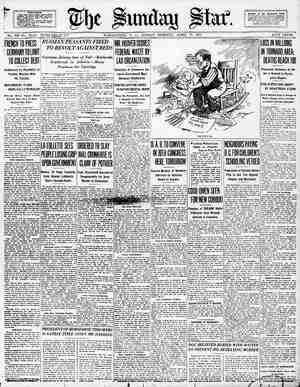

Evening Star Newspaper, April 17, 1921, Page 66

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

[ THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C, APRIL 17, 192]—PART 4 THE RAMBLER WRITES OF GHOSTS OF TODAY AND OF DAYS LONG GONE BY On a Trip to Rippon Lodge He Stops Among the Oaks and Interviews a Specter. And the Ghastly Per- son Tells Him a Few Things of the Long Ago—The Famous| Ghosts of History and Their Peculiar Antics, Accorc]ing to Famous Woriters. EN and women have no greater consolation than they find in ancestors. One reason is that ancestors are nearly al dead and cannot come to make a visit except in spiritual form, and in that form it costs very little to feed them, and the cold. material eves of the neigh- a bors do not see them. Therefore, the | neighbors are not apt to make any com- | ments on the cut of their clothes, their | table manners and their way of speak- ing. Ancestors invisible and intangible ' are an asset to anybody. There is an- | _other advantage in having ancestors. ! They cannot defend themselves against | the grossest and kindest misrepresenta- | tion. They can always be spoken of as ! the largest landholders and the largest slaveholders in Cockleburr county. ~An | ancestor can_always be spoken of as one of the richest men of his time. A jovial, pleasant old_ spirit who is now sitting on the edge of the Rambler's ink bottle—ink bottle, that's all—whis- | pers to him that many rich people in | the good oid days were as hard and| mercenary in_their thoughts and had ! just as many bristles on them as a great | many wealthy men and women do to- day. It seems to be the right and pre-, rogative of all ancestors to be. or to! have been, rich, distinguished, honored and accomplished. There were no poor and the poorhouse or poorfarm records and the poor-house or poor-farm records are all at fault, because they show that a great many men and women, Who must have been ancestors, really had as | hard time to get along as you do to pay | your gasoline bill and keep up vain ap- pearances. * X ¥ ¥ ANCESTORS were always distin- guished. My old friend, the spirit who sat on the edge of my ink bot- tle, laughed so merrily as I wrote that line that he fell in and I have just dropped the cork to him as a life preserver. Ancestors were al- ‘ways justices of something or other, member of the council. on thé stafl of the governor, sheriff of the coun- ty, the king’s high jailer, or a colonel in the state militia. Well, we have all these kinds of men today, and to some of them we do not attach un- due importance. We know that “Honest Sam,” a member of the leg- islature from Skunk Wallow, is a crook, and that Col. Four Fiush Fal- staff of the governor's staff never smelled any stronger powder than talcum. But two hundred years from now, as ancestors, they will be a mouthful! Their portraits will hang in the parior and a sweet little aristocratic lady, when she opens the door to visitors, will say, “Welcome to the hall of my ancestor: Or it may be that her husband is the member of the family in whose pale blue veins flows the proud blood. Per- haps two hundred years from now, when some reporter asks him if it is true that he gave an N. G. check for his board bill, or when a bill collector asks him to come across, the little man may puff himself up to the explosion point and say, “Sir! How dare you! You do not know to whom you speak! Let me tell you, sir, that I am a descendant of the Hon. Honest Sam of Skunk Wallow and of Col. Four Flush Falstaff, who served on thé governor's staff.” The little old spirit perched on the ink bottle puts another idea in the Rambler's head. It is this. If an- cestors could have known how much distinction—nay, almost giory—would be conferred on their descendants by buying a piece of wild land at two ehillings per acre, they would have bid the price of that land up. To be descended from Nicholas Tightwad, “the patentee or original grantee” of the tract of land called inaquapin Thicket, or Briar le, is an homor ‘which sets a man far above that bit of common clay. named Themas Grub- ber, who bought Chinquapin Thicket from “the original grantce,” paying him 3 profit on his speculation, chop- ping down the trees, building him- a one-room log cabin and work- ing at the praiseworthy job of raising corn and tobacco. Many of the “original proprietors” took up land at two shillings the acre, not to live on it and make it bloom and bear fruit. but to hold it for sale at a higher figure to some landless man who felt within him the home- making urge. For ancestral purposes Nicholas Tightwad is much more or- mamental than Tom Grubber, but somehow the Rambler feels that if he were walking through that coun- try 250 years xgo the sweet face of old Tom’s daughter, Sallie Grubber, ‘would make a stronger appeal to him than Miss Clarice Tightwad. in the parlor of her home on the main street of St. Mary's City or on the Duke of Gloucester street, or Boutetout street, or Queen street or Palace street in Willlamsburz. But enough of idle thoughts along that line! Most men insist on measuring the importance of ancestors by the lands and of-| fices they held. It is an unreasonable standard. Millions of ancestors, with- out land and who never held a public office—dog-catcher. coroner or sena- tor—were worthy people when meas- ured by the great and just standard which may be expressed as “charac- ter” It is so today. Suppose we should assume that the worthiest persons now are the rich and those ‘Who scheme and plot for public office? % % % T“ Rambler has in mind to tell & story about a very old house on the road. or rather off the road, between Occoquan and Dumfries, and ‘where dwelt plain people, pious, un- ostentatious people, In comfortable eircumstances, brought about by their own industry and thrift. Many de- scendants of these people are living im Virginia. Kentucky and other parts of the world, and if they are good as these ancestors of whom the Rambler mmeans to write, he would be willing to take a long walk with them and eat lunch in the woods. These are tests and trials of compatibility. But before the Rambler gets to Rippon md‘z. the little old spirit on the ink bottle grins at him and reminds him that once upon a time he promised to tell his readers a certain ghost story. Some of you emile at ghosts—and run away from them—but the Rambler has seen many ghosts. He has seen some of them on the stage, for it would seem that many ghosts have theatrical talent. The most persistent and celebrated of these, as well as the most talka- tive, was the ghost of Hamlet's father, royal Dane, who burst his eerements to revisit the glimpses of the moon. You have scen the ghost of Banquo. You have seen him sit in Macbeth’'s place at table and have seen him come and go. Macbeth saw would not sleep well in the Tower of London, but would be disturbed by Un- cle Clarence’s “angry ghost.” There are equally authentic references to ghosts in “Measure for Measure,” “Winter's Tale” the “Henrys." omeo and Juliet” ‘“Lear” and ymbeline.” You know of a great many ghosts books—fiterary ghosts, as it were. Marley's ghost has frightened you into giving up a dollar at Christmas, and in the case of some of you that is proof of the tremendous power of a ghost. You are also aware that there are many haunted houses in Virginia and Mary- land, and you could hardly belleve that ‘a house could be properly haunt- ed without ghosts? Ghosts, perhaps, are just as well established as many other things you consider as facts. The Rambler is not_saying this in defense of ghosts. He feels that ghosts are well equipped to defend themselves. Hamlet knew that ghosts could be dangerous if they had a mind to, and he followed his father's ghost because it beckoned him and “waves me forth again.” and because he did not set his life at a pin’s fee, “And for my soul what can it do to that, being a thing immortal as itself™ Horatio had a pretty clear estimate of the danger of the ghost, and warned Hamlet that it might tempt him toward the flood “or the dreadful summit of the cliff, that beetles o'er his base into the sea.” He thought that there the ghost might “assume some other horrible form. which might deprive your sov- ereignty of reason and draw you into madness.” But the particular ghost story which the little old spirit on the ink bottle urges the Rambler to tell fol- lows: The day was not far spent, but the shadows of the oaks made the ceme- tery dim. The Rambler put away the notes he had been making and moving off to another part of the great and beautiful burying ground he sat down on a flat tombstone to rest. He observed, as everybody else has observed, that some graves are carefully tended and others not; that some have costly monuments, others simple markers, and that at some graves no epitaph tells who_sleeps below. He called to mind that verse of Horace’s ode to Lucius Sestius, which runs: Death, with fmpartial foot, Knocks at the hut, The lowly As_the most princely gate. O favored friend, on life’s brief date To count were folly: Soon shall, in vapors dark. Quenclied be thy vital spark. And thou, a silent ghost, for Fluto’s land Embark. Then he fell to musing on whether there is equality in death or after death. A little way off was a ragged green box-brush, about which grew tall, rank grass. In the shabby green- ery there appeared to be a form that was not shapen like a gray tomb. It had the outlines of a woman. The Rambler lighted his pipe, and as the thin blue smoke rose among the oaks this is what he thought he saw and heard: * % % % THE form that was not shapen lfke a gray tomb came toward him. It was a woman. She had rather a haughty air, as so many women have. Her bones were old and yellow, and they rattled as she walked. No doubt she had been a beautiful woman, “yet to this favor shall she come at last!" Her dress, which seemed once to have been of cream-colored satin, was now nearly as gray as the gown of a Quakeress, and stained with rust. The skirt was full, with big, wide flounces from the hem to the hips. You can see skirts like it in old pictures and in the National Museum. The slceves were long, with much puffing at the shoulders. and the bodice or basque was low cut, showing the yellow ribs of the wearer. As she came near #he raised the bony fingers of one hand to her eyeless sockets as though adjusting a_lorgnette, and looked calmly at the Rambler. Elsewhere than in a graveyard this specter would have seemed fearsome, but it harmonized so with the shadowy oaks. the dim light and the irregu- lar ranks of tombstones that it flitted perfectly into the scene. The Ram- dler spoke to her. But being some- t at a loss just what to =ay. he suppose you are acquainted with the good woman whose tomb is here™* She liked not the question. She gave rather a disdainful toss of her bare skull, and in a voice, well mod- ulated, but still having in it some tones like the creaking of a rusty hinge on a vault door, xhe said: “I know the lady you refer to, but she is not a speaking acquaintance of mine! We live in different neigh- borhoods in this cemetery. Our fam- ilies belong to different sets.” “Julius Caesar! Madame!" ex- claimed the Rambler, “and does that make a difference even among ghosts?” “Well,” said the specter, “one should not expect persons of different spheres in life to be pae- ticularly neighborly ~just because they happen to be dead. The lady you speak of, I think, lived up in the brickyard section where Dupont Circle is now, or out in the suburbs where Sheridan Circle is, before she came here, while my family lived on Indiana avenue! At one of the moon- light receptions which I hold at my lot on Tuesdays I have heard it whispered that the lady. at one time, did her own housework!” ~As the specter said this its bones seemed to shudder, but the skeleton in the dress that had been cream-colored satin, continued: “I have also heard that her par- him, too. You know that Brutus told | ents were engaged in trade; that her Veolumnius that the ghost of Caesar|father ran a merchant mill on Rock appeared to me two several times by night: at Sardis once. and this st night here Nagk #old Gloucester that he (York) creek, Cabin John or Pimmitt run; that her grandfather was a toll- in Philippl's | gate keeper on the Marlboro pike, that her great-grandfather at an one time had something to do with it was! AN OLD PRINCE WILLIAM ROAD. % ) a tavern on the Leesburg turnpike somewhere between Difficult run and Sugarland, or it may have been be- tween Sugarland run and Goose creek. 1 have also heard that her husband was engaged in real estate, or journalism or some such humble calling. The lady sometimes takes the air along this pebble path at midnight when the moon is shining. and I positively believe she makes her own shrouds: at least they look homemade. 1 am sure she never thinks of going to a fashionable shroud-modiste! There is not the least style about her. There is never anything exclusive in them. Why, down there by the mortuary chapel, where many of the middle-class spirits walk on Satur- day night. every third woman will have the same kind of hat on! And she never goes away in summe; You must not leave here, Mr. Ram- And her hat bler, with the impression that one ‘xin‘u- associate with everybody who es!” * * x % ABOUT this time the Rambler's pipe went out, the cold ashes fell upon the tombstone on which he was resting, and a couple of grave- diggers, one telling a merry story which made the other laugh, came along the pebble path. All these things reminded the Rambler that he has made a wide digression, and very little progression. or, at least, a slow start, in getting down to the story of Rippon Lodge, on the road to Dumfries. There Col. Richard Blackburn, who came to the colony of Virginia from Rippon, in England, was laid at rest under a great flat stone July 15. 1757, in the fifty-sec- ond vear of his age. Beside him, under another large flat stone. which never was inscribed, rests all that is mortal of his wife, who was a daughter of Rev. James Scott and his which was the first to come into possession of a tract of land in Fair- fax county, through which the road from Langley to Vienna runs now, picturesque stream which many of us_call Scotts run. There at Rippon Lodge died Ber- nard Hooe, mortally Maj. Kemp in a duel that was fought across the Potomac in Maryland, by the side of Mattawoman creek. There who came from Clifton, Atkinson, England, who be- Nottinghamshire, died there January 30, 1844. There stands a fine specimen of the Ken- forest trees in our woods. There to- day iives Thomas Marron, grandfather was an assistant post- master general In Washington sixty years ago. and who himself was long identified with the District Na- tional Guard. Many of you will recall Tom Ma. . who was on Col. May' as quartermaster of the old 1st Regi: ment, and who organized old Bat- tery A. That is, Tom Marron was living at Rippon Lodge when the Wambier strolled in there, before winter set in_and before the Ram- bler began his Analostan Island travels. The Rambler did not know who lived at Rippon Lodge—in fact. he did not know it was Rippon Lodge—when he entered that old estate late last fall, and the narra- tive of which he put aside until he got Analostan Island off his chest. But. of Rippon Lodge anon! ' THE BLACKMAILER | By Frederic Boutet Transiated From the Fremch by WILLIAM L. McPHERSON. 6 ONSIEUR, there is a gen- tieman outside who says he is an agent of some philanthropical society in Paris.” “Show him in," said M. Blestat, fold- Ing up his newspaper. The servant ushered in a tall, thin personage, unkempt and seedy look- ing. “Monsieur, T am honored,” began the visitor, taking a seat to which M. Blesat beckoned him. “It is a charm- ing house you have here—one of the best in the city.’ “Will you kindly let me know the object of your call?” M. Blestat in- terrupted. “I shall do so with pleasure. You are M. Theodor Blestate, merchant, widower, fifty-five years of age, fath- er of a'young man of twenty-eight, M. Phillippe. Don’t be impatient. You will s0on understand everything. We shall dismiss the philanthropic socie- ty. That was only a means of getting in to see you. I came for another pur- pose. Your son, my dear monsieur, is engaged to Mile. Claire Verralive. The ongagement dinner has already taken place. A good alliance—a very ®o0d alliance. A beautiful girl, with a fortune influential relatives and high social standing. M. Verralive is a man of the old school, upright, con- scientious, honorable, thoroughly i His life is as clear as a crystal M. Blestat was a little bored. “I know M. Veralive's good qualities as well as anybody.” “Then, my dear monsieur, what would he think of your brother Au- guste?” )M, BLESTAT almost jumped from * his seat. His face grew livid. “My dear monsieur, merely to ses you at this moment would end all doubts,” observed the visitor, with infinite satisfaction. “The proposition which I am mak- ing here,” he resumed, “is somewhat delicate.” But my aim I8 to avoid in your interest the circulation of an- noying gossip. You will note, also, that I am only an intermediary. The people who send me don't live here. They live in Paris. Well, they have known your brother. They know— yes, yes, they know everything. His escapades at Nantes and in Paris and, then, the grand climax at Bor- deaux—his trial and his conviction. That's long ago—twenty years, at least. And he died down there, poor Auguste, before his prison term was up. Yes, one might think that it had all been forgotten! But there are people who remember it, and they chose this moment to send me here to say to you: ‘Monsier Bles- tat, does M. Verralive know that your brother was in jail? Have you told him so? “That is the first point. Now, if M. Verralive did know, would he allow his daughter to marry your son? That is the second point. My dear monsieur, I realize that this fs embarrassing for you You You have lived Your son is an ** %% very are honesty itself. a blameless life. exceptional young man. There no question about that. But we are business men, discussing a bu: ness proposal. You see what I am coming to, don't you? Now, don't take the trouble to argue about it. The truth is written in your face, Any one looking at you now could read it. So the third and last ques. tion is: ‘How much will you offer u: to suppress t scandal?” Quote your figure and I will quote mine.” There was a long silence. “Who are you?" asked M. Blestat. “I was a witness at poor Auguste's trial. We had been friends. He had spoken of you several times. Rightly | or wrongly, he thought that you had left him in the lurch. and he held that against you. It is self-understood that when one has an honorable repu- tation, he doesn't want to compromise it. But a brother is a brother, in spite of everything! Yes, I know that you had a son and wanted to keep all this hidden from him. And poor Auguste had so little self-control. He was a flighty person, like myself. You are perfectly normal, monsieur. So much the better for you. In short, having been recently in strait- ened circumstances, I thought of you. By accident I learned that you were a prominent merchant here. friends gave me their advice. formed a little association, as, were, to exploit my idea. They fur- nished me the money to come here. So I came and made Inquiries, It was lucky I arrived just before your son's marriage. That made things easier. * e e “I SEE, however, that you don't sh to name your own price. I will tAll you ours—a hundred thou- sand flancs. It's a good figure, but not big enough to hurt you. No; please don't try to discuss it with me. Think it over. I'll come back to see you tomor: You will tell me yes or no. 1If it's no, I'll go to M. Verr. live and tell him poor August story. He may pay me something for my trouble. Then I'll spread the news about the city. I believe it will be yes, TIl collect and take the next train. Everybody will be satisfled. The marriage wiil take place and you will never hear of me again. “My dear monsieur, 1 give you my word of honor,” he concluded with what he wanted to be taken as a pledge of absolute good faith. He bowed confidently and went away. The garden gate slammed behind him. M. Blestat remained seated in his chair, still holding his burnt-out ef, ette in his fingers. He was dumfounded. He knew even better than his impudent visitor what would be the effect of such a revelation and what obloquy, unjust but inevitable, would fall on him. He thought of his friends and of his oriemies, of the rich, prudish and straight-laced sccrety of that little provincial city, where everybody knew everybody else. He thought of M. Verralive. the undisputed head of that society, a family alliance with whom he been so proud of establishing. He thought of his son. Philippe, who adored Claire Ver- ralive. Through all his thoughts the shadow of the black sheep criminal stalked menacingly, and that other shadow of the blackmailer, who had just departed, whose demands, if he once ylelded to them, would undoubt- edly be renewed again and again. M. Bleptat refiected for long tima. ' He came to one decision and then another. Finally he made up his mind. He got up and put on h hat, n he hesi- tated. Then he left the housa. Fifteen minutes later he was in the presence of M. Verralive. The latter, highly imposing in appear- ance, with long gray hair and a noble face, wearing a fixed, grave smile, listened as he leaned against the mantelpiece in his private office. M. Blestat had come to tell the truth. He told it. He outlined briefly his brother's history—his extrava- gances, his misfortunes, his miscon- duct. his condemnation end his death in prison. Then he told of the visit he had received and the attempted blackmail. He spoke with a dead voice, and shame almost choked him. * % %% M. VERRALIVE had listened calm- ly. He spoke after a pause of several minutes. “Why didn't you give him the hun- dred thousand francs”™ he asked. “I have told you—because he would have continued to threaten me be- cause it would have been a menace constantly hanging over me end my son. Also, because I realized that 1 was wrong in concealing all this from ou.” y"‘i‘l wasn’'t because of the amount he asked? the amount didn't matter. 1 given three times as much to—" He didn’t complete the avold the humiliation 1 sul moment.” “It i3 easy to see that you are rich,” sald M. Verralive. “My dear monsieéur, you were right to refuse. One oughtn’t to allow himself to be squeezed that way. I don't deny that this affair is embarrassing. But have a high ra,nrd for you and your son. Neither of you is to be blamed. ‘When this blackmaller comes back to- morrow show him the door and threaten to call the lice. If he dares to come here I'll take care of him. We won't allow him to spread any scandal in this town. Moreover, who would belleve him if I, Hippolyte 1‘;ermllve. publicly branded him as a ar? M. Blestat breathed freel; He was filled with gratitude. “I thank you from the bottom of my heart,” he aald. “Not at all, not at all” replied M. Verralive, magnanimously. n't mention it again. So the marriage will take place next month. By the way, I have also something to tell you. We are men of affairs; I can talk frankly with you. It concerns Claire’s dot. Owing to circumstances hrase, “to er at this which I hadn’t foreseen, I find I don’t want to see the children suffer on that account. 80 I have counted on you to give it in my stead. It's no 8"“ matter—not to you, at least. nly a hundred thousand francs. There is no reason why you can't ac- commodate me, is thers?’ he conclud- ?‘h‘xn & tone which brooked no re- usal. “None at all—none at all* stam. mered M. Blestat, ing In fore Ing a smile, in spite of his profound astonishment. wife, Sarah Brown, a family [than reasons of bereavement, came owner of Rippon Lodge, and|string girdle casually confined fucky coffee tree, & tree of very wide |or beige and distribution, but one of the rarest|Women dressed in this fashion passed WILL AMERICAN WOMEN ADOPT BLACK , CLOTHES SPONSORED BY THE FRENCH' Paris Dressmakers Es- tablished the Fashion During War for Rea- sons Of Economy. anc] There Was a COI’I-| certed Effort Among French Women to Standardize Their Ap- parel—and Black Re- mains a Favorite. BY ANNE RITTENHOUSE. HFE fashion for black grows Serious. It was established by France during the war for reasons of economy rather and there was a concerted plan among French women to standardize their apparel. so the American thought. and through which land flows that|For a year before the armistice, and ever since, found the visitor women in mass to France wearing wounded by |clothes reduced to the elements of simplicity. The frock itself was noth- ing but a chemise without sleeves, sleeps under the tombstone George | without collar. It was not any longer than the garment with which we closely associate the name chemise. A the loose frock at the hip line. The hat was black, the stockings were gray the slippers black. before the eye from Bordeaux to Bou- whose | logne with the monotonv of a frieze. When gayety replaced grief the 1f it's yes. and ! 1]oft dead bla UK. CREPE DE CHINE, V fer the rejuvenated tailored suit for the street. She will rarely get this in black. Strange that the fashion should have skipped this one costume. The average woman would choose black for her suit quicker than she would for her frock. This season that choice must be reversed. Dark blue jcomes back into fashion through the jmedium of the coat and skirt, but covert cloth and beige flannel and other colors and fabrics with the same lack of originality are offered for the new spring coats and skirts. And with them there is a return to the white wash blouse. As fashion still insists upon coats being kept on and not removed in public, the blouse may dwindle down t3 a vest and col- lar’ of white organdie or handker- chief linen. Lace is rarely used. Net appears to have vanished from the costumes of the mannequin who wore the tailored suit showing us all how the thing should be well done. The sweater blouse is not worn nor the colored silk nor jersey blouse unless the costume is in three pieces. In that case it is the intention of the wearer to remove the coat in the house and appear with a blouse and skirt that turn themselves into a frock. At one smart house in New York these masculine tailored suits for the street have the high-waisted skirt with a short, full white wash blouse above it. The jacket runs straight up and down and there is an ornamental belt, a narrow one, slip- iped about the waist line. _ When the coats fasten they do 5o in the most negligible manner, some- times with two buttons placed close together at the waist line. The re- vers are long and conspicuous on these coats. The open space is filled in with a frilled or tucked vest of white muslin which often stands out into a high straight collar rolling like ;2 hoop around the neck None of these collars are worn over the coat collar. There is no revival of that fashion. Neither is there a lendency to wear a round-necked Sweater blouse beneath the coat of the gind that omits the collar of white. Such accessories need care- ful and frequent laundering and are TH HIGH AND FLARING COLLAR OF CREAM LACE. women added the jewels of tre Arablan Nights to this foundation of black. The arms were covered with gittering bracelets. The neck was draped with beads, precious and semi-precious; each French woman seemed to have become Sinbad the Satlor and discovered a hiddem niche of jewels. B So much for the French. “They left little to the imagination in such cos- tumes. Few women were strikingly individual. The tilt of a hat and another jewel added to the collection made the only note of departure from the standardized costume. * % ¥ X France evidently liked this sort of thing. Her women are still Wearing black. As the spring breaks they show no chance of change in colors. They appear to be wedded to the shadow-like frocks and hats. If rumor s true that the smart women are beginning to stop the use of white cosmetics on_their faces, then the change from black to colors may be- gin. It was the excessive contrast between a face whitened like that of a clown, with scarlet lips painted to expr any expression, and the dead black gowns that thrilled the French sense of artistry. If they give up the white faces and the red lips they will find the black is not so alluring. The importance of this fashion strikes home to the Ameri- can because it has arrived on this shore fully armed for conquest. What will we do about it, is the question of the hour. The dressma:- ers have taken s Some have brought over very few of these grief- stricken frocks. Such, and they are the ones who dress the comspicuous set who leads fashion even when it is not always good, offered the new French gowns in this lusteriess color. Those that have these frocks for sale say the American woman will be glad to forsake colors. Those who will not touch them say the American woman is not physically built to carry One thing seems to be true: It will be necessary for the majority to whiten the faces and redden the lips in the French manner if they are to attempt to be smart and conspicuous in their new black costumes. It i3 not necessary to offer this use of cosmetics to the average Ameri- not appealing to the woman who has not a personal maid or a full drawer of neckwear in perfect condition. What the compromise will be is hard to tell. It is a question that makes many 2 woman pucker her brow. * % % % It is very much the fashion to wear a high wrapped collar of soft white fabric after the manner of Beau Brummell, but the woman with a large neck and the square chin does not look her best in this masculine covering for the neck. The slim woman who has an oval chin carries it off with distinction. This is a strange truth that runs through the gamut of dressing. The slender femi- nine woman can wear masculine clothes. The strong masculine wom- an needs feminine clothes. In each the contrast gives distinction. The American woman who is athletic dresses in a way to harden her and thereby does the worst harm to her- self. The straight sailor, the turn- over collar with its four-in-hand tfe, the sleek coiffure are the very things she should avoid, and yet she is the UL BEIGE CLOTH NODEL, WITH HIGH COLLAR AND DEEP CUFFS OF THE SAME MATERIAL, PLEATED. PAILLETTES OF JET AND THERE IS AN INNER COLLAR OF FLOWERED ORGANDY. mounted on net is still in high fash- ion. It is especially good in brilliant colors. As a proof of how strong an influence the cape exerts on spring costumery the new gowns show tiny shoulder capes dropping from collar to waist. These are of fringe silver cloth of latticed braid and of chiffon. Paul Poiret started this fashion the first peace summer. He made capes of silver net that could fold about the bare arms. Doucet made these capes on evening gowns and bordered them with pink roses. They did not become & general fashion until this spring, and now they are used on 1type that accentuates it. Sh may look her best in a tailored suit, but she should choose acceseories that | feminize it The woman who has a mind will ask what is to become of her capes, if she is to go back into tailored suits. The answer is that she can wear both. There is room enough in our hectic life for all manner of apparel. Neither garment ousts the other. es are worn over coat suits, if the truth e | Thero 1s nathing in the way off tas new jacket and skirt to guarantee that it will be warm enough on chill is a graceful adjunct and when it is attached to a shoulder band of fur it becomes invaluable. There are capes for formal frocks made of transparent crepe gathered into a shoulder band of soft peltry. For in- stance, one gray frock in town car- ries a Paris cape of gray crepe gath- ered to gray caracul. The cape is un- lined. The majority of capes trust to a single piece of cloth to do the an girl. She has the whitened face find {h reddened lips. She adopted the fashion three years ago and there are times when she comes perilously near looking like a clown. It would be hard on the woman who does not make up and who has slight coloring of her own. She would be wise to run from black as she would from the rain. It will drcnchhnut of her whatever person- lity she ma: sess. i .l'.’ll nlt.’v’r::llble that American women in mass will use more make- up than ever if black gowns become uglquitout The influénce of Spanish fashions tends to the use of cosmetics and the use of black, but if Amerl cans are really to study the costu ery of Spain and imitate it in even a slight degree they will find the col- ored shawl, the red rose, necessary sdjuncts to brilllancy. * % xS A varying procession of lusterless black gowns defiles past the observer, iving & woman a chance to clothe herself in this fashion for every hour of the day, unless she happens to pre- work. The plaid cape appears to have passed the zenith of its glory unless for sport use, .and brightly colored checks of broad blue and beige squares continue to serve in a ing manner for loose -circular capes, which are worn in the country or =i the seashore. The street cape is more sedate garment. When it d parts from blue. gray or tan it be- comes henna. This has a wearisome sound to it. because the henna cape was dragged to the ground last su- tumn, but the new one is quite allur- ing. It is a peasant’s sape of mottled homespun. It is trimmed at times with gray wool embroidery or a flat design of applied cloth. Satin capes are not in first fashion. but the black crepe de chine cape. without luster and trimmed with fringe, is ardently desired by many. The channel style, which is a gath- ered cape of thin material with a wide shoulder eollar that fastens in front, is still in the 1k Its successful rival of pe de chin draped.like a Spanish shawl. Doucet’s cape of cloth with wide cut-out bands ingle-track | l r Why not have several of these . bullt to rejuvenate one-plece frocks that are a bit the worse for wear or of whose simplicity one may be a bit weary. ‘With capes and aprons that can be put off and on one really has very little use for more than one or two chemise frocks. These serve as the ' foun ion of the wardrobe. ‘The skirt which has an_accordion pleating all around has vanished from the first ranks of fashion. The woman who possesses ome or more should not get discouraged. If she has the courage of her comvictions 4 A CAPE OF NATTIER BLUE CLOTH TIED WITH LONG ENDS OR SAME SHADE. days and for all climates. The cape|SILVER RIBBON AND WORN OVER A GEORGETTE FROCK OF THEB afternoon and morning frocks rather than on evening ones. * % k¥ From what source came the de- tached ornamental aprons? They are here in full power. The manne- quin walks down the salon wearing a white crepe de chine frock appar- ently trimmed with Spanish flounces and black lace and a girdle of black ribbon. Half-way down the salon she unties the girdle removes the ornamental apron of lace and reveals berself in a chemise frock in plain white. Curious trick. It seems to pervade the dressmaking houses. The mannequins drop capes to reveal frocks. They drop aprons and ap- ear in unadorned garments, they step out of skirts, let the public cover that their petticoats are of silver lace. To these detachable aprons there is no end. They are not always of lace. They appear on a simple morn- 1 frock of dead black crepe de chine. They will start as a fitted yoke at the waistline with long loops at Intervals; these loops turn up at the hem to form sling: Again they will start as a string girdle and drop in panels of accordion hem of the skirt. always removes them half-way down the room. The fashion Instantly started thought of economy &mONE WOMEN. e I she will continue to wear them. They slenderize the gure. ‘The bex- pleated skirt is taboo. The only kind of pleatipg that is fashionable seems to have been gone over by & steam roller. It §s so soft and fine that it seems to have been woven in the ma- terial. It is used in panels and panels are plentiful. They do not pear above the waist, but they con- tributed a quota of success to the majority of day-time skirts. 3 If the American continent is m to accept a multitude of inky gowns without color attached, there must be a quantity of pleating and applications of points fringea, of mMIeln’l.m‘l hemstitching to e plainness. lt‘;! quite evident from the exhibi- tions of French and American clotheg that all these accessories will be in constant usage this season. Some gowns use up all of them at once, and the effect is not overelaborate. As the fabric is fine and no color arises to clash against the eye, one does not get & full realisation of the handicraft empleyed on the gown un- til it is handied in the hands. When women were told that' em. broidery had disappeared beca its price put a burden upon the X, they were foolish enough to believe that the cost of gowns would be les- sened. Woe is wi ‘The amount oman. of thiy that the dressmakers z broidery would ngressiol rd.