Evening Star Newspaper, November 6, 1897, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

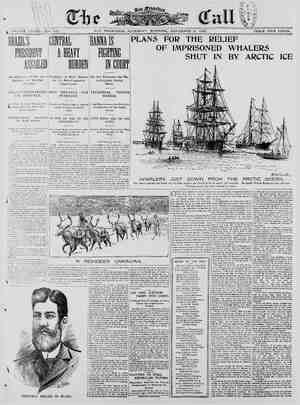

THE EVENING STAR, SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1897—24 PAGES. —— ‘ 23 GETTING WAR NEWS What It Costs to Get to the Front. HOW DISPATCHES ARE SENT HOME The Correspondent Must Learn to Rough It. MANY NARROW ESCAPES From Tit-Bits. The millions of newspaper readers who, in time of war, eagerly devour the more or less realistic accounts which appear in their morning papers have perhaps never given much thought as to how such intelli- gence is collated and meted out to the pub- lic: and it probably never occurs to them that while they read the paper in com- fort the writer may be in dire danger un- der shot and shell, seeking a moment's rest after thirty hours of ceaseless excite ment, or hunting for a meal to satisfy the gnawing pains of hunger. But such riences are common to the war correspondent, who carries his life in his hands and braves dangers daily such as few men are ever called upon to face. Newspaper readers who compiain of late- ness of news in time of war can have no idea of the difficulties under which it is sent home. The correspondent, after re- ceiving his impressions of a battle with the aid of the telescope, must frequently eighty or a hundred miles before he can put his letter on the wires, and must write as he rides. Sometimes, if he is for- tunate enouzh to get hold of a sensational piece of exclusive news, he will charter a special t or steamer at immense cost and pay heavy special rates for transmis- sion. Censorship. But even when this is done, he has no guarantee that his letter will reach home for some days. The telegraph Is a slow in- strument in war time, and the wires are nearly always either blocked or engaged. When a press censorship is adopted tele- grams are often detained in the post office wo or three days, though their transmis- sion is a matter of the utmost importance, and everybody at home is waiting anxious- ly for the intelligence contained in them. When at last the telegram is dispatched, supposing it is an important one, it rarely bears much resemblance to the original copy The censor does not hesitate to muti- late the report at his pleasure, and in this way facts are often entirely reversed. In the recent war betwen Grece and Turkey, for instance, a correspondent Wrote: “The prince this morning rode through the streets uncheered,” but on reaching England the message read: “The prince this morning rode through the Streets loudly cheered.” Similarly, in the news of the defeat, names were altered so as to make it appear that the defeated side had been victorious. A war correspondent’s expenses are, of course, very heavy. The bicycle will prob- bly be largely used fn future wars, but herto the correspondent has depended on horses and carriages, which can sel- dom be hired under £5 for a single journey. Then an interpreter is usually engaged by correspondents of first-class papers, which brings the bill up considerably. It is a fact that the incidental expenses of one correspondent in the recent eastern war reached ) before fighting had actually commenced. Long Dispatches. Altogether there were some twenty cor- respondents engaged in wiring their im- pressions to all parts of the world, and tel- egraphic, traveling and living expenses | must have run into tens of thousands of pounds. The American correspondents spent an almost unlimited amount, chartering special Steamers with the utmost freedom. The | Times correspondents were paid at the | qr of 000 a year, and in addition re- ceived £3 a day for expenses. On one sent home a telegraphic mes: words long zraphic rate ¥#s 7d. a word, must have cost about £v. | The rate for urgent telegrams—which sim- ply meant that the me Ssage was to be dis- Patched without long de! lay—was 1s. 9d. per word. Quite a quarter of a million words must have been telegraphed from Athens and Constantinople during the war, and the probability is that the total number would be nearer half a million. Reckoning it at enly a quarter of a million, however, the est of the dispatches, directly and ‘indi-| en less than necessary to travel off a telegram, locai sometimes within stations tof a Li th confidence. The jon paper on Gne sent telegram from wherce it had to be on its way to Lond ortant and exclusive, Trespondent prided himself on | good picce of work. Four | later, however, he was breakfastinz erintendent of telegraphs in an el, when his co yerintendent for tr: Rough Life war correspendent must be prepared it. No downy bed awaits him at the end of a weary day. He must turn in- to seme deserted house within earshot of the “front,” and sleep as lightly as he can, was brought nsmission! with a loaded gun at hand. By the time war is over he has almost forgotten to undress at it time. His shoes are scare ff his feet, ani he s clotkes for weeks together. He must be with one course . OF with e, unless he can re it him ssaly we lived on lambs which the | rs killed, or which we cot It was not us ‘The peas- y fled before the advance of Hl jeaving their little homes al- | What became of the poor fugitives h aven only Knows, but their houses were havens of rest to rv in that strange and troubled I have never met anybody after returning frow the seat of war who has not been curious to know what war is like. With the recent war fresh in my mind, it seems to me that a spectacle the best com- parison is the stage on a big night at the opera, viewed through the reverse end of an opera glass. War ts like that. Awful Scenes. It is subme—as a spectacle—from a dis- tance. It is when you get nearer the fight- ing that you realize the sickening horror of it all. One man—a Greek offtcer—fell dead within three feet of me. I brought away the piece of shell which killed him. His fel'ow-o:ficers picked him up and kissed him, and he was carried away. It is « terrible thing to see a man killed in war. I saw the light fade out of the soldier’ and he looked like a wax fig- ure rather than a man who had been lead- ing men a moment before. I had many narrow estapes myself. Once when passing through a ravine I suddenly heard iiring, and on emerging from the narrow 3 I discovered that I was the object aimed at. It is a horrible sensation. Shots flew in all directions, whizzing past ™my ears. The most awful fact of it all is thi cannot see where the shots come from. The enemy may be miles away, but the fire plays around you, threatening every moment to cut the thread on which you. life hangs. ‘The thing which most surprised me in the eastern war was the callousness of many of the soldiers. They joked and laughed and smoked cigarettes as though war were ehild’s play, and it was only when a com- rade feli wounded or dead that you saw “that thay had hearts to feel and eyes that glistened. The Turks carried charms in their breast poekets—iong scrolls of paper containing an extract from the Koran. I have one on my table as I write, vividly re- calling the white face and fearful expres- sion of the dead soldier from whose pocket I took it. SS oe ‘The Grand Canyon of the Colorado will be invaded by the trolley, a line being pro- posed from Flagstaff to the very crest of WITHOUT LESE MAJESTE. the Art of Insulting German Princes With Impunity, m the New York Sun. ‘Three years ago this fall the editor of one of the countless Volkszeitungs in Germany sat in court answering the familiar charge of insulting a prince. “You are the responsible editor of the Ikszeitung?” asked the presiding judge. “Iam.” “And as such you are named in every issue of the Volkszeitung?” “I am.” * * “Did you write the article which gave rise to this action?” “I did not."* “What class of articles do you write?” “TI do not write any articles.” “What, then, are your duties?” “I sweep the office and receive the cards of persons who wish to see the editors.” “What eise?” ‘Weil, in winter I build the fires and keep em going.” ‘Is that all?” “No. I dust the desks and see that each gentleman has his paper and ink ready for work, and scour the windows, and some- times help distribute the papers.” “Anything else?” “Why, your honor, what do you expect for 60 marks (315) a month?" The Koelnische Zeitung, which reported the trial, cut short at this point in its ac- count of the examination of the Voiks- zeitung’s responsible editor and fell io mor- alizing on the deceptions and tricks which laws regarding insult of majesty, otherwise known as majestaetshelizdigung, or lese majeste, had forced upon the German press. Of course, the editor on trial was no editor at all, except in name. He recived bis $15 a@ month merely as janitor. Though he was announced, to satisfy the law, in cvery issue of the Volkszeitung as the responsible editor, he had never penned a line for its columns. For this very reason he had been selected to bear the legal responsibility for the men who wrote the newspaper. If ar- rested, tried and imprisoned he never would be missed. The Volkszeitung would take on nother janitor from its wait list, for even in over-educated Germany janitors are much more abundant than editors. Such is the institution of the jail editor in Germany. It is calculated solely to thwart by a trick the oppressive provisions of the press law and to fortify the newspaper bus- iness against the periodical onsliughts cf or Fi Vv. crown prosecutors. Without it only the dyed-in-the-wool monarchist would be able to publish continuously a daily newspaper, for the law is unbending, the crown law yers are fanatically zealous and the com- plaints from Berlin flutter down like the leaves of autumn. os CLEARED FOR ACTION. A Modern Battle Ship Presents an Unusual Spectacle. R. F. Zogbaum in Harper’s Weekly. A battle ship cleared for action presents an appearance differing greatly from that shown while lying peacefully at anchor in Port. Stanchions, davits, everything mov- able not specially designed for fighting pur- Poses, disappear from the decks and sides; brass-barred skylights to lower decks and cabins, rails and supports about the open- ings leading below, give way to steel battle hatches; hose is coupled to the fire pumps and laid along the deck; cireular openings to the ammunition Passages yawn, traps to the feet of the unwary; and everything that might interfere with the sweep of the suns or the freedom of movement of the crew vanishes from sight as completely as if it never had existed. The stenciled word “overboard” on chests on the deck—chests containing anything inflammable, as paint, alcohol or oil—indicates that in the pres- ence of the enemy they would disappear over the side of the ship into the sea, while the boats are hoisted from their rests on the superstructure and lowered to be towed astern—perhaps even to be cast adrift—to avoid injury to Ufe and limb from flying splinters under the enemy's fire. The shock and noise of action, as the ship comes cn the firing line, is something beyond descrip- tion. Take ships Mke Iowa and Indiana, for Instance, where a single discharge from bow to quarter of the principal batteries Bive a weight of fire of 4,499 and 5,600 Pounds, respectively, and the tremendous shock of the explosion may be dimly im- Zined by one who has not experienced it. Il more trying to the nervous senses are the sharp thudding reports of the rapid-fire guns, vomiting forth their deadly missiles at the rate of four or five shots every min- ute. Night practice with the auxiliary hat- teries gives an exhibition of the murderous work these guns are capable of, and the drifting targets—mere handkerchiefs in ap- pearance as compared with attacking tcr- pedo hoats—are greeted with such a storm of projectiles that nothing coming under the rays of the search light could live for a moment. Only by the simultaneous rush of a number of those small, but terrible, en- gines of marine warfare, torpedo boats, could there be much chance of inflicting injury to the larger ships. By luck cr through superiog skill one might “get in” and successfully explode its torpedo azainst the side of {ts huge enemy, but the attack would be much of the nature of the charge of a “forlorn hope” of bygone times into a breach in the wall of a hostile fortress. But eggs are broken when omelets are de, and war, on shore or at sea, is a rdous game, and the loss of half a of torpedo boats would count for less than the de ‘uction of an enemy’s battle ship. Cavalry acts against cavalry in war id; torpedo boats are, to a ceriain ex- tent, the c: ry of the sea. Torpedo-boat destroyers—torpedo boats of large size superior speed—form valuable adjuncts fleet of war ships, cruising as scouts and videttes, and guarding by their vigilance the lines of approach to the main body of the squadron. In the absence of such craft, as in the absence of cavalry with an army. the fleet is seriously handicapped, and the chances of loss of some of {ts number through the enemy’s torpedoes are much greater, in spite of searchlights and rapid- fire ordnance. At present our entire force of torpedo craft con: s of four boats in service and one torpedo-boat destroyer, and fourteen torpedo boats in the hands of the builders. SS He Had a Good Salary. James Payn tells of a well-known singer many years ago who, in the pride of his heart, greatly exaggerated to the tax col- lector his own assessment. “The fact ‘s, he confessed to the commissioners, “I have not a thousand pence of certain income.” “But are you not stage manager to the opera house?” “Yes, but there is no saiary attached to it.’ “But you teach?” “Yes, but IT have no pupils.” “Then you are a concert singer.” “True, but I have no en- gagements.” “At all events, you have a very good salary at Drury Lane.” “A very cod one, but, then, it’s never paid.” Un- der these cireumstances the tax was remit- ted. ——+ox+_____ What is a Biddlet From the Chicago Record. Although the name of Biddle is a well- known one to many besides the four hun- dred of Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Washington, Baltimore and elsewhere, it seems that this magic name conveyed only dense confusion to a foreigner once visit- ing the city of brotherly love, as proved by the following little story: After a sojourn for a week in that quiet but delightful place, where he was feted and honored to his heart's content, he asked a friend con- ficentially: “Can you tell me what they mean here by a ‘biddle’? I hear it con- tinually and on all sides ‘She is a biddle’— ‘Oh, he is a biddle, you know’—‘They are all right, of course, they are biddles.’ Now: what in the name of all that is unmention- able is a biddle?” —_—_-se—___ Vagaries of English Law. From Tit-Bits. “If a man,” says an intelligent detective officer, “is found sleeping out without the wherewithal to procure a lodging he can be fined or imprisoned, but if a sum sutti- cient for that purpose be found on him he cannot be touched. “Then, again, you are perfectly at lib- erty to throw as much dirty water as you please over an intruder into your house— provided, that is, that he has no legitimate excuse for remaining there; but should you honor him with a douche of clean water, you are Hable to a prosecution for wasting the same. “If a man goes into a public house and says, ‘Give me a glass of beer, please,’ they cannot make him pay for it. And if you are not twenty-one they cannot recover NEGROES OF SURINAM They Have Their Republics in South Ameri- can Forests, They Were Sent Into the Bush by Their Owners to Escape the Tax Gatherer and Stayed There. From the Surinam ‘Gold Fields.” Among the inhabitants of Surinam not the least interesting are the bush negroes, or, as the Surinam Dutch call them, “bosch” negroes. These negroes are the descendants of the maroons or runaway slaves of the old time. They live in the woods of the interior, and may be said to be the agriculturists of the colony. The first migration to the woods by these ne- grees was made in 1663. In that year the Pertuguese Jews of the Surinam valley, when the tax gatherers came around, sent their negro slaves into the woods to avoid paying taxes for them, expecting that after the departure of the revenue agents the negroes would return. But they did not. They remained in the forest, established themselves there, and received constant ac- cessions to their numbers from the runaway slaves of the settlements and the neighbor- ing islands. After the emancipation act of 183 they received large accessions from the negro population of Barbadoes. They have had many conflicts with the government of the colony during their history, in the as- sertion of their freedom and independence, and have always maintained both. One of their great leaders was the famous Boni, who, in 1772, led his bands up to the very walls of Paramaribo. They have had inde- pendent republics, and have generally held themselves to be independent of the colonial laws. They are, however, a peaceable peo- ple, mild and—unlike the aborigines—tem- perate. They cultivate rice and other pro- ducts, whicn- they dispose of to the col- onists. They are also the wood-cutters of the colony, and conyey by the rivers, streams and canals the products of the for- ests to Paramaribe. They are fairly indus- trious; they have no religion, their only object of worship being the ceiba, or cotton tree, which is sometimes found rising in majestic and solitary grandeur in the clear- ings, having been spared by the ax because of the veneration in which it is held. Of- ferings of fowls, yams and manioc are often found beneath the ceiba, the pro- pitiatory gifts of the bush-men. The Mora- vian missionaries have labored hard to bring the bush negro into the fold of Chris- tianity, but without success. A large proportion of the population is composed of coolies, hill coolies from the hill lands of India, south of the great bend of the river Ganges, and coolies from Java and China. The coolies were introduced after the emancipation of the slaves, to take the place of the latter on the planta- tions. The British were the first to intro- duce this element of labor, their own slaves having been emancipated in 1838. When the emancipation act went into effect in Suri- ham, and the plantation negroes declined to lerger perform the labor which wag compul- sory upon the in slavery,it became necessary. to look for labor elsewhere. The British Indian authorities required such guaran- tees before permitting the coolies to leave India that only the richest planters could afford to secure this kind of help. The poorer planters who had not abandoned their plantations turned to the Dutch col- onies of the Pacific for relief in their ex- tremity, and succeeded in importing a num- ber of Javanese coolies, who now form an element of the population of the colony. Later, large numbers of Indian coolies and Chinese were brought in, also Arabs, na- tives of Annam, and even negroes from the Senegal. The coolies, without exception, are industrious and willing to work. The labor on the sugar and coffee plantations is inly perfermed by them, but they are feund in every department of industry, many of them settling down after their term of contract has expired and becoming a part of the colony. ‘they keep up the cus- toms of the countries to which they belong and wear the same fashion of dress, that of the Indian women being exceedingly pic- turesque. These females wear a great deal of jewelry, consisting of armlets and anklets of gold, necklaces of coins, finger rings in great abundance, and many of them wear nose jewels. The Indian coolie women are for the most part handsome of face and shapely of figure. ———~ee——___ JAPANESE DESIGNS. Largely the Result of Their Methods of Teaching Drawing. From the Upholsterer. The question is often asked, “Where do the Japanese get the ideas from whieh to produce the weird and fantastic designs so often seen in their work?” Numerous ef- forts have been made to answer this ques-. tion, and the Japanese have been alter- nately lauded for the beauty of their work and condemned for its crudeness. It would appear that the system by which the Ja- panese are taught designing is largely re- sponsible for the character of their work. There is no race of people on the face of the earth, with the possible exception of the Chinese, who are more painstaking or skillful in the work which they perform. The Japanese student who is taught drawing is given a smali book in which are designs printed in small squares, and these e reproduces square by square until he has grasped the salient features of each. He is then sent out into the open coun- try and told to observe the works of na- ture spread out before him in all their lux- uriance. Finding some suitable object for his at- tention, he proceeds to reproduce the same, introducing, perhaps, some imaginative de- tails. It is right here that the system of squares comes in. Those elegant stems, those feathery petals which are apparently thrown together without restraint, are simply the particular feature of the’ mass of vegetation whith he has selected for tis individual study. His long course of study in this line has given him the fac- ulty of following a single vine through tangled underbrush and ignoring all the rest of the growth. The tortuous course of this one vine when brought out by his ready brush appears to the western art critic 2s crude and without merit, whereas in reality it is catchy and full of interest. The wonderful facility of the Japanese in the production of works of art, in the execution, the beauty of colorings and the delicacy of their drawings, is well known. While artists claim the designs of the Ja- panese, if critically examined, will be found incorrect in form, proportion and construction, these same critics freely con- cede that in the failings mentioned are found the very highest merits of the Ja- panese as decorative artists. Decorative art does not admit of abso- lute fidelity to nature. Slavish copyists lack imagination, without which they can never be true decorative artists. The very science of the art is the power to con- ventionalize nature while preserving the spirit and following all the objects repre- sented, and this is where the Japanese excel, as, gifted with a wonderful quick- ness of perception and delicacy of hand, they seize upon and reproduce with extr: erdinary rapidity and power of touch the ckaracteristics of natural objects. ——__. A Jewish Colony at Cyprus. From the Jewish Chronicle. A remarkable petition has been addressed to the Queen of England by a number of Jews who are at present following a useful career as artisans in the city of Jerusalem. The signatories beg that her majesty will, through the secretary of state for the colo- nies, permit the establishment of a Jewish agricultural settlement on the Island of Cyprus. There are two distinct morals to be drawn from this incident. In the first instance, it is becoming clear in many places a longing for a return to farming and culture is seizing hold of the Jews. Ar- tisans and workers in cities do not easily reconcile themselves to the serener, duller hfe of the fields. Indeed, the stream is the other way—from the farm to the town. But there is another striking fact about the petition of Jerusalem Jews to our queen. The action gives point to the doubt whether Palestine is in truth the best fleld for fur- ther colonizing effort. Cyprus, under Brit- ish government, evidently has more charm for some Jews already settled in Palestine than Palestine under the sultan. RANDOM VERSE. Written for The Evening Star. Joaquin mitflt} Deserted Cabin. Here have you lived éh, Poet of the West— Here has your heart, all weary of the strife Like a song-bird tis a sheltered nest And saug amidst the, Woodland’s peaceful life, The soft winds sightng ‘midst the autumn leaves Eeho, I dream, tig:stwis they heard of yore? The sunshine with dow lightly weaves A web of silence "gound: your cabin door. ‘Zhe rich rose pioonliag inst the narrow panes ‘Holds in its heart the fight of other days When you were walking An these quict lanes, Filling with music. all these silent ways. Oh, Uttle cabin ‘neath tte giant trees! Ob, silent home, oh, Jong-deserted nest! Still haunted by the ghosts of melodies Sung by the sweetest Song-bird of the West! ANNIE LANDRETH PERKINS. —>—_— Written for The Evening Star. A Memory. Dedicated to K. L. Y. In the woodland bowers I met her, When the May flowers were in blooms And I never can forget her, ‘Though she’s sleeping in the tomb; On fond memory's page are shining Visions of the buried past; And my heart with grief is pining; I shall love her to the last. Her bright spirit Ungers near me In my hours of grief and pain; Angel whispers come to cheer me, With their sweet and tender strainy Yet, I know in some far Aiden We shall meet among the blest, Where no care our lives can laden, ‘And where souls find peace and rest. JOHN A. JOYCE. The Klondike. Walter Malone in Harper's Weekly. lL rapped in a robe of everlasting snow, we ley blasts eternal revel hold, here giunt pines shiver in the piercing cold, Where inellow summer nooutides never glow, And sleety crags no springtime ever know— Thus, like a nuser, in his freesing fold, ‘The ‘Aretie King las gathered heaps of gold To lead deluded wanderers unio woe. So in his radiant diamond palace there, Amid white splendors of his thousand thrones, Where keen auroras glitter, blaze, and glare, ‘And like a Wandering Jew ‘the wild wind moans; He smiles at wretches in their last despair, Who dig for gold among their Comrades’ bones, 1. bout my bome I sce the springtime bloom, fo make me glid, the robin lends its lute, ‘Tho lilies blossom, lilacs breathe perfume, The red leaves flutter, golden usters loom Around me; tones of loved ones, never mute, Are sweeter than the ‘viol or the flute Through June-time gladness or December gloom. ‘The daffodils their golden treasures pour By lapfuls to my children as they play; ‘Tie vines, with clustered rubles at my ‘door, Gladden hy good wife through the livelong days So in this humble nest, my wealth is more ‘Than all the gold and silver dug from clay. een ee A Boy’s King. 8. E. Kiser in Cleveland Leader. ‘My papa, he’s the bestest man . Yhat ever lived, I bet, And I ain't never seen no one As smart as he is yet. Why, he knows everything almost But mamma says that he Aln’t never been the President, ‘Atd that surprises me. And often papa talks about ‘How he must work away— He's got to toil for other folks, And do what thers’ say; And that’s a thing tliat bothers me— ‘When he’s so good ‘and great, He ought, I think, at least to be ‘The gov'nor of the state! He knows the rames of lots of stars, And he knows all the trees, And he can tell ‘the different kinds Of all the birds he’ sees, And he can multiply and add Aud figure in hts héad— ‘They wight haté bedn some smarter men, But [bet you’ they ‘tre dead. Once when he thought I wasn’t near He talked to jiitunma then, And told hey hdyw-he yates to be The slave of other men, And bow he wished that he was rich For her and me--any Don't know what mide me do tt, bat Ehud to goapd crys, opype ys And $0 when dat ‘off hig knee T ast him: ““Ig.it tine That you're a ehifgiand have to toll When others tel you, to? You are so big and oud apd wise, You surely ought to be. The Presidyit, tusteud of Just A slave, Ht seems to te. And then; the tears came in bis eyes, ‘And le hugged me tight and said: “Why, no, my dear, I'm not a slave What put that in your head? Zam a king—the happiest king That ever yet held sway, And only God can take my throne ‘And my little realm awa; The Weaver. From the Carpet and Upholstery Trade Review, Beside the loom of life I stand And watch the busy shuttle go; The threads I hold within my hand Make up the filling; strand on strand ‘They slip my fingers through, and so This web of mine fills out apace, While I stand ever in my plic One time the wool fs smooth and fine And colored with a sunny dye; Aguin the threads so rougoly twine And weave so darkly line on line My heart misgives me. Then would I Fain lose this web—begin anew— But that, alas! I cannot do. Some day the web will all be done, ‘The shuttle quiet in its place, From out my hold the threads be run; And friends, at setting of the sun, Will come to look upon my face, And say: “Mistakes she made not few, Yet wove, perchance, as best she kne Se ee In That Day. From the New England Magazine. Lord, if I find no place among Thy sheep, In pastures fair above, Yet grant me—straying with the goats—to keep Some tether of Thy love. And thongh emparsdised on ‘Thy right band I never may appear, Deny me aot this only grace—to stand ‘Thy left exceeding rear! —_—__ 6. A Charaeter. From the Pittsburg Bulletin. He sowed, and hoped for reaping— A happy man,.and wise; ‘The clouds—they did his weeping, ‘The wind—it sighed his sighs. He made what Fortune brought him ‘The limit of desire; ‘Thanked God for shade in summer days, In winter time, for fire. When tempest, as with vengeful rod, Tils earthly mansion clefts On the blanic sod,: he still thanked God Life and the land were left! Content, his earthly race he ran, ‘And died—so people say— Some ten years later than the man Who worried his life away. A Woman’s Leve. A sentinel angel, sitting high in glory, Heard this shrili wail ring out from.purgatory. “Have mercy, mighty angel, hear my story! 5 1 “I loved,—and, blint) with passionate love, I fell. Love ae ihe dawn to death, and death to Hell; For God 1s just, an@/death! for sin is well. 1k TE “I do not rage against thi high decree, Nor for myself do ask that oe shall be But for my love oniearth Xfho mourns for me. “Great Spirit! let me see my love again, And comfort him ovg hour, and I were fain To pay a thousand Years of fire and pain.”” ‘Then said the pitying an That wild vow! -finger’s bent Down to the last hgur of thy punishment!”’ But still she wafled:"T pgily thee, T cannot rise to pz ‘love him 0. O, let me soothe him in hjs bitter woe!” ‘The brazen gates griu And upward joyous tie aeian She rose and Vanistidd in the et But soon adown the‘Aying‘yunsct sailing, And like a wounded, tp pg ah ea T found him by the summer sea Realaeds his het iden’s knee iden’s. She curled his hair and kissed him. ‘Woo ts me!” She wept, “Now let 1 Thnve cen fond and trolish. ‘Let me fa ‘To explate my sorrow and my sin.” ajar, star, far. ‘The To be TORTOISE SHELL HUNTING The Process is One of Extreme Gruclty. Fires Set on the Living Turtle to Separate the Bony Layers of the House He Lives In, From the New York Post. There are many articles of daily and hourly use, constantly pressing before our eyes and through our hands, about the pro- duction of which we know comparatively little or nothing. An interesting example of this is tortoise shell, from which combs and hairpins are made, besides a multitude of trinkets for the dressing tables, the desk and the pocket. Fierce crusades have been instituted in recent years against the slaughter of birds for the procurement of their plumage for hat trimmings, and yet I venture to say that the process of procur- ing tortoise shell is a cruelty to animal life which far exceeds that to which birds are subjected. In the eighties I happened to be down in Bluefields, on that awful Mosquito coast, and at the invitation of one Manuel La- tona, who was the owner and captain of a small schooner, went with him to the cay El Roncador for tortoise shell. This cay gets its name (which in English would be The Snorer) from the exceedingly angry surf, which can be heard for a long dis- tance breaking over the reefs. This is the cay on which, a couple of years back, the historic oid ship Constitution was wrecked and battered to pieces. El Roncador is nothing more nor less than a typical coral island, such as is found throughout the southern seas, three-quarters of a mile long, perhaps, and not more than a quarter of a mile across its widest part. Surround- ing the island is a reef, inside of which the water is smooth and rather shallow; and at the bottom of this shallow water there grows a peculiar kind of sea grass, ich is a dainty food for the turtle tribes. There is also found on the top of the water inside the reef a sort of small blubber fish, called in Spanish dedalcs, or thimble fish, which is, perhaps, the greatest delicacy of the en- tire turtle menu, The turtle whose shell is valued in com- merce is a small species known as_ the hawk’s bill. There are other varieties which come to El Roncador to spawn, but they are not molested. During the night the turtles crawl up on the shore to lay their eggs, each female depositing on an average about seventy. To do this they dig holes in the sand about two feet deep, and after laying the eggs cover them over so deftly that it is almost impossible for a novice to find them. These eggs are really delicious when roasted, but the turtle fishers are careful not to destroy those they do not take for food, so as to promote as much as possible the increase of this valuable sea reptile. At night the fishers conceal them- selves along the shore as well as possible, and when the turtles come up out of the water on the beach, they rush forth and turn them over on their back with iron hooks, leaving them secure in this position until morning. The tortoise shell of commerce is not, as ‘generally believed, the horny covering or shell proper of the turtle; it is the scales which cover the shield. These scales are thirteen in number, eight of them being flat and the other five somewhat curved. Four of those that are flat are quite large, sometimes being es much as twelve inches long and seven inches broad, nearly trans- parent and beautifully variegated in color with red, yellow, white and dark brown clouds, which give the effects so fully brought out when the shell is properly pol- ished. A turtle of average size will furnish about eight pounds of these laminae, or scales, each piece being from an eighth to a quarter of an inch in thickness. it is the methed by which these scales are loosened which is the repulsive part of the business. The turtles are not killed, as that would lead to their extermination in a very few years. After capturing them the fishers wait for daylight to complete the work. The turtles are turned over again ii-their natural position and fastened firmly to the ground by means of pegs: then a bunch of dried leaves or seagrass is spread eveniy over the back of the turtle and set afire. The heat is not great enough to injure the shell, merely causing it to separate the joints. A large blade, very similar in shape to a chemist’s spatula, is then inserted horizontally between the lam- inae, which are gently pried from the back. Great care must be taken not to injure the shell by too much heat, and yet it is not forced off until it is fully prepared for sep- aration by a sufficient amount of warmth. The operation, as one may readily imag- ine, is the extreme of cruelty, and many turtles de not survive it. Most of them do live, however, and thrive, and in time grow @ new covering, just as a man will grow a new finger najl in place of one he might lose. The peculiarity of the second growth of shell, though, is that instead of repro- ducing the original number of thirteen seg- ments, it is restored in one solid piece. To see the operation of taking the shell from the living turtle once is about alla man of northern breeding wants of it; and if the helpless reptiles had the Power of voicing their sufferings under it, their cries would tell of as heartless a business as man has yet engaged in. +o~— Drive a Needle Through a Copper. Harry Kellar in the Home Journal. An apparent mechanical impossibility may be accomplished by simple means, us- ing a copper cent, and a cork, with a com- mon cambric needle as accessories. An- nounce that you will drive a small needle through a coin, and few will be ready to accept your statement, yet it is very sim- ple and any one can do it. Take a copper coin, place it upon two small blocks of wood, leaving a very narrow open space between the blocks. Now, having selected a good, sound cork, force the needle through it until the point just appears at the other end. Break off the portion of the head of the needle showing above the top of the cork. Place the cork upon the coin and strike it a fair, smart blow with a hammer. The needle will be driven en- tirely through the penny by a single blow. A Royal Electrician. Speaking of the Prince of Naples, Signor Giarelli says: ‘‘His hobbies are of a scien- tific nature. He is, perhaps, the only real electrician among all the present princes of Burope. He has never occupied himself much with literature, music or painting, but he is a master of electric mechanism. He is very learned in all that concerns the application of electricity to light, motive power, sound and photography. He was one of the first and most successful experi- menters with the X rays after their dis- covery, and ir Rome his residence in the Quirinal had the aspect, during his royal highness’ bachelor days, of a scientific Jaboratory.' —————+es_____ Hardy Table Plants. From the New York Tribune, The Mexican palm grass is a thrifty plant for a centerpiece for the dining table. It is a hardy grower and is espe- cially effective. A primrose is also pretty, and it may be preserved by placing it for several hours every day in the window, where the sun can reach it. A fern should be kept in a north room. In selecting a plant for decoration at this season, when it is possible to find one that has been grown out of doors, it will be found to be more hardy, and consequently the blossom will last longer. ‘When a young maiden is about to be married in the Welseh-Tyrol, immediately before she eteps across the threshold of BEE MOUNTA ere eres |FINEST IN THE WORLD Occupied by Snakes. From the Galveston News. About twenty miles from Cleburne, on the Brazos river, is Bee mountain. On one side it rises several hundred feet above the country around and the other fronts the river and rises perpendicularly for 5W feet. On the perpendicular side are several crev- asses or Caves, in which places are millions of bees and tons upon tons of honey. It is impossible to scale the dizzy heights from below, although the rocks are worn- out places that look like steps had been made to climb this mountain ages and ages ago, and it is believed by some that aborig- ines scaled this cliff to procure honey for their primitive meals. Within the memory of man, however, parties have been daring enough to have themselves suspended with a rope and let down to where the bees enter the rocky bluff, and the tales they told of the vast amount of honey wouid sound like a story from the “Arabian Nights.” One man, a cowboy, who worked on the old Abe Wilson ranch, which was quite fa- mous here in an early day, had the tem- erity to have some of his co-laborers let him down with a rope. Where the bees en- tered, he said, the crevasses were not large enough for a man to enter, but a little south of that point was a hole about four feet high and eight or ten feet wide, which he entered. What he saw simply struck him dumb with amazement. There, hang- ing from the top of the cave, which seemed to extend for a quarter of a mile back, great combs of honey twenty or thirty feet long and from four to six feet wide. They looked like a great lot of fine silk lace cur- tains hanging in some grand old hallway. The humming of the bees sounded like the noise of many spindles in a great factory. He had a hunting knife with him and sliced off a piece of the honey and ate it, and was just about to slice off more to bring to his companions on the mountain above, and who were waiting to pull him up, when his attention was drawn to another direc- tion. On listening closely he detected a hissing sound and one unlike that made by the bees. Presently, from the direction from whence the sound proceeded, he saw at least 100 serpents coming toward him, their little beadlike eyes shining in the glare of the torch he carried. T use a street phrase, he “tore out,” leaving his hunting knife and this Klondike of honey behind. When his friends had pulled him up he had fainted from the fright. When he recovered he told them what he had seen. At first they laughed at him, but finally it became an accepted fact that in Bee mountain there are tons of money, but no one since that time has ever been reck- less enough to venture in that cave, where not only millions of bees and tons of honey are to be found, but where a den of ser- bents greets the intruder. Alderman Tom Childress has a summer home which ad- joins this mountain, and is going to tunnel into the side of it and try to arrange to ex- terminate the serpents and have this won- der to exhibit to his friends. ——~+o+_____ Importance of Trifles, From the London Times, Was it not Pascal who said that if Cleo- patra’s nose had been an inch longer or shorter it might have changed the course of history? Very likely, inasmuch as his- tory is ncthing under the sun but a tale about vast numbers of people. And what alters the direction of one life may easily affect millions. You have, no doubt, heard the story about the Earl of Wiltshire’s dog. It was at the time the divorce of Henry VIII was under discussion at Rome. Things were progressing favorably, and when the pontiff, at the close of the audience, put out his foot to be kissed by the earl, the dog—who had followed his master into court—bit it. This so enraged the pope and horrified the officials present that the Lego- tiations were broken off. This story may be true, or not, but we are all aware ti:at the course of history was changed about that time. Such things merely illustrate the truism that you never can judge +f the importance of anything by the size of it. A nod o fthe head cr a wink of the eye does sometimes literally and truly “speak volumes.” On a tense narpstriug it needs only the touch of a finger ‘o elicit a tone icud enough to fill St. Paul's Cathedral; and just an accidental word or two, drcp- ped in passing conversation, may, all un- bekncwn to the parties speaking, be a mat- ter of life or death to one or both of them. a Sg The Increase of Homes, Brom Leslie's Weekly. One of the best possible facts in the latter-day progress of this country is the increase in the number of homes. In crowded centers of population, such as New York and one or two other cities, the flat and the hotel must always be necessary, for space is too valuable to be monopolized by the humble. But even around the very large cities there are be- ing built thousards and thousands of su- burban cottages and country residences, and all through the length and breadth of the country, in the towns, villages and cities, artistic homes are increasing at an astonishing rate. If any one will take the trouble to look up the literature on the subject he will find that in this coun- try there are more than a hundred papers devoted to these home builders, giving them each week plans ard suggestions. The number of books upon low-priced architecture, written in the past fifteen years, exceeds the total for a century pre- vious. A wider education is being spread, and the gain in every way is enormous. A man who owns his home is a better citizen, even if there is a morigage on it. There is a feeling of personal partnership in the protection of property and the preservation of public order which makes him stand for what is bes: in law and goy- ernment. It is the best possible thing for his wife and children; best for him and best for the country. SES ee Dick’s Coffee House Closed. London Letter to the Philadelphia Ledger. Another landmark of Literary London has just disappeared, Dick’s coffee house having closed its doors. Already the work of de- molition has begun, and the quaint littie room to which briefless barristers and Bo- hemian journalists used to find their way for dinner down the narrow passage in the temple leading out of Hare court stands roofiess and gaping open to the sky. Dick's was one of the cldest places of pub- lic resort in London, for it is said to date from 1680, when coffee houses filled the Places of the more gorgeous clubs of to- day. Many generations of literary men and politicians, including, of course, Dr. John- son and Oliver Goldsmith, have in times Past dined there. Of late years much of its quaintness has been lost, and an aspect of second or third rate modernity has done much to chase away the literary ghosts who were supposed to people it. For those, however, to whom the creations of the noy- elist’s brain are a little more real and love- able than“creatures of actual flesh and tlood, Dick's will always be dear, for here it was that, on a memorable occasion, as lovers of Thackeray's “Pendennis” wili not need to be reminded, John Finucane, esq., of the Upper Temple; Mr. Bungay, the publisher, and Mr. Trotter, Bungay’s reader and literary man of business, dined together when discussing the prospects of the proposed Pall Mall Gazette, which was afterward to afford Mr. Arthur Pendennis the means of acquiring fame and moderate fortune. It was then and there that Bun- gay, after the dinner and a second round of brandy and water, was so. overcome by the prospect which the silver-tongued John Finucane and the projected paper opened up before him that he insisted upon pay- ing the bill, and actually gave James, the waiter, eighteen pence for himself. As a matter of fact, the window of this room looked out upon the entrance to Thacke- Tay’s own chambers in the temple, and the great novelist himself must have often dined in the dingy room which he made the meeting place of the characters which were the offspring of his genius. Now the room itself has followed the novelist into An Englishman's Opinion of Wash ington as a Capital. LONDON, HE SAYS, 18 PROVINCIAL European Cities Are Too Old for Real Symmetry. HIGH PRAISE FOR CHICAGO G. W. Steevens in the London Daily Mail. London's children—such of them as have not sharpened their impulse to comparison by travel among other capitals—are wont to conceive of their mother city as hideous, but monstrously impressive. Those who have traveled and compared will usually tell you the exact opposite. A few £0 Mr. Grant Allen labeled London “a squalid village,” and instituted an come parison, to London's humiliation, with— Brussels. It was hard to bear, but ft wag largely true. Where Mr. Grant Allen wag unjust, if I reme r him right, was in denying London, mot only form and comeli+ ness, but bea altogeth, I should urge &gainst him that London is the most be tiful and at the same time the most pro- vincial, of all the capital cities of the Some capitals were born; some were made; London grew. In the task of look- ing like capl the cities which we e born ivanta a city : unity of plane, the impression of sts completeness. yu see it h would lez t it, in th Washington is the bi who laid it off, 2s their is, put the Capitol on an middle, and grouped everyth metrically round it. The streets ranged in the national gridiron, Capitol as center; the } on layers-off of Sait Lake City did the same with their temple. In Washington they relieved the monotony of this plan by broad avenues cutting the gridiron dia shington is a complete maily ani one ic whole of Sophocles or a symphony of Mozart. All the parts relate one to an- other. Washington has grown out of its compl symmetry, it is true; it has sfread, as cities will, more on one side than on another. But it remains a coherent whole; when you are in one part you carry the locality of all other parts in your head, and all its architectural jewels are present= ed in the openest and most advantageous setting. Lack Deliberate Symmetry. The European capitals are too old for this deliberate symmetry. Mostly they come in- to the class of cities that were made. Paris was carved into cohesion by Haussmann, with its circle of boulevards and system of avenues. Chicago, which is really a cap- ital also, is following the example with a difference: the magnificent avenues and gardens on the blue sea front of Lake Michigan are at its base, and it has bute tressed its ring of boulevards with noble parks, Vienna transformed itself from a cramp- ed mediaeval town to a capital by leveling its fortifications into the riug—a circlet of palaces and parliaments, museums, gal- leries and courts, opera and university, without an equal for imperial stateliness. Other cities, less successful in grouping their features, have aligned themseives aiong a great street. Unter den Linden is one example, With two palaces, two mu- seums, opera and university and a dozen statues in a length of a mile, with a trium- phal arch at one end and a square with palace, gallery and cathedral at the other, The Rue Royale, at Brussels, is another— lined with public buildings, with a panor- ama of the whole city breaking away from one side and the elephantine palace of jus- tice blocking it at the end. Lo is Disappointing. After all these take the night boat home and run in at a sunshiny dawn upon our dear London. You will ha n nothing in all your journeying more utiful than the morning sheen, half mist, half smoke, that gilds the endless ocean of roofs so tenderly. But when you sei yourself down at Charing-crcss, our dear London does not look like a capital. You are in the heart of it; what do you see? There is Nelson welcoming you back, certainly—he, too, you recall, was seasick on a small boat—and ul ational Gallery. But the gov ent Offices are best seen from St. James’ Park, and the royal palaces, dotted about by themselves, are best not seen at all; the cathedral is a couple of miles away, look- ing out on to the narrow alleys of Chea si and Ludgate-hill, as the Pal of Justice coops in the narrow alley of Fleet et; the Opera is tucked up in a vege- le market, and, fo: matter, is not open; the houses of parliament are in a corner to themsel! carefully post where they destroy the v of Wes minster Abbey; the abbey fortified 1 one visible side with absurd St. Margare the university has no students and the municipal buildings do not 1 pretend to exist at ail. Poor London! It has no center and no whole. hape; it is all parts ard no The Summary of a The best way to impress a foreign visitor to London is to take him to the front of the Royal Exchange, tell him that the Mansion Hou arit hool and the Bar a ors’ prison—he will re: sehoods—and divert his attention to the pe boiling whirlpool of men is th of London. And, after s it is men that make a great ci »» yet not in all; else Ep- som Downs on Derby day is a great cit A capital, to strike the eye to the imagination, ought vi cinctly to summarize the w a nation. Vienna does’ this in w round the ring. There is the emperor, imperial family, the great nobles, Au drama and music and painting, the Semitic question, the question of Germ vs. Slay, the Catholic Church, and ihe stock exchange—all rv concretely in architecture. You may sea London till your legs ache for any such sumiaury of England, not to speak of the British empire, in a walk of an hour. Lon- don not only fails to look national; it goes out of its way to lock provincial. London is my native city, and I love every smut of it. It has the gift of an air which manties it twice daily in match- less beauty. It has a river which is tru! a living river—not a carefully-preserved ditch like the Spree or Wien, or a toy like the Seine—but a highway of ships and a vista of endless mystery and grandeur. Steam up it at evening in the red eye of the sun, see the smoky majesty of London rise luridly up to heaven, and you never call it anything but the most derful and awful of all cities. It is re the heart of the world. But inside it not look it. “I have come,” said the young man, “to ask for your duughter’s hand.” The proud banker gazed over his glasses at the fellow and demanded: “Well, have you any means of supporting ner?” “Alas! I am poor—but hear my story.” “Go on!” “When I spoke to Claudia about com- ing to see you, she told me it was useless ~that her mother was the man of the house, and that I had better go to: her. But I said: “No! Your father may permit your mother to think that is the man of the house, just to humor