Evening Star Newspaper, July 20, 1895, Page 14

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

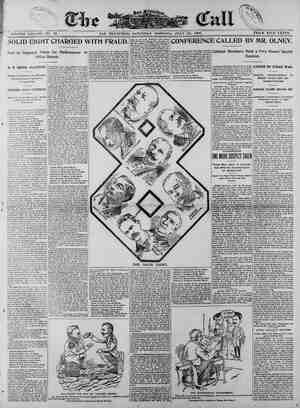

(Copyright, 1695, by Irving Bacheller.) Our train had been snowbound for near- ly two days. A‘ first most of us were very naturally restless and impatient; but as the hours drifted by we grew philosophi- cally resigned. Two of the trainmen, to- gether with several passengers, had yolun- teered to fight their way to the nearest station and bring relief; so there was noth- Dag to do but occupy our minds with cards, jonversation and smoke and try to forget ghat our stomachs had been put on short allowance. With this aim several men gathered at one end of the smoker and tock to spin- ning yarns, first humorous, ther of adven- ture, and finally drifting into what are known as “detective stories.” There were five of us ‘esides myself; two drummers, one from New York ani one from Chic: g0; & Frenchman, who bad been ‘doing’ the country; a fvesy eld gentleman on his Way east to attend his daughter’s wedding, which he was pretty reasonably sure to m's8, and a gaurt, powerfully built man, ‘with a somber, nervous face and gray hatr, who suggested a cross tetween a New York stock broker and a Kentucky colonel. The Frenchman, one of the best com- panions, by the by, I ever met, had just concluded, amid an avalancle of. weirdly accentuated English and a cyclone of ges- ticulation, a “true” story of the most pro- nounced Gaboriau type, when our somber nondescript cleared his throat. He had shown no interest whatever In the humor- ous tales of the drummers, and had paid but little more attention when the theme shifted to travel and adventure. The de- tective vein seemed, hewever, to rouse him somewhat, though hitherto he had evinced no disposition to bear his share of the telling. Therefore, when he did speak, We all turned to him with the greater rity. suppose some of you will recall the name of Jchn Phillips?’ he said, looking around. “The big detective who died a few years ago? Sure!’’ put In one of the drummers. “Yes,” ccntinved the first speaker, “the greatest, perlaps the only really great de- tective this country has ever produced.” “Let me see—but was he an American?” I asked. “It seems to me I heard once that he was an Italian.” No. His father was a Neapolitan. Se- bastian Philips—the name was originally Phillippi,” went cn the other. “Sebastian came to New York when quité young, mar- ried a southern woman and went into the business of importing fruit from Sicily. His son was born here, and when old enougn made several voyages on his fath- er’s ships. They tell how he had a quarrel with one of the captains once, deserted at Messina, and wasn’t heard of for over a year—lived amorg the peasants in the in- terior. So, you see, he was an adventur- Nothing but My Appenrance Prevented a Personal Encounter. ous young fellow, even in those days; but the experience was just what was needed to make him what he afterward became. Take the subtle intelligence of an Italian and add to it an American mother and an American education, topped off with sever- al years of life right down among the low- er classes, and you've got the best founda- tion fcr a go0d detective that I can imag- Ine. “Well, he was a good one,” interrupted drummer No. 2. “Somebody told me once— but, pardon me, sir- ‘Z “I was going to tell you of perhaps the most remarkable case that John Phillips ever unraveled,” said the somber man. “Let's have it by all means,” came from us in a chorus, in which the offending drummer joined heartily. The somber man leaned back In his seat, half closed his eyes and began: A number of years ago I was residing with an elder brother at a certain village situated on the Hudson river not far from the northern end of the Palisades. Our family was composed of my brother Rob- ert, his daughter Mary, myself and a negro servant of the name of Pompey Augustus Anderson. My brother's wife had died shortly after the birth of my niece, who was, at the time I speak of, a remarkably handsome though delicate girl. She was clever, too, and, at times, erratically bril- Mant; but she was a creature of strange moods, and there were days when she would hardly speak to any one of the household, and would either shut herself up in her room or wander off through the fields and woods, even managing to return late for meals so as to avoid sitting at table with us. My brother worried a good deal over these eccentricities; but I used to console him with the idea that young girls of from fiftzen to eighteen were apt to be dreamy and ‘morbid at times. Well, we lived in that way for upward of four years; and the only excitement that broke In on the monotony of our lives ‘was my niece's first love affair. The young man, a New Yorker, had been rusticated that fall by one of the New England col- leges which he was attending, and his family had sent him up to our village with a private tutor to spend a few weeks in study and contemplation. I never consider- ed him a positively bad fellow, but he was certainly a very lively one, and some of his escapades, of which we learned later, had been startling and original, even for a collegian. It was the most natural thing In the world that he and Mary should imagine themselves in love with each other. There was practically no masculine society for her in the village, and she was the only young woman there of refinement, beauty “My brother was found dying.” nd education. Therefore, Jack Ralph, as will call him—though that was not his eal name—spent a great deal of time at ur house. ey brother, as people are apt to do, paid MO Attention to the affair, pooh-poohed all y Warnings, and buried himself. in his coks. Then, too, he was very much ex- ee at the time over his quarrels with w railroad which Pay running its line iaightly dub two. hundred” yards rom the house. He had fought the mat- ie the court and had beaten. pute Row was as to the company’s bridging this cut, which they had agreed to do, but which they delayed so persist- ently that there seemed to be considerable malice in it. In fact, I may say all the work had been prosecuted in a most dila- tory way, and for several months we had been subjected to the annoyance of hay- ing gangs of Italians tramping around our lawns and making us feel that it was un- safe for Mary. to > out unattended. Amid such far from soothing contem- plations, my brother was dumfounded by @ point-blank request from young Ralph that he might become engaged to Mary. Then there was a scene. Robert was, I am bound to say, a selfish father, and I doubt whether itor would have been received with much favor; but he was also inclined to be puritanical in his notions, He Sat With His Head Resting Upon His Hand. and, from what he had heard of Ralph's exploits, that young man would have been the last to overcome his seifishness. There were too Many and teo plausible grounds for rational objection. If I tell you also that my brother had a violent temper, you can perhaps imagine what occurred. There was much strong language on one side and finally some flippant impudence on the other. Nothing but my appearance prevented a persoral encounter. I finally got Ralph safely out of the house; but the situation was awkward enough. He was obliged to remain in the village until re- called by his family or college, and our prospects for peace and comfort during the balance of his stay seemed poor enough. Mary was, naturally, highly indignant, and, drawing within herself, as was her habit, refused utterly to hold any but the most necessary intercourse with us or to make any promise as to not seeing her lever. Then there were more scenes— threats of personal confinement on my brother’s part, and moody, stubborn resist- ance on my niece’s. I even began to won- der whether we weren't ail a bit “‘off” by inheritance from. a great-grandmother of Robert's and mine, who was known to have been mentally unsound. Four days passed, and then a terrible event happened. My brother was found lying dead in the railway cut at the foot of the lawn, with a ragged, contused wound in his right temple and a very ex- tensive fracture of the skull. The whole village was, of course, intensely excited. Nothing so intcresting had happened there within the memory of the oldest inhabitant, and the theorists of the country store argued the matter over among themselves and with the reporters that came up from the city. There were two very decided opinions that found adherents in not un- equal force. A small majority held that my brother had gone out fcr the walk which he always took before breakfast, had fallen into the cut, and been killed. Quite a large majority, which included, however, rcost of the foreign and reportorial talent, looked mysterious and intimated that the dead man had been in a great deal of hot water, and that it was more than likely he had been knocked on the head and then thrown down the embankment. The cor- oner convened his jury of local wiseacres, and the usual inteiligent verdict was pro- pounded, to wit: That “Robert” (Smith, let us call him) “came to his death from a fracture of the skull caused by sudden contact with some dull instrument or ma- terlal.” During the twenty-four hours when all chis was transpiring I had been thinking hard, and I could not get rid of the idea that there was something wrong in the affair—something more than mere accident. At the same time I was disposed to admit to myself that my notion was based rather on intuition than on any really good rea- sons. To be sure, I had been a witness of “Fok de lawd, you doan spec’ the bitter qvarrel between my brother and Jack Ralph, but it seemed impossible to suspect the young collegian of such an act. Then, too, his attitude was the last to be adopted by a guilty man who was not also a lunatic. He went around the village an- nouncing more or less openly that he guessed the old man had been killed by some one he had insulted, and that, from his own experience, he wasn't disposed to be very hard on the party who did it. To all questions as to what his own experi- ence had been, he utterly refused to vouch- safe an answer. This was pretty nearly .enough, but when our servant, Pompey Augustus Anderson, who had been, since my brother's death, in a condition of nerv- ous excitement bordering on hysteria, went before the justice of the peace and deposed that he had overheard the quarrel between his master and Ralph, and gave its details with very reasonable accuracy, the latter ‘was prompily arrested and confined in Jus- dice Bennett's house, pending his remoyal to the county jail. Then I felt that it was time to have some detective talent superior to that of the village constable set to work on the case. I was well acquainted with the superintendent of the New York police department; in fact, I had had some in- fluence In getting him his appointment. Therefore, a telegram from me asking that he send us his best man at once was promptly honored, and, within thirty-six hours of the finding of my brother's body, John Phillips walked into the library, where I was sitting. I can remember Phillips as well as if I saw him before me now—a dark man, with straight black hair and rather beady eyes. His features were as delicate as a woman's, and his figure was small and slight—almost dapper. Only the cords that stood out in his neck and wrists went to show that he was made of tempered steel. His expression was very gtave and serious as he bowed and handed me an unsealed letter from the superintendent. It read as follow: “Dear Sir: This will introduce Mr. John Phillips, whose name is perhaps familiar to you. You are very fortunate in obtain- ing his services, as both his health and a combination of engagements and .circum- stances conspired against his taking up this case. I fave, however, felt under obligations to do my very best for you, and, at my most urgent solicitation, he has consented to waive everything and devote himself to your matter. Yours, truly, “EDWARD L. SANFORD.’ Having finished reading the above note, I shook hands with the great detective and began to express my thanks. These, however, he very quickly cut short. “You have nothing to thank me for,” he said coldly. “I am here under orders, and now, sir, pardon me if I ask you to tell me all you know of the circumstances con- nected with your brother’s death, Time is always precious, and this must excuse any apparent brusqueness on my part.” manner was ind almost repellant, but, as I looked more closely at his face, it seemed so drawn tl I was conscious of a guilty pang at ha been even in- THE EVENING STAR, SATURDAY, JULY 20, 1895-TWENTY. PAGES. directly instrumental in dragging a sick man into what bade fair to be a very ar- duous piece of work. There was nothing to do, however, but to relate, as briefly and yet as exhaustively as possible, all that I knew. . Phillips during the recital sat with his head resting upon his hand, while his eyes wandered incessantly about the apartment. He did not interrupt me once, but, when I had finished, proceeded to put his ques- ticns. Then it was that every vestige of languor vanished. His e became strangely animated, while his eyes fairly glittered. “You have been very full in everything that bears upon Mr. Ralph’s connection with the matter,” he began, “and I con- gratulate you. A professional could not have stated it more clearly. Can you tell me, though, with a little more exactness, just what you know about your brother's disputes or altercations with the Italians who were at work on the railroad cut?” “To tell the truth,” I replied, “I know very little about it. My brother always imagined that the company was trying to retaliate, by petty annoyances and de- lays in the work, for his legal opposition to their schemes. About a month ago he ceme in one morning in a towering pas- sion, cursing the whole Italian race and the foreman of this gang in particular. It appeared that he had gone down to re- monstrate with them—a proceeding which I knew he would not be apt to conduct very gently, that the foreman had been impudent and said, in effect, that the court had givon them permission and they'd do the work as they pleased and butld the bridge when they got ready. Then my brother lost his temper completely, said taat the New Orleans people were the only ones who understood how to deal with the Italian question, and that he pro- Posed to get the damned cowardly Mafia off his place, if it took a shotgun to do it. From what I gathered, very little was said in reply. Two or three of the laborers Were rather threatening,. but the foreman quieted them with a few words in Italian, and my brother rushed back to the house. I will not deny that the incident troubled me considerably for a time, though Robert laughed at my fears. Nevertheless, I took occasion to go down to the cut once or twice and talk pleasantly to the foreman. I was surprised to find him disposed to be remarkably polite, and shortly after, when the company drew the workmen off to another part of the road, he expressed his regret to me that they had not been able to complete the bridge before their de- parture. For the last two weeks none of them have been seen in the neighborhood, and my fears had entirely subsided when this terrible event happened.” “Very good,” he said, “and now may I ask y@u to summon your colored man? I believe you stated that he made the affi- davit implicating Ralph?” ‘To my surprise, I soot some difficulty in Deere the negro to tell Phillips his story. “Wha's de good, Massa Henry?” he kept repeating; and nothing but my abso- lute orders availed to bring him into the library. Once there he showed much agi- tation at first. Then he braced himself and launched out into a voluble relation of the quarrel between Halph and my brother, ending up with: “An’ I jes’ knowed dat young fellah warn’t no good from de day he done walk- ed over mah phortchallakah hed an larfed fit to kill beself when I tol’ him to be moah cahful.” “Where were you, Anderson,” asked Phil- He Pointed Toward the Left Breast. lips, quietly, “when you heard the word: between your master and Mr. Ralph?” “Tn de hall, sah.” : ‘What were you doing there—I mean, what did you go there for?” “Nuftin’ at all. I jus’ went dah t’ see 'f everything was all raht and clean an’'—" “What time of day was it?” “I doan rahtly recollec’ dat, sah.” “Your present master tells me that the dispute took place in the afternoon very shortly before dinner.” “Das raht; das raht, now.” “Yon are the only servant, I believe.” “Yessah.”” “Well, aren’t you pretty apt to be con- fined -to the kitchen just before dinner? It’s a rather bad time to go looking around the house for nothing in particular, isn't i?" Anderson's face began to grow ashy and hig legs trembled perceptibly. “Foh de Lawd, Massa Phillips,” he stam- mered. “Yo doan spec me a killin’ Massa Smith?” “Certainly I don’t, Anderson,” said Phil- lips, reassuringly; “but I do know that you have committed perjury. You didn’t see or hear the quarrel, as you said you did. ‘That's all. You can go now.” Anderson tried to reply, but seemed un- able to articulate. Then he almost reeled from the room, while I looked on in utter surprise. Phillips turned to me: ‘ou and your brother probably talked the matter over at table?’ he sald. “That's hardly likely, in the presence of my Niece. It would not have been an agreeable subject.” “Neither Is it likely that your niece was present at the meal immediately following the summary dismissal of her lover.” “That's so. She remained in her room,” I sald quickly; “and, although I can’t rec- ollect definitely, I don’t doubt that we did talk some on that occasion—but do you believe Anderson can be implicated in any way?’ He had worshiped my brother for twenty years with a dog’s devotion,and—” “How has your niece conducted herself since her father’s death?” interrupted the detective. I stopped short and looked at him. A curious sinking sensation came over me. “Really,” I began; “you don’t—you can't suspect for a moment that—that—my niece could—could have—been in any way in- volved,” I concluded, desperately. His manner was extremely gentle as he replied: “My dear Mr. Smith, in all my career as a detective I have never suspected any one of a crime, I don’t allow myself to be mis- led by the bias which a suspicion would sah. I recollec The Cliarred Fragments of a Letter. generate. As far as individuals are con- cerned, my mind remains an absolute blank until I am sure that I have identified the criminal. Therefore, I begin by in- yestigating everything and every one.” Reassured somewhat, I tried to acquaint him, as well as I could, with my niece's peculiar disposition, going as far to explain the indifference she had certainly manifest- ed ever since her father’s death. As I have before stated, she had been gloomy and de- pressed—sulky, in fact—from the time of my brother's trouble with Ralph; and I was fain to confess that, since the terrible de- nouement, I had been utterly unable to detect the least change in her demeanor. Once or twice I had heard her talking to herself; but the only time I had ventured to console her was immediately after the discovery of the body, when I feared the shock of the first news might be serious. I was astonished at her calmness. She heard me to the end, and then replied: “I am not a child, uncle. I have borne other troubles, and I shall have to bear it. I will even try to “8 the best. Only one thing. I want to —that. I know Jack Ralph to be as in nt as—as I am; now let us not sp of it at all. It is too horrible.” = “You_may readily. believe,” I concluded, “that I made no er attempt at con- solation.”” = Phillips had istered without comment. “I hope you do rot think it worth while to examine my niede,” I ventured. ““No—no, I think not,” he replied, rousing himself from what seemed to be a fit of this—and 1 will belleve it may be | deep abstraction. “Not now, at any rate. I will have an opportunity of seeing her casually—at dinner, perhaps. The next step will be, I think, with your permission, to look at the and the clothes in which it was dressed when found.” I rose and led the way into the darkened bed room where the remains had been laid upon the couch and covered with a sheet. I-had known enough to insist that they should not be prepared for burial until the arrival of the city detective, though, of course, the physician and the local coroner had been obliged to take off the clothes, which they had thrown over a neighboring chair. Phillips at once proceeded to open the blinds. Then, with an even more serious manner than he had yet shown, he ap- proached the body and bent down over the white face. “The face has been washed, I presume?” he queried. “Do you know whether there Was much blood on it when found?” “There was some blood from the mouth,” I answered. “I would not permit them to do more than wipe it away with a hand- kerchiet.” “But do you know that no water was used before you came?" he pursued. “I am very cure of it,” I answered. “The netghbor who discovered my brother rushed at once to the house, where I was at break- fast at the time. Within five minutes of the discovery I was on the spot. The body lay on its back; and I noticed that two slender streams of blood had run from the corners of the mouth and formed a small congealed or rather caked pool beneath the neck. Phillips took a magnifying glass from his pocket and carefully examined the wound in the forehead. ‘A flash of intuition as to the line of his investigation came over me. “You think it possible—” I began. “I think nothing,” he said shortly, straightening up. “here is not a sign of blood having flowed from this wound. I can readily see traces of it about the mouth and neck. Nothing but a thoroazgh use of soap and water could remove them. Your brother did not die from the blow on the head. He was dead for at least half an hour before 1t was received.” A sensation of horror came over me at the words. I had been hoping against hope that Phillips might be able to show that the death was accidental, after all. Now I Saw at once the utter futility of entertain- ing such a notion. ““Moreover,"” he pursued, “if you say the blood was ‘caked,’ he must have beon dead for several hours before he was found. I took the trouble to examine the railroad cut on my way here. You will remember that its bottom is entirely shielded from the morning sun, the Jack of which, together with the heavy dews of the last two or three mornings would tend to keep blood more or less moist for some time.” i “What did kill him, then?’ I asked, at jast. “We shall see,” returned Phillips, and, drawing down the sheet, he proceeded to minutely examine the body, beginning at the head. Suddenly he stopped and straight- ened up‘again. I looked at him inquiringly, and-he pointed toward the left breast. “He must have had a pin or a needle in his undershirt,” I said, as I noticed a scratch less than gn inch in length a little above the heart. 8 “A rather long ‘fin 6r needle,” muttered Phillips, grimly, ‘and? Bending over, he pressed his thumfs\on each side of the hair-like line of b¥éwhing red scab, until it broke apart; and I‘'saw a deep, gaping wound, made undéubtedly by a very thin- bladed knife. It raf hgrizontally, across the body between the tbs, and seemed to range downward at an angle of about forty-five degrees, o For a moment tke fifterest In this dizcov- ery overwhelmed the horror of it. “But the clothes?"% sald, stepping to- ward the chair. ‘They. examined them.” Phillips’ lip curled. — “What's the gooWof examining anything,” he said, “when you start with a supposi- tion based on the firsi,bit-of evidence that appears. These .xokela never got beyond the idea that that Wouind In the head killed the man, so all their work was e and mseless. Now, “Ist''us see," ‘he pur- sued, and taking, yp the articles of apparel one by one he scrutinized each carefully— especially the shirt, undershirt and coat. “Where did the knife pierce these?” I broke in, as I peered over his shoulder. “I see no-—" “It didn’t pierce these at all,” said Phil- lips, putting the garments back on the chair. “Your brother did not wear these clothes when he was stabbed.” “But he wore these when he was found,” I said, vaguely, and with a consciousness of added mystery dawring slowly upon me. “You see the dirty stains where they lay ”” pursued Phillips, ignoring my remark, “that whoever killed your brother dressed him in these clothes and then carried him out_and threw him down that embankment. This is probably how the skull was broken.” “And that accounts for there being no blood on his linen,” I put in. “I don’t imagine there was any on the linen he did wear,” said he. “You forget that there was none on the skin in the neighborhood of the wound—just enough to form that tiny scab which you mistook for a scratch. I wasn’t sure about it; but I was looking for serious wounds and I found one. Perhaps you do not know that a deep stab with a very thin-bladed knife hardly ever bleeds externally, The internal hemorrhage was probably considerable, as the bleeding from the mouth would indi- cate, and@death must have been practically instantaneous.” I was all at sea now, and my mind whirled around amid a dozen haif-formed conjectures. Phillips picked up the shoes that lay near the chair. “He had these on?” he asked. I_nodded. “You can see, then, that the last time they were worn was in the house; that he could not have walked to the cut in them,” he pursued, unwinding an unsoiled thread of carpet from a projecting nail. This disclosure came upon me with crush- ing force. It seemed to point to some one {n the house as the criminal; yet to whom? It was impossible for me to believe that Anderson could be guilty, and yet who else was there? Only myself and my niece. At last, as I slowly gathered courage to ask some question in order to relieve my sus- pense, Phillips spoke again: “Perhaps it would be as well to examine your brother’s wardrobe with a view to as- certaining whether any garments are miss- ing. You see that the trousers on the chair here do not match his coat. If he were up and dressed, you'll doubtless find that the coat and waistcoat that do match them— if there were such—are gone.” Without trusting mys2lf to reply, I pro- ceeded to search carefully, but without avail. “You are right,” I sald at last. “They are missing—both of them; ard it was the suit he has been wearing eyery day. I cannot conceive my stupidity in neglecting to observe so notigeable a point, especially as my brother was 4 very careful man about his dress. te the shirt and un- dervest, I don’t know how many he had, but probably my njece+—” “Never mind those,” sald Phillips,shortly. “He had unquestionably dressed himself fully, and we shail bm safe in assuming that the murderershasi destroyed or other- wise disposed of mill ithe four garments through which the knife passed. Kindly permit me to examine the grate, although I don’t suppose—!* 11 He removed thdi chimney board as he spoke. The dust lay thick within, and up- on it the charredsfraaments of a letter. But for this the placeshad evidently been undisturbed since dt Was shut up in the spring. r id The detective leaned over and picked the burnt paper carefully up. It was perfectly black and fell to 2pieces in his hand. Of course no writing }wasi visible, much less legible. We both ,examined each minnte fragment thoroughly, with the ald of Phil- lps’ pocket lens, and it was apparent that both letter and envelope had been thrown where we found them within a very few days. Their freedom from soot and dust was enough to make that much clear to the most superficial observer. “Do you think it probable that this letter is in any way connected with the affair?” I asked. “I can’t tell yet,” he replied. “I shall be perfectly frank and open with you, Mr. Smith; and the case, as far as we have gotten, amounts to just this: Your brother was Killed in the house at some time in the morning before the usual rising hour of your family. Whoever did the deed either lived here, or broke in, or was let in by some one who lived here. It is evident, too, that robbery was not the motive, and the murderer appears to have been sin- gularly cool and deliberate in all his acts. I think we mf@y further astume that the murder was committed while it was yet dark. Otherwise it 1s inconcetvable that any one should ses Yisked carrying the body across the lawn.” A new idea, more horrible than any I had as yet harbored, came suddenly over me, and I grew sick at the mere thought. Was this man going to prove that my niece had let Ralph into the house to kill her father? The detective, however, seem- ed not to notice my agitation. “I presume,” he continued, “‘that no ex- amination was made of the doors or win- dows to see whether they have been tam- pered with?” I shook my head. Then I said: “Anderson reported to me that he found the front door unfastened, but we natural- ly explained that ty the supposition we “She shut the door in my face.” had already arrived. at—that my brother had walked out before breakfast.” : “And as we may feel sure that he did not walk out,” said Phillips, “we simply alter your supposition to assuming that the murderer opened it’ in order to carry his victim out. How the murderer got in, I shall be better able to tell when I have looked about a. bit.” He now went over the house very care- fully, with the exception of my own, my niece's and Anderson’s rooms; but though the lens was frequently brought into use there was no trace whatever of any house- breaking. “Don't you want to look everywhere?” I suggested. “It ts unnecessary,” he replied. “No would-be murderer would break into a hovse through the occupied room of a third party. It wovld only serve to double the chances of his detection. You may re- gard it as established that our man, if he entered at all, eatered by collusion with one of the inmates.” “Could he not have sneaked In on the preceding day and concealed himself?” I faltered. “He could have,” said Phillips, “provided he wanted to take big chat.ces; but he «id rot.’ ‘How do you know that?” I blurted out desperately. ‘Surely you cannot believe that any of us three let him in—” “I don’t,” said he. “But you said one of the imuates,” I persisted, now auxious to know the worst of his deductions. “J did,” he assented, “but was not your brother one of the inmates? I'm afraid you would not do for my prefession. What do you suppose Mr. Robert Smith got up and dressed himself for at such an hour? —some time before daylight, remember. I saw by a short glance through his medicine bottles thet he was not troubled with in- somnia—” “Never in his life," I broke in. “Well, then,” pursued Phillips, “it is quite clear that he got up quietly, dressed himself, admitted some one who came by appointment (probably asked for in that letter in the fireplace), and was killed by the man whom he admitted. That history seems to me to give a perfect explanation of everything, and no other chain of events begins to do so. If your niece, your ser- vant or yourself had admitted this person, or if he had broken in or been concealed in the house, surely your brother would not have been fully dressed before daylight to receive him.” “And if someone inside had killed him,” I added, “they could have locked the door again. “Yes!” said Phillips, grimly; ‘if they were fools, they might have pursued that method of fastening the crime upon them- selves. Your remark shows you just how stupid even the intelligent criminal can be and usually fs.” I felt myself flush at his words and tone; but it would have been worse than foolish to take offense. “Then it only remains,” I said, “to iden- tify the person who made the appointment to meet my brother.” “That is all,” he replied rather irritably; Phillips Started to His Feet. “put meanwhile, I imagine it is nearly your dinner hour, and, with your permission, I will go to my room and wash up a bit.” To tell the truth, I was not altogether sorry to be rid of my ally for a few mo- ments, until I could recover my compos- ure. I showed him to his room in silence. “We shali dine in about fifteen minutes,” I said, as he closed the door. Then I went to my niece’s room and knocked. At first there was no response, and I knocked again more decidedly. I heard her mov- ing, and a moment later the door was open- ed a few inches. Her face was set in grim lines. “I came to see whether you were not coming down to dinner. There is a gen- tleman here—” I began. “I should think you would know better than to invite anyone at such a time,” she said bitterly. “I certainly shail not come down.” “But, Mary,” I pleaded. “It is a detec- tive from the city, a Mr. Phillips, and the best man in his profession.” “So much the worse,” and she shut the door in my fac I went down stairs again, filled with new fears and anxieties. What would Phillips think of such actions? They could hardly fail to strike him as more than pecullar. Even in me they rearoused vague suspic- ions which I had practically laid aside. Still, if she’ was going to act so strangely, perhaps, after all, it was as well that he should not see her. In this state of mind I sat down to din- ner with my guest, pleading the excuse of a bad headache to account for my niece's absence. “Very natural,” he replied, as I went on to elaborate my apologies; “still, I hope to be able to see Miss Smith before my de- parture.” “I don’t know—" I began. “To tell the truth, Mr. Phillips, my niece is, as I be- lieve I intimated to you, in a very peculiar frame of mind. Perhaps we should be sur- prised by nothing, considering the shock she has received; but I feel that I ought to tell you that she resents your presence here and absolutely refuses to see you.” “Ah!” he replied, and then added, after a few secords of thought: “That is rather unfortunate, for it is absolutely necessary that I should talk with her, before coming to a definite conclusion,” “Are you as near success as that?” I exclaimed, fairly startled by the assurance of his enswer. “I do not know how near I am,” he an- swered testily, “but surely you can see how absurd it would be to go away without examining every inmate of the house.” “I don’t know how you can accomplish it. Mary is a very obstinate woman.” “Let me suggest,” he replied, more bland- ly, “that you frankly state the case to her. Say that I am an officer of the law and am compelled to do my duty, and that, if she will submit to the inevitable, my stay and the consequent annoyance to her will be cut short.” I acquiesced in the sound sense of this advice; and little more was said during our meal. When it was concluded, I went up stairs again to my niece’s room and Tepresented the situation as well as I was able. This time I found her, though in- dignant, yet more inclined to look at a reasonably. “Very well then,” she sald. “If I must see this—this man, I will do so; but be sure I shall have nothing to say to him, nor will 1 submit to being questioned. "When will you come down?” I asked. “Very shortly,” she replied, and again closed the door. I returned to the library, where I found Phillips and acquainted him with the suc- cess of my mission. "He bowed and made some remark expressive of regret at being obliged to trouble Miss Smith at such a time. Then we sat silent for a few min- utes. “I presume, of course, that you will ex- amine Mr. Ralph?’ I said at last. Before he could answer we heard the rustle of a woman’s gown in the hall, and Mary threw apen the door and stood in the threshold. Phillips started to his fect, with @ short, inarticulate exclamation. His face was very pale, and I saw him clutch the table as if for support. My niece eyed him curiously, with her head thrown forward and her lips tightly apart. Her look was at first vague and inquiring, as if trying to remember something, and then partook somewhat of the detective’s agitation. “T—I have nothing at all to say,” she be- gan; “‘and I won't say anything except that I know that the man you suspect is entirely innocent.” In a moment she had turned and disap- peared. I half rose to remonstrate and beg her to remain, but Phillips put out his hand and restrained me. “It is unnecessary,” he said: “I know annoe want to know.” resumed his seat, while I at him wonderingly and anpreuenatesle: He was now entirely composed, and no sign of his late agitation remained except an increase of his pallor and a deepening of the lines of his face. I recalled the par- graph in the superintendent's letter re- ferring to the bad health of his favorite de- tective, which had almost prevented our obtaining hts assistance; and I again re- proached myself for the thoughtlessness which had entirely ignored the condition of my companion. My reveries were broken in upon just as I was about to put them into words by Phillips rising slowly. “Will you pardon me,” he said, “if I ask you to let me retire? I am not entirely well, as you know, but I ¢ a full night's rest will enable me to do better work In the morning.” * I now took occasion to apologize for my lack of consideration, and to express the hope that he would sleep soundly, rise re- freshed and not allow me in my eager sel- fishness to drive him harder than the con- dition of his health would justify. All this I said as I led the way to his room, but he waived my protestations aside and insisted that he ‘would find himself entirely able to stand all that could be put upon him. After seeing that he had everything that he re- quired, I bade him good night. “I think I can promise you, Mr. Smith,” he said, with a peculiar graveness in his tone and manner, “ that we are very near the solution of this matter.’ Then he closed the door, and I went to my own room. Once there, I found time to look over the curious scene in the library between my Miece. and the detective, and the more I thought the more it disquieted me. His last remark, too, seemed to me, to say the least, ominous; and altogether, L slept little or none. I got up about half-past 7, and, after dressing hastily, went down stairs. Phil- Nps had not appeared, and I hesitated a while as to whether I should #waken him, deciding finally in the negative. Mary, of course, did not leave her room. At last the Glock struck ®. I went up to the detec- tive’s door and listened. Evidenily, he was not moving, so I knocked—genitly at first, then more decidedly; but without response. Finaily I ventured to try the door, only to find that it was locked on the inside. I now began to pound vigorously, listening, from time to time, until at last, thoroughly frightened by the -persistent silence, I put my shoulder against it and forced it open. Phillips. was lying on the bed, apparently in a very heavy slumber, although the daylight was streaming through the win- dow. His lips were parted and his cheeks seemed slightly flushed. I spoke to him and laid my hand on his shoulder. Then I recoiled with sudden horror. The man was dead—rigid—cold as stone, and had evidertly been dead for many hours. The shock of this discovery was so great that for a few moments I was utterly un- able to think connectedly. Little by little I began to realize the full extent of the calamity, and regret for what seemed to me the extinction of our best hope to learn the truth as to my brother's murder, was mingled with a deeper regret that the strain of my interests had been the last ‘straw to break down an overworked and useful life. Pervading all was the con- sciousness of a possibility too horrible to contemplate. There was nothing to do, however, but notify the authorities, and before the day had passed the house was again thronged with coroner, physicians, corstables and jurymen. The body of the dead detective was ex- amined. He had evidently prepared him- self for bed as usual; his clothes were laid carefully over a chair, and he had passed awsy in his slecp apparently without a struggle or png. breathed a sigh of heartfelt relief when the investigation dis- closed no evidence of violence, and the verdict was rendered accordingly: “Death by heart failure, occasioned by exhaustion and overworl My brother's funeral had been set for the following day, and I confess to some- thing of a mental struggle es to whether I should at once acquaint the local au- thorities with Phillips’ discoveries. Skid- ™ore, the village constable, was the last to leave me, and as he did so he took occa- sion to intimate that the solution of the murder had been pretty accurately arrived at, and that without the aid of “no high- falutin city detective.” “What do you mean?” I asked quickly. “Oh! nuthin’ much,” he replied. “Only we've found out that that there feller Ralph was seen a walkin’ up th’ road in aad Girection "bout five o'clock that morn- aay “Who saw him?* “Billy Gough. I reckon he don’t know much, but he knows enough not ter be fooled on a feller that’s bin ‘round here as Jong as Ralph has.” With this parting shot the local Hawk- shaw took his departure, leaving .me considerably perturbed at his information. I had begun somehow to feel satisfied of the innocence of the young collegian. A knife thrust was the last method a man lke him would adopt, and it seemed to me to bring the crime closer to the Italians with whom. my brother had quarreled. Whether this impression originated withi:: myself or whether I felt unconsciously ‘The Man Was Dead. that Phillirs’ conclusions were tending in that direction, I do not know. Still, I could not deny that this last bit of testi- mony was very material as circumstantial evidence. To be stre, Billy Gough was hardly half-witted, but, as the constable said, he knew Ralph well % ee not to be mistaken on a question of fils identity. I have forgotten to state that, immedi- ately upon my discovery of Phillips’ death, I had naturally telegraphed Superintend- ent Sanford, and that, by his directions, Inspector Ransom had come up to attend the inquest and to maxe arrangements for the removal of the body to New York. He had had litile or nothing to say during the proceedings,and Ihad left himinthe room occupied by Phillips, while I saw the con- stable to the door. As I turned back into the hall Mary was descending the stairs. Her face was agi- tated, and I surmised at once that she must have overheard Skidmore’s parting remarks,/a surmise which proved to be correct. “What did that man say to you?” she asked, coming close. i I told her in a few words, intimating, as I did so, a hardly felt doubt as to the re- Mability of Billy Gough's statements. “He was perfectly correct, neverthel he said, after a short hesitation. “I went out about 5 o’clock to meet Jack by ap- pointment, and to arrange to go away with him. I met him on the road, and he walked as far as the gate with me. It was almost 6 o'clock, and Jack went back to the yil- lage. He did not come even as far as the house, and I know he could not have killed father. As for your New York friend, who was trying to fix it on him——” “Mr. Smith, may I have a few words with you at once?” came a voice from the stairs. My niece started at the sound and darted into the library. “Certainly, inspector,” I answered. “Can I trouble you to come up here?” I mounted the stairs hastily, and Ran- scm drew me into the room, closing the door behind us. His face was more than Serious. : __Here is a sealed letter addressed to you,” he said. “It is Phillips’ handwrit- ing. I found it in the escretoire.” Utterly astonished at this new develop- ment, I took the envelope from him and mechanically opened it. oe me,” I said. Then I read as fol- 8: ar Sir: Realizing that my life must terminate vary shortly, I take occasion to cemmit to writing a brief summary of the discovered facts as to your brother murder. 2 “He was killed by aknife thrust inflicted frem behind. over the right shoulder, This happened in his own room, or, at least, in the house, and the murderer was a man admitted by appointment. The cl ee = the grate ig ger the com- nication asking for ti intmen: and must have advanced ag reksons 8 obtain one at such an hour. Let us sup- Pose that it came ostensibly from one of the railroad gang, and offered to disclose, for a consideration and under conditions in- sul secrecy, the directions given by some officer of the company to his subordinates to delay the work and to harass Mr. Smith as much as possible in retaliation for his persistent hostility. Your brother, feeling @s he did, would have been only too glag to get such information on any terms, he destroyed the letter, as was doubties stipulated for, rose, dressed, admitted his “What did that m: #Heged informant secretly, took him to his room, was stabbed, partly undressed and dressed again, carried out while it was yet dark and placed or thrown into the cut, care being taken thet his skull should be fractured as to apparently account for death. Then the murderer, having wrap- ped up the garments through which the knife passed, took them away with him. Much of this is in the nature of a itu- lation of facts you already know. It is the simplest thing in the world to see that the murder was not committed by your niece, your servant or by Mr. Ralph. The first could not have carried the body to the railroad cut, and neither of the others could have obtained an appointment at such an hour. Ralph, moreover, would never have used a knife, though I admit that, assum- ing the local theory of an early morning walk, a quarrel and a blow on the head, things would look very black for him. On the other hand, Anderson’ merely an ignorant man’ murdered his master and whom you and Miss Smith were shiclding. “Let me now go @ step further than we have gone together and add that it is per- tectly clear that Mr. Robert Smith was killed by an agent of the Mafia, in re- venge for the insults he offered that so- ciety. This theory not only supplies an ample motive, .but it also accords fully with the method of killing and the over- whelming evidence pointing to a delib- erately planned assassination, Moreover, every first-class detective must be familiar with the fundamental the Mafia make it certain that language such as your brother used would have in- fallibly marked him as a victim. The work was not done, however, by any man with whom Mr. Smith had ever been in com- munication, much less had trouble. The rule is that after death has been. decreed by the branch before which the case is tried, notice is sent to some branch Io-. cated at a distance, one of whose mem- bers—an entire stranger to the mattcr—is then selected by lot to act as executioner. Some member, then, of the Mafia was doubtless in the gang that heard your brother's tirade, made report of his words and the result followed. “Now let me inform you of a conclusive plece of evidence which one of those chances against which no criminal can guard has placed in my hands. Otherwise the task of detection would be- well nigh hopeless, but, as it happened, your niece and Mr. Ralph were walking along the road very carly in the morning and met the assassin coming from the direction of the house with the tell-tale bundle under his arm. Mr. Ralph would doubtless rec- ognize him again. Miss Smith has recog- nized him. Add to this the fact that the man is half Italian by birth and spent much of his early life among the peas- antry of Sicily, and I consider that I have sufficient evidence in hand to cause his ar- rest. tice almost equally well. As you know, I tried by every means in my power to avoid an assignment to this case, but, see- ing the finger of fate in my being com- pelled to undertake it, I determined. that my professioral standing at least demand- ed that I should pursue it exactly as I would any other, by the same means and to its logical conclusion. I do not think that I allowed myself to be influenced by any knowledge not coming to me as an- investigator, and the result shows that a clever offender can rarely be a match for an equally clever detective. Whatever else I may have been, my reputation as a conscientious and able official remains peLiouL eat. “Finally, I have, by the use of a table poison known only to a very few persons in Sicily, administered justice and avenged the law. Should you ask how a man of my intelligence, education and calling could lend himself to such an act, 1 will only say that I was a wild boy of fifteen when I joined the Mafia, and that disobedience to its commands meant cer- tain death. Then, too, you must nemember my Italian blood, and that we do not look at some things as do the northern races. “JOHN PHILLIPS.” There is little more to tell. When In- spector Ransom had read the above paper we both concluded that it ought not to be made public, unless necessary to clear an innocent man, and that contingency did not arise. My disclosure of the knife wound and the testimony bearing upon the time and place of the murder, together with my niece's relation of the causes and details of John Ralph’s movements, serv- ed to divert suspicion to some one of the Italian workmen, and there, with the aid of the police, all clues were lost. Ralph was discharged and, several years later, married my niece. I will only add that I have told you this story to hasten the flight of anxious hours and relying upon you as gentlemen to re- gard the facts related as strictly confiden- tial. Do you not think me justified in call- ing it “A Remarkable Case?” “Well, I must say I fail to see why feet are considered beautiful.”—Life.