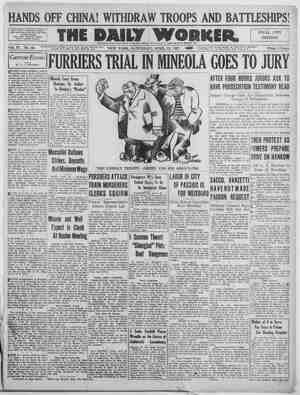

The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 23, 1927, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THe New MaGazZINE Section of The DAILY WORKER SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 1927. This Magazine Section Appears very Saturday in The DAILY WORKER. A Quarter to Spend IMMEY was walking slowly down one of the side streets. He wasn’t going anywhere in particular, merely sort of dragging his little legs in forward motion. And that he did listlessly, as tho he wasn’t con- scious of the fact that he was walking at all. Sud- denly he slackened his gait, and began thinking, kind of. It wasn’t regular thinking. “Oh, shucks,” he’d say awkwardly; “you know how it feels when a feller has troubles on his mind”; and Jimmey had lots of trouble on his young mind. Soon he ceased stépping entirely, his feet came to an abrupt halt, as a pair of dials cease to-move on a watch that stops going. He leaned against the window pane of a neighborhood book store, looking hungrily at the display of books. His right hand lifted the cap off his head, which he folded in two, and using it as a fan began shaking it in front of his face. . Jimmey was a slim, dark-skinned boy of fourteen. His lean face was pimpled and coated by a sickly pallor which was visible behind beads of perspiration that continually moistened his features. He wore a blue suit, The right ieg of his trousers was buckled over the knee, while the other hung loosely down covering a large hole in his stocking. His waist, un- buttoned at the neck held under its collar a loosely knitted ‘tie, the ends of which he kept twisting around his right index finger. “Whew, but it’s hot,” he ejaculated suddenly, allowing the back of his hand to glide across his moist brow. Jimmey had a quarter to spend. It was his first bit of real spending money in a long while; the fruit of a week’s toil. And, there were so many ways in which to spend it. Sc many things he longed for with a longing that only youth can feel. “Gee,” he lamented sorrowfully, as his fingers felt the piece of silver lying in his pocket. “If mom would only have made it a ‘half’ I’d a been able to get most everythin’.”. More than anything else, Jimmey had his heart set upon seeing a movie and vaudeville show combined. He hadn’t been to one in years; that he figured should cost at least twenty cents even if he sat in the gallery. Then he wanted to get some®candy, what good is looking at a’ show he argued if you ain’t got something to mtmch on? And a summer thirst urged him to get an ice cream soda. Jimmey heaved a deep sigh and continued toying with his silver coin, trying hard to decide upon which of the three desires to omit. Some minutes later he slumped away from the book store window and walked thru the moving columns of people. He seemed hardly conscious of the swarming masses that zigzagged.-wout him. His face gradually became animated by an overwhelming perplexity which évershadowed his temporary desire to indulge in sport. The corners of his mouth screw- “ed up into two dejected lines, which soon lost their indentity in the pale hallow of his cheeks. Words began to form into sentences and rotate around in his head. Sentences which lost their meaning to him. He was utterly confused by the many problems which weighed on his mind. Only one word broke thru his silent soliloquies which he distinguished from the rest, and that one syllable SCAB beat a steady tattoo against his hopelessly baffled senses. He did not understand its mean- ing, yet the letters of the word S-C-A-B separated and each letter danced teasingly before his eyes. He continued sauntering along, until he passed a gaily decorated theatre. There he paused to gaze at the colored posters, forgetting temporarily his unhappiness, : 1. Jimmey worked in a sweater factory. Yester- day he received his first pay. It was a small yel- low envelope with his full name scrawled in the center, and its contents eleven dollars and sixty cents marked in a corner. It was handed to him by a cashier as he walked out of the factory at noon. He pocketed it with the suppressed joy of a student receiving a diploma on graduation day and hurried out of the building. His limpid blue eyes were ablaze with a keen delight, which was intermingled with an apparent uneasiness. : It was Jimmey’s first week at work and he felt vaguely elated. He found the job after a despairing search. He liked his work too; it was a bit hard at first, but he was willing to’ work hard; beside he was promised promotion soon, and,’the pay twenty- five cents an hour was more than he hoped to re- eeive for a start. } ' “Now, ‘mom’ can take things easy with me work- in’,” he kept repeating. He would see to that. Jim- mey hated to see those women from the settlement house bring them weekly food. The were thought that with his earnings they could once more assume independent means, was sufficient to elevate his spirits. He visualized many improvements his wages would bring about in the house. In a few weeks he hoped to be able to buy his mother an electric iron. She always dreamt of haying one. That meant a great deal to Jimmey, end he felt the pressure of his responsibility keenly. His joy at finding employment was short-lived. For three days later the factory workers walked out on a strike for better conditions, while Jimmey together with several others remained. He couldn’t understand why he should relinquish his joh when he was so anxious to work. The strike he was told by the boss, was called by Communists, and he made up hig mind to have ‘nothing to do with it. Jimmey continued working that week, but with an entirely different feeling. Everything seemed to change. His lips no longer whistled as they did the first two days. He felt sullen and morose withont knowing just why. Each morning when he came to work, groups of girl strikers picketing the factory would circle about him and ask him not to go up. When he would refuse their request by shaking hig head, they would jeer at him by calling “creature” and “scab” as he entered the building. Then a police- man, posted nearby would chase the strikers away, sometimes hitting them with his club. It was then that anger gushed to Jimmey’s face. He would begin to hate the girls, but he wasn’t sure, per- haps it was himself he hated more. The red-faced policeman he also disliked. He wondered why he was there, and why all this strike trouble had to happen. Jimmey resented greatly being called “seab.” A. precocious intuition, born’ out of the working class atmosphere he lived in, informed him that he was doing something wrong by working — something dreadful; but just what it was he couldn’t fathom. He was afraid to tell his mother that there was a strike in the shop, fearful lest she tell him to stop. And yet the desire to bring home a pay envelope such as the one he had just received was so great that he gritted his teeth and determined in his own childish way to stick it out, come what may, tho inwardly he was very much agitated and ashamed of himself. He hurried home in long jerky strides, his heart palpitating rapidly. His hand kept reaching to his pocket, feeling eagerly whether the previous en- velope was still in its proper place. The figures, eleven dollars and sixty cents loomed in contorted shapes before his eyes. It was a munificent sum to him, more than he had ever earned before. Reaching the drab apartment house where he lived, Jimmey ran up a flight of dark stairs, and pushing open a door entered the kitchen, which was a narrow and illy-lit room. Its only window faced a mud spattered wall, belonging to a neighboring tenement. A narrow yard, separated the two houses, where sunshine seldom penetrated. When it did, it was as throwing the rays of a powerful search- light into a deep chasm. A dim: flame flickered from a half open gas jet, throwing a faint shadow of light over the room which was filled on this day with a stifling humidity. His widowed mother stood over a gas range dropping sliced bits of potatoes into a cooking pot. Jimmey stepped softly to her and withdrew from a pocket the coveted envelope which he handed to her with an affected smile flickering across his lips. His mother wiped her wet hands in the folds of her checkered apron and looked at him, quietly receiving the extended offering. Their glances met in a silent look. She counted the bills and extracted a quarter from the change which she handed to Jimmey, who muttered “Thanks, ma,” and promised not to spend it until Sunday. After supper he donned his other suit and hur- ried down the street. He shrunk away from his friends who called him to join their play, feeling no inclination to do so. He felt above mere child play. Jimmey considered himself a worker now, a real one, he argued; punching a time card four times a day and everything, same as the others. He kept repeating “worker” over and over again as one learning a new. language. - It fascinated him. If only they wouldn’t call him scab when he came to work, he could still feel happy. He sighed longingly. ALEX BITTELMAN, Editor By ALEX JACKINSON Events of the past week kept spinning about in his thoughts. The deafening noise of the heavy weaving machine to which he had not yet become fully accustomed drummed noisily in his ears. Each tick-tock held a distinct message for him which he was readily learning. The ever changing panorama of scenes ecntinued to spin faster and faster. He couldn’t escape from their steady hammering—not even in thought. The maelstrom into which he was suddenly swept had no exit, The massive machines assumed in his reflections grotesque proportions: They were overated by ugly looking foreigners, hired especially as strike-breakers. Jimmey hated them. They all looked so stupid to him. He won- dered why THEY didn’t strike like the rest. Did they all have mothers to support like he did? Jimmey eyed them curiously. The way they ran after the rapidly-moving spindles interested him. Soon he would become a weaver himself and run his fingers over the silky threads as they did. He thought that he would rather like being a weaver. Then he pictured the girls picketing in front of the building. If only they would leave him alone, things would still be alright. “What business is it of theirs. aryhow if I work or not?” he mused. il. Jimmey, continued gazing at the brightly deco- rated advertisements of his favorite actors until he became conscious again of his unsettled prob- lem. He recollected his thoughts and once more proceeded on his way. It was an exceedingly hot summer day. And an intense heat filled the streets with a pungent hn- midity, which the sweating populace both in and out of doors seemed to absorb, as a sponge absorbs water. The unwashed streets were everywhere lit- tered with fragments of dirt. Here a grocery keeper just dumped a barrel of decayed vegetables into the gutter, which in unison with the open re- fuse cans around the tenements yielded forth an odor. The stench of decomposed garbage filled the atmosphere. To the masses this was a familiar scent, which they inhaled as on other streets people inhale the fragrance of a perfume, Yet people moved. Everywhere the hot pave- ment was crowded with shuffling feet. Their cloth- ing moist from perspiration, clung tightly to their warm bodies. Yet they moved. Body after body ~ appeared and disappeared, in a never ending pro- cession up and down the street, The vista of bobbing faces swept by Jimmey like the babble of a language one cannot understand. He paid no attention to the many bodies of women, Some misshapen by toil, and others hollow eyed from fatigue which continuously circled in and out of his gaze. Men, their heads topped by white straw hats, joined them in the grim procession. They were mostly garment workers, pounding the pave- ments with their staccato steps on their one holiday in the week, Jimmey looked about him. On the corner he saw a red-faced traffic cop lift the cap off his head and withdrawing a handkerchief, wipe beads of per- spiration from his brow. At a soda fountain stood a fat man drinking orangeade, part of which trickled down his shirt. His attire evoked a grin from Jim- mey. Here a woman screamed, as a taxi almost ran a child down. There a mother was nursing her baby on a stoop. Elsewhere a storekeeper lowered an awning hoping it would offer relief from the heat. Here another woman in the shape of a barrel pushed along a baby carriage. Down the street a fireman rigged up a temporary shower, under which children romped. This was the east side. There where people do not make ethics of their be- havior—and where the drums beat loudest. The drums of revolution that beat everywhere. What a tableau! A circus for Maximus! From out of the shuffling crowd stepped a young woman. Jimmey looked at her wondering where he had seen her before. Suddenly he recalled her; she was one of the girl strikers who had called him seab, She too had recognized him, and was just about to ery “scab” when she restrained her- self. There was something pathetic about his per- son, something of hopelessness which she could not help but notice. She cast a furtive glance at him and prepared to move away when Jimmey’s arm reached out and touched her gently. “I know what you're thinkin’—and I’m sorry— honest to Christ I am,” pleaded Jimmey—“an’ I won't do it no more. You'll see-—You’ll see” he con- tinued passionately, almost choking with emotion, (Continued on page 4)