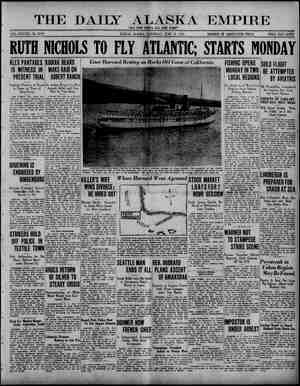

The Daily Worker Newspaper, June 13, 1931, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

eae ee DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, SATURDAY, JUNE 13, 1931 et their | lean ae kitchen. | tub on a| upboard. In ‘e a couple of dozen | y were very | hole inside of | unhealthily | not one crumb of! fo feed a cockroach. | stove, only | for the company refuses to sell to its | strikers even if they have money, ly had had nothing, They hoped to get | to eat at night, if the re- | ittee sent out to gather) wrrounding neighbor- | was all there was in that Up a narrow dark staircase, | e two rooms. One had an old in it with a bed tick so at when you lifted one end, whole hatfulls of stuffing came out | of holes that tore with each move- A pile of rags lay on it. “My leeps here,” said the man, point- to an eight-year-old boy. There was @ rope cornerwise across the | room, with worn overalls and shirt | hang: on it. There was nothing} else in the room. | | The last room had a bed, bigger | but as frail, and here there S one chair. Here too there was rope, on which hung an apron,| id some miners ‘clothes. A miners’ | cap hung on a nail. There was noth- | ing All the rooms were dark. All wert | small, about 12 by 14. | That's the way they live in Horn- ing. The company furnished the house, but the man himself had to buy the furniture. He even had to buy the stove, and the coal for the} now there was no fuel, which they don’t. This is a typical home of Horning. | and Horning is typical of hundreds of mining camps all around over this part of the state. Some are a little better; miners assured us some are much worse. Now this is why human beings live | this way. Before the present strike | 1. AMDUR. { nds, of workers, office em- nd. ool children, mane | presen| s from State, social | organizations at the railway | 1 to welcome the great Russian | | | n prolet: ‘Titer to the Red Capital. | Gorki intends te take up permanent yesidence in the USSR in order to enable him:to‘have a whole-hearted and active personal participation in the great’ Socialistic Construction. | The name of Gorki (in Russian this | word means “bitter”) is of course a household ‘word throughout the world. His writings..which are universally recognized to ‘be masterpieces of cre- ative, effort breathing the spirit of @ppressed millions who once groaned @nder the iron heel of the cursed fttocracy are Tread and known in every corner of the earth. Gorki is esscntially fitted to portray the mis- ery, ignorance,~superstition and des- titution that prevailed among the Russian peasantry of czarist days. He himself is 2 son of the people and sprung from. its. lowest and poorest stock. Bort in 2 poor working class family and raised in the familly of his grandfather ‘among numerous rel- atives, living inthe utmost squalor, | he was subjected to untold cruelties at the hands of his uncles and aunts. From his very infancy little Maxim tasted the bitterness of life. Later, Gotki, still at an age wien boys should be at school. struck out, fer himse'f. Fe shipped down the Volga as galley-boy, and then over a period of years was dock-laborer, baker, painter, watchman, boot-mak- er, railwayman, draftsman, lawyer's clerk, reporter on various provincial papers and finally he took up writing a8 @ profession, rs He went on foot from one end of the country.to the other and in many respects was.a tramp pure and simple but with this vast differnce that all | tions were later ‘y their simple, cre- | he observed,.the sufferings he saw, the terrible. miserable hand-to-hand existence in the struggle for life that ings were analyzed, dissected, weighed and stored away in his heart and he came. up against during his tramp- | mind. These experiences and obs@rva- | ative, sincere intensity to shake the whole world to a realization of the | indescriable hellish conditions and | slave-like existence of the Russian | toiling masses. At a very early age Gorki became associated with the young but grow- ing revolutionary movement in Rus- sia; first among the student move- ment and later with the workers. His creative efforts express that period of gigantic social changes vhen the capitalistic elements had verthrown the feudal landowning structure and when on the social arena appeared a new class—the Pro- letariat. While he was preparing for entrance to the Kaman University (this he never succeeded in doing) he organ- ized underground political circles among the student body of the uni- versity. In 1892 at Maikope, in South Russia, he was arrested for organ- izing a Cossack rising; and again in 1901 fell into the hands of the Ok- hrana (secret police) in St. Peters- burg (Leningrad), where he had es- tablished contact with the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, for writing a “criminal” and “treason- able” Manifesto to the Sormov work- ers. Continuing his political activities, Gorki was delegated in 1907 to the Fifth Congress of the R. 8. D. L. P. held in London. In the following years of reaction after the 1905 rev- olution, he settled on the Island of Capri (1908) where he founded 2 school for Russian worker propagand- ists. In 19%0, just after the publication of “Mother,” and “Enemies,” two epoch making books of the 1905 Revs olution, Lenin wrote of Gorki thus: Maxim Gorki is, without doubt, the greatest representative of Pro- letarian art, who has done much and will do still more for it, Gorki’s creative efforts undoubtedly signa!- izes the beginning of a Proletarian | to weigh 6,000 pounds now seemed to | trying to keep up with them, but | Marvin. You might come in again | couldn’t- cry out, she couldn’t argue, | Charities, thinking she might get Maxim Gorki Returns to | Workers’ Russia to Stay these men were working two or three | days a week, for what the company said was 45 cents a ton. But the was no checkweighman and old timers noticed that wagcns that used weigh only 3,900 or thereabouts. If! there was no coal to be taken out. the men had to stay underground 11 day in the cold, anyway. There was a lot of dead work (work that did not immediately and directly pro- | duce coal) and this they were never paid for. A very big pay day, the biggest of the several hundred pay | slips shown us by the miners of Horn- | ing, was $26.26. Average pays were $17.14, $13.23, $19.92, $17.88, $19.92, $17.88 and $18.92. This was the in- | come of the Negro miner who owned | the house we were in, from Nov. 30, 1930 to April 15, 1931, Each pay was for two week’s work. But he got no money. They took out $10 a month for the rent of the miserable shack he lived in. They charged him $1.50 a month for the company doctor, who never doctors the miners very much. By ZELL. ‘The neat little secretary at the Charity Organization Society picked | a card out of the file and looked it; “Yes, Mrs. Marvin, we'll do some- | thing for you just as soon as pos- | sible.” | “But the investigator came last} week—I thought maybe toda: Mrs. Marvin hesitated. 4 “We have been having so many| calls, all of us have worked overtime I'll make a special effort to have | your case put threugh right away. | Haven't you heard from your hus- | band yet?” “No, I haven't heard. IT thought maybe right now—you see, we hayen't anything.” “Til do all I can for you, Mrs. tomorrow.” The secretary examined her pol- ished nails, twirled a ring on her finger and went back to her type- writer. Mrs. Marvin turned away. It was as though someone had struck her @ blow that made her dumb. She she couldn’t speak. She had taken | her last nickel to come up on the subway to the main office of the some money, or at least an order for groceries. Now she must walk home—from Twenty-second St. clear down to Baxter. She didn’t mind that so much, though the icy pavements bit through the thin soles of her shoes. It was facing the children and telling them she didn’t have anything for them. A sharp wind had swept the usual veil of fog and smoke from the city and the towers of Manhattan stood } out hard and brittle against a biue | sky. Cars rushed by on the avenue in a steady stream. On top of 2 building farther down the street was | a large sign—a rosy-cheeked child} biting into a big slice of bread and jam. The red letters beside the pic- ture said, “Eat more bread.” A man on the corner was polishing apples and putting them in a row on top of the box. His hands were tough and blue with cold, and his nose red and shining as the apple he was polishing. He held it out to Mrs.| Marvin as she passed and said plain- tively, “Buy an apple.” By the time she reached Baxter St. her feet and hands were so numb it felt as though she didn’t have any. It was good to be in the shelter of the hallway, out of the sharp, stinging wind. She stopped a mo- ment to get her breath before slimb- ing the stairs. The radio in the little! cigar store on the ground floor was going loud enough to be heard all over the block.. “‘ . . . milk, the per- fect food. Each child should have a quart of milk a day. Drink more milk.” Slowly she climbed the three flights of stairs to her own floor. She had left the children with Mrs. Straub’ North Carolina Press, 1930, Reviewed by MYRA PAGE. [LLITERACY is,a problem which intimately conderns the working masses. It is they who must labor under its handicaps; it is they who are most determined that their children shall be freed from this blight, and attain more knowl than thetr elders had a chance to get. A real analysis of illiteracy in the United States, therefore, could be of much value to the revolutionary movement. However, this study of Mr. Winston's is of almost no worth, since it not only fails to give a basic analysis of the problem, but even fails to present any fresh, signifi- cant facts. The author obviously does not un- derstand the essential connection between the problem of illiteracy and the class rule of Wall Street. 'To him there is no relation, for exam- ple, between the ruling class policies of oppression of thirteen million Negroes, the colonial peoples and art in our country.” American Indians, and the fact that here we find the most appalling THE Hore of 4 Chicago RATLROAD WORKER) win denmonen. (NY is a? > Spite % YEAR \9385 Reson, 54 Drawn by a young Chicago worker, AXEL CARLSON, for a moment, dreading to ,go in How could she face them and tell them she had failed. But she couldn't stand there forever. She tapped on the door. Mrs. Straub, opening’ the door, saw the despair in Mrs. Marvin’s face and was quick to come to the rescue. “We thought it was about time for you to be getting back. I have some hot soup all ready. We were just waiting for you to come and eat with us.” Mrs. Straub added a dip- per of water and a pinch of salt to the already too thin soup and turned the gas a bit higher. Here, you sit by the radiator and get warmed up while I fix the table.” Mrs. Marvin took the proferred chair and rybbed her hands, whish were beginning to sting unbearably now that shé was in the warm room. Her three-year-old baby, Eva, came and climbed ‘up in her lap. How cool and saft her little hands around the red, swollen fingers. Joey, the boy, aged five, leaned against her chair. He looked up at her with dark, sol- emn eyes and said: “I’m hungry, mama.” “Yes, I know. Mrs. Straub is fix- ing dinner for us. We'll have it in a minute. Here, take my hat and put it on the bed.” Joey did as he was asked and came back to his mother’s chair. Mrs. Straub poured out seven bowls of steaming soup, for her own family of four and for the three Marvins. It was rather watery soup, but it was hot and fresh and for the moment it filled them up. Not until they had finished eating did Mrs. Straub ques- tion her. “Didn’t you get anything from the Charities?” . “No, they said maybe tomorrow.” Mrs. Marvin took Joey and Eva home and put them to bed. If she could just get them to sleep before they got hungry. again. “Didn't you get anything, Mama?” asked Joey as she tucked him in. “No, not today, Joey. Maybe to- morrow.” Mrs. Marvin went to the window and opened it for a moment. She leaned out, looking down thru the iron bars of the fire-escape to the who lived across the hall. She stood street below. Above the rumble and over rates of illiteracy. Child labor as a factor in illiteracy {s not even While in the population as a whole one in every 16 to 17 persons can not read or write, among the Ne- gBroes, one in five ig so handicapped and among the Indians, one in every three. In Porto Rico, Haiti and other colonies one-third to one-half are kept in this extreme of enforced ignorance. In the Black Belt, where the overwhelming majority of the population are exploited Negro peas- antry, every third person is iHiter- ate. Yet the author, ignoring such facts, concludes (page 79), that as the older generations die off, “even if no further efforts were meade to reduce the illiteracy and provided conditions remained the same, it may be assumed that the illiteracy rate for native whites of native par- entage would approach one per cent.” In other words, in the natural course of events, illiteracy will “practically” disappear. Only one million poor white farmers. and workers and three million Negroes and Indians will still be illiterate in ten years’ time! There is nothing clatter of traffic came the shrill voice of a newsboy. “Red Riot at Capitol. Police Club Hunger March- ers.” Mrs. Marvin wished she had been there instead of begging at the Charities. Better to die in the quick excitement of fighting than this slow agony of starvation. There was a knock at the door. | She hurried to it. Maybe the Char- | ities had realized her need and were sending her something tonight. But she was mistaken. It was only a boy trying to sell a Liberty Maga- zine. The knock had wakened Eva and | she began to whimper now for some- thing to eat. Mrs. Marvin brought jher a glass of water, but after a swallow she pushed it away. “There now, hush, darling, go to sleep and tomorrow we'll have some- thing to eat.” But Eva kept up her whining. Joey was still awake. He said, “Keep still, Eva. I'm hungry too. Mrs. Marvin went into the other room and closed the door. She walked back and forth across the floor, stuf- fing her fingers in her ears to shut out the sound of Eva’s crying. “My God! I can’t stand this. rl go crazy. I'm always telling them tomorrow—tomorrow. And I can’t go on living off the Straubs—him working only two days a week. They haven't enough for themselves. Why is it—I’m strong, able to work, will- ing to do anything—and yet I'm helpless. There is no work, but everywhere people trying to - sell something.” She stopped for a moment and took her hands from her ears. Eva was still crying. She clenched her fists and pounded them against her ears. ah ees For a long time there had been no sound from the next room. Sil- ence everywhere save the ticking of the big alarm clock on the shelf over the sink, and occasionally the faint rumble of the elevated a block away. The room was cold and Mrs. Marvin had sat huddled in her chair so long she could scarcely move at first. She had put a bathrobe on her dress for extra warmth— “ILLITERACY IN THE UNITED STATES” States is tenth on the list of na- tions having the highest rates of il- literacy in the world. What if more than 1,400,000 toilers’ children are always out of school laboring in the fields and factories. Ignore such facts as that in this richest country on the earth, there are thirty times as many illiterates (in proportion to the population) as in Germany and Denmark. Middle class native whites of native parentage, thank god, are well fed and college-bred. Some of them are even able to spend months of analysis on a problem and write @ book which is well received in the academic world—but which is a su- Perficial farce from beginning to end, This book: offers another glaring example of the utter bankruptcy of what passes in capitalist-run uni- versities as social science, Only Marxism and its dialectic method can furnish a genuine analysis of such problems as illiteracy; only a revolutionary workers’ and farmers’ government can remove this, along with other burdens from the shoul- ders of the toiling masses. Soviet Russia is demonstrating this. In 1913, under the rule of the czar, to worry about! What if the United Plenty a shabby, faded brown thing with frayed cuffs and holes in the el- bows. x5 There was a cord around the waist. She undid the cord and tested its strength, She pulled with all her might—it did not break. She turn- ed on the light and examined a gas pipe that’ran across the ceiling. She couldn’t reach it from a chair, so She pulled the table over and clim- bed on it. She took hold of the pipe and swung her full weight from it. It didn’t give way—it was strong enough— It must be Joey first. If he should waken she couldn’t go on. With Eva it didn’t matter so much. She wouldn’t understand. Mrs. Marvin tip-toed to the door and opened it carefully. The light shone thru the doorway and fell on the bed where Joey was asleep. Yes, he was sound asleep now, his breathing was slow and regular. What a tiny mound his body made under the covers. The hair curled thick and dark above his ear. There was a rather promi- nent vein on the side of his neck. Even in the dim light she could see it move as the blood pulsed through it. Joey, her first born... a smart boy... a handsome lad... everyone said so. But she must not look at him. She must remember hunger— she must remember fear... Eva cry- ing in the night... Joey’s eyes know- ing she had failed. She must do it quickly, before she lost her nerve. Carefully she slipped the cord of the bathrobe under his neck...how soft and warm his flesh...and tied it in a loose knot. Then she shut her eyes and gave the cord a quick, firm jerk. There was scrambling, a struggle, but there was no sound. With her eyes still shut she pulled on the cord with all her strength... for hours’ it seemed... until her muscles ‘gave way from exhaustion. She relaxed the cord slowly. There Was no movement...no sound. She undid the cord without opening her eyes. She dared not look at the thing she had done. Again Manhattan was roaring with life. Six million people surged thru the streets, were speded up from subways aud sucked into the sky- scrapers of New York. Six million people in a mad race for money, for fame, for pleasure, for success... a mad scramble... and some were trampled under... No sound came from the -Marvins’ apartment. The morning sun lit up a thousand buila- ings that thrust themselves defiantly into the air. It glittered on their tops of tile and polished metal. It penetrated a dinsy window on Bax- ter Street and touched a faded brown bathrobe hanging in the middle of the room. It touched the stiff, stick- like legs that dangled underneath. A piece of last night's newspaper had blown up and caught in the fire escape beside the window. It hung there now like a pennant—a head- line in forty point type—“Police Club Hunger Marchers.” ate. Today, in the face of tremen- dous difficulties, the Soviet Union has been able to reduce this illit- eracy by many tens of millions. In 1930 alone, ten and one-half million were taught to read, write, and cipher, and this year, twenty-five million more will receive this train- ing! By the end of 1931 four-fifths of the rural population will be lit- erate, and all but a small fraction of those in the city. By the end of the Five Year Plan there will be universal literacy. This is an achievement unequalled in the world’s history, and one made pos- sible by the leadership and direction given by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to the tremendous enthusiasm of Russia’s 150 millions of toiling population intent on build- ing socialism and furthering their own development, ‘The more than five million toilers in the United States condemned to illiteracy under the rule of Wall Street will learn this lesson, as well as others, from their Russian broth- ers. “Down with Illiteracy,” in order to be achieved, means “Away with three out of every four of het popu-| Capitalism,” and “Up with the lation on the average, were illitar-| Soviets” % SPREAD STRIKE AGAINST STARVA We could not find one man who hed anything but contempt for this doc- tor. The company charges him $2 @ month for light, whether he uses it or not. All the miners have to buy in the company store, the “Mutual Supply | Co.” On the front of a heavliy screened entrance, the manager of this store had a sign up: “The policy of this company is to handle standard known brands and to sell them to you at the lowest possible prices that quality and service will permit; also, | to have our employes serve you in every possible way and we feel that it is because of this policy that you favor us with your business and not because. some of you may be em- ployes of the coal company and feel that you should deal with us.” “Feel that you should deal with us,” is gentle irony. ‘The miner loses his job right away if he doesn’t. He gets brass money put out by the company to buy with at the company store. ‘We saw numerous store bills. Prices run: Flour, 4 cents a pound; canned milk, 13 cents; hamburger, 45 cents; lard, 20 cents a pound; bread, 10 cents a loaf—all the prices from 30 to 50 per cent higher than in non-company stores. ‘We asked a group of children lined up in front of the store: “Do you ever get any milk?” They hardly knew what it meant. No, they don’t get any milk. “What do you eat for breakfast?” “Bread and coffee,” they answered. “And eggs,” said one. None spoke of “What at dinner?” “Coffee and bread.” te a “Supper?” Supper is the hithers’ big meal, apts “Bread, soup, beans, meat,” they said. eal A similar quizzing of the adults brought out the same answers. . “There isn’t enough,” safa thany of the children. “We go withoutfood for days sometimes,” said the adults. ‘They looked it. foes “Most of the miners carry 4 Junch bucket of water to work, instead of food,” said others. Well, against such conditionssthere are 400 miners striking at Horning. Against such conditions thousands of miners march into the teetii ‘of’ dep- uties, state police, coal and {r6¥f po- lice. ‘They have shed the blood from their emaciated bodies already...They are putting up a noble fight:.They will win if they can get relief. | "Their local relief committees canvass the immediate neighborhoods. ‘Thei? dis- trict strike committee formbtljst its last meeting, Wednesday, a. district relief committee, with delegates from 11 sections of the strike. “Tuesday, June 16, thousands of jobless! and starving miners will march in/Wash- ington county, to demand seliéf for both from the government there: But all the strikers must have refiet. Send all possible funds, hold mass*’meet- ings, form united front cdiiiittees in the cities, collect funds and send them to the Striking Miners Dis- trict Relief Committee, 611 Penn Ave., Room 517, Pittsburgh, It is a > we sometimes cereal, or of fruit. strike against starvation! ‘ By WILLIAM GROPPER. Chairman of the Conference Com- mittee for the Launching of a Proletarian Culture Federation. ‘Tomorrow morning representatives of a large number of proletarian cul- tural organizations will meet in Ir- ving Plaza to found a federation that will embrace all the cultural groups in the New York area. The federa- tion will be formed on a broad base, to: include many sympathetic ele- ments. Through the federation it will be possible: 1) To co-ordinate the activities and to clarify the aims of all pro- letarian cultural groups of all na- tionalities, functioning in such di- verse cultural forms as ait, litera~ ture, drama, dancing, music, sports, cinema, education, nature-study, Es- peranto anti-religious work, etc. 2) To develop more effectively than in the past cultural programs for meetings, demonstrations, strikes and political campaigns. 3) To stimulate cultural activities within trade unions, fraternal organ- izations, workers’ clubs, etc. 4) To set in motion an exchange of experience and material among the various cultural groups, thus im- proving their effectiveness in the class struggle. 5) To-form closer contacts with the proletarian cultural movements in other countries, particularly the American colonies and Latin Amer- ica. 6) To reach broader masses of workers, especially Negro workers. “The federation will be loose, but it will not be a paper organization. It Proletarian Cultural Clubs”: ‘Confer to Form Federation leading force in every field of expres- sion, and in that way, win over the unradicalized workers as well as ths intellectuals—writers, artists. “scien- tists, students, teachers, -themists, engineers, etc. oy The motion picture ts a, posterful propaganda medium. The cost. of the silent film is comparatively cheap and within the means of mdity ors ganizations which could/ prods rev< olutionary working class films fed- eration can help to exhibit such films on a wide scale, ‘ The same applies to victtols rec- ords of workers’ songs, to proletarian literature whose publication, can bs made possible by subscription,.and to exhibitions of proletarian art which can be sent to all clubs ant“otgan- izations. tens This will at the same time stimu- late the individual writers,, artists, musicians, dramatists and others to create for the revolutionaty‘move- ment. sao Definite programs can be plgpned for national and internatiohal. con- tests and socialist competit can 'be arranged in every field of cultural ate tik dey Tt is impossible in the spa6e of 5 short article to discuss in detail all the advantages that will be, derived from the federation. The conference tomorrow is only a begirifiitigs the federation will undoubtedly within 2 short time expand into a'thational organization, embra¢ing the nearly 100,000 workers who are engdged in some form of cultural work car- tying its activity into the rattks of the hundreds of thousands.moré who will help develop to the highest stan- dard the prolstarian arts as weapons | of struggle. We must become the ing arms, the eyes like mine-pits Who'll stop them? ~ Strike! Down tools! They're marching, they're marching: Gilmore Buffalo Bertha Kinloch Avella. Coverdale Wildwood ‘Westland Renton STRIKE! What downpour of scabs can quench It’s spread the strike! Build the union! Clean out the scabs! Pars Better starve striking than working! It's Fight, Fight, Fight! TWO STRIKERS SHOT IN COAL MINE RIOTS Shoot, you bastards! When the flame {s leaping from mine to mine are in the grip of the churohes, ths YMOA’s, sport clubs, and other, geois cultural agencies, |They March in Pennsylvania By A. B. MAGIL, ey ees march in Pennsylvania! co aas 2,000, 5,500, 9,000, 15,000, 20,000 = Who'll stop them? i ie The miners are marching, the dark stony faces are marching, thesfwing- dug deep by hunger are marching. a pen ah GENERAL STRIKE SWEEPS PITTSBURGH MINE DISTRICT **“ They march, the years of hunger march, the bones of ing fists are marching in Pennsylvania! maim at wet Beit stowd on ra wav oso ‘ it? .