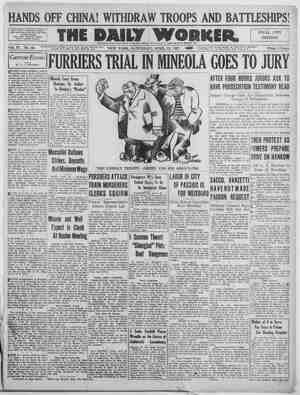

The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 23, 1927, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

The Story of the Five Coppecks Piece 6 By F. YERMILOFF. Potap Vanytch had in former times a grocer’s shop. He was church alder- man and being acquainted with the town thieves [jubka “Kasak” and Wasjka “Moment,” he bought from them stolen goods. The revolution struck Potap Vany- tch heavily, deprived him of his farmhouse with 55 dessatins and cut off his connection with the thieves. Potap became nothing, and a dread- ful hatred settled down in him firmly, enlighted his eyes with wicked fires and made a beast of him, deprived of its claws and tusks. Potap Vanytach had a torn nostril and his soul was torn too. Newspapers he can’t bear and reads only the holy Scriptures especially the Apocalypse. The latter he reads in drawling the words, looking with malicious eyes on the hearers: his old +sister-in-law, the old nun Eudokia and the calatch baker Eugraph Simonoff. After reading a page Potap Vanytch has for each Saturday an obligatory page, he lifts his eyes, closes the Apocalypse and says instructively: All happened just as it is pro- phesied here, MOle gc, The old women are sighing - and blinkin with their weeping eyes and the old. calatch baker, understanding nothing at all, nods approvingly — Just so—quite right... . Potap Vanyteh is fond of remem-: bering the past; he always begins his speech like this: In the old normal times .. . He calls “normal” times the years before the war, when he bought stolen goods from Kasak-Ljubka and Wasjka-Moment and helped to rob the peasantry. The Communists ahd the Soviet Power Potap Vanytch never calls otherwise than “those.” “Those” have supplied the coopera- tive with oil. Those are again on a meeting of the Soviet. i Not long ago Potap Vanytch casu- ally heard, that Chicherin visited the French states secretaries in Paris. Hearing it, he didn’t believe: It is impossible, that the French states secretaries have admitted “those.” The young communist Vassin showed him a newspaper. Potap Vanytch refused to read it, I don’t believe in those newspapers. But in the evening he said to the calatch baker Eugraph: Those have sent to France their emissaries to sell all Churches. . A dreadful but hopeless hatred was fondled by Potap Vanytch in his breast. ae * * The deceased son of Potap Vanytch was married to Tatjama, the daughter of the -moneyless Silaskyn. His widow lives at Potapoffs and works there like 4 mule. Often Pelagea Djatlowa, a member of the local Soviet, where she worked already the second year, told her: And why do you work for the torn nostril? Why do you feed his hatred with your blood? . Radio Factory Look back and see how your life is spent without use, But Tatjana was educated in pa- - tience and in heavy toil and without grumbling she carried on her yoke. * se * In September ofthe last year the nucleus and the young communists decided to organize IRA in the vil- lage. A speaker was called from Sysran. To the meeting came about two hundred persons, and it happened that Tatjana came too. @ The speech lasted over an hour. He explained the whole truth, touch- ing especially on the peasantry. After the speech a resolution was passed unanimously: It is necessary to render aid to our brethren! Pelagea Djatlowa took the secre- tary’s cap and went round: Sacrifice citizens. It is for our brethren! Five coppeck and _ ten coppeck pieces fell in the cap, all gave. Tat- jana took out her last five coppeck piece and put it into the cap. * * There can’t be any secrets in a village. Even if the cow of Stepanida gives instead of one pail of milk only a half—all women know of it. It thus happened also in this case: Potap Vanytch was informed im- mediately: Tatjana has also given a five coppeck piece. Why have you done it, asked Potap, and his torn nostril seemed to quiver. Because there are such horrors, be- cause the communists are murdered and hanged and emprisoned there. Those deserve it, answered Potap Vanytch, but I don’t understand what for my five coppecks had to be spent. They were spent for the com- munists, who are suffering in the prisons for the peasantry. ‘ These five coppecks! But yes, if everybody gives: fiye or ten coppecks that will make a sum of millions at the end. A green hue covered the fae of Potap Vanytch. My five coppecks for those! Ah, damned woman; ah... . * * * In the evening, when Tatjana was already gone to sleep on the hay loft, Potap Vanytch took a heavy stick and went upstairs to teach her “manners,” Are you here? Ay— Where are my five coppecks? Where are the five coppecks ? hoarsely cried Potap Vanytch. Thou helps “Those” , . . and lifting his arm to strike her with the stick, he stood aghast ... Something unexpected happened. - ++ Tatjana. got quickly up and barefooted ran away, soon disappear- in the dark, * * * The fifth month and Tatjana al- ready lives at Pelagea Djatlofts. Potap Vanytch remained alone. Of Pelagea he speaks not otherwise than: “Those put the devil into her head, and pointing to the Apocalypse he hisses out: . All this is prophesied there. H. C. SCHWARE. BLUFIFED my way into this job by telling the I boss that I was experienced in the line and I knew. more about radio than there was to know. 1 lied so straightforwardly, that. he apparently was satisfied that I was three years older than I usually say I am and he took me on, because I made a prac- tice but no profit wiring sets for some big corpor- ation. It is true that all previous experience with radio had been at a distancé, but when a man ts out of work and needs a job, making radios is also okay. The next morning I came in, went to the boss, and he gave me a slip to take to the fore- man. I got a pair of longnose pliers and a button, No. 443, which was my official designation in the fac- tory so that I must always wear it. I do not mind it, because when the foreman’s liver is temporarily out of gear he bawls out at that lazy, dirty, bastard, 443 who’s gonna get fired if he don’t stop talking. My work is simple. All day long I hunch my shoulders* over a long rude-logged wooden table, under a glaring light, covered with green tin and suspended not quite above the eyes of the workers. There are eight young lads at this table, all doing the same work, all the time. We all have longnose pliers in the ‘right hand, or a pair of snippers, and all we must do is squeeze. When the squeeze is on the snippers there is a- slight bite as the snipper bites the wire into two deliberate parts, Or if it’s a longnose plier, there is a Squeeze and a scroogy plush as the parafine is pushed away, show- ing a clean white line of wire. This is where ‘the conection in the set will be made according to the foreman. It is all hazy why the workers must do just this. I don’t know. The foreman told me to cut just these wires these lengths, and I cut them just so with never a deviation. I get a big tangle of wire-lengths. I pull them apart. There are a million different colors of those wires. The wax has melted in the hot room and is glistening under the fierce light as dew on a black-green leaf or like the oil on a new machine in the corner which is cutting plug-panels to length. I am just like that machine. I do not know why I snip these brilliant wires, I never know why, nor do I care to ask why. Only I know that I get eighteen dollars a week to do so, amd I do it just so. Just so. And all the time I must be careful not snip the wrong wire, ce There are eight boys at. the next table and at all the other tables there are girls. One day they ran out of wiring. The foreman was frantic. He grab- bed some wire sets from the girl’s tables and threw : them at us, The work was harder. Consequently the girls are paid less, receiving only sixteen dol- lars a week. From this hard handling of the steel tools, the hands are constantly full of abrasions. The net result of a day’s work is a coat of dank sweat; also a beautiful set of blisters. When I first came on, I wondered why they were wearing gloves. Now I know. The next best thing for blisters is to wrap court- plaster around the fingers, and over the palm and forget them. Nothing else can be done about them except to get a different job or curse the job. So IT put court-plaster on my hand which was numb with pain by this time, and continued gritting my teeth suddenly so as not to cry out when the steel bang-banged against, not only the palm, but the whole nervous system. The work is very wearying. No one ever stayed on this job very much longer than about a week or the whole set of workers would be insane. I didn’t like the job. I didn’t like the workers because I was too upset to even think coherently, On this job it is all a jumble of emotions. Even the girls. They quarrel fiercely. Or they brood over the longnose pliers. And over al is a great weariness, over all is a blue-and-white button with a number. Number 443. That’s me. I was not a person. I was a hand with a numbered button. It makes no difference if I am of a pleasant disposition. I can only brood over the longnose pliers. Brood and brood. And often a vision. Clear. And white. There is no coherence. Only a squeeze, squeeze, squeeze over wires whose destination or purpose I can’t realize. Only this eternal Squeezing and visions of the revolution. From the loins, from the shoulders of these lads in this factory and other factories. From the youth, when it is organized for fight. | VICE-PRESIDENT DAWES. © de “—_ Yule Store THE APPLE THIEF. POESY AND THE MACHINE AGE. In olden days the bourgeois miss Was worshipped by the bards like this: “Milady’s hair is twisted gold, Bright stars apiece her blue eyes hold. Milady’s voice tunes all the spheres, Milady’s music charms all ears. Milady’s like the daffodilly, Fair as the sun, pure as the lily.” But times have changed—the machine age’s here And newer forms of odes appear: “My sweetie’s like a flivver car; Her eyes more bright than dishpans are Her voice as pleasant as the squeal Of rivets driven into steel, My sweetie’s like a huge machine, Fair, pure, refined as gasolene,” By L D. TALMADGE.