Evening Star Newspaper, August 20, 1925, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

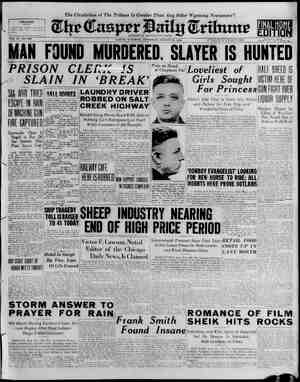

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

G Sl STAR idition. THE EVENING ‘With Sunday Morning WASHINGTON, D. C. THURSDAY.....August 20, 1925 THEODORE W. NOYES. .. .Editor The Evening Star Newspaper Company Business Office: f 11th St and Pennsvivania Ave, } New York Office: 110 East 42nd St. * Chicago Office: Tower Building. European Office: 18 Regent St. London, England. The Evening Star. with the Sunday morn- ing edition. ia delivered by carriers within ihs City at 60 cents per month: daily only. 45 cents per month: Sunday only. cents per month. Orders may be sent by mail or telephone Main 5000, Collection is made by er at the end of each month. car Rate by Mail—Payable in Advance. Maryland and Virginia. Daily and Sunday. Daily only. Sunday only Dafly and Sunday Dall Sunday only Member of the Associated Press. The Associated Press is exclusively en to.the tie for Tepublication of all news ¢ Pacchies cradited 10 ft o not yiherwise cred: i this. paper and also the local new: Danliehed Betin. Al rishts of publication nes herein are also reserved. Victor F. Lawson. Victor ¥. Lawson, foundes and publisher of a great newspaper, whose death occurred last evening in Chicago, was of the foremost American journalists, for more than half a century a leader in that field in his own city, and an influential factor in the country’s newspaper de- velopment. In 1876 he est: blished a partnership with Melville E the publ ion of the Chicago Daily News, of which he later became the sole proprietor. His whole life was consecrated to building a great new paper dedicated to the public welfare. His industry was remarkable and his success one of the most notable in American journalism. In the develop- ment of the Daily News, Mr. Lawson created an organization of exceptional efficiency. He recognized and secured the services of workers of unusual ability, developing one of the most brilliant newspaper staffs ever assem- bled, including men who have become famous in various lines. Mr. awson was a citizen of the best type, holdin the highest ideals and practicing them in his daily life end his business activities. A devoted son of his native city rove always for its betterment and against the tendencies of evil which beset it. He used his newspaper for the good of the community. He was true to a high standard of American journal- jsm, uncompromising and yet pro- gre: He rendered great service to the ne’ apers of the United States in his connection with the Associated Press, of which he was one of the founders and its first president. An indefatigable worker, unsparing of himself, he literally gave his life to the service of his newspaper. He in- spired the loyal zeal of all his asso- clates and helpers by his own example of unflagging industry. He was a modest man, shy of publicity con- cerning himself and his works, and a ‘most generous man, giving freely and largely to worthy causes without per- mitting public knowledge of his bene- factions. In his half century of active pub- lishing service, Victor F. Lawson made newspaper history, strengthened the foundations of the best type of American journalism and set an in- spiring example for all people by his unswerving devotion to his trust as the publisher of a great journal, rep- resentative of the best in American civilization, always devoted to the pub- lic ){00(1. one ve. ————. What valuable practical knowledge may be obtained from Arctic explora- tion is still to be shown. The interest in such events is in the adventure rather than in prospective utility; an interest up to now more popular than sclentifi 5. ————— The MacMillan Party. Postponement of effort by the Mac- Millan exploring expedition to carry out its main purpose has been judged d le or nec because of in- ability of the aviation section of the expedition to find suitable landing beaches and also because of storms. August weather in the far North is extraordinarily severe. For some time reports of this tenor have been coming by radio from the explorers, and aban- donment for 1925 of effort to reach the Pole and map the circumpolar region has hinted. Disappointment is felt by scientific tlons and by a certain part of the public, which enthuses over any form of exploring adventure. A majority of people will be unmoved by the post- Few grasp the reason which prompts men to risk life by in- ling extre upper and nether parts of the earth in the hope of gain- ing scientific honors and bringing back certain ot It is believed that the principle on which the MacMillan exploration pol- fcy is based is practical, and that the airplane is a better means of crossing polar wilds t he dog sled or snow- shoe. Tt is believed that when avia- tion bases and landing places are found it will comparatively safe and easy to gain extensive knowledge of the region. It is desired that the seas be mapped sounded, the character and more learned of the currents. The land will be mapped and the mountain ranges, if will be plotted measured. The geology of that part of the world will be investigated. It will be determined if the Arctic region once had a tropic climate_and what forms of life now extinct at the Pole existed there. Great gains in knowl- edge of terrestrial magnetism may be made, and the riddle of the magnetic pole, far from the geographic pole, may be solved. In the land, icebound for perhaps millions of years, and perhaps unseen by any representative of our species and certainly by-no man of what we call our civilization, may lie riches of coal, gold, copper and iron which may put the human race on a higher plane of living. ‘With postponement of the chief pur- pose of the MacMilian party, the ex- plorers will turn to closer inquiry of the interior of Greenland, Labrador #nd other north lands. The indented sary men ponement a ne ervation: T be and any, and and organiza- of their bottom discovered; coast of Greenland, from the §0th de- gree of latitude to the 80th and from the 20th degree of longitude to the 55th and 65th, 1s sprinkled with place- names. The north part of the coun- try above the S0th degree has been visited by elvilized man, and there are Washington Land, Ball Land, Nares Land, Pearys Land, Hazen Land, Erickssen Land and Northeast Fore- land. From the 25th degree of longi- tude to the 50th and 60th, and for more than 1,000 miles north agd south the map of Greenland is a flaf, empty space, yet the topography is probably like that of other parts of the earth and is filled with mountain ranges and valleys, and its resources are not known, From parts of the island news is now and then brought to the coast towns that there are stone buildings, burial heaps and other things showing a remote-time occupancy by a white race. Here are clues to Northmen settlements in America, and the Mac- Millan explorers will look into this. East of Greenland across Baflins Bay is Baffins Land, little known, ahd be- tween the Arctic Ocean and Baffins Bay is a frozen empire of large and small islands, named, but of the sur- face of which a few miles back from the sea little is known. There is a vast field for exploration in the North. ————— Tariff and Textiles. President William Green of the American Federation of Labor threat- ens to bring organized labor: down the Republican protective tariff, particularly as extended to the tex- tile industries, unless the textile manufacturers let up in their wage reductions. Labor in this country, like the manufacturers, has ‘benefited enor- mously under the system of protective tariff, of which the Republican party has been the great support. It is true that industries have been prosperous and profits large under this system, though at present, from a combina- tion of circumstances, the textile in- dustries are not so prosperous. At the same time the wages and stand- ards of living of the American work- ing man and woman have been ad- vanced under this system. Nowhere in the civilized world has labor been so amply rewarded as in the United States, and nowhere are the stand- ards of living for the workers so high as here. What will happen if the protective tariff is struck down? Wil American labor benefit by the influx of cheaper made foreign goods, textiles and other products? Will this further competition aid in opening American mills and increasing wages? Such a course, pursued by organized labor, would be cutting off the nose to spite the face. It might have its revenge on the textile manufacturers for wage re- ductions, but it is difficult to live on revenge. The profits of the manufac- turers might be made still lower, but this would scarcely increase the earn- ings of the workers. Mr. Green's threat carries back of it the potential political strensth of the American Federation of Labor. It is that political strength which he proposes to yse as a club to make the textile manufacturers “behave.” Everything, it appears, in this coun- try resolves itself finally into a po- litical question. The American Fed- eration of Labor, through its execu- tive coumcil, not long since declared that it intended to continue a course of “non-partisan political action” and to Keep away from the indorsement of any particular party. In this threat now made against the pro- tective tariff, however, the federa- tion leader is aiming directly at a Republican party principle, much to the delight of the Democrats. Probably, however, this should be considered not so much a threat at the entire principle and practice of the protective tariff as at one par- ticular industry, which has aroused the anger of the workers because of wage reductions. Perhaps labor is seeking a new weapon, and hence- forth will distinguish between “good” and “bad” industries in the matter of tarift protection. If an industry re- duces wages, then organized labor will demand that its protection be re- duced. The time may come when, if an industry fails to increase wages, the same demand will be made. The textile industry has been in difficulties in spite of its protection from the tariff, but not because of it. Prices of raw materials are high. The prices of the finished products are high. The country is practicing econ- omy, in part because it desires-to and in part because it is forced to. Men and women are making their clothes last longer. Markets abroad are curtailed. Mills in some of the { New England towns have been run- ning on part time or have been closed. If they were making great profits, it is reasonable to suppose they would be running full time. S In view of the considerate terms so gladly extended to Belgium there should be gratitude rather than envy in contemplating the fact that the U. S. A. is the richest nation on earth. A British Cricket Centurian, Jack Hobbs holds the center of the stage in England today. Not because he is a statesman or a soldier, an orator or a priter, but because he has scored his 127th “century” at cricket. He is the “Babe” Ruth of the famous English game, which means so jmuch to the Britisher and so little to the American. A ‘“century” at cricket means the scoring of a hundred runs in a single inning by the same batsman. It is staggering to the imagination of the ordinary American base ball fan. The very monotony of the repeated scor- ing would pall upon him. Imagine, for example, a base ball game in which one side scored 100 runs in an inning. The ball park would be empty long before the 50 mark was reached. Va- riety is the spice of life, particularly in America. The British take their sports more sedately than their American cousins. They hurry less. A cricket game may last for more than one day, or two days. Indeed, Hobbs broke the record previously held by W. G. Grace by making two ‘“centuries” in the same game, though on different days, He on old THE has been congratulated by pretty nearly every one who counts in Eng- land, end has even had & cable from the Prince of Wales. It seems strange that Americans have falled to take seriously Eng- land's great game, and equally strange that base ball, the national sport of America, has made no impression among the Britishers. Rowing, ten- nis, golf, polo and other sports are enjoyed equally by the Englishman and American. But when it comes to cricket, the American throws up his hands, and at the mention of base ball the Englishman looks bored. Foot ball as played in England and America 18 not the same game, but fundamentally it has similarities. The English have for centurles been prominent in sport; they have taken the time to play. They have been serious in their sport as in their-work, and sport has been a great part of thelr lives. More and more the people of America are giving time to outdoor sports, taking a leaf from the book of the English, and are becoming the happier therefrom. Whether they will ever attain an enthusiasm for ;-rlckek, however, {s exceedingly doubt- ul. ————— He Will Honor the Flag Hereafter. A Newburg, N. Y., man was arrest- ed for desecrating the American flag. He was caught cleaning his automo- bile with the national emblem, and when haled to court was given a unique and appropriate sentence. The judge ordered him to visit Washing. ton’s headquarters at Newburg once a week until Thanksgiving, and to learn the history of the flag and of the country and also Joseph Rodman Drake’s ode to “The American Flag.” This s making the “punishment fit the crime” most effectively. A man who would use the Stars and Stripes as a cleaning rag is surely in need of instruction. This offender was prob- ably thoughtless, but after a series of weekly visits to one of the historic shrines and a thorough study of pa- triotic literature, and especially the stirring poem which starts, “When freedom from her mountain height unfurled her standard to the air,” he will be more careful and more re- specttul. Respect for the flag is not a mere gesture. It is an indication of a true spirit of patriotism. While the flag is & commonplace, flying everywhere, it is none the less significant, and it should be honored at all times by all Amerlcans. There is no use in seeking to avoid recognition of the inevitable. When the Summer season is over the traffic jam will be even worse. The idea which once prevailed {n some communities of Sending a man to Congress for the rest cure should, {n all humanity, be abandoned. e e There is always something register- ing on the seismograph to prevent a fear that the world is liable to re- lapse into a state of monotonous calm. Geologists play an important part in all kinds of news from an oil scandal to an earthquake. ———— This country is credited with more criminals than any other in the world. There are degrees of crime, and the laws here are so numerous and strict that technical classification as “crim- inal” does not necessarily imply ex- treme depravity. —_— e — Realtors engaged in promoting re- sort real estate will not, for many seasons, be lured from Florida to the Arectic regions, although the North Pole could produce literature as alluring in Simmer as that of Florida is in Win- ter. ————— The record of a Summer does not appear complete unless it includes a shocking disaster to an excursion steamer. Safety first is as hard to enforce on water as on land. — e The effort of young Mr. La Follette to revive interest in Teapot Dome in the warm, weary days of August is moral and proper, but not pre- cisely strategic. . SRSV Without going deep into Darwinism, young Robert La Follette proposes to introduce an interesting study in Ro- litical heredity and environment. Any one who doubts that the world is growing better should pause and compare the modern motor bus with the old-time stage eoach. — ‘When jay walking and jay driving are both eliminated the traffic prob- lem will undoubtedly be easier. SHOOTING STARS. BY PHILANDER JOHNSON Relative Discomforts. I'm sorry for explorers bold, Who in the lands are lost, ‘Where empty distances unfold Beneath eternal frost. But when the sun above us glows, A superheated star, The tip I'd give to such as those 1s, “Boys, stay where you are!” A Matter for the Library. “What do you think of the theory of evolution?” “It's all right in its place,” said Senator Sorghum. “But it’s a mistake to try to bring a family quarrel into politics.” We All Have Much to Learn. This old world keeps us guessin’, ‘With knowledge incomplete. I've got to take a lesson In how to cross the street. Jud Tunkins says goin’ fishing is a way of making a few disappointments take the place of your cares. Large Ideas. “Would you marry a millionaire?” “No,” said Miss Cayenne: “A mil- lion these days isn’t enough to be tempting.” The Channel Dash. The swimmer faltered on the way And couldn’t make the trip. Yet, very frankly, T will say, I envy her the dip. “Dat old advice, ‘Try, try again,’” said Uncle Eben, “is what makes a, 'bed banjo player such & nuigance™ £es 2, EVENING BTAR, WASHINGTON, D. THIS AND THAT BY CHARLES E. TRACEWELL. Having considered men's clothes in general, we take up today the eternal lure of the bow tie. Few men there are but have wrestled, at some time or other, with a bow tie. It is a small but fascinating ar- ticle of wearing apparel, one that combines the charm of beauty and the snappiness of vogue with the elusiveness of the devil. Before considering the bow in de- tail, perhaps we should explain to the palpitating public that there are, in the matn, two great classes of men's tles. They are: 1. The four-in-hand. 2. The bow:, The four-in-land (also the term for four horses driven by one man) is more or less synonymous nowadays with the word cravat. This latter originally meant a Croat, an Inhabi- tant of Croatia. As applied to the ornafental piece of cloth wrapped around the male hu- man neck, the cravat got its name from a body of Austrian troops who, in 1638, adopted this form of neck- wear. France, ready then as now, to set the fashion, adopted this puffy type of neck covering. Today its suc- cessor, the ublquitous four-in-hand, divides the honors of the masculine neck with the bow, with a rather larger proportion of the honors. Perhaps three out of four men to- day wear the tle tled in a slip knot, hanging down the manly chest or stuffed in the vest in Winter. It comes in a thousand shades, the most_glaring of which are annually bought up by good wives for their good husbands at Christmas time. Yes, Santa Claus has much to an- swer for. Mok e % Before we get down to tying the bow tie, however, or attempting to, we must not forget the stock. This form of neckwear was a sort of enormous four-n-hand popular around the year 1898 and some time afterward. Look back through the photograph album and you will find any number of pompous looking boys in thelr first long trousers, their necks swathed in the layers of the stock. They wore “iron hats" (derbies) of a peculiar small size and brim, mostly had their hair parted neatly in the middle, depending thence in long waves upon the forehead, and in Winter affected raglan overcoats. The stock today is to be found only in the country districts, and not very often even there. It was a hot, un- comfortable kind of neck dress, its only appeal being that of white neatness. Right here it may be stated, once and for all, that the whole question of why men imag they must have something around their necks is shrouded in the deepest mystery. There {8 no earthly reason for neckties of any kind, Women never adopted them, and to their bare necks physicians attribute much of their freedom from colds, sore throat and even pneumonia. Men, on the other hand—or per- haps it should be written other neck —have always felt the necessity for something to hide their Adam'’s apple. It that is not the real reason for neck covering, I miss my guess. Women also possess the so-called Adam’s apple, but Nature, having been somewhat kinder to them than to men the ugly bit of cartilege with a cov- ering of fat. Her playfellows, however, have had to struggle along through life with the Adam's apple bobbing up and down at every swallow and at avery spoken word Tt was more than they could stand. So they took to the collar and tie. FACTS IN COAL BY WILLIAM ARTICLE IV. Along the road of anthracite, be- tween mine and consumer’s bin, four separate agencies take toll of every ton. Their charges for work perform- ed, plus a profit in each case, increas the price from an average of about $6 at the mine to $15 and up in the house- holder’s cellar. The Government's various investiga- tions have disclosed the four profit- taking agencies as follows: First, the mine operators them- selves, who levied a profit averaging $1.07 a ton in the first quarter of 1923. That figure covers the nine largest producers, whose output was about 70 per cent of the total Second, the middleman or whole- saler. In normal times his profit is about 25 cents a ton. During strike periods it is often much greater. 1In 1922, the Coal Commission found, it to as high as $4.75 a ton in one case, while averages of from $1 to $2.50 were not uncommon. Gouging by Wholesalers. The wholesaler's legitimate function, in normal times, is to bring buyer and seller together. In abnormal times this function is continued, but, in ad- dition, many wholesalers buy on their own accounts for as little as possible and sell for all they can get. iovernment agencies, notably the Coal €ommission and the Federal Trade Commission, found that in times of shortage and extreme demand wholesalers sold coal to other whole- salers and these in turn to still others, each wholesaler adding a profit, until some coal was burdened $3 or more per ton with several wholesalers’ prof- its. Sales from wholesaler to whole- saler occur almost + wholly, it was found, during times of shortage or strike scare. The profit in normal times of competition is insufficient to warrant division, as a rule, among several wholesalers. Third in the list of profit-takers on coal stands the raliroad. Its legitimate function is to transport the coal from mine to retailer. For this service the rate is fixed by law. The miners al- lege that present freight rates are un- reasonably high, so far as anthracite coal is concerned, but investigations in the recent past by governmental agencies have fafled to result in ac- tion to lower the rates, What the railroads make, per ton, has not been worked out. Possibly ex- pert accountants by a long and com- plicated process might be able to show average figures. However, the car- rlers transporting anthracite formerly owned their own mines, in almost every case, and the combination role of coal producer and coal distributor was immensely profitable. No Longer Own Mines. That combination has been broken up by the Federal Government; rail- road and coal companies have been divorced by the United States Su- preme Court. Undoubtedly there re- mains a sympathetic interest in mu- tual affairs between these recently severed concerns; the records show that in almost every case, due to past earnings and reserves built up out of the earnings from coal, the present anthracite-carrying roads are among the wealthiest and strongest raflroads in the United States. The fourth agency to take a profit on coal traveling from the mine to s nsumer’s cellar is the retail coal merchant. There are thousands of such firms in existence throughout the country. and the extent of their profits varies so greatly that in no two cases has it been found exactly the same. Eighty-six coal retailers in New England and 62 in the Middle Atlantic in this respect, has covered | All movements to abolish the tie since have ended in abject faflure. The “Gertie” shirt, something like the one worn by Lord Byron, proved a drug on the market after a few months. That shirt, it will be re- called, had an open, wide-spreading collar. s Revealing the Adam’s apple, failed. The main function, then, of the modern tle is to cover the Adam's apple by finishing off the modern collar. "The collar, of course, does the prime work of covering, but the necktie finishes what it begins. Bow tfes, in the main, are of two kinds: 1. The Windsor. 2. The everyday. The Windsor bow is the flowing type worn by ‘artists, and commonly called “an artist's tie.”” Just why the painters and other {llustrators should have ‘fallen” so hard for this par- ticular form of the bow is another mystery. It is undoubtedly true, however, that the average hard-headed business man would as leave appear in public in no tle at all as to wear the Windsor. He shuns it. He likes, however, does this “man in the street,” the everyday bow, as we choose to call it. As stated, one out of every four men, perhaps, wear bow tles, and the other three wear it at some time or other. The difficulty of making the four- in-hand stay up neatly in the collar opening finally drives men to the bow tle. And then their troubles begin. * Kk ox % Tying the bow tle, either for the dress suit or daily street wear, is a favorite indoor sport with some men. To watch a entleman stafd in front of the mirror, hands at neck, both elbows straight out at right angles with the shoulders, has driven many a wife into convulsions. When he begins to cuss, shortly, because the thing will not tie up ac: cording to specifications, he then drives her downstairs. The trick of tying one's own is not easily learned. Ask dad—he knows. After it is achieved, come two dif- ficult problems—one, keeping the col- lar button from showing; two, keep- ing the tie trim across. Many men have given up bow ties because they allow the gold collar button to shine forth in all its splendor. It is a distressing sight, indeed. Anchoring the bow so that it will not tiit with one end standing straight up, the other down, is an art as yet unsolved. This is one of the meanest tricks to which the bow tie s addicted With his tie “sitting pretty” straight across his neck, setting off his manly chin to perfection, a gentleman goes into the “important board meeting,” which we are all the time reading about. He has a great scheme to read, which will make a “hit" with the president, and cause the latter to appoint him general manager at an increase of 10,000 per cent in salary. At the psychological moment he it entlemen,” he begins, confident- 1y. As he progresses, however, he is aware that his big scheme is not re- celving the attention that it should. Something is the matter. He finally sits down, whereupon his plan is voted down immediately, and his prospects go a-glimmering. Leaving the board room, he hap- pens to glance into a mirror, and sees all at a glance. That darn bow tie is sitting up-and-down, instead of cross-ways! CONTROVERSY P. HELM, JR. States have been studied by the Coal Commission as typical of other re- tailers in those sections. The records disclose that in New England the net profits per ton averaged as follows during the five years ending with 1922: 6 cents cents cents 54.6 cents 58.7 cents Added by Retailers. These 86 retallers handled more than 2,000,000 tons of coal each year. The foregoing tabulation shows only their average net profits. The record shows that in order to obtain this profit they added on to the figures which each ton of coal cost them the following amounts: 1918 . 1919 . 1920 . 1921 - 1922 . In other words, for coal costing a New England retailer $13.50 per ton, freight paid, in 1922, an average of $2.94 was added for handling charges between the railroad tracks and the consumer’s bin, making ‘the average cost to the consumer $16.44 per ton. And out of that the retailer averaged 58.7 cents profit on each ton. Wide variation in mine costs of coal makes it impossible to deal in any other figures but average when at- tempts are made to measure the profits made by local coal merchants. The Coal Commission, for instance, tells of two Philadelphia dealers, both of whom sold stove coal at $14.50 per ton in November, 1922. The first deal- er, buying coal from a big producer with whom he had dealt for years, paid an average of only $9.25 for his coal, delivered. The second dealer, forced to the mercies of the speculat- ing wholesalers, actually paid $14.59 for his coal and sold it for 9 cents a ton less than it cost him, delivered. Again, two dealers in New York City, selling at $13.75 per ton, were found by the commission to be In somewhat comparable position. The first, with a good source of Supply. sold his coal for $4.51 per ton, on the average, more than it cost him deliv- ered; the second realized but $2.50 a ton more than cost. Each retailer, of course, had to meet his overhead and other expenses out of the difference between cost and selling price. Wide Variations in Profits. Throughout the year 1922 the low- est average margin—difference be- tween cost and selling price—obtained by a dealer reporting to the Coal Com- mission was 13 cents a ton; the high- est $6.05—from which it is easily de- duced that not all retailers make a profit and not all are profiteers. The 69 companies retailing €oal in the Middle Atlantic States during 1922 and reporting to the Coal Commission showed an average net profit of 39 cents a ton on nearly 6,000,000 tons handled. That was at the average rate of about 10 per cent on their investment. From 39 to 59 cents to the retailer; from 25 cents to $3 to the wholesaler; an average of $1.07 to the mine oper- ators, and an undetermined amount to the railroad companies hauling the coal—such were the actual profits, as disclosed in 1922 by the Government's research, on coal traveling its toll- barricaded way from mine to cellar. A minimum profit of perhaps $2, split four ways, a maximum running up to nearly half perhaps of the high prices demanded for the highest-priced prod- uct—these were the measures of an- thracite profits in_strike time. jstronger minds. 0., THURSDAY, AUGUST 20, 1925. RADIO IMPERILS ALL CHAUTAUQUAS By Robert T. Small. There is sad news from the prov- inces. The Grand old American Chau- tauqua, mainstay during the Summer of the indigent American statesman, is threatened. Already it has been cur- tailed, but its very life would seem to be at stake. Golden-tongued Senators and spell- binding Representatives have learned to their regret and the further deple- tion of their visible means of support that the radio is “cutting in” on the Chautauqua to such an extent that the backers of various Summer circuits are thinking of withdrawing their sup- port and yielding the field of enter- taining the plain people to the en- croachments of modern sclence. The radio, it would seem, is giving to the people precidely the line of “stuff” they used to travel miles to hear under the Chautaqua canvas. It is giving it to them at home, and it is giving it to them free, whereas in the olden times it was customary to pay out good, hard money for a series of season tickets. The automobile is another factor which_is playing hob with the grand old Chautauqua. The farmer—and every one has an auto—puts himself and his family on wheels when he has a little time to spare and goes touring the country or visiting some new El- dorado where lots are selling like hot cakes and paper fortunes are being made over night. CREE The farmer, thirsty for knowledge and shut away from the world during most of the Winter, was the backbone of the Chautauqua circults. Now that he possesses high-powered re- celving sets and all manner of trans- portation from the lowly flivver to the imported Rolls Royce, the Chautau- qua has lost much of its appeal. Many Chautauqua orators, accus: tomed to having long Summers of Chautauqua work, found themselves out of a job this season, because of the curtailment of circuits and pro- grams. In most instances the radio encroachment was given as an ex- cuse to the disappointed spellbinders, who had carefully prepared new and devious ways of making the eagle scream and of twisting the lion’s tall, to the delight of the rural populace. The farmer this Summer is either on tour when he can get away from the crops, or is sitting home evenings tuning-in on programs far more varied than the Chautauqua in his vicinity was able to offer.. Over the ether he can get his polities, his scien- tific lectures, his daily or weekly planations of the situation at ‘Wash- ington and throughout the world His advice from the Department of Africulture, both State and Federal: his concerts, his base ball scores and just about all in the amusement or the educational lines that his heart desires. The farmer finds also that his daily paper brings him far more informa. tion and entertainment than it did in the old days when the Chautauqua first began to flourish, so that alto- gether he can lead a very comfortable and contented life at home % x % The same conditions apply to the residents of tfe small villages and towns. They also used to flock to the Chautauqua tents, but are being weaned away from the old style of entertainment. They can hear their Swiss bell ringers now over the radio; they can listen in to the sextet from “Lucia” or the quartet from “Rigo- letto” and hear better artists than it was possible in the older days to in- duce to go on the Chautauqua plat- form. The dear old statesmen are the ones hardest hit by the radio defections from the Chautaugua. Perhaps that is why so many of them have braved the Summer in Washington this year. Perhaps that is why also there is an embargo on the radio in Congress. Undoubtedly the Chautauqua is in peril and the question is “who will save it?” ———— Better Health Education Required by Children itor of The The Star is certainly to be con gratulated for bringing to the atten- tion of the public the real condition of affairs regarding_ playgrounds —and juvenile crime. In my opinion, the Whole trouble lies in the structure of physical education itself. Not that in- structors are in any way at fault; but the general system appears to be weak when results are carefully scru- tinized. In fact, these results look about as bad as those which were dis- closed for grown-up men at the time of the call to the colors during the World War. I would go further and say that the present system of physical education is fundamentally wrong, in so far as the span of each Individual life is con- cerned. Boys and girls are taught a great amount of things iwhich have a certain value for youth in the field of _athletics. Having had under my care dancers, acrobats, wrestlers, welght.lifters, etc., I am in a good position to know after 18 vears' experience. But the simpler things which those same boys and girls should know for the fight for health in more advanced years are thoroughly neglected. The ‘excuse is that it will be time enough later for the adult to learn how to ward off disease through the proper care of the marvelous machine which is our body. “Errare humanum est.” How much simpler would it be to teach youth what youth will have to do later along the aforesaid lines. In this manner outh would learn sooner the real value of the body, and this would un- doubtedly be of great value to those who are unfortunately inclined toward bad tendencies. A real comprehension of the body means clearer and Let boys and girls at large know that some of the best acrobats and dancers in the world have developed most of their talent with the use of a simple chair. Let them know more, also, that the Greek athlete, questioned about his marvel- ous strength and agllity, answered: I am strong because 1 am chaste. HENRY L. BURR. Proposed Weight Tax On Automobiles To the Editor of The Star: On the first page of Tuesday’s Star appears a story, ostensibly inspired by the office of the tax assessor, which proposes a new schedule for personal tax on automobiles. Recently this office bewailed the many evasions of personal taxes on autos and proposed that this tax be levied when tags are purchased. Now they come forward with something different and entiredy vicious. This new schedule to take the place of the present tax on valuation is to be a weight tax, graduated upward, and, to quote your story, “In explain- ing the proposal now being considered these officlals say that a car four or five vears old gets as much use out of highways as a new car.” Of course, as a taxpayer I am probably wrong, not to say ignorant, but will you hazard an opinion as to when the object of the personal tax was to maintain highways? Does not the gas tax attempt to collect for the use of highways? Or do these officials feel they should make us pay twice for using their highways? If they get away with this will it not also be reasonable to expect them to make us pay a heavier tax for a brick house than a frame, because the brick house puts more weight on the landscape? ® FRED 8. WALKER, ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS BY FREDERIC J. HASKIN. Q. How does the silencer on a rifle work?—E. M. P. A. The National Rifle Association says that a silencer works on the same principle as an auto muffler. The tube is screwed on the muzzle of the gun. This tube consists of series of baffles that cause -the gases to issue slowly instead of with a sudden rush. It is this rush of powder gas from the muzzle of the gun which creates a vacuum causing the report when dis- charged. Q. Wil hard city water that has been manufactured into ice become soft in the process?—E. A. R. A. The Bureau of Standards says that as the water freezes the crystals formed are nearly pure water, the dis- solved impurities that make it hard remaining in the unfrozen part. Even sea ice is nearly fresh. Q. What was the name of Blue- beard's wife?—G. B. A. Her name was Fatima and her sister’s was Anne. Q. Is it true that people who live on farms have more children than those who live in towns and cities?—N. F. P. A. The farm population of the Na- tion, although less than 30 per cent of the total, includes more than 35 per cent of the child popuilation. Q. How often does the word ‘re- Jjoice” occur in the Bible?—A. M. W. A. It occurs about 177 times in the authorized version of the Bile. Q. —What were the important cam- palgns of the Revolutionary War?— J. C. A. The most important were: Cam- paign of 1776 (Long Island and Fort Washington), campaign of 1777 (Sara- toga), Lafayette's campaign in Vir- ginia, April, 1781-October 19, 1781. Q. How high does the Ganges rise in the rainy season?—A. N. ummer the river rises e the normal level at the beginning of the delta. The flat coun- try of Bengal is inundated to the width of 100 miles. Q. What was the name of the poi- son used by the Aztecs for their ar- row heads?—J. W. 8. A. The Smithsonian Institution says that the South American curare (and other native names) poison for arrows concocted from stryshnos nux-vomica did not extend to Mexico. There is little relfable information on what poison, if any, was used by the Aztecs and other Mexicans on arrows. One reference says that arrows were dip- ped in the acrid juice of leaf of an agave, but the species is not given. The Aztecs were adepts in the prop erties of plants, and aside from the wound, could have made an arrow very disagreeable Q. Was Ford's Theater ever used fter Lincoln’s assassina- H. A. A theatrical performance was never given there after the tragedy. Q. Will you suggest a few books I should read in studying English literature?—F. C. by Swift; “Tom Jones,” by Flelding; “She Stoops to Conquer,” by GCold- smith; the poems of Robert Burns; “Pickwick _Papers,’ by Dickens: “Heroes and Hero Worship,” by Car lyle; “Vanity Fair,” by Thackera: “Ordeal of Richard Feverel,” by Mere dith; “Tess of the D'Urbervilles,” by Hardy; “The Forsyte Saga,” by Gals- worthy, and the letters of Robert Louls Stevenson. Q. How many miles of railroad are there in China?—L. B. A. There are 6,818 miles of rail ways in China, according to last year's report, and nearly 2,000 miles in Manchuria. Q. What fs “thieves Latin?"—W. §. A. The word “slang” is the modern equivalent of the term. Until the nineteenth century it depoted the Jargon peculiar to thieves or vagrants. Q. Is it true that there is a law in Peru requiring foreign firms doing business there to keep their books in the Spanish language?—O. T. A. Peru has such a law, effective last’ January, making it compulsory for all organizations and individuals engaged in commerce or industry in that country to keep their account books in Spanish. Books not so kept will have no value in court and, in addition, a heavy fine may be im- posed upon violators of the law. Q. When was the Folk expose in St. Louis?—A. M. R. A. Joseph W. Folk was circuit at torney in St. Louls, 1900-1904, and it was during that period that he made the fight on political and official cor- ruption and prosecuted the bribery cases that attracted nation-wide at- tention. Q. Of what nationality is Bucky Harris?—H. W. A. Stanley Harris is an American. On his father’s side, he is of Welsh descent, on his mother’s, Swiss. Q. What street in the United States has the most traffic’—A. H. A. Michigan avenue, Chicago, is now sald to have the heaviest traffic In 24 hours, the count was 66,000 ve- hicles. Park avenue, New York City was second with 40,560 vehicles, and Fifth avenue, New York City, was third with 39,000. Q. Why do crabs turn red when dropped in boiling water?—J. M. A. It is due to & chemical change. Q. Is the game of cards spelled ““casino” or “‘cassino”?—C. C. A. The proper spelling of the word 1s” “‘cassino.” (Letters are going every minute from our free Information Bureau in Washington telling readers whatever they want to know. They are in answer to all kinds of queries—on ail kinds of subjects from all kinds of people. Make use of this free service which The Star is maintaining for vou. Its only purpose is to help you, | and we want you to bemeAt from it. Get the habit of writing to The Star A. The American Library Associa- tion recommends “Gulliver's Travels,” There seems to be fear that Chinese extraterritoriality is about to be aban- doned, and alien residents are reported as somewhat nervous as to what will become of their safety and property rights, when they have no defense or justice except what may be gotten from Chinese courts Even with the present safeguard of foreign courts established by treaty to protect the nationals of the several countries having diplomatic relations with China, the thousands of strikers in the textile mills owned by the Japanese and British have boycotted practically all forelgners except the Americans. When the strike became tense, @ crowd of strikers undertook to invade the foreign quarter Shanghal. The mob was held back by British soldlers or police, who opened fire upon the Chinese. Im- mediately the diplomatic body Peking appointed a commission to make impartial inquiry into the affair, and the Chinese government appoint- ed a commission to join in that in- |quiry. The findings of the joint inquiry were kept secret. It is said to have leaked out in France that the verdict is adverse to the British. I1f that verdict becomes known to the Chinese mob,. further disturbances and further demands for expulsion of all foreigners, and aboli- tion of all extraterritoral courts for protecting foreigngrs are likely to result. * x % The United States has a long record of unbroken friendliness toward the Chinese. Many Americans have the misconception that our Government has exercised ultra-altruistic methods in dealing with China, such as it would not allow in dealings with more powerful or enlightened nations. We have a record of having pro- tected Chinese rights, notably In Secretary John Hay’'s demand of the nations that they recognize in China jthe “open door” wherein all nations would be on an equal footing in Chinese trade. Americans have proudly boasted of the supposed altruism manifested when our Government gave back to China the indemnity received for the damages of ther Boxer Rebellion. The story is simple, yet much misunder- stood by the public, according to one of the high officials of our State De- partment. The nations in 1900 had marched with their allied armies to the re- lief of their legations at Peking. Later they presented claims of their respective nationals who had been damaged by the insurrectign. These claims were demanded in one sum, and the dues to each nation were divided by the united allied nations. The private claims of Americans to- taled about $3,000,000. The military expedition of rellef cost us about $6,000,000. Our Treasury was author- ized by Congress to reimburse the private claimants without waiting for the collection from China. It was agreed that China should amor- tize her entire debt, annually, pay- ing part on the principal and part on the interest. The payments be- gan in 1902. By 1908 it was seen that the amount which China had agreed to pay us would exceed all that she had cost us in the Boxer Rebellion. President Roosevelt di- rected, therefore, that China should be notified that we would rebate the excess. This was partly done then; more has been rebated later—not as a matter of generosity, but of honest settlement. The broadness of the settlement— the example in international honesty —was received by China as a magnifi- cent lesson. Her diplomats suggest- ed that the Chinese government de- sired to commemorate the deed in some suitable way and asked for suggestions. The idea that the re- bate might be set aside as a fund for the education of Chinese In ‘Western learning and ideals was ac- cepted and put into action. The initial suggestion as to the use of the fund, however, was not a “con- dition precedent” to our rebate; it came only as an afterthought from an appreciative China—commemorat- ing the act and crystallizing the 'adage, “Honesty, is the best policy,” of | Information Bureau, Frederic J. Has- kin, director, Washington, D. C.) BACKGROUND OF EVENTS BY PAUL V. COLLINS. whether relations. It was vastly more telling than an act of mere sentimental generosity, which, in the light of age-long Chi- nese thought of her superiority over the rest of the nations, might easily have been construed as a subtle trib- ute to her greatness, by a pation Tearing her ultimate wrath. When our Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, gave his instructions to our first Minister to China, about the year 1840, he directed that spe- cial emphasis be put upon our re- fusal to pay tribute to the Chinese Emperor—as had been the custom of many Asiatic .nations for centuries. * X X X Extraterritoriality in China was ao- corded in 1844, in our first treaty with* | that country. It has since been given to other treaty powers, so that now the Chinese protest against a great in private or international at| multiplicity of courts which compli- | cate not only proceedings in which a foreigner and a Chinaman may be theditigants, but cases where two for eigners, from different countrier, | each claim protection, not acefrding | to Chinese laws, but according to the | conflicting laws of the foreign coun- tries. The question as to which set of laws should apply in such a case depends upon which national sued first. There is no immediate certainty that the treaty nations will agree to the abolition of the right of trving their nationals before their own courts, al- though that abolition was urged at the Washington disarmament confer- ence of 1922, and seeming encourage- ment_was_given to China in resolu tion No. 5, which, however, merely promised that the nations would ap- point a commission to consider when and how the extraterritoriality courts might be safely abolished. That com mission, making no promises of under- taking the abolition desired, will meet in October to consider the situation; it has not met heretofore, because it had no powers until all the treaty nations had signed and accepted the conclusions of the conference; France signed only a few weeks ag By the resolution at the conference, as stipulated: ‘That China, having taken note of the resolutions affecting the estab lishment of a commission to inves gate and report upon extraterritorial- ity and the administration of justice in China, expresses its satisfaction with the sympathetic disposition of the powers hereinbefore named in regard to the aspiration of the Chinese government to secure the abolition of extraterritoriality in China, and declares its intention to appoint a representative who shall have the right to sit as a member of said commission, it being understood that China shall be deemed free to accept or reject any or all of the recommendations of the commission. “Furthermore, China is prepared to co-operate in the work of this com mission and to afford it every possible facility for the successful accomplish ment of its tasks. “Adopted by the conference on the limitation of armament at the fourth plenary session, December 10, 1921." The Chinese ideals of courts and of law are widely different from our own There is no demarcation between statutory law and the discretionary power of a judge to make his own laws to fit the case before him, o long as he rules along lines of ‘“rea sonableness"—at his own definition as to what that means. In the eighteenth century Emperor Kang Hsl issued a decree urging and commanding the people to avoid ap. peal to the courts, but to submit all disputes to arbitration for compromise settlement, and he added: “I desire therefore that those who have recourse to the courts ve treated without any pity, and in such a man- ner that they shall be disgusted with law, and tremble to appear before the judges. In this manner the evil will be cut up by the roots; the good citizens who may have' difficulties amongst themselves will settle them like brothers by referring them to arbi- tration. As for those who are trouble- some, obstinate and quarrelsome, let them be ruined in the law courts— that is the justice that is due them.”