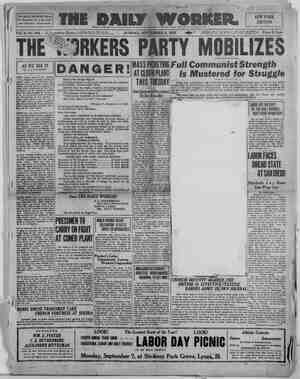

Evening Star Newspaper, September 6, 1925, Page 49

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, SEPTEMBER 6, 1925—PART 5 Ericsson, Througsh Monument Here, Placed Among America’s Great BY LUCRETIA E. HEMINGTON. N the eastern bank of the slow-moving Potomac, some 800 feet south of the flawless memortal to Lincoln, work- men have completed the | foundations for a monument to the Swedish-American, John Ericsson, the man who scrapped wooden warships for ships of iron; the man, too, who made it possible for Lincoln to main- tain uninterruptedly his blockade of the Southern ports, thus cutting off the outgoing shipments of cotton and the incoming shipments of the sup- vlies of war. It 18 not claiming too much for him when we state that his invention de- termined the issue of the struggle. Had the blockade of the Confederate ports been lifted and had England, under the resulting impression of the overwhelming strength of the South, thrown her support to their side, the war would have terminated in dis- union. The achievement of Erlcsson was a momentons, evoch - making contribu- tion to the science of war, and the value of his work is evident in the slte granted his memorial—for few, indeed, will be the monuments count- ed worthy of companioning the shrine of the immortal Lincoln. Even as its foundations rise, ready to receive the carved group of sym holic figures and the seated figure of the inventor, surveyors are busy within its immediate vicinity in lay- ng out the lines of the Arlington Memorial Bridge that, in the splendor of white marble, is to span the Poto- mac, uniting the Mall, with its fncom- parable memorials to Grant, Meade, Washington, Ericsson and Lincoln, in an indissoluble union with Arlington, rere sleep the men who have pre- served the Natlon's integrity. | One may, therefore, well question | & manner of the new memorial and | the manner of the man whom it shall Foundations Completed for Memorial on the Potomac, Where Inventor Bec / omes One of Company Including Washington, Linccln. Grant and Meade—His Monitor, Made Famous by Struggle With Merrimac, a factor in Deciding the Outcome of War—An Adopted American Whose Talent Had Previous]y Attracted the Attention of Royalty——A Naval Encounter Without a Parallel in History. commemc e, while to those consider- ations a glimpse of a real drama on | » sea shall be added. | Out of a block of marble weighing | 40 tons, from models made by James | F. Fraser of New York City, the | vdolino brothers will carve a group | of three magnificent figures in pro- nounced bas-relief. The female figure | directly above and back of the seated | form of Erlesson will symbolize the vision of the inventor who forever rendered obsolete the wooden walls of warring nations. The eyes of the fig- ure see beyond the present and into the future, stealing Prometheus-wise new knowledge for the race of men. It is nobly conceived and delicately executed, revealing its spiritual mes and meaning with marked clar- The veil that conceals from mor- vision is thrown back and the >s hold a revelation as yet unknown 10 _men. But on, on unaided knows no frul- so the sculptor has placed on left the spirit of Adventure, pan- lied as some early warrior, with et and shield and sword. A grim animates the figure; the ndsome face, with its wary eves and straightset mouth, the rugged muscles, and the drawn sword in the grip of steel, breathe no care- less playing with uncertaintles, but rather a determination to dare the un- tried and the dangerous with skill, that victory may be wrested from the struggle. That grim warrior, like the anclent Roman soldier, is about to carve out a new empire with his short sword, an empire of floating steel and iron, whose power shall make and unmake kingdoms and commonwealths at will. The grim warrior saves Vision alive, nd the two are restrained and made f service by the third figure, a figure ¢ Labor, that stands on the right of Vision. With what perfection of de- tail Is that earth-grazing figure placed on the right hand of her whose eyes see into the future. Somehow its rugged, honest toil will keep their feet on the ground, will transmute their brave, bold vision into a reality whose temper is that of practicality, of daily use, of service. * ok % % THE sroup’s trinity is in essential meaning & unity, even as the fig- | ures are 1 - separated and disunited, but each seeming somehow to be con- spicuous:of the support of the other. Tt is the unity of achievement, an ac- complishment whose significance is | not local or mational, but universal. | Tt is the spirit of the daring invention | of Erfesson, the precursor of a new epoch in naval warfare. With what appropriateness, then, does the sculptor place a seated figure | of the inventor directly below the sym- | holical group, his fine, sensitive face bent forward in thoughtful contem-| plation of the vision that dreams | above him. All his energy lives in | the clear-seeing eyes the | whole figure, save the head, showing a relaxation and a stillness that lets the brain leap from one pinnacle's height to another with faultless pre- clsion. The head of Ericsson is a master- piece. It will catch and hold the gaze of the beholder long after the mystic | charm of the symbolical group has faded out. It is a face, too, to delight those skilled in reading character from the feature. What leadership in | the fine high-bridged nose, what will | und determination in the chin, what power to dream dreams in the wides | set eves, and what a brow to house | the myriad thoughts. Yet always the 6 returns to the eves, for the soul's n is there, a true vision for the service of mankind. The memorial reveals much of the spirit of Ericsson. Let us turn to his lifo story to see how the years con- tributed to his achievement. 1¢ a group of 200 leading ditizens of ndinavian ancestry was able to versuade Congress to appropriate $35.000 (which has been increased by cifts from individuals of an added 25.000) for a memorfal to this man, what was the manner of John Erics. son, and what was the contribution that he made to the progress of this country that he adopted for his own? In this case s in the case of so many men of note, the boy was father of the man, for during his earliest Vears he showed a strong mechanical lLent. He was born at Langbanshyt- tan, Sweden, July 31, 1803, and at 12 vears of nage was emploved as draughtsman by the Swedish Canal o, His father was an Inspec- tor of mines, and the boy benefited from the scientific knowledge of the engineer in the family. He, himself, became fater in life an engineer of note, and one wonders what part _Lieredity played in his predilection for he laws of mechanics and what part ngsociation. Whatever gifts the gods &hook from their laps at his birth, not 1he least of them was his steady devo- tion to the work in hand . . devotion that resolved his vision the realities of new inventions. or seven years (1820-1827) he served in the army, and his maps 1d military drawings were of such axcellence that the king's attention was called to him, no small honor in those days when Kings still exer- cised authority, and the young roldier attained the rank of captain. On a leave of absence, he went to Tondon, where he learned of a prize to be awarded for the invention of « locomotive engine for the Liver- nool and Manchester Rallway. He formed a partnership with John Braithewaite and the two construct- ed the Novelty. It met with strong competition, however, for Stevenson's Rooket was there and carried off the prize. This was 2 most prolific period in 1he life of the young inventor. From his facile brain and hand came in- vention after invention. Perhaps the most noteworthy effort at this time was his plan for marine engines that #hould be operated entively beneath the waterline level, °When Capt. =t into “LABOR,” THE FIGURE WHICH STANDS AT THE RIGHT OF “VIS. ION” IN THE ERICSSON GROUP. (Sir) JoBA Ross set out in a journey into the Arctic regions in the Victory, his ship was equipped with such engines, but they proved un- satisfactory. Further study was need- ed to perfect the new idea. In 1832 his caloric engine was given to the public. % x " LTHOUGH he was unable to maintain the priority claim to the invention, he took out, three years later, a patent for a screw propeller, and the admiralty granted him one. fifth of the 20,000 pounds offered as a prize to the successful competitor. ‘There was, at this time, an effort being made to invent some method of protecting ships with iron. As early as the sixteenth century the Dutch had worked upon the plan, and at a little later period the French had made a similar attempt, so that the scheme was not new; no newer, in fact, than was the British inven. tion of armored tanks in the late war, for their prototype is found on ancient Babylonian_wall_carvings whose age | runs into the thousands of vears. A Capt. Stockton placed an order with Laird of Birkenhead for a small iron vessel, and the order stipulated that the engines and the screw were to be of Ericsson’s models. In 1839 that fron ship reached New York. Only a few months later Ericsson himself arrived in that city, took up his residence there, became natural- ized, and remained there the rest of his life, establishing himself as an engineer and as a builder of iron ships. Many difficulties beset his path, but slowly he won success and fame. When he died, his fortune was estimated at 50,000 pounds, no meager return in those days for his inventive genius. The greatest problem that his mind struggled to solve was that of ade- | quate defensive armor for war ves- sels. His plan for such a vessel made her lie very low in the water with her engines below the level of the sea, while she carried a revolving turret outfitted with one or two guns, whose turntable shifting obviated the need for maneuvring the boat since the guns could be fired from prac- tically any angle, while the enemy would have little to-aim at save the revolving circular turret which was incased in plates of heavy steel. The full meaning of his innovation may be realized when it is recalled that the fighting vessels of the middle of the nineteenth century were huge wooden boats, whose sides went tower- ing into the air, making excellent tar- gets for well aimed shells and whose clumsy engines made swift changes in position almost an impassibility. Tn 1854 Ericsson submitted his new plan to the emperor of the French, a man whose chief alm to play the role of the first Napoleon He succeeded in that his effort was mere acting, for it was sound and fury signifying nothing. As one might have expected, Louis Napoleon saw no merit in the invention which war- ranted his accepting it. Ericsson's op- portunity, however, lay closer home, as_events were to prove. During the American Civil War, the Norfolk navy yard fell into the. hands of the Confederates, who raised a number of the sunken frigates and restored some to use. One of these was to cause a strange commotion in the cabinet of the Federal -Govern ment, and was to give Ericsson hi; greatest opportunity fo ne. It v the hull of the Merrimac that was, when completed in its new and awful guise, to be rechristened the Virginia. ey 'HF report of the reconstruction of 1 Merrimac as an ironclad reached the ears of the Navy Depart ment of the United States, and imme- diately it invited proposals for plans of armored vessels. Among the re- plies was the plan of Ericsson. It was adopted because it was thought that his type of vessel could be used | on inland waterways as well as upon the sea. Work was begun upon the boat, whose completion was secured January 30, 1862. For this strange craft that looked more like a cheese box than any other thing, perhaps, an odd name was chosen by her creator. She was called the Monitor, for which name Ericcson, in & letter to the Navy, gave the following reasons: “The impreg- nable and aggressive character of the structure will admonish the leaders of the Southern rebellion that the batteries on the banks of their rivers wiH no longer present barriers to the entrance of the Union forces. The ironclad intruder will thus prove a severe “monitor” to those leaders. Downing Street will hardly view with indifference this last ‘Yankee notion,’ this Monitor."” In the interest of the Union, what A STUDY IN STONE. THE HEAD OF JOHN ERICSSON, FROM THE SEATED FIGURE OF THE MARBLE GROUP, med ta be | | | | Sweden, ADVENTURE.” ONE OF THE FIG! URES OF THE ERICSSON GROUP. a momentous hope was held out in that last sentence, for should Great Britaln ally herself with the Southern cause the Federal forces were doomed to failure. Ericsson played no small part in the drama_ of the Civil War, for he saved the Northern fleet and preserved to it the power of maintain- ing so close a blockade of the South- ern perts that supplies of food and raw materials, so necessary to States that had for generations produced but | cotton, were practically cut off. What more irrefutable proof of this state- ment was needed than lay in the empty knapsacks of the soldiers when Lee surrendered at Appomattox? It was evident from this letter that Ericsson was more than the dreamer, more than the inventor, for he pos- | sessed the vision of a statesman and | the patriot: of n for | the lar his adoption. In the opinion of experts, of the Monitor per se was greatly | overestimatgd because of the sig- nificance of the result of the fight be tween her and the Merrimac. As| a type, this boat did not prove as | serviceable as was expected, and it | was not long before her plan of con- struction was abandoned. During Ericsson’s last years his chief interest lay in the study of tor- pedoes and sun motors. When he died in 1889, his native government re- quested that the body be returned to | Because of the great esteem | felt for him and his service by Amer- | ica, he was accorded the signa of being borne home in the Baltimore. His body rests today Filipstad. His greatest memorial rises today | on the bank of the Potomac in the city he helped to preserve as the Cap- ital of a united country. And yet it would seem that he possesses a uni- versal memorial in the steel navies that swept the seven seas, floating | fortresses of ironclad strength, mount- | ing such mighty guns as Ericsson | never dreamed of. His is a lasting | fame—a fame made plangent by a| single naval engagement, the like of | which the world has never seen. Let | us glimpse its high points, since that | one action in Hampton Roads forever banished wooden vessels from the fleets of the earth. Rl AS already stated, the Navy De- partment of the United States was well aware that the Merrimac was under construction and read in the press, no doubt, upon her comple- tion, that she was, as an invention, | a failure, but did not know, could n know, perhaps, that by March 8, 186: she ‘would steam out in her slow, clumsy fashion, looking like a log house of iron rails with her peaked roof truncated on a line parallel with her eaves, toward the squadron of the United States frigates. Just off Newport News lay the Con- gress, Cumberland, Minnesota, Ro- anoke, St. Lawrence and smaller: ve sels fitted out for service. The Con- gress and the Cumberland. in a cleanly and festive mood, were flying lines of washing and a fashion sug- gestive of peace and not war. But those lines of sun-bleaching garments were suddenly lowered and more por- | tentous signals hoisted as a strange craft made her five-knots-an-hour progress into the midst of a whole squadron, Somehow it was like that famous single division of the British forces that charged the whole Rus- slan army. It was a bit breath-taking, to_say the least. Decks were cleared for action, ships were swung into position, and guns were trained upon her iron sides, but on she came, as fast as her en- gines permitted. She seemed, to those watchimk, somehow significant in spite of the fact that she was unaccom- panied and most unpretentious in size, It was a moving sight to see an iron- clad vessel challenge, single-handed, a whole squadron, for history had never been written in that epic gran- deur on the waves before. That strange craft carried 10 guns, 4 on each side and 1 at each. end of her iron cabin. “She could’ de- liver a broadside from her 9-inch guns and was capable of ramming the enemy, for she was built on the scheme of the ancient Greek and Roman galleys, her prow being pro- vided with an iron beak. The Merrimac, making direct for the towering Cumberland, whose guns the value at| it had so relentlessly made, and this| accident alone saved the Merrimac in the first act of her mighty drama. The Cumberland, with flags flying turned over on her beam ends, bravely firing to the guns against the invulnerable craft. This_success was a clarion call to | aground. The Congress put up a stiff | rimac now | defense, but after an hour's fight, her | though every hauled | citadel w the Confederate ships that steamed down toward the squadron, and they and the ram concentrated their fire against the Congress, that had beached her: of a friendly fort. The Minnesota, | SEATED ERIC “VISION,” THE FIGURE WHICH STANDS DIRECTLY BACK OF THE SON IN THE POTOMAC PAR}\;!IE\IOEIAL. | the Roanoke | beleaguered boat, but all three went decks running crimson, she {down her flag. | In the two engagements Federal loss in the Con- | If under the guns |federates had lost 60 men, while the | killed, wounded and |going last minute her futile [attempted to go to the rescue of the | and the St. Lawrence | drowned ran to 400. After hours of pounding by over 100 heavy guns, the armor of the Mer- was scarcely damaged, al- ing putside the iron destroved or washed away, hile she leaked a little where the iron beak had been torn away. Night was falling, the tide was out, and as she drew over feet of water, she withdrew for the day to return to her work of destruc tion with the morning and the tide ) THE Confederates were jubilant; they saw the hated blockade raised, and they hoped that England would now do more than smile In a friendly fashion upon their cause. In Wash ington consternation and despair reigned. Secretary Stanton actually went to the windows of the White House, expecting to see that fantastic death-dealing craft steam up the Potomac to do impossible damage. But fortune is ever fickle. A vol unteer crew was manning a stronger craft than the Merrimac, that, on hurried orders, was steaming toward Hampton Roads. It arrived in the night and stationed ftself close be- neath the lofty sides of the Minne sota, a veritable watchdog, strangely capable of sure defense. In the morning the Merrimac bore down upon the great Minnesota with the eagerness of assured victors for she was confident of repeating her success of yesterday. She was companied by Confederate vessels But her little, unknown antagon! like a wasp with a swift and deadl sting, darted out toward her, and, at a signal, the Confederate vessels with drew to a distance, that the two iron clads might have a clear field for their epoch-making struggle. Between those two groups of war vessels, the Monitor fought the Merrimac, a David against a Gollath, vet with |ea matched strength. Broadsides from the Merrimas rattled against the iron turret of the Moniter, whose turntable made her two guns do the work of the other's {ten, while the iron plates shed the stinging hafl of balls with little dan |age to the boat. The fight went on for hour | Finally the Merrimac tried to ras the Monitor, the attempt failing. | unwieldly was the larger boat ar quick the maneuvers of the smaller At last, like wearled antagonists the two ironclads seemed to realize that neither could conquer the othe | The Merrimac _joined her ships and the Monitor returned | the guardianship of the Minnesots {for it was fully expected that the morrow would see the struggle re | newed. | That expectation remained unfu {filled, however, and the battle r¢ mained a drawn one, o far as the fight of the ironclads was concerned Why the Confederates did not return {to reap the fruits of thefr victory is | one of the mysteries of the war. The Merrimac could have destroyed the Minnesota, but she did not make the |attempt It has been declared of that battle {that “its thrill was in its novelty; its s, in reconstruction of the {navies of the world.” The Government | breathed again, and blockade of the Southern ports to the ouragement of English interver sson was right; his li save the destiny of Wooden ships were ons henceforth wo r faith' no longer in wood but in walls of iron, magnif fleets, glant gu the sudden thrust stilettos of the sea, the s A c y and a q slipped past since the birth of Erics son, and today the alphabet of hi |genius is made of iron: greatest monument drez shrine of Lincoln at Washington maintained its tion. craft great put walls, cent han greater man’s f adopted his serv “We Will All Elope Together,” He Said, At the Climax of the Big, Modern Story BY STEPHEN LEACOCK. HE model novel,” says Prof. Somebody, ‘“‘must _depict life. It has got far beyond the point of mere story telling. The childish at- tempt to interest the reader has long since been abandoned by all our best writers. The modern novel must car- ry information, paint a picture, re- move a veil, or open a new chapter in human psychology. Otherwise it is no good.” I felt inspired, to try whether or not I could write a story to fulfill these difficult conditions. The reader 113 | may judge whether the story that fol- lows does so. It would be false mod- esty to conceal the fact that it was submitted for the $10,000 prize in gold offered by one of the biggest publish- ing houses. It didn't get it: TANGLED LIVES. 1 OMEHOW as they sat together on the deck of the great steamer in the afterglow of the sunken sun, De “Vere felt that he must speak to her. Something of the mystery of the girl fascinated him. What was she doing here alone with no one but her mother and her maid, on the bosom of.the Atlantic? Why was she here? not somewhere else? In the end he spoke. “And you, too,” he sald, leaning over her deck-chalr, “are going to America?” . : He had suspected this ever since the boat left Liverpool. Now at length he framed his growing conviction into Why was she she assented, and then ti it is 3,213 miles wide, is it not? " he said, “and 1,781 miles It reaches from the forty-ninth parallel to the Gulf of Mexic “Oh,” cried the girl, “what a vivid picture! I seem to see it.” “Its major axis,” he went on, his voice sinking almost to a caress, “is formed by the Rocky Mountains, which are practically a prolongation of the Cordilleran Range. It is drained,” he continued— “How splendid” said the girl. “Yes, is it not? It is drained by the Mississippl, by the St. Lawrence, and—dare 1 say it>—by the Upper Colorado.” Somehow his hand had found hers in the half gloaming, but she did not check him. ““Go on,” she said, very simply, “I think T ought to hear it.” ““The great central plain of the in- terior,” he continued, “is formed by a vast alluvial deposit carrfed down as silt by the Mississippl. East of this the range of the Alleghanies forms a secondary or subordinate axis from which the watershed falls to the Atlantic.” He was speaking very quietly, but earnestly. No man had ever spoken to her like this before. “What a wonderful picture!” she murmured half to herself, half aloud, and half not aloud and half not to herself. s went on, “there run railways, most of them from East to West, though a few run from West to East. The Pennsylvamia system alone has twen- ty-one thousand miles of track.” “Twenty-one thousand miles,” she repeated; already she felt her will strangely subordinate to his. “Through the whole of it,” De Vere1 raked her iron sides in vain, rammed her, the iron beak making a fearful gash in the wooden ship. She stag- gered, the Merrimac reversed her engines, but the beak refused to dis- lodge itself. Just as the great ship settled by the head, the iron beak broke off and remained in the wound He was holding her hand firmly z:lped in 'his and looking into her e. “Dare I tell, you,” he w! “how many employes it has?" ‘Yes,” she gasped, unable to resist. h “A hundred and fourteen thousand,” o said. The girl turned and faced him, | “Don’t.” she said. “I can't bear it Some other time, perhaps, but not now.” She had risen and was gath ering up her wraps. “And vou,” she | sald, “why are you soing to America?" “Why?" he answered. want to see, to know, to learn. And | when I have learned and seen and known, I want other people to see and to learn and to know. I want to write it all down, all the vast palpitating picture of it. In particular 1 want to try to analyze —no one has ever done it yet—the men who guide and drive it all. I want to set down the psychology of the multimillionaire!” He paused. The girl stood irreso- lute. She was thinking (apparently, for if not, why stand there?). “Perhaps,” she faltered, help you. “You! “Yes, T might.” She hesitated. —come from America.” “¥ou!" saild De Vere in astonish- ment. “With a face and volce like yours! It is impossible!” The boldness of the compliment held her speechless for a moment. “I do,” she sald. My people lived just outside of Cohoes. couldn’t have “‘Because T “I could e * he said pas- the girl went on, “but it's because I feel from what you have said that vou know and love America. And I think I can help you.” “You mean,” he sald, divining her idea, “that you can help me to meet a multimillionaire?” “Yes,” she answered, still hesitating. “You know one?" “Yes,” still hesitating. I rone.” know CHAPTER II. LIMITS of space forbid our describ- ing _in full De Vere's vain quest in New York of the beautiful creature whom he had met on the steamer and ‘whom he had lost from sight in the iaigrette department of the customs house. his folly for not having asked her name. Meanwhile no word comes from her, till suddenly, mysteriously, unexpect edly, on the fourth day a note is handed to De Vere by the Third As- sistant Head Waiter of the Ritzmore. It is addressed in a lady's hand. He tears it open. It contains omly the written words, “Call on Mr. J. Super- man Overgold. He is a multi-million- aire. He expects you.” To leap into a taxi (from the third story of the Ritzmore) was the work of a moment. To drive to the office of Mr. Overgold was less. The por- tion of the novel which follows is per- haps the most notable part of it. It is this part of the chapter which the Hibbert Journal declares to be the best piece of psychological analysis that appears in any novel of the season. We reproduce it here. “Exactly, exactly,” said De Vere, writing rapidly in his notebook as he sat in one of the deep leather arm- chairs of the luxurious office of Mr. Overgold. “So you, sometimes feel as if the whole thing were not worth ‘while.' “I do,” said Mr. Overgold. “I can't help asking myself what it all means. Is life, after all, merely a series of immaterial phenomena, self-developing and based solely on sensation l.n(! re- action, or is it something else?” He paused for a moment to sign a check for $10,000 and throw it out of the window, and then went on, s - ing still with the terse brevity of a man of business, ; “Is sensation everywhere or is there perception, too? - On what grounds, if any, may the hypothesis of a self- explanatory consclousness be - re- - jected?” “Exactly,” sald De Vare. A thousand times he cursed | | bonds in his desk. They both paused. Mr. Overgold had risen. There was great weariness in his manner. It saddens one, does it not?” he said. He had picked up a bundle of gold bonds and was looking at them in con- tempt. “The emptiness of it all!" tered. ere. “Do you want them,"” shall 1 throw them aw: “Give them to me,” id De Vere quietly. ““They are not worth the he mut- He extended the bonds to De e said, “or | throwing.” 0, no," said Mr. Overgold, speak- ing half to himself, as he replaced the “It is a burden that I must carry alone. I have no right to ask any one to share it. But come,” he continued, “I fear I am sadly lacking in the duties of inter- national hospitality. My motor is at the door. my house to lunch.* On arriving at the house De Vere was ushered up a flight of broad marble steps to a hall fitted on every | objets | side with almost priceless d'art and others, ushered to the cloak- room and out of it, butlered into the lunchroom and footmanned to a chair. As they entered, a lady already seated at the table turned to meet them. One glance was enough—plenty. It was she—the object of De Vere's impassioned quest. A rich lunch gown was girdled about her with a 12 o'clock band of pearls. She reached out her hand, smiling. “Dorothea,” said_the multimillion- aire, “this is Mr. De Vere. Mr. De | Vere, my wite.” CHAPTER 1L E' this next chapter we need only, say that the Blue Review (adults only) declares it to be the most daring and yet conscientious handling of the sex problem ever attempted and done. They stood looking at one another. “So you didn't know?” she mur- mured. In a flash De Vere realized that she hadn’t known that he didn't know and knew now that he knew. He found no words. The situation was a tense one. Nothing but the woman's innate tact could save it. Dorothea Overgold rose to it with the dignity of a queen. She turned to her husband. “Take your soup over to the win- dow,” she said, “and eat it there.” ‘The millionaire took his soup to the window and sat beneath a little palm tree, eating it. “You didn’t know?” she repeated. “No,” sald De Vere. “How could ‘And yet,” she went on, “you loved me, although you didn't know that I ‘was married?” “Yes,” answered De Vere simply. “I loved you in spite of it.” “How splendid!” she said. - “Does he know, too’ asked De Vere. “Mr. Overgold?" she said carelessly. :inl-?"l'pm he does. Kt apres, mon French? Another mystery! Where and how she had learned it? De Vere asked himself. Not in France, cer- tainly, “I fear that you are very young amico mio,” Dorothea went on care- lessly. “After all, what is there wrong in it, piccolo pochito? To a man's :nl;nd perhaps—but to a woman, love s love,” “But come,” she broke off gayly,| “don't let's be gloomy any more. I want to take you with me to the matinee.” “Is he coming?” murmured De Vere, nodding toward Mr. Overgold, Pray let me take you to | | “Silly boy,” laughed Dorothea. “Of | course” John is coming. You surely |don’t want to buy the tickets your | self.” The days that followed brought strange new life to De Vere Dorothea was ever at his side the theater, at the Polo Grounds, in the park, everywhere they were to gether. And with them, buying seats and reserving tables, was Mr. Over gold. Thus the three formed together one of the mos perplexing, madden ing triangles that ever disturbed the society of the metropolis. * At * x % 'HE denouement was bound to come. It came. It was late at night. De Vere was standing beside Doro thea in the brilliantly lighted hall of the Grand Palaver Hotel, where they had had supper. Mr. Overgold was busy for a moment at the cashier’s Dorothea,” De Vere whispered, pas ionately, “I want to take you away from all this. I want you.” She turned and looked him full in the face. Then she put her hand in his, smiling brave will come,” she said. Listen,” he went on, “the Glori tania sails for England tomorrow at midnight. I have everything ready Will you come “Yes,” she answered, “I will.” And then passionately, “‘Dearest, I will fol low you to England, to Liverpool, to the end of the earth.” She paused in thought a moment and then added: “Come to the house just before mid night. Willlam, the second chauffeur (he is devoted to me), shall be at the door with the third car. The fourth footman will bring my things—I can rely on him; the fifth housemald can have them ail ready—she would never betray me. I will have the under gardener—the sixth—waiting at the iron gate to let you in; he would dic rather than fail me.” She paused again on: “There is only one thing, dearest that 1 want to ask. It is not much 1 hardly think you would refuse it | such an hour. ‘May I bring my hu |band with me De Vere" Then she went satd Dorothea “You don't know how I've grown tu value, to lean upon, him. I like to feel wherever 1 am—at the play, at restaurant, anywhere—that T reach out and touch him. I know, she continued, “that it's only a wild fancy and that others would laugh at it, but you can understand, can you not, carino caruso mio? And think darling, in our new life, how busy he, too, will be—making money for all of us, in a new money marki It's just wonderful how he does it. A great light of renunciation lit up De Vere's face. “Bring him,” he sai “I knew that you would say that. she murmured, “and listen, pochito pocket-edition, may I ask one thing more, one weeny thing? William, the second chauffeur—I think he would fade away if I were gone—may | bring him, too} Yes! O my darling, how can I repay vou? And the smc- ond footman, and the third Botae- maid—if T were gone I fear that none B “Bring them all,”" said De Vere, half bitterly. “We will all elope to. gether!” (Copyright, 1925.) Bright Boy. Grandmother—Johnny slide down those stairs. Jobnny—T know 1t. I wouldn't You couln't.