the court, bowing with stately | grace to all who greeted him, never | failing to give a cheerful “good morn- ing” to the court attaches. From his father, author of “The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table” and whose full name he bore, and his mother, the daughter of a chief jus- tice of the highest court of Massa- shusetts, he inherited cheerfulness and | vivacity, sympathetic humor and wit. | He spoke with a pronounced Boston | accent and twinkling eyes, his face generally showing a friendly smile re- gardless of the cutting edge of his words. Seldom was he provoked into a frown. | Although thrice wounded in the Civil War, he was not materially im- | paired in health until 1922, when, after celebrating his eighty-first | birthday anniversary, he submitted to | two major operations. But they gave | him & new lease on life. Prior to that his friends were apprehensive that a wonderful career was drawing to a | close. i He resumed his judicial duties with his old-time vigor, showing as he ap- proached his 90th birthday anniver- sary none of the ravages generally | marking advancing years except a slight shoulder stoop from his former military carriage and the whitening | of his hair and dragoon mustache. A face youthfully pink defied wrinkles and his thick thatch of hair showed no signs of baldness. Well over 6 feet, with broad shoulders and ath- letic body, he had great dignity. md‘ personified distinction. Before the days of the motor car| his was a familiar figure on Pennsyl- | vania avenue, as he walked to and| from the court. With advancing years he was forced to forego such exercise and hired an automobile. | To the last he remained in har- ness, long after he had reached the age of retirement, declining, in the keen interest of his work, to lay it | aside for a life of ease. Opinions Classical | His opinions from the bench were | classics, gems of exquisite diction, the essence of brevity. appealing alike to layman and lawyer through their logic. They contained literary and judicial nuggets for those who looked under the golden surface croppings. Known widely as a dissenter, a des- ignation very distasteful to him, he had powerful influence among his col- leagues on the bench. Admiring him for his profound learning, they had great respect for his interpretation of the law, although sometimes disagree- ing with his conclusions. He published, with coplous notes, the twelfth edition of Kent's Com- mentaries, recognized as a standard text book, and for three years, early 1in his career, was editor of the Amer- ican Law Review. To it he contrib- uted articles and published, under the title of “The Common Law,” a serfes of lectures which he had given at Lowell Institute. He also published a volume of speeches, a collection of legal papers and wrote for the Har- vard uw!}!v}{:fi and the English rterly Law ew. Q?Y‘umue Holmes established a record for attendance on the sessions of the court. Meticulous in the discharge of his judicial duties, he kept a record of all motions and made generous notes during the oral argument of each case. These data were so complete that he had no difficulty in writing | his opinions, which he prepared in | tice Holmes had a common school ed Press. frequently interrupted counsel, always deferentially. He never nagged, brow- - beat nor unnecessarily interfered with their argument. At times some de- velopment would cause him to inject comment. Such occasions were looked forward to by his colleagues and court habitues for choice tidbits of wit and humor, as well as salient legal discourse. Many instances could be given in {llustration, but one will | suffice, | ‘While engaged in argument of mc| tobacco cases under the Sherman anti- trust law, a distinguished New York lawyer, counsel for one of the tobacco companies, considered it important, | in driving home a point, to declare that “nobody except fools and dudesi smoked imported cigarettes.” Justice | Holmes, with characteristic deference and smile, leaned forward and, with a delightful drawl, said: ‘Wit Is Displayed. “I am not so sure about that.| Sometimes I smoke them, and I know | I am not a dude.” Born in Boston March 8, 1841, Jus- education before entering Harvard, where he was about to graduate when the Civil War broke, in the Spring of 1861. He at once volun- teered, writing his class poem in camp and receiving his degree later. At Balls Bluff, near Washington, he was shot through the chest. On the battlefield of Antietam an enemy’s bullet lodged in his neck, and in & desperate charge on Maryes Heights at Fredericksburg, Va., he was wounded in the foot. = Entering the war a first lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, he earned a captaincy and was discharged with the brevet of | colonel. For a time he served as aide- de-camp to Brig. Gen. H. G. Wright. | He was only 23 when the war ended and he returned to Harvard. Within two years he had graduated in law] and engaged in private practice in Boston as a member of the firm of Shattuck, Holmes & Monroe until 1882, when he became a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massa- chusetts, of which his maternal grand- | father, Charles Jackson. had been a member. For two of the years de- voted to practice he was an instructor in constitutional law at Harvard. Married at Ag= of 31. At the age of 31 he married Miss | Fanny Dixwell of Cambridge. Mass. Their honeymoon lasted 57 years, un- til her death, on April 30, 1929. They had no children. The Civil War lived vividly in the memroy of Justice Holmes and he once said: “When the ghosts of dead fiters be- gin to play in my head the laws are silent.” After the Battle of Antietam a tele- gram went to Boston which caused much anxiety in the home of the young officer. It read: “Capt. Holmes wounded, shot through the neck:t thought not morfal; at Keedysville.” Dr. Holmes, already renowned as a great author of stirring verse, started at once for the bedside of his wounded son. But he failed to find him at Keedysville, nor could he get definite word of him in many another hospital and camp. He wandered through Maryand and down into Virginia, and was advised that his boy had been sent to a hospital in Philadelphia, and back-tracked to that city. But his search was fruitless. He returned to the fleld of military operations in the South, eagerly, but by this time almost hopelessly seeking his missing son. Then one day, while he was walking through a troop train, a bedraggled soldier addressed him with a quiet “How do you do, dad,” to which was given the equally calm re- ply of “How do you do, son.” This stoicism and absence of hys- teria was characteristic of the relation of father and son and of the outward attitude of each to the world. Yet the father could preach in his “Army Hymn”: “Thy hand hath made our country free; To die for her is serving Thee.” And the son could put that doctrine into practical application. Dr.Holmes wrote of his experiences on that mpl under the title, “My Hunt for the Captain,” published in the Atlantic Monthly at the time and puhlish:d' again a few years ago in an anniver- } sary edition. No bitterness from war experience rankled in the breast of Justice Holmes. While he fought against the Southern claim of the right of States to secede from the Union, he became later a stanch supporter of other State rights. When Chief Justice ‘White of Louisiana was presiding over the court a former Confederate offi- i | cer sought his assistance to have a case reviewed. The Chief Justice de- nied the request of his personai friend, advising that he should pay no more money on & losing cause. Other members of the court refused to grant the review and the litigant finally appealed to Justice Holmes, who granted the request as a compli- ment from a former Union officer to a former Confederate soldier. Always Saluted Foe. Justice Lurton of the Supreme Court was a Confederate veteran. It is the custom of the court for the justices in their robes to form a line and walk into court. headed by the Chiet Justice. The line passes be- hind a screen. Justice Holmes, as long -as Justice Lurton was on the bénch, always halted behind the screen, ! brought himself to attention and formally saluted his former foe as he passed. Modernistic in the development of ideas, Justice Holmes liked antiques. He had his office in his residence and fitted up the work room with a flat- top desk near a window and lined the walls with shelves of law books and books by his favorite authors. While he mixed them indiscrim- inately, all were located within easy reach. Valuable old rugs were thrown hap- hazard over a carpeted floor, with clothes carelessly strewn about. Over his desk was an old-style gas chan- delier with large glass globes, from which hung a toy skeleton, wired to dance when agitated. Numerous china ornaments covered the top of the desk. Nearby stood & “stand-up” bookkeeper desk, common in the days of his youth, with its slanting top and long legs. The furniture in all other parts of the house open to the caller was antique. Liked French Novels. More than one caller at the justice’s home was made aware by Mrs. Holmes of his fondness for French novels as mental recreation. She often directed them into the office with the remark, “You will find him there, reading one of those naughty French novels.” He also found relaxation in detective and Wild West stories. In his younger days he frequently ran to fires and longhand and never dictated. During oral argument of cases he A Mrs. Holmes liked to accompany him. Often in court he @ HolmesShunned Legal Terms; Homely Maxims Fill Decisions By the Associated Press. In his decisions, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, eschewed formal legal language except where it was necessary and used instead homely maxims. . Some were: A horsecar cannot be handled like & rapier. A man cannot shift his misfor- tunes to his neighbor’s shoulders. Most differences are merely dif- ferences of degree when nicely analyzed. Every calling is greatly pursued. The notion that with socialized property we should have women free and a piano for everybody seems to me an empty humbug. There is no general policy in favor of allowing a man to do harm to his neighbor for the sole pleasure of doing harm. One of the eternal conflicts out of which life is made up is that between the efforts of every man to get most he can for his serv- ices and that of society disguised under the name of capital to get his services for the least possible return. Value of Competition. Free competition is worth more to society than it costs. Nature has but one judgment on wrong conduct—the judgment of death. If you waste too much food you starve; too much fuel you freeze; too much nerve you col- lapse. Those traveling the road of life have at their command one and only one rule to success, to bring to his work a mighty heart. The man of action has the pres- ent but the thinker controls the future. Man must face the loneliness of original work. ‘We cannot live our dreams. We are lucky enough if we can give a sample of our best and if in our hearts we can feel that it has been nobly done. great when counsel of traps prepared for them. At times counsel are placed in the position of a witness by justices as under cross-examination. Often they have been rescued by the aged jus- tice, who, sensing their plight, would lean forward and, with his friendly smile, suggest, “If I were you, I would not answer that question.” or “I would not concede so much. Slang at times was employed by Justice Holmes and he sometimes convulsed the court by unexpected use of it. Once, while a case from Con- necticut was being argued, he sedately asked counsel several questions in classical language, pondered the re- plies for a moment and then gave his colleagues a hearty laugh by exclaim- ing, “That’s going some!” For years he was annoyed by fre- quent reports of contemplated retire- ment from the bench. To quiet them he wrote a friend declaring that as long as his brain and his health would permit he would remain at work. ‘When on October 4, 1928, he was| 87 years 6 months and 29 days old, he became the oldest man in point of years ever to adorn the august bench of the Supreme Court. Prior to that time Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney had held the record. ‘The longevity of Justice Holmes was attributed in large measure to regu- larity of habits. He usually arose at 8 am, breakfast at 8:45 on fruit, cereals, toast and coffee; worked from 9:15 to 11:30 o’clock on the days the court was in session, going then to the Capitol. At the 2 o'clock recess he ate a light luncheon brought to him from home, and on adjournment ‘at 4:30 p.m. took an automobile to his residence, where he worked until 7. After dinner he worked or read until 10:30 p.m. “Bowed to Inevitable.” Physical Infirmities *finally forced him to doff his judicial robes. He was in his accustomed place as the court went on the bench on January 11, 1932. He leaned forward, picked up some papers from the desk and de- livered the opinion of the court in the case of James Dunn against the United States. Dunn sought to have set aside the sentence imposed on him for violating the national prohibition law. Bowed over the desk by the ravages of advanced age, Holmes’ military mustache still bristled, and his ruddy face seemed flushed with health un- der his crown of wavy white hair. But when he began the delivery of the de- cision of the court which sustained Dunn’s conviction, he spoke in a weak, faltering voice, his pronunciation thick, It was the first time in his long career he experienced difficulty in completing a decision. Usually his words were clear and distinct and his enunciation perfect. Showing some signs of impatience over the difficulty he had experienced in reading the opinion, he yet gave no warning that the spectators had wit- nessed the end of his brilliant career. He remained throughout the session, ate luncheon with his colleagues and participated in the with his usual keen interest. But he walked from the bench never again to enter the court room for he went home, wrote to President Hoover, ’ Life is action, the use of one's powers. As to use them to their height is our joy and duty, so it is the one end that justifies itself. Life is an end in itself. and the only question as to whether it is worth living is whether you have had enough of it There is in all men a demand for the superlative, so much so that the poor devil who has no other way of reaching it attains it by getting drunk. We are all fighting to make the kind of a world that we should like. Others will fight and die to make a different world with equal sincerity and belief. The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. Constitution Experiment. ‘The Constitution is an experi- ment as all life is an_experiment. Great constitutional provisions must be administered with cau- tion. Some play must be allowed for the joints of the machine. Legislatures are ultimate guard- lans of the liberty and welfare of the people in quite as great a de- gree as the courts. The word “right” is one of the most deceptive of pitfalls—most rights are qualified. Congress certainly cannot for- bid all effort to change the mind of the country. Persecution for the expression of opinion seems to me perfectly logical. The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted. We should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the ex- pression of opinions that we loathe. When differences are sufficiently far-reaching, we try to kill the other man rather than let him have his way. A dog will fight for his bone. There is no basis for a philosophy that tells us what we should want to want. “The time has come when I must bow | to_the inevitable,” and resigned." The high esteem in which he was held by his colleagues was expressed in a letter they sent him when noti- fled of his action. They termed his service “a unique distinction in unin- terrupted effectiveness and exceptional quality.” “Your profound learning and philo- sophic outlook have found expression,” the letter read, “in opinions which have become classic, enriching the literature of the law as well as its substance. With a most conscientious exactness in the performance of every | duty, you have brought to our collab- | oration in difficult tasks a personal | charm and a freedom and independ- ence of spirit which have been a constant refreshment. While we are losing the privilege of daily compan- ionship, the most precious memories | of your unfailing kindliness and gen- eral nature bide with us, and these memories will ever be one of the choic- est traditions of the court. “Deeply regretting the necessity for your retirement, we trust that—re- lieved of the burd@en which has become too heavy—you may have a renewal of vigor and that you will find satis- faction in your abundant resources of intellectual enjoyment.” Afterward Holmes continued the life to which he had become accus- tomed outside the court. He read more than- ever, frequently visiting the Congressional Library and the Government museums. On fair days he rode in the automobile he had been hiring for years. ‘When the court took its Stmmer re- cesses he went as usual to his home at Beverly Farms, Mass., to remain there until the Fall. When the court re- sumed its sessions, he returned to ‘Washington. Justice Brandeis, his constant com- panion while he was on the bench, frequently visited him, as did other members of the court, some of them calling on him at his Summer home, as well as when he was in Washington. Often Toured Nearby Area. While ie never entered the room in which the court holds its public ses- sions, he several times visited the con- ference room where the justices meet to discuss cases and where he had on many occasions waged pitched battles with colleagues whose views differed from his. He always was careful, however, to time his visits so as not to encounter any members of the court in the council chamber. When he retired to private life he was entitled by law to continue to draw his salary of $20,000 he had been receiving as an active member of the court. This was cut to $10,000 by an economy act, but was restored to $20,- 000 by later legislation. Always a student, he found much in Wi to occupy his time. He loved trees and on his frequent auto- mobile rides went into the surround- ing country, having in Virginis & par- ticular grove of elms of which he was faithful secretary remained with him, 'a close companion. < HE EVENING STAR, WASHINGTON, D. €., WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 1935. HOLES' DISSENTS KEYTOPHLOSOPHY Career Revealed Conviction That Man’s Place Is “in the Fight.” By the Associated Press Known as the Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ phil- osophy was summed up in the words: “The place for a man who is com- plete in all his powers is in the fight.” ‘That conviction was exemplified in his life, first in mortal combat during the Civil War, then during his long years on both State and Federal benches. An uncompromising warrior against legal views he could not accept, his minority opinions frequently in later years provided guides for national policy. Hated Name of “Dissenter.” | In all his long experience on the bench only once did he stand alone. He hated the name the “Great Dis- senter,” and his record shows that while his dissents attracted much at- tention, he was found with the ma- jority of the court at least 10 times as often as with dissenters. Most of his best-known dissents came when the court divided five to four or six to three on some question of great national import. on the bench the two were generally tions, but in his dissents he frequently had the support of Justices Hughes, Van Devanter, McReynolds and other “brethren,” as he always called his associates on the bench. First Dissent in 1903. In his first dissent, rendered in 1903, | Justice Holmes stated he considered it | “useless and undesirable, as a rule, to | express dissent,” but he “felt bound | to do s0.” | Believing “the present has a right to govern itself as far as it can,” he | was no slave to tradition, and reached his conclusions on all questions pre- sented for decision by the application of his logic to conditions existing at the time. He never discarded doc- trines because they were new. With him the law changed to meet changed conditions. not merely the acquisition of facts but “learning how to make facts live.” He thought the height of intellectual ambition was to learn “to lay his course by a star which he had never seen, to dig by the divining rod for springs which he may never reach.” Last Decision in 1932. Justice Holmes rendered his last decision on January 11, 1932. It was a prohibition case in which James | Dunn sought to have his conviction iset aside by attacking the indictment as defective. The opinion was short, as Justice Holmes' opinions usually were. Speaking for the court, he re- fused to set the verdict aside. Justice Butler dissented. Justice Holmes' first decision was rendered within a month of his ap- pointment to the Supreme Bench. It was handed down January 5, 1903, in a case from California, in which he upheld the State law prohibiting purchases of stock of corporations and associations on margin. Two Jjustices dissented. Orle of his outstanding dissents was rendered in the case of Rosika Schwimmer, who was denied citizen- ship because of her refusal to take an unqualified oath of allegiance. Later, Mme. Schwimmer called on the aged judge to express her thanks for his support. Liked Murder Stories. In their conversation he explained he was taking life leisurely and ad- mitted, when asked about his reading, that he no longer cared to read im- proving matter, preferring to read murder stories. On leaving, Mme. Schwimmer expressed the hope of vistting him again.” His philosophy was shown in his reply: “If I live.” “Oh, do not speak that way,” his visitor urged. “You are younger than 99 per cent of others.” “Well, I am 92 per cent,” he re- plied, referring to his age. JURIST WAS NEIGHBORLY Town Where Holmes Spent Sum- mers Recalls Kindness. A little town in Massachusetts, Bev- erley, knew a different Oliver Wendell Holmes from the reserved jurist that most of the Capital watched from a distance. Justice Holmes spent his Summers in his modest residence in the Bev- erley farms district. One of his diversions was regular visits to see his old friend, the grade crossing tender at nearby Prides Crossing. And any resident of the section could testify that the jurist was & neighborly person, always will- ing for a chat on almost any subject > “Great Dissenter,” After Justice Brandeis joined him | Left to right: | boy.—Underwood Photo. Holmes Relived Found Pleasure in Visit- ing Old-Time Bat- tlefields. P made to Civil War battle scenes in and around Wash- |ington. to live over in reminiscence OIGNANT memories of count- less motor trips which former Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes The late Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes as a Pictured about 1900 when chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court.—Copyright by Pack Bros. As he appeared on the bench of the United States Supreme Court.—Harris-Ewing Photo. Out for a stroll after his retirement.—Star Staff Photo. Soldier Days | In Rides Around Washington | | his stirring experiences as a Union | | officer, are fresh in the mind of 61- | year-old Charles Buckley, chauffeur to the late jurist. “There was nothing he loved so much as to have me drive him to the battlefields where he fought for the Union,” Buckley disclosed in an interview. “You know, he was wounded three times during the war and he lost no opportunity to revisit the old forts and trenches where, as a young in- | fantryman, he battled against the | Confederates | "Nearly always he would take some | friends along with him and would (uu them all about the battle.” | Heard Tales of Wartime. | Buckley had heard those tales countless times during the 33 years he served Holmes, first as driver of & | chauffeur of an automobile. In the [pre-momr days, Buckley said, Holmes |hired a “rig” from Downey's livery | stable, which was on L street between | Sixteenth and Seventeenth streets. When the automobile came into its own, he first hired cars and later bought them. The car he used in Washington is a 7-year-old model of an expensive make, kept in perfect mechanical shape and appearanceg Buckley said the Justice liked this old car because | | it had “lots of head room.” in contrast | to the low, rakish lines of the present streamline era. Visited Fort Stevens. The veteran chauffeur said his em- | ployer visited old Fort Stevens, in Brightwood, more frequently than To Justice Holmes education Was | any other Civil War site. There, as | Gen. Lee. a captain of Infantry, attached to the | 20th Massachusetts, he aided in the repulse of Gen. Jubal Early, whose gray-clad troops were pressing peril- ously close to the Capital. President | Lincoln stood on the ramparts of Fort Stevens and watched the Union troops pike. | That was in 1864. Three years prior | to that, 20-year-old Lieut. Oliver Wen- dell Holmes, just out of Harvard, had marched along Pennsylvania avenue with the resplendent Massachusetts troops, keen for action. That regi- ment was fresh—its officers just out of Harvard and inexperienced. It | had never smelled gunpowder. The | trip from Boston, by boat and by train —by cattle car from Baltimore—had required 57 hours. Harvard Regiment in Town. The soldiers were tired as they marched in review before Lieut. Gen. | Scott. The streets were dusty and soldiers were everywhere. If Lieut. Holmes looked toward the Capitol he saw an incomplete building, with scaf- folding set up for work on the dome. The Monument was not half done— the stonework of the base rising out of the Potomac flats. Nobody cheered the new soldiers, for everybody was used to soldiers. Maybe an occasional patriotic son of Massachusetts raised his hat and yelled as he saw the “Harvard regiment” come marching along, uniforms spic and span and new, but its ranks only three-quarters filled. Camp was made that evening on the heights above Georgetown. It was the regiment’s first hike. Long years after, Holmes, as a mem- ber of the Supreme Court, retraced again and again that walk along the Avenue, and he must have recalled re- peatedly that great occasion in '61 when he marched forth to conquer the enemy. He walked every day to and from the Capitol—2 miles each way from his home—until he was 86_years old. Prior to his retirement from the Supreme bench, and subsequent thereto, Holmes had Buckley drive him occesionally over the Maryland countryside to Balls Bluff, a few miles from Frederick. It was there, in the Fall of '61, that he was carried, “mor- tally. wounded” as the surgeon thought, to the river bank after the first burst of gunfire from the enemy. According to Silas Bent’s biography of Holmes, it was on the 21st day of October, 1861, that Lieut. Holmes was standing with his men about half way up the slope of Balls Bluff. Con- the crest. A bullet struck the grognd and ricocheted, striking the lieutenant in the abdomen. He fell, his el ordered him to the rear. that came to L The house in which he spent his Summers originally belonged to his father. [ colon He crawled back and then found that beat the invaders back after a bitter | struggle along the old Seventh strm“ federate soldiers were firing fromp l CHARLES BUCKLEY. geant helped him to his feet, and, sword waving. he went back to the front line. Three minutes later and found on the same side of all ques- | hired horse and buggy and later as|another bullet struck him in the left | breast. just missing the heart. He i fell, regained consciousness on a barge | slowly making its way with the wound- | ed. under gunfire from the Confeder- | ates. to Harrisons Island, about 150 | yards from the Virginia shore. The wounded man next to him was groan- ing in mortal agony. “I suppose Sir Philip Sydney would say. ‘Put that man ashore firs the lieutenant thought. “I will let events take their course.” Aided Rockville Defense, Driving up the Frederick Pike, the justice no doubt often recalled the 6th v;()f September, 1862, when his regi- ment had, hurried out of Washington |and thrown up lines of defense near Rockville to await the attack from! terialize and a few days later young | Holmes, 21 and a captain and recov- ered from his wounds at Balls Bluff, with @ Summer of hard fighting in | the Peninsular campaign behind him, | was marching with his company to- ward the Monocacy and Frederick, where a parade was held before the enthusiastic citizens. From there the | boro, Keedysville to Antietam. The justice may have returned to the house in Keedysville, where, for several days after Antietam, he lay with a bandage around the bullet wound in his throat. He may have picked out the spot again where he climbed into a milk wagon in Keedys- ville and rode to Hagerstown, and perhaps he visited the home in Hagerstown where “some ladies saw him across the street, and, seeing, were moved to pity, and, pitying, | spoke such soft words that he wi | tempted to accept their invitation and | rest awhile beneath their hospitable roof.” Camped at Falmouth. Buckley said Holmes sometimes motored _to Fredericksburg, Va., | through Falmouth, just this side of the bridge across the Rappahannock. In November of 1862, the captain re- Jjoined his regiment, encamped there, and told his fellow officers of a dinner at “Parker’s” in Boston, which he had attended with nine other officers of the regiment. home with him on sick leave. One may imagine the envy with which the story of the dinner was heard—the anxious in- quiries of loved ones at home. The chauffeur would drive the justice along the wide, smooth pavement that now runs between Washington and Freder- icksburg, to the place on the hill above Fredericksburg where the Twen- tieth was encamped, or over the bat- tlefields of Fredericksburg and Chan- cellorsville, where, in May of 1863, he received his last wound from a bullet that crashed into his heel. Buckley recalls that Holmes once told a jesting friend it was not true he received this wound while running, but while lying on the ground. That was a long time ago—T70 years before he stepped for the last time from the bench at the Supreme Court, and, telling the attendant who helped him with his coat, “I won't be in to- morrow,” left his office at the Capitol. “The time has come and I bow to the inevitable,” he had written to the President. Neuritis For the reliet of chronie el M the’breath knocked out of him, and |y, he was not badly hurt—the bullet had not penetrated his uniform. A ser- } Mountain Valley Mineral Water Met. 1062, 1405 K N.W. ! | House minority leader: The attack did not ma- | | regiment marched on through Boons- | » AS NATION'S LEADERS EULOGIZE HOLMES Late Justice Ranked Among History’s Greatest by Congress Members. By the Assoclated Press. Expressions of sorrow at the pass- | ing of former Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes were combined today in the Capital with tributés to nis life and work. Here are some of the comments® Speaker Byrns: “There was not & member of the Supreme Court who enjoyed to a greater extent the es- teem, respect and confidence of the American people. There is behind him a -great record and every one, of course, will deplore his death.” Representative Taylor of Colorado, acting House majority floor leader: “I can say, speaking for the West arid for the lawyers as well as the public generally, that they regarded him as one of the greatest legal minds with a vast grasp of common humanity. They regarded him with profound re- spect and admiration. He combined a deep knowledge of the law with statesmanship, humanity and an in- terest in the welfare of the human Robinson Lauds Record. Senator Robinson of Arkansas, Democratic leader of the Senate “Mr. Justice Holmes was a great man. He was great not only in serv- ice as a soldier and as a member of our Supreme Court, but also in the quick and comprehensive grasp of es- sential legal and social reform. He witnessed and participated in many of the greatest movements and events connected with the history of our country. He enjoyed the confidence, the respect and the love of all who knew him.” Senator Ashurst of Arizona, chair- man of the Senate Judiciary Commit~ tee: “He was a brave soldier, an ex- cellent judge, a lover and critic of letters. He lived glamoursly." Senator Norris, of Nebraska, mem- ber of the same committee: “I can hardly express myself. His was one of the finest intellects that has ever lived. He was not only a great judge. he was also a philospher and it takes a philosopher to be a judge.” Senator Logan of Kentucky, former State Supreme Court judge: “He has been one of the greatest judges among the great judges that the United States has produced. The people of the Nation will be grieved at his pass- ing.” Senator McCarran of Nevada, an- other State Supreme Court judge: “In my judgment the former justice will be recorded in law in keeping with the position of his illustrious ancestor in the world of literature.” Representative Snell of New York, “He was con- sidered one of the greatest jurists in modern age and probably one of the most beloved members of the Supreme Court by the whole American people.” PNEUMONIA ENDS BRILLIANT CAREER OF JUSTICE HOLMES (Continued From First Page.) secretary of the justice, who stepped to the front door of the dimly-lighted residence to inform reporters waiting at the curb. The press representatives who had been keeping a 24-hour vigil fiom an improvised press room across the street, had sensed that death was near when Dr. Claytor made a hur- ried, unscheduled visit to the house at 2:10 am. | Others at the bedside were Mrs. | Edward Holmes, Prof. Felix Frank- furter of Harvard Law School, one of | Holmes’ most intimate friends: John {J Palfrey. friend and business ad- viser, of Boston: James Rowe, last secretary to the justice; Thomas Cor- coran, Reconstruction Finance Corp. |attorney, and former secretary toe KEolmes. and grief-stricken members of the household staff. Cold Started Tliness. ‘This group had been in almost con- i stant attendance at the house sinee a few days after Holmes was stricken with the cold which developed into pneumonia. He caught the cold, ap- parently, while on a motor ride ‘o Mount Vernon the day after Wash- ington’s birthday anniversary. To the stout-hearted nonogenarian, his ailment remained “just a cold” | after physicians had pronounced it | bronchial pneumonia, and he made light of drastic medical measures taken to ward off ravages of the disease. The consultations of physi- cians, the scurrying of nurses and the installation of oxygen apparatus he characterized as “a lot of damn-fool- ery.” At another time, before he lapsed into the coma which stilled his jesting, he thumbed his nose boyishly at a former secretary who passed near his bed, and at other times he joked with the nurses who adjusted his oxy- gen tent and gave him meager nour- ishment. : Medical Battle Futile. | For the last few days of his illness he had been breathing with labored | effort beneath a canopy filled with stimulating oxygen. Toward the close of the battle he had been unable to receive nourishment normally, and in« jections of glucose were administered at regular intervals, Dr. Claytor had had several con- sultations with Dr. W. T. Longscope of Johns Hopkins University and Dr. Lewis Ecker of this city. Every re= source of medical science was brought into play to combat the disease, but the advanced age of the justice was against him. At death he was devoid of relatives, except for his nephew and the latier's wife. ,The wife of the jurist died about five years ago. A OFTEN AT WIFE'S GRAVE Holmes Made Frequént Pilgrim- ages to Cemetery. Oliver Wendell Holmes made fre- tional Cemetery where his wife :lies buried. The grave is in a little frequented portion of the cemetery and few no- ticed the jurist. Ordinarily, he car- ried a single flower, a rose, a spray of honeysuckle, or a poppy, in his hand. He would place it on the gtave and stand for a few moments. The Holmes had ne children, WHIPPET-WILLYS AND . WILLYS-KNIGHT SERVICE ; 1711 14th'St. N.W. (Genuine Parts)