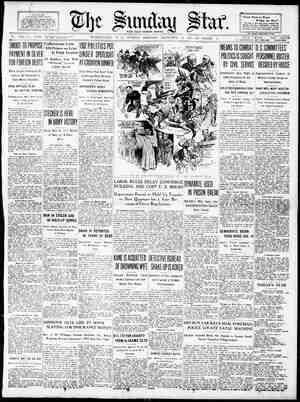

Evening Star Newspaper, December 13, 1931, Page 86

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

r2 WIS — s child could conceive, when once he was told about the seven-leagued boots, that there might be seventy-leagued boots. We can almost hear a little boy’s voice saying, “But I'm going to have seventy- hundred-leagued boots.” The vuice is more agreeable to listen to than that of the scientific prophet, and the calcula- tion is quite as easy. Indeed, the child has resources of real imagination which are quite untouched and untapped by the scientists, but that is a point to which I shall return later. The same fact which makes it inevi- table that these prophecies should be fulminated makes it quite the reverse of inevitable that they should be fulfilled. Indeed, the very fact that makes the prediction probable makes the fulfiliment impossible. The world most certainly never did, and almost certainly never will, go along the same road endlessly, or even to its extreme end. Progress in- variably alters, not merely its position but its direction, OOKS like these are like romances written for the court of the last Bour- bons, describing the grand monarch as growing grander and grander and his palaces more splendid. and full of tro- phies. In 40 years the palaces were pil- laged and the monarch had ceased to exist. But (what was much more im- portant) a new mood, once called the modern mood, 2 mood that did not care for monarchs or palaces, had set in; a mood of machinery and mer. money making. That modern mood is already passing. But its courtiers still write ro- mances about its gold and iron kings, and how they will soon storm the mocn and d their fleets to the stars; exactly as the old courtiers would have promised the French King, on the very eve of the French revolution, the spoils of Eldorado and Cathay. This scientific palace of dreams, or palace of nightmares, has already been shaken by a shock as abrupt as the fall of the Bastille. As in the other case, there has simply been an economic breakdown at the very base of the tow- ering ambition. The whole theory of modern trade and machinery has al- ready been turned upside down in the real revolutionary world, which is the mind of man. Scientists had multiplied production, only to be told that they had produced too much. Psychologists had instructed salesmen, only to be told that they had sold too much. Experts had made the very best machinery, only to be told that it must go on producing the worst goods as the only way of keep- ing it going. By this time such men have obviously lost their grip on machinery and money; both have gone mad and are merely de- stroying men. It will not last long. Man will escape somehow from such a lunatic asylum and the only question here is what use he will make of his liberty, Now, real imagination consists in imagining a new point of view; not in extending the stale scientific point of view into endless impossible perspectives. It is catching a glimpse of a new light on things; a new angle or attitude to- ward realties, which is new if only be- cause it is neglected. That is why really original men of genius have so often turned to ancient things rather than modern; as the Renaissance caught a glimpse of what the Greeks had meant or some modern artist of what the Egyp- tians had meant. And if I give a hint or two here of a happier society, at the very opposite ex- treme from the servile state of science, a world of men who produce to enjoy and not merely to barter, in which hu- man beings are heads in a workshop and not merely hands in a factory, I shall doubtless be accused of going back to a barbaric past and being content with the bare level of a peasantry. Some are aware that I am a distributist; one who would have most men owning and work- ing their own farms for food. And some may suppose that I only mean “going back to the old farm,” exactly as it was; stagnant or Puritan or left behind by progress. UT it is not so. I base my world on manly ownership, as the others base theirs on machinery. Just as they in dreams will draw out their machinery to fantastic lengths or rear on it toppling Utopias of electricity and steel, so I imagine many diverse developments and fruitful possibilities of the future that go far beyond this minimum of manhood. Take one mere hint, as a sort of starting point: The scientific Utopias are full of labor- saving machinery; sometimes saving men the labor of lifting a latch or walk- THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, DECEMBER 13, 1931. ing down a lane. It would be quite in that trite tradition to have clockwork armchairs to run about the room or electric pulleys to lift a man’s hat or haul him up to bed. Yet all this is rot- ten psychology to any one who has con- sidered the very meaning of the common words “play” or “amusements.” Look entirely on the joyful side of life, so to speak; concentrate on considering men and women as they enjoy themselves; their holidays, their pleasures, their sports and games. You will find running through all these, without exception, ex- actly the opposite principle to that of the labor-saving appliance. Work may be made as soft as possible. But play is made as hard as possible. An ideal commonwealth is always founded on making things difficult. Every pure amusement, at least of the most popular sort, has been founded on making things difficult. Nothing would be easier than to ask the man of science to construct a mechanical billiard table in which every ball would be automati- cally and accurately dropped into every pocket. The perfect billiard table would be much more labor-saving than the present barbarous practice of a gentle- man sprawling along a pointed pole, with one leg waving in the air, in the wild hope of making a very improbable can- non in a very remote corner; but the perfect billiard table would not be quite so like a game of billiards. Now, if we take a hint from the history of human pleasures, we may well specu- late as to whether we might not increase the pleasures by increasing the difficui- ties. We might ask whether the dinner table might not be made as exciting as the billiard table. We might wonder vaguely whether splendid strokes, or startling flukes, might not make the pepper or the potatoes more precious to us when they come. We might conjec- ture whether some ritual of chance or skill might make every meal a game as well as a meal. I do not go so far as to suggest that sausages or sardines should be flung from the other end of the table into the open mouths of the expectant guests; or that they should be formally blind- folded before plunging into the lark pud- ding or the bouillabaisse. This, indeed, might seem tinged with barbaric ele- ments, but human ingenuity would cer- tainly be equal to making a graceful game out of the feast if once it were started in that direction instead of mov-~ ing in the opposite direction. In other words, man would progress along the new path of sport and pleasure, just as he progressed along the other part of mechanism and monotony, if once he set his genius to work in that particular way. WE do not think of the thousand pos- sibilities now, because we always mechanically assume that nothing mat- ters, except getting the sausage as quick- ly and easily as po;sible from the sau- sage machine to the mouth. We are not in the mood to consider that a hundred merry jests might be played with it on the way, till it became as mirth-provok- ing as the sausage machine in the old English harlequinade, which cut up the policeman into sausage. I fear that in this example I shall be accused of levity; nor, indeed, do I insist on it with solemnity. But it does illus- trate a true psychological distinction; that there may be a progress of inven- tion in one direction, which actually pre- vents and forbids another sort of progress of another sort of invention in another direction. Take another aspect of sports and games; the way in which they are now organized over vast spaces from of- ficial centers. This probably improves the technique; it certainly adds inces- santly to the technical rules, instru- ments, methods and machinery, and that may be called a progress. All T say is that I'can imagine a totally different sort of pregress. I can imagine, for instance, the growth of new games out of the soil where they really grow; the spontaneous spirit of nurseries and natural playgrounds and all places where children are really at play. There was scarcely a family of children, at least in my own childhood, which did not have its own private and entirely original game; often doubled with a private and entirely original drama or romance. One group would always be sailing across the sea on a sofa to find an imaginary coun- try; another group would always be enacting the fortunes, and especially the misfortunes, of an imaginary family; an- other would turn its daly life into a con- spiracy by the constant use of a secret language; another would even break into pure intellectual creation by the des- perate maintenance of a family maga- zine, : Mow, all these things are inventions, exactly like fcientific inventions, only much nicer. 'or they are not only in- ventions, but, imaginations; and they come out of 4n imaginative soil of in- fancy which the scientific age has sim- ply never cultivated at all. I know that modern childien are sent to modern schools. I sugpect that the intelligent infant is, indeed, given his choice; his choice between the Mopperton Method in Nature Study and the Crotsky Course in Plasticine Thought-Forms, but not his choice between Google and Boogle, who were the joys and terrors of his nursery, if only for the perfectly simple reason that he would never dream of mention- The “Flag of Truce Boats” By Florence P. Percy N interesting incident of the Civil War was the “flag of truce boats.” Very few people of the present generation are aware of the fact that “flag of truce boats” were sent through the lines during the war of 1861 to 1865, carrying refugees to Southern ports, In this way families were re-united after weary and anxious months and years of separa- tion, suspense and exile brought about by war. These boats were commandeered for the purpose and were exempt from attack. As soon as the vessel was under- way the baggage, clothing and persons of the Southern passengers—men, women and children—were thoroughly searched for contraband articles. Gold and silver were not allowed to be taken through the lines and secret papers and other suspicious articles were carefully searched for. Even shoes and stockings were re- moved. One family had gold dollars covered and made into buttons, which were sewed on and ornamented their clothes. Much strategy and ingenuity were resorted to in smuggling treasured possessions through, sometimes success- fully. But the result was often disas- trous. The laws were very stringent and strictly enforced. Everything contraband was confiscated by the Federal aythori- ties in charge. It is told of one courageous mother and small son, who, in a frantic effort to reach Richmond, Va., from Wheeling, Va. (now W, Va.), experienced various setbacks and were obliged to make numerous detours en route. After ob- taining necessary letters to prominent people, one being to the Attorney Gen- eral at Washington, which were pre- sented as an opportunity occurred and under great difficulties, they started from Wheeling during the latter part of Sep- tember, 1861. The B. & O. Railroad had been cut and destroyed in places to pre- & vent the Northern troops from passing through, which compelled the mother and child to go up through Ohio, from there to Pittsburgh and then to Balti- more. A friend took them from Balti- more to Washington, where they ob- tained passes to Richmond. They then returned_ to Baltimore and that evening boarded a steamer going down the bay. The next morning, before dawn, they were put off the steamer and into a small “flag of truce boat” belonging to the North. From this they were transferred to another small “flag of truce boat” be- longing to the South, and from this they boarded a Confederate steamer, which took them to Norfolk, from where they were able to reach Richmond by train. The “flag of truce boats” were con- stantly used for transporting prisoners from point to point, but on only a few of the trips were refugee passengers al- lowed. As there was supposed to be no communication between the lines after war had been declared and an embargo proclaimed, many persons who were un- expectedly and unavoidably stranded and cut off from their homes and anx- iously awaiting a chance to ‘cross the Mason and Dixon line, seized with eager- ness the occasional opportunity allowed for passage on a steamer carrying the flag of truce. This enabled them to pass safely through the lines and to once more get in touch with friends or to join families. e e — ing such dreams when he got to school. They belong of their nature to the home, But in a healthier society, where the home had resumed its natural superiority to the school, a more intimate and in- tensive sort of education might make thousands of things out of this teeming soil of original imagination; new sports, new theatricals, almost a new mythology, as varied as the world of totems and household gods; yet perfectly compatible with a more serious religion of the peo- ple. As it is, the machine of modern or- ganized play plows up the garden that was a playground, and not only neglects, but prevents its growth. THESE are in their nature but faint and fanciful hints of the possibilities of a free commonwealth, for it would be far too free to have its future mapped out for it like the slave-state of the scientists. But the point is that I should expect a distributist democracy to develop, and not merely stick at that particular stage of compromise at which the old country life first found itself confronted and con= quered by the machinery of the towns. When I say that the simpler life of our ancestors was more on the right road, I do not mean that we are all bound to drink Aunt Susan’s cowslip wine and nothing else. But I do mean that Aunt Susan’s cowslip wine, in so far as it was Aunt Susan’s, and in so far as it differed from Aunt Hannah's dandglion tea, which was Aunt Hannah's, did in fact open gates of fairyland of freedom and variety as compared with the destruc- tion of all such domestic differentiation by the use of standardized goods. I will not launch forth into another fairy parable, in which wild and fantas- tic aunts shall caper about the garden gathering for us crocus wine or convol- vulus ale. I will merely note what the scientific sociologists, who are not wild, but tame, h2ve actually given us instead. They have given us a few fixed brands of infernally inferior Hquor. For the mo- ment I leave prohibition quite on one side. I am told that people sometimes do. Anyhow, drinks, whether hard or soft grow more and more monopolist and therefore monotonous. We should never expect new slogans, new advertise- ments, new methods of salesmanship, new theories of mass psychology, in or- der to sell the old wine; which (one may remark in passing) does not hap- pen to be wine at all. And even then, as I have said, we shall be told we have sold too much, and there are thousands of laborers in the vineyard. Another way of stating the case is to say that we have to return to a real in- dividualism, since at this moment capi~ talism is quite as remote from it as Com-~ . munism. No man can work out anything without a vast machinery of other men, of rich men to finance him and poor men to work for him. This spreads - everywhere a mere effect of sameness and regimentation; and individual mem- bers of individual families no longer fer- ret out things for themselves, because they can no longer find their reward in natural rumor and local curiosity; the whole countryside, so to speak, being dominated only by huge placards offering huge rewards for things done with huge resources on a huge scale. There is at this moment going on an enormous and anarchical waste of real inventiveness and imagination, merely because it will not fit in with the stupid simplifications of publicity and trade. I believe myself that a world of free fami- lies on free farms would be more active, more progressive and more prosperous than the present world of commercial organization. I am quite sure that it could not be more dull, more dreary or more inane. Yield of Pines Doubled THE difference of a half-inch means the dif= ference between 5 years and 10 years in the productivity of long-leaf pine in the Southern turpentine industry. Experiments carried on by Department of Agriculture experts over a period of five years in which three test areas were worked, indicate that the present commercial practice of mak- ing a three-quarter-inch slash in extracting the cleoresin is highly wasteful. In one of the test areas, the three-quarter-inch slash was used; in the second a half-inch slash and in the third a quarter-inch slash. In the case of the quarter-inch slash, the yield was as great as in the three-quarter inch and the quality of the product even superior. At the end of five years under the present system, the cut face was too high for further operation, while under the quarter-inch system at least five more years of operation was prace tical. The condition of trunks for lumbering purposes was much better also in the quarter- inch cut area, while the vitality of the tree was much greater.