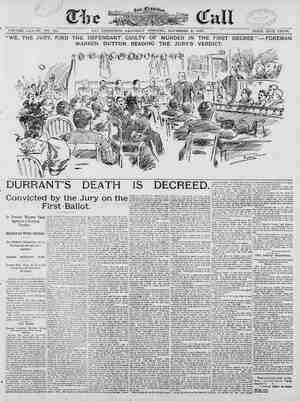

Evening Star Newspaper, November 2, 1895, Page 18

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

18 : 2, 1895-TWENTY PAGES. THE EVENING STAR, SATURDAY, NOVEM! E? UNCLE JOHN AND THE RUBIES, BY ANTHONY HOPE, Author of “The Prisoner of Zenda,” “The Dolly Dialogues,” &c ee i (Copyright, 1805, by A. H. Hawkins.) There may still be some very old men about town who remember the duel be- tween Sir George Marston and Col. Merri- dew; there may still be a venerable lawyer or two who recollect the celebrated case of Merridew against Marston. With these ex- ceptions the story probably survives only in the two families interested in the mat- ter and in tne neighbohood where both the gentlemen concerned lived, and where thelr successors flourish to this day. The whole affair, of which the duel was the first stage and the lawsuit the second, arose out of the disappearance of the Maharajah’s ru- bies. Sir George and the colonel had both spent mary years in India, Sir George oc- cupying various imporfant positions in the company’s service, the colonel seeking for- tune on his own account. Chance had brought them together at the court of the Maharajah of Nuggetabad, and they had struck up a friendship, tempered by jeal- ousy. The Maharajah favored both; we Merridews maintained that Uncie John was first favorite, but the Marstons declared that Sir George beat him; and I am bound to admit that they had a plausible ground for their contention, since, when both gen- tlemen wre returning to England, the Maharajah presented to Sir George the six magnificent stones which Lecame famous as the Maharajah’s rubies, while Uncle Jchn had to content himself with a couple of fine diamonds. The Maharajah couli not have expressed his preference more ignificantly; both his friends were passion- ste lovers of jewels, and understood very well the value of their respective presents. Uncle John faced the situation boldly, and declared that he had refused the rubies; we, his family, dutifully accepted his ver- sion, and were in the habit of laying grea stress on his conscientiousness, The Mar stons treated this tradition of ours with open incredulity. Whatever the truth was the Maharajah’s action preduced no imme diate breach between the colonel and George. They left court together, arrived together at the port of Calcutta, and came home together round the cape. The trou- ble began only when Sir George discovered, at the moment when he was leaving the ship, that he had lost the rubies. By this time Uncle John, who had disembarked a few hours earlier, was already at home dis- playing his di: monds to the relatives who had assembled to greet him. Into the midst of this family gathering there burst the next day the angrwiorm of Sir George Marston. He had driven post- haste to his own house, which lay some ten miles from the colonel's, and had now ridden over at a gallop: and there before the whole company he charged Uncle John with having stolen the Maharajah’s rubies. The colonel, he said, was the only man on board who knew that he had the rubies or where the rubies were, and the only man who had enjoyed constant and unre- stricted access to the cabin In which they were hidden. Moreover, so Sir George de- clared, the colonel loved jewels more than honor, honesty, or salvation. The colonel’s arswer was @ cut with his riding whip. A challenge followed from Sir George. The dvel was fought, and Sir George got a ball in his arm. As soon as he was well my uncle, who had been the challenged party in the first encounter, saw his seconds to arrrange another meeting. The cut with the whip was disposed of; the accusation remained. But Sir G ge refused to go out, declaring that the dock, and not the field of honor, was the proper place for Col. Merridew. Uncle John, being denied the remedy of a gentleman, carried the case into the courts, although not into the court which Sir George had indicated. An action of slander was entered and tried. Uncle John filled town and country with his complaints. He implored all and sundry to search him, to search his house, to search his park, to search everythin chable. A number of gentlemen form- ed themselves into a-jury and did as h asked, Uncle John himself superintendin their labors. ‘0 trace of the rubies was found. George was unconvinced: the action went on, the jury gave the colonel £5,000; the eolonel ga’ the money to c¢! ty, and Sir George Marston. mounting hi horse eutside Westminster Hall, observed, loud! , he stole them all the same! With this the story ended for the outer worl! People were puzzled for a while, and then forgot the whole affair. But the Marstons did not forget it, and would not be consoled for the loss of their rubies. Neither did we, the Merridews, forget. We were very proud of our family honor, and we made a point of being proud of the colonel also, in spite of certain dubious stories which hung about his name. ‘The feud persisted in all its bitternes: We hurled scorn at ope another across the space that divided us; we were absolute strargers when we mt on private ov sions. My father, who succeeded his uncle, the colonel, was a thorough-going atthe of his predecessor. Sir George's son, Sir Matthew, openly espoused his father's cause and accusation. Meanwhile no hu- man eye had seeu.the Maharajah’s rubie from the hour at which they had disap peared from the cabin: of the East India- man Elephant. A train of cirecimstances now began which bade fair to repeat the moving trage- dy of Verona In one corner of the world, L toyself being cast for the part of Romeo. As I was following the hounds one day, I came upon a young laly who had suffered a fall, fortunately without personal injury, and was vainly pursuing her horse across a sticky plough. I canght the horse and led him to his mistress. To my surprise, I d myself In the presence of Miss Syl- via Marston, who had walked by me with a stony face half a hundred times at county balls and such like social gatherings. She drew back with a sort of horror on her ex- tremely pretty face. I dismounted and stood ready to help her into the saddle. “My groom is somewhere,” said she, looke ing around the landscape. “Anyhow, I didn’t steal the rubies,” said I. The truth that in each of the half hundred occasions I have referred to I had tted that the feud forbade acquaint- ston and myself. I and T were concerned. My remark produced an extremely haugh- ty expression on the lady's fac 1 stood patiently by the horses. The absurdity of the position at last struck my companion; she uccepted my istan although grudging I mourted MW haste a ror fe her, We we trast eat She Watched Him Fix the Saddle. the run, and Miss Marston turned home- ward. I did the same. For two or three miles: way would be the same, For some minutes we were silent. Then Mi Marston observed, with a long glance “L wonder you Can Le so obstinate about them. “The verdict of the jury—" I began. “Oh, do Iet the jury alone,” she inter- rupted, impatiently. I tried another tack. “I saw you at the ball the other night,” [ remarked. id you? I didn’t s percetved vineced of that.” “Well, then, I did see you, but how coul. I—well, you know, papa was at my elbo: I was encourazed by this speech, aii quite reasonably. “It's a horrid bore, isn’t it?” I venture! to suggest. “What?” e you.” that you were quite con “Why, the feud.” “on! After this there was silence again till we reached ihe spot where our roads diverged. I reined up my horse and lifted my hat. Miss Marston looked up suddenly. “Thank you so much. Yes, it is rather @ bore, isn’t it?” And with a little laugh anda little blush, she trotted off. More- Cver, she looked over her shoulder once be- fore a turn of the read hid her from sight. “It's a confounded bore,” said I to my- self as I rode away alone. My father was a very firm man. T am not Sir Matthew Marston's son, and I do not scruple to describe him as an obstinate man. in this world the people who say Ss” generally beat the people who say “no’’—hence comes progress or de- cadence, which you will—and although both Sir Matthew and my father insisted that the acquaintance between Miss Marston and myself should not continue, the ac- quaintance did continue. We met out hunting, and also when we were not hunt- ing anything except one another. he truth is that we had laid our heads to- gether (only metaphorically, I am sorry to say), and determined that the moment for an amnesty had arrived. It was forty years or more since the colonel had, or had not, stolen the Maharajah’s rubles. Many suns had gone down on the wrath of both fam- ilies. A treaty-must be made. The Mars- tons must agree to say no more about the crime, the Merridews must consent to for- give the false accusation. The Maharajah’ rubies had vanished from the earth; their evil deeds must ‘e after them no longer. Sylvia and I agreed on all these points one morning in the woods among the prim- roses. “Of course, though, the colonel took them,” said Sylv by way of closing the discussion. Nofhing of the sort,” said I, rather em- phatically. Sylvia sprang away from me; a beautiful, stormy color flooded her cheeks. “You say,” she exclaimed indignantly, that you—that you—that you—that you— well, thot you care for me, and yet—” “The colonel certainly took them,” I cried hastily. “Of course he did,” sald Sylvia, with a radiant smile. ssumed a m You + aggrieved expression. id 1, plaintively. “to “IF TO BE clined to find a new insult in it, and I naa | “My dear sir, I ask no better,” cried Sir great difficulty in bringing him to a more reasonable view. His suggestion at last was—and I could obtain no better terms from him—that, Sir Matthew should admit that nothing had occurred to suggest Col. Merridew’s guilt, but that at the same time it was c-nceivable that a sane man might hive thouzht Col. Merrdew guilty. When I’next met Sylvia 1 communicated my father’s suggested modification of the terms of peace. I explained that it covered a real and most material concession. “Papa will never asree to that,” sald she sorrowfully, and no more he did. Negotiations and pourparlers continued. Sylvia grew thinner. I became absent and distrait in manner. After a month Sir Matthew forwarded fresh terms. They were as follows: Although Col. Merridew may not haye stolen the Maharajah’s rubles, yet every reasonable man would naturally have concluded that he had stolen the rubies.” My father objected to this and proposed to substitute “Although Col. Mer- ridew did not steal the Maharajah’s rubies, yet a reasonable man might not impossibly think that he had stolen the rubies. 5 Sylvia and I built hopes on this last for- mula, but Sir Matthew unhappily objected to it. Matters came to a standstill again and no progress was made until the vicar, having heard of the matter (indeed by now it was common property and excited great interest in the neighborhood), offered his services as mediator. He said that he was a peacemaker by virtue of his office and that he hoped to be able to draw up a statement of the case which would be palatable to both parties. Sir Matthew and my father gladly accepted his friendly offices, and the vicar withdrew to elaborate his etrenicon. ‘The vicar was a man of great intellectual subtlety, which he found very few oppor- tunities of exercising. Therefore he enjoy- ed his new function extremely, and was very busy riding to and fro between our house and the Marstons. Sylyia and I grew im- patient, but the vicar assured us that the result of hurrying matters would be an ir- table rupture. We were obliged to submit, and waited as resignedly as we could until the terms of peace should be finally settled. At last the welcome news came that the vicar, lying “awake” on Sun- day night, had suddenly struck on a form of words to which both parties could subscribe with satisfaction and without loss of self- AN EXPERT THIE have—to have—to have— pity on me, and yet “He didn't take them!” cried Sylvia, im- pulsively. That matter seemed satisfactorily, and we “How dare I tell pa nsively. “Well, I shall have a row with the gov- ernor,”’ I reflected, ruefully “Horrid old rw sh they were at the bottom of the sea!” said Sylvia. wish they were round your neck, vell, to have some to be settled quite ean you, Mr. Merridew?" mur- aA great deal more than But she would not let me. ent home from this inte ay that,” I cried. Now, as Iw os I was, I protest, filled with regrets that the Mahar: rubles could not adorn and be adorned by Sylvia's neck than with apprehensions as to the effect my communication might have upon my father. Whether Col. Mefridew had stolen them or not became a subordinate q reat problem was, where not round Syl less acute the emotion that y years before. I was so engressed with this aspect of the that, as my father and I cigarettes after dinner, 1 exclaimed inad- vertently “How splendidly they'd have suited her, “they” or “them,” without further identif- cation, he understced to refer to the Jahara, 's rubies. “Who would they have suited?” asked my father. “Why, Sylvia Marston,” I sid. When you have an awkward disclosure to make, there is nothing like commiiting yourself to it at once by an irremediable discretion. It blocks the ba and clears the way forward. My yivia Marston defined the position with lute clearness. p What's Sylvia Marston to you?” asked my father. scornfully. “The whole world, and more,” I answer- ed fervently. My father rang the bell for coffee. it had been served he remarked: “IT think you had better take a run on the continent for a few months. Or what do you say to India? My Uncle John—* nd you, I don’t believe he took them,” I interrupted. “If you did, T shouldn't be sitting at the me table with you,” observed my father. “But she’s the most charming girl 1 ever 1 remarked, returning to the real When follow the connection of your thoughts,” said my father. There are one or two points that deserve mention here. The Marston property was 4 very nice one; combined with ours, it vould make a first-class estate. Sir Mat- thew had no son, and Sylvia was his only daughter; to be perpetually opposed in everything by a neighbor is vexatious; my father was not reaily a convinced home ruler, and had only appeared on platforms in that interest because Sir George was such a strong unionist. Finally,the duches had said that his patience was exhauste with the squabbles of the Merridews and the Marstons, and that for her part she wouldn't ask either of them. Now. my father cared as little for a duchess as any man alive, but the elaret at Sangblew Castle was preverbial. “If,” said my father at the end of a long dis nm, “the man (he meant Sir Mat- the’ arston) will make an absolute and unreserved apology, and withdraw all tm putations on Uncle John’s memory, I shall be willing to consider the matter.” “You might as well,” I protested, “ask him to eat the rubies. “TI believe old Sir George did,” answered ny father er'mly. I must pass over the next two or three months briefly. Thwarted love ran its usual course. Sylvia (whose interview with Sir Matthew had be-n even more uncom- fortibie than mine with my father) peaked and p.n-d and was sent to stay with an aunt at Cheltenham; she returned worse than ever. I went to Paris, where I en- yed myself very well, but I came back . _Sylv health was gravely eed. I displayed an alarming ina- se tie down to anything. We used meet covery day in highest exultation, “ni pirt every day In deepest woe. We talked of dexth and elopement alternately, and treated our fathers with despairing and most exasperating dutfulness. The month of June found ourselves and our af- fections exactly where we and they had been in March, A daughter is, I take it, harder to resist than a son. It was for this reason and not because Sir Matthew was in any degree less stubborn than my father that the first overtures came from the Marstons. Sylvia was brimming over with delight she met me one morning. w pa is ready to be reconciled.” she cre’. “Oh, Jack, isn’t it delightful “What? Will he apologize?” I asked, eae ly, as I caught her hand. said she, with smiling lps and dancing eyes. “He'll admit that nothing has oecurred to prove Col. Merridew’s ilt, if your father will admit that every te 4. must have thought that Col. Merridew was guilty.’ “Hum,” said I doubtfully. fither,” My father received my report in a some- what hostile spirit. At first he was in- “Tl tell my of personal loss, | rston post haste | t over our | in our family spoke of | r before break- ig. He gr do me respect. I called on the fast on Monday mori with evident pleasure. x * said he, rubbing his hands con- iy, “I think I have managed it this and he hummed a light-hearted tune. ‘What is the form of statemen la ‘or I could scar: ve in the go answered the vicar: ‘ ‘Al- S n whatsoever to think that Col. ridew stole the Mahara- jah’s rub‘es, yet any gentleman may well ave eat and had every reason for at Col. Merridew did steal the s rubies.’ "” seems € ery fair and said I, after a moment's consideration. I think so, my dear young friend,” said » vicar, comy “T imagine that it an end to all trouble between your equal,” thy father and Str atthew."” “I'm sure it mi greed. “I have modeled it,” pursued the -v icar, holding out the piece of before him | and regarding it loving! the form of it on—* “On the thirty-nine article thoughtlessly, tat all,” sa‘d the vies par mentary apologie: As may be supp: of feverish suspens T have modeled I suggested, arply. “On and I spent a » mt gated only by nother's compan. The ar rode first fatthew he reached there atvhalf- » and remamed to luncheon, Start- ing again at % (evidentlySir Matthew h: 1 my fathe bohm tll Ivia about 6 1 came to d-nner. My father was then I looked at him, but had not e to ask him any questions. Present he came and patted me on®€he shoulder. ‘I have made a great sacrifice for your sake, my boy,” said he. “Sir Matthew Mar- ston and his daughter will dine here tomor- row.” And he flung himself into a cha‘r. “Hurrah!” I cried, springing to my feet. “The vicar is coming also,” pursued my ‘ather, with a sigh; and he looked up at Unele John’s portrait, which hung over the mantelpiece. “I Fope I have not done wrong,” he added, seeming to ask the col- onel’s pardon in case any slight had been put upon his hallowed memory. The colonef smiled down upon us peacefully, seeming to enjoy the prospect of the glass of wine which he held between his fingers and was represented as being about to drink. “It's a wonderfully characteristic portra of dear old Uncle John,” said my father sighing again. i Now, reconciliations are extremely whole- some and desirable things; in this case, in- deed, 4 reconciliation was an absolutely es- sential and necessary thing, since the hap- piness of Sylvia and myself entirely de- pended upon it, but it cannot, in my opin- ion, be maintained that they ‘are in them- selves cheerful functions. After all, they are funerals of quarrels, and men love their quarrels. The dinner held to seal the peace between Sir Matthew and my father was not enjoyable, considered purely as an en- tertainment. Both gentlemen were stiff and distant; Sylvia was shy, I embarrassed: the vicar bore the whole brunt of conversatign. In fact, there were great difficulties. It wag impossile to touch on the subject of the Maharajeh's rubies, and yet we were ali thinking’ of the rubies and of nothing else. At last my father, in despair, took the bull by the horns. He was always in favor of a bold course, as Uncle John hag been, he said. ‘ “Over the mantelpiece,” said he, turning to his guest with a rather forced smile, “you will observe, Sir Matthew, a portrait of the late Col. Merridew. It is considered an extremely good likeness,” Sir Matthew examined the colonel through his eyeglasses with a critical stare, “It looks,” said he, “very like what I have always supposed Col. Merridew to have been, indeed, exactly like.” My father frowned heavily. Sir Mat- thew’s speech was open to unfavorable in- terpretation. “You mean,” int21posed the vicar, “a man of courage and decision? Yes, yes, indeed, the facé looks like the face of just such a man. “Poor Uncle John,” sighed my father. “His last years were embittered by the un- founded aspersions—”" “f beg your pardon, politely but stiflly. “By the unfounded but very natural ac- cusations,” suggested the vicar hastily. “To which he was subjected,” pursued my father. “Or—er—may we not say, exposed him- self?” asked Sir Matthew. “In fact, which were brought against him—wrongly but most naturally,” suggest- ed the vicar. Matters looked as unpromising as they well could, Sylvia was on the point of bursting into tears, and my thoughts had again turned to an elopement. My father rose suddenly and held out his hand to Sir Matthew. Again he had decided on the bold course. “Let us say no more about it,” he cried generously. “With all my heart,” cried Sir Matthew, springing up and gripping his hand. ‘The vicar’s eyes beamed through his spectacles. I believe that I touched Sylvia's foot under the table. “We will,” pursued my father, “remem- ber only one thing about the colonel. And that is that one bottle remains of the fa- mcus old pipe of port that he laid down. In that, Sir Matthew, let us bury all un- kindness. been hard to move) h at and was said Sir Matthew, my father w: Matthew. z The heavens brightened—or was it Syl- via's eyes? The tler alone looked per- turbed; three butlers had lost their situa- tions in our hous¢ghold for handling the colonel’s port in a manner that lacked heart and tenderness. “I/cannot bear a callous butler,” my father d to say. “Fetch,” said my, father, “the last bottle of the colonel’s pdft, a decanter, a cork- screw, a funnel, a piece of muslin and a napkin. I will decapt Sir Matthew's wine myself.”” Z “Sir Matthew's wine!” Could there have been a more delicatg compliment? ‘The colonel,” my yatner continued, “‘pur- chased this wine himself, brought it home himself, and, I belleye, bottled a large por- tion of it with his gwn hands.” “He could not have been better employed,” said Sir Matthew,, ¢prdially. But I think there was a latent hint that the colonel had sometimes been much worse employed. Dawson appeared with the bottle. He car- ried it gs though ft had been a baby, com- bining the love of a mother, the pride of a nurse, and the uneasy care of a bachelor. “You have not shaken it?” asked my father. “Upon my word, no, sir,” answered Daw- son, earnestly. The poor man had a wife and family. My father gripped the bottle delicately with the napkin and examined the point of the corkscrew. “Tt would be a great pit ely, “If anything happened to he observed, the Nothing happened to the cork. With in- finite delicacy my father persuaded it to leave the neck of the bottle. Sir Matthew = ready with decanter, funnel and mus- in. We must take care of the crust,” re- marked my father, and we all nodded sol- emnly. My father cast his eyes up to Uncle John’s pertrait for an instant, much as ff he were asking the old gentleman's benediction, and gently inclined the bottte toward the mus- lin-covered mouth of the funnel. f only my poor uncle could be here,” he sighed. Uncle John had been very fond of port. “I should be delighted to meet him!” cried Sir Matthew, in genuine friendliness. The vicar took off his spectacles, wiped them, and replaced them. My father tilted the hottle a little more toward the funnel. Then he stopped suddenly, and a strange, puzzled look appeared on his face. He looked at Sir Matthew, and Sir Matthew looked at him, and we all looked at the hottle. “Does old port wine generally make that noise?” asked Sylvia. For a most mysterious sound had pro- ceeded from the inside of the bottle, as my father carefully inclined it toward the fun- nel. It sounded as if—but it was absurd to suppose that a handful of marbles could uave found their way into a bottle of old “The crust—,” began the vicar, cheer- full, “It's not the crust,” said my father, de- cisively. “Let us see what it is,” suggested Sir tthew, very urbanely. “I've done nothing to the bottle, sir,” cried Dawson. My father cleared his throat and gave the bottle a further inclination toward the funnel. A little wine trickled out and found its way (through the muslin. My father smelt the muslin anxioi but seemed to gain no enlightenment. He poured on un- der the engrossed gaze of the whole party. ‘Phe marbles, or what they were, thumped in the bottle; and with a little jump some- thing sprang out into the muslin. Sir Mat- thew stretched out a hand. My father waved Lim away. “We will go on to the end,” said he, sol- emnly, and be took it up, the object’ that had ‘allen into the muslin, between his finger and thumb ahd placed it on his plate, t It was round in shape, the size of a very larse pill or a smallish marble, and of a dull color, like that of rusted tin. Mv father poured on,:and! by the time that the last of the wine was out no less than seven of these strarge objects lay in a neat sroup on my father’s plate, one lying by if a litle removed from the others. “I have placed t “because it is much lighter thi th amine the six firs id Sir Matthew; in a tone of suppre excitement. I, Sir Matthew,” said my fa- and hé took up one of t ther, grave six that lay in a group. said he, look round, “appears to be com- posed of tin. '¢ We all agree The surface was composed of tin; a line running down the middle where the tin had been carefully and dexterously soldered together. Sir Matthew having felt in his pocket, pro- duced a large penknife and opened a strong blade. He held out the knife toward my father, blade foremost, such was his agita- tion. “Thank you, S'! ther, in courteous and und the blade and gr: Absolute sile: * said my fa- uim Voice, reaching »ing the handl ce now fell on the compan S perfectly composed. E {creed the point of the knife into the su face of the object and made a gap; then he peeled off the surface of tin. I felt Sylvia’s eyes turn to mine, but I did not remove my gaze from my father’s plate. Five times did my father repeat his operation, placing what was left in each case on the table- cloth in front of him. When he had fi ished his task he looked up at#Sir Matthe: Sir Matthew's face bore a look of mingled bewilderment and triumph; he opened his mouth to speak; a ggsture of my father's hance imposed silenée on him, “It remains,” said my father, “to exam- ine the seventh object The seventh object was treated as its companions had been; the result was dif- ferent. From the shelter of the sealed tin covering came a small roll of paper. My father unfolded it; faded lines of writing appeared on It. “Uncle John's hand,” said my father, sol- emnly. “I propose to read what he says.” “An explanation is undoubtedly desir- able,” remarked Sir Matthew. “Aren't they beautiful?” whispered Sylvia longingly. ~ A glance from my father rebuked her; he began to read what Col. Merridew had written. Here it is “That old fool Marston, having made the life of everybody on board the ship a bur- den to them on account of his miserable rubies, and having dogged my footsteps and spied upon my actions in a most offensive manner, I determined to give him a lesson. Se I took these stones from his cabin and carried them to my house. I was about to return them when he found his way into my house and accused me—me, Col. John Merridew—of being a thief. What followed is known to my family. The result.of Sir George's intemperate behavior was to make it impossible for me to return the rubies without giving rise to an impression most injurious to my honor. I have, therefore, placed them im this bottle. They will not be discovered during my lifetime or in that of Sir George. When they are discovere I request that they may be returned to his son with my compliments and an expression of my hope that he is not such a fool as his father. JOHN MERRIDEW, Colonel.” Continued silen-e followed the reading of this document. The Maharajah’s rubies glittered and gleamed on the tablecloth. y father lookel up at Uncle John’s pic- ire. To my excited fancy the old gentle- man seemed to smile more broadly than be- fcre. My father gathered the ribies into his hand and held them out to Sir Mat- thew. Oeus You have heard Col.Merridew's message, sir, id my father. ‘There is, I presume, no need for me to repeat it. Allow me to bard you the rubies.” Sir Matthew bowed &tiffly, took the Maha- rajah’s rubies, cofinted them carefully, and dropped them one by one into his waist- ccat pocket. ss Take away that battle of port,” said my’ father. “The tn Will have ruined the “flavor.” “What shall I do with it, sir?” asked Dawson. “Whatever you,plaase,” said my father, and looking up again at Uncle John's pic- ture, he exclaimed in an admiring tone, “An uncommon man,’ indéed! How few would have contrived sq perfect a hiding place. vivia,” said Sir Matthew, “get your cloak.” Then he turned to my father and continued, “If, sir, to be an expert thief —” My father sprang to his fee Sylvia caught Sir Matthew by the arm; I was ready to throw myself between the enraged gentlemen. Unele John smiled broadly down on us. The vicar looked up with a mild smile. He had taken a nut and was in the act of cracking it. ‘Dear, dear!" said he. “What's the mat- ter?” ir Matthew Marston,” said my father, “ventures to accuse the late Col. Merridew cf theft. And that in the house which was |. Merridew’s. “Mr. Merridew,” said Sir Matthew, in a cold, sarcastic voice, “must admit that any cther explanation of the colonel’s action is—well, difficult. And that in any house, whether Col. Merridew’s or another's.” “My dear friends,” expostulated the vicar, “pray hear reason. The presence of these —er—articles in this bottle of port, taken in conjunction with the explanation afforded | the headgear. by the late Col. Merridew’s letter, makes thef whcle matter perfectly clear.’ The vicar paused, swallowed his nut, and then continued with considerable and proper pride. “In fact, although there is no rea- son whatsoever to think that Col. Merri- dew stole the Maharajah’s rubies, yet any gentleman may well suppose, and has every reason for supposing, that Col. Merridew did steal the Maharajah’s rubies.” Sir Matthew tugged at his beard, my father rubbed the side of his nose with his forefinger. The viear rose and stood be- tween them with his hands spread out and a smile of candid appeal on his face. “There is no reason at all to suppose Uncle John meant to steal them,” observed my father. “I have every reason for supposing that he meant to steal them,” said Sir Matthew. “Exactly, exactly,” murmured the vicar: yhat I say, gentlemen; just what I say.’ My father smiled; a moment later Sir Matthew smiled. My father slowly stretch- ed out his hand; Sir Matthew's hand came slowly to meet it. “That's right,” cried the vicar, approv- ingly. “I felt sure that you would beth listen to reason.” My father looked up again at Uncle John. “My uncle was a most uncommon man, Matthew,’ said he. “So I should imagine, Mr. Merridew,” an- swered Sir Matthew. “And now, papa,” said the Maharajah’s rubles.” “A moment,” said Sir Matthew; “there ee matter of £5,000."" “We cannot,” said my father, “go be- hind the verdict of the Jury” . Sir Matthew turned away and took a step toward the door. “But,” my father added, “I will settle twice the amount on my daughter-in-law.” We will say no moré about ! agreed Sir Matthew, turning back to the table. So the matter rested, and before long I saw the Maharajah’s rubies round Sylvia’s neck. But as I sit spposite the rubies and under Uncle John’s portrait, I wonder very much what the true story was: Uncle John was very fond of rubies, yet he was also very fond of a joke. Was the letter the truth? Or was it written in the hope of protecting himself in case his hiding place was by some unlikely chance discovered? Or was it to save the feelings of his de- scendants?. Or was {t to annoy Sir George Marston's descendants? I cannot arswer these questions. As the vicar says, there is no reason to suppose that Uncle John stole the rubies; yet any gentlemar. may weil suppose that he stole the rubies. Uncle John smiles piacidly down on me, with his gJass of port between his fingers, and does not solve the puzzle. He Was an uncom- mon man, Uncle John! At any rate, the vicar was very pleased with himself. ——__ THE BICYCLE NoD. What Shall Take the Place of the Conventional Sign of Recognition? From the Boston Herald. A fresh cause of complaint against the Wheelman has just been brought to the front by sticklers for outward signs of good manners. These individuals contend it is not alone the bicycle face that should be noted as an indication of degeneracy, but the painful fact that riders no longer pay prop:r deference to passing friends by lift- ing or touching the hat without danger to them:elves or others. A curt nod is about the only recognition even the Great Mogul 8 likely to receive from a gentleman speed- ing on wheel, and the effect is most dis- astrous. The general “How d’y do” is miss- ed, with the conventional raising of the hat, and the friend or the acquaintance who rushes by with his bicycle face and merely a sweeping glance your way leaves a most unpleasant impression. “What has happened to Jones? Is the baby ill? Doesn't he like us any more?’ And Jones, who is making heroic efforts to bilance the machine and keep from being run down by an etectric car, holds on to. the bir with both hands and speeds away. leay ng an impression of surliness and im- poxiteness behind him. Either people must leara to ride the bicycle with one hand, or tiers must be some arrangement by which the hat can be bobbed to one’s friends There might be a string that could be pulled by a movement of the foot, or, per- haps, the unskillful :iler could wear a p'ac- ‘d saying, “I am not b.ind; please consider I've bowed,” which would soothe the oth- s feelings, but, at all events, this cour- . demanded by etiqueite, must be pre- The outdoor world would assume sober aspect if nobody was to greet us with bright glances and cheerful tip of A boorish demeanor arouses corresponding resentment that argues adly for both parties, but when the cause is needless, it is more pity to permit it to egtend and gradually fasten among the customs of the day. If cycling has come to stay, its manners will become permanent, also. The bicycle fa we shall have al with us, but mist all the graciousness of social or busi- ness intercourse be banished on its account? Si Sylvia, “give me much Art.” From Puck. Once I wrote a tragedy "Twas a grewsome thing’ Homleide and sufeide, dd poisoning! & manager, shook his head! rit, but he said. cht I wrote a novel, then, hologiea, mystic, weird, Then T penned an epic grand; In itt ts dread, their frowsy locke— they said. ight a printer ont. 1d the whole three pi Published it in green and white, Ti the nation read, Cuties hailed it with'd ‘This ix Art!” they si ~ cee = What Gave Him Away. om the India Rubber World. A meek-looking stranger, with a distinet- ly ministerial air, applied for permission to look over a large rubber factoty. He knew nothing at all about the rubber business, he said, and, after a little hesitation, he was admitted. The superintendent showed him about in person, and the man's ques- tions and comments seemed to come from the densest ignorance. Finally, when the grinding room was reached, he lingered a little, and asked in a_ hesitating way: “Couldn't I have a specimen of that cw ious stuff for my cabinet?” “Certain! replied the superintendent, although it was a compound the secret of which was worth thousands of dollars; “certainly, cut off as much as you wish.” With eager step the visitor approached the roll of gum, took out his knife, wet the blade in his mouth, and—‘“Stop right where you are!” said the superintendeni, laying a heavy hand upon the stranger; “you are a fraud and a thief. You didn’t Jearn in a pulpit that a dry knife won't cut rubber.’ So saying, ne showed the impostor to the docr, and the secret was still safe. ———_-+0+—____ Adding Insult to Injury. From the Troy Times. An Oregon newspaper thinks it has dis- covered an instance of the crowning act in the degradation of the horse by the bicycle. A man in Dallas owns a horse and also a bicycle, and the bicycle is the latest Jove. For it he has neglected his horse until the latter has grown fat and lazy for want of exercise. His stableman said the horse really must have exercise, so the owner ties it by a long halter to the handle of his bicycle and trundles along three or four miles a day, leading the horse ignomin- iously behind him. F —s Highest of all in Leavening Power.— Latest U.S. Gov’t Report Ro al Baking Powder ABSOLUTELY PURE NEW PUBLICATIONS. PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE OF FINANCE. A Practical Guide for Bankers, Merchants and Lawyers, Together with a Summary of the Na- tional and State Banking Laws and the Legal Rates of: Interest, Tables of Foreign Coins and a Glossary of Commercial and Financial Terns. By Edward Carroll, jr. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. In these days when financial questions are such frequent topics for political dis- cussion, a work of this sort, dealing in a plain manner with the principles of money and commerce, has unquestionably a prom- ising future. There is no scarcity of works on political economy, but they are not modern, and Mr. Carroll has in this volume brought the principles of that somewhat obstruse science into the latter day form that is very readable. His appendix of tabulated facts and a glossary of terms are valuabe additions to the work. BEAUTIFUL BRITAIN. The Scenery and Splendors of the United Kingdom, Royal Residences, Homes of Princes and Notlemen, Palaces, Cas- tles and Stately Houses, Beauties of Mountain, Lake and River. New York: The Werner Co. This is a gorgeous work, being one of the finest books of scenery ever published. The photographs that embellish it, nearly two hundred in number, were taken by permis- sion of Queen Victoria and the titled own- ers of the historic places that are depicted on every other page. Accompanying each illustration is a well-written bit of descrip- tive text, and the work forms one of the most compiete and artistic guides to Great Britain and souvenirs of a visit to that country to be obtained from any source. WASHINGTON IN LINCOLN’S TIME. By Noah Brooks, author of american Statesmen” and “Abraham Lincoln and the Downfall of Ameri- can Slavery.” New York: The Century Co. Washington: Robert Beall. ‘To Washingtonians Mr. Brooks’ book, which is the result of his personal observa- tions in the national capital during the civil war, will be of unusual interest. It is in reality a history of the conduct of the war at headquarters from the point o! view of an active and interested onlooker Its particular value is Its plain and simpl style, that commends it to the use anc study of young people. THE ART OF LIVING LONG AND HAPPILY. Henry Hardwicke, author of “The Art of Wi ning Cases, or Modern Advocacy.” New Yor! G. P. Putuam's Sons. Washington: Woodward & Lothrop. Mr. Hardwick has in this a harder tasi than his former one of dealing with a lega: subject, as the rules of happiness are a: many and varied es the numbers of me: and women, However, the subject 1s at- tacked. vith spirit and treated with ai »bundance of matter. No man can tell an other man how to be happy with certainty of successful achievement, but Mr. Hard wicke has at least produced an ipterestins work. OTJER TIMES AND OTHER SEASONS. By Lau- rence Hutton. New York: Harper & Brothers. Washington: Woodward & Lothrop. This is another budget of Mr. Hutto! charming essays, ranging from the spor to a discourse on Christmas. The style piquant and the matter is nourishing. Th beck is a compilation, in dainty style, © Mr. Hutton's Harper's Week!y papers. A LIFE OF CHRIST FOR YOUNG PEOPLE. ~ Questions und Answers. Mary Hasti Foote. New York: Harper & Brothers. Wasi ington: Woodward & Lothrop. A book that religious teachers will fine useful. It is an expanded catechism, an. its questions and answers are clearly se iccted and arranged. SKEPTICISM ASSAILED; or, The Stronghold of lity Overturned.” Being a Powerful Rep reseutation of the Divinity of Christ and th e ‘Truth of the Holy Scriptures. 1) tton H. Tutor of the New York Bar, Yo Which, is Added Lord Lyttelton’s Famous “Tree tise on the Conversion of St. Paul. Introduction Dr. Charles H." Parkhurst of New Philadelphia: Syndicate Pablishing Co. DW ds A Story of Napoleonic Complication Orleans and Bourbonic Complication Enta ments: 4 Romance of the Pyrenees and Can- tabrian Mountains of Spain, the Mountains oi Darang Mexico, the Grand Canon Kio Colorado, King’s Kiver Canon and Yosemite Valley, Cali fornia, and Yellowstoue—now National "Pars. By Frederick A. Randie. w. New York: G. Dillingbam. Washington: Brentano's. A SET OF ROGUES, THEIR WICKED CONSPL RACY a ecount of Their Travels and Adventur with Many Other Sur Lady Biddy e.' “The Great York: MucMillan & Co. Brentano's. MYSORE. A ahib. By ¢ author of y in india, » Briton, wHeld| Fast’ for | England, Name and Fame," &e. With illustrations by W. iH. Marget and a map. New York: Charles cribne ons. Washington: Brentano's. REPORT OF THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM, Under the Direction of the Smithsonian Insti tution, for the year ending June 30, 1803. An- nual Report of the Bow ts Of the Smithsonian Institution, sho ations, Expenditures and Condit for the year ending June 30, ton: Government Printing Office. CORMORANT ‘CRAG. A Tale of the Smuggling Days. By Geo. Manville Fenn, author of “First in the e | Young, Grand Cha “rystal Hunters, lens Volens, trated by W. Rainey. New Yor & Co. {tution G REPORTER. A Story of Printiag sy, William Drysdale, author 0: “in Sun Lands," “Pro verbs From Plymeuth Puipit cte. Illustrated wharles Copeland. Boston: W. A. Wilde & ‘ OF GOLD; or, In Crannied Rocks. A ‘s Tale of Adventure on the Y st of Ireland. By Standish © nd His Compan! &e. ‘Coming Dodd, Mead & of Cuculain, °E OF THE SOUL. A Scientific Demonstra- the Existence of the Soul of Man as His Individuality Independently of the the Continulty of Life y of Spirit Return, “By Loren Albert Sherman. “Port Huron: The Sherman Co. AT WAR WITH PONTIAC; Or, The Totem of the Bear. A Tale of Kedcoat™ and Kedskin. By Kirk Munroe, vathor of “The White Conquer- ors,” &c. Tilustrated by J. Finnemore. New York: Charles Scribner's “Sops. Wasbingtou: Brentano's. THE HOUSING Eighth Labor. OF THE WORKING PEOPLE, Special Keport of the Commissioner of Prepared under the direction of Carroll . ommissioner of Labor, by EB. . L. Gould, Government Print ing Oitice. Ph.D. Washington: With Six Mustrations by New York: E. P. Datton & Wm. Ballantyne & Sons. AILLES, By Elizabeth thor of “*Wiieh Winnie,” Mystery,” “Witch Winnie in With Numerous Illustrations, New Dodd, Mead & Co. ‘i ROGER THE RANGER: A Story of Border Lit By abeth FLT 1 sie tthe World's Fair,” &c. New York: Dodd, Mead & A SHERBURNE ROMANCE. By Amanda M. Doug- 1 Sherburne House, sherburne Cousins, 3 ete. New York: Dodd, purne, Rose Time,” ART) |, Mead. —— | under Napoleon. By Albert Pulitzer. Trang« lated from the French by Mrs, B. M, Sherma 3a two Volumes. New York: Dodd, Mead & ABRAIAM LINCOLN’S SPEECHES, Compiled by, L. E. Chittenden, ex-Secretary of the UTS author of “President Lincoln,” “Personal Rem= iniscences,”” &c. New York: ' Dodd, Mead & Co. OUT OF INDIA. Things I Saw, dnd Failed to 8 in ain Days and Nights at J y pore a Elsewhere. By Rudyard Kipling. ew Yorks G. W, Dillingham. Washington: | Brentano's. A SON OF THE PLAINS. Be Arthur, Pattersony author of “A Man of His Word,” ‘The Daughs ter of the Nez Perces,”” &. New York: Maca millan & Co. Washington: Brentano's. THE REVOLUTION OF 1848. By Imbert de Sainte Amand. ‘Translated by Elizabeth Gilbert Mara tin. With Portraits. New York: Charles Scribs ner's Sons. Washington: Brentano's. rER AND MAN. A Story. By Lyof Ny Tolstol. Rendered from the Russian into Eng- lish by 8. Rapoport and John C. Kenworthy, New York: Thomas Y. Browell & Co. STUDY OF DEATH. By Henry Mills Alden, author of “God in His World: An Interpreta< tion.” New York: Harper & Brothers. Wash« ington: Woodward & Lothrop. CHILDREN’S STORIES IN AMERICAN LITERA» TU 1660-1860. By Henrietta Christian Wright. New York: “Charles Scribner's Sonse Washington: Brentano's. A DASH TO THE POLE. By Herbert D. Ws author of “A Republic Without a President,” “The New Senior at Andover,” &. New Yorkt Lovell, Coryell & Co. BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES FISH COMs MISSION. Vol. XIV, for 1894. Marshall Mo« Douald, Commissioner. Washington: Govern ment Printing Ouse SIR QUIXOTE OF THE MOORS. Being Some Ac- count of an Episode in the Life of the Sieur de Rohaine. By John Buchan. New Yorks Henry Holt & Co. UNC: EDINBURG. A Plantation Echo. ‘Thomas ‘Ison Page. Illustrated by B. West Clinedinst. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Washing- ton: Brentano's. ENGLISH LANDS, 1. Queen une and the George jell. New York: Charles Scribner's Sous. Washing= ton: Brentano s. THE ANNUAL STATISTICS OF MANUFACTURES. 18H. Ninth Report of the Massachusetts Bus reau of Labor. Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co. LITTLE RIVERS. A Book of Essays in Profitable Idieness. By Henry Van Dyke. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Washington: Brens tano’s. HE CARVED LIONS. By Mrs. Molesworth. Ile lustrated by L. Leslie Brooke. New Yorkt Macmillan & Co. Washington: Breutano’'s. tHE WISE WOMAN. A No By Clara Loutse Burnham. Boston: Houghton; Mitllin & Cox Washington: Wm. Ballantyne & Sons. ERNAT ELECTRIC CURRENTS. By Edwin “J. Houston, Ph.D., and A. E. Kennelly, Sc.D. New York: The W. J. Johnston Co. CHILHOWEE BOYS IN WAR TIME. By Sarah Ey Morrison, author of “Chilhowee Boys.” New York: Thomas ¥. Crowell & Co. RES: A Collection of Odd Rhymes at Odd Imes. By Geo E. Trescott. Burr Oak, Mo.: Geo. E. Trescott. CLARENCE, By Bret Harte. Miffin & Co. Wasbington: & Sous. THE VILLAGE WATCH-TOWER. By Kate Doug- las Wiggin. Boston: Houghton, Mifttin & Co. WILMO’ ‘Atey Nyne, Student and Dodd, Mead & Co. AND FLOWERS. "By Isaac Basset ww York: Home Journal Print. WITH GIRLS. By Ruth Ashmore, Charles Scribner's Sons, PIRIT OF IUDA! arus. New York: Do ead & HE WAY OF A MAID. By Katharine Tynan, New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. TRICKS OF A DRUGGIST. Prevents Slavery to Morphine by, Simple Deception. From the Chicago Triune. “A good deal is written about the im- prudence of physicians in prescribing mor- phine, but not half as much as should be,” said a veteran Wabash avenue druggist. “The slaves of that drug are on the in- rease. They have no trouble in procuring t, if they have the money to pay for it. it is a safe proposition that a large pro- yortion of morphine users, especially women, have been led into the habit by the vad judgment of their physicians. Let ne give you an instance: A woman in his neighborhood was ill with an eXceed- ngly painful disease. Her doctor wrote her a prescription containing morphine, she is a sensitive, nervous woman, of a ype common enough, and readily respond- d to medicine. I thought she was well, in course of a few days, she sent the srescription to me to be renewed. A week later it came again, and in less than a week after that the servant brought it a third time. I had her leave it and sent for the woman's husband. Why did his wife re- quire the prescription so often? I asked him. He didn’t know, but she had told him she couldn't do without it. Did he know i@contained morphine. He did not, and was horror-stricken. He was confl- dent his wife was ignorant of the presence of the drug, to whose effect she was he- ginning to yield. I am satisfied also she knew nothing of it. I fixed up a litle scheme with the husband. I prepared the prescription, leaving the morphine out. It was sent back once afterward, and that was the end of it. That woman was res- cued without knowing how near she had been to slavery. “Another case: I filled a prescription for pills containing a considerable percentage ot morphine for a young married woman, She experienced the effects of the drug, not knowing what’ it was, and, of course, sent it to be renewed several times. I got hold of her husband, pledged him to aid, and substituted quinine pills. The cure was completed. “There are many other instances, how- ever where women learn the nature of the stuff they are taking, and before they, realize it are its victims.” —____+2+-____ White Pique Stock Fiom the New York Herald. ~ Women who find linen collars chafe and irritate the skin of their necks are now wearing with the Norfolk jackets and open ecllars of their cloth costumes the white pique stocks. These stocks are nothing mcre nor less than an extra long four-in- hand, which is put twice around the neck before being tied. There is a little knack in tying them, which at first is difficult, but when conquered gives delightful results and is vastly more comfortable than a stiff, high collar and tie. White ties are the best for this style, as the white against the neck is more becoming than the dark colors. Of course, these ties are not to be worn more than once, but they are so well made they can be laundered without the slightest difficulty; they need not be starched if starch is irritating to the skin, as pique or duck has so much stiffness in itself that any more is quite unnecessar, ———_-—-+e-+ Art of Expression. Frem Purch, “Doctor,” said an old lady the other day to her fam!ly physician, “can you tell me how it is that some folks are born dumb?” “Why, hem, certainly, madam,” replied the doctor. “It is owing to the fact that they come into the world without the fac- ulty of speech “Dear me!” remarked the old lady; “now, just see what it is to have a medical education. I've asked my hus- band more thin a hundred times the same thing, and all that I could get out of him was, “Because they are. Boston: Houghton, Wm. Ballantyne Laz iy Josephine He From Truth,