The Daily Worker Newspaper, November 6, 1926, Page 16

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

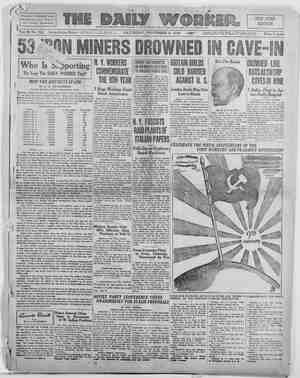

Women in Soviet Russia _ - By L. S. Sosnowski. was Nekrasov, in his excellent poem ~—- “Russian Women” — who sang about two princesses whose, eatire virtue consisted in the fact that they followed their husbands in exile to Siberia. And how many generations of youth grew enthusiastic out of pure emotion and perhaps with tears for this story of the deeds of the two Russian women. But no one directed at Nekrasoy the reproachful question: And were all women of that time and of that circle like these? I want to tell about Russian women of another time and of another sphere. My heroines do not even know that they are heroines. Let us begin with the name of my heroine: She is not a princess, no Wolkonskaja. A peasant woman of the government of Rjasan—Anna Agap- kina. You understand: no Agapova, but simply an’ Agapkina, The sur- hame itself reveals her low origin. For the serfs of the prince (even if it was the enlightened and humane prince and Decembrist, Wolkonski) were not called Agap, but simply Agapka. And the children were just Agapka’s children, eMéhat then is the achievement of pe Agapkina and what has given her the right to public attention? She is the editor of a Magazine, “The Re- surrected Wanderer.” Dear reader, have you hever seen a copy of this magazine? Perhaps you have not even heard of it? That would be unfortunate, This mag- azine pursues a far-reaching program and is profusely illustrated. Where is it published? whom? It is published in the village of Sseitovo, government Rjasan (post of- fice of the village Boluschevy Pots- chinski) “by a village literary circle” —so an article by the editor tells us. The actual editor, however, ig Anna Agapkina, peasant Woman of the vil- lage of Sseitovo, She writes: ee I often think it is the cry of the longing soul, the blade of straw of the remote and gloomy village sinking into the darkness. The people are yearning to come out of the dark- e-ink ae ae! In Sseitovo there are no print- shops and no typewriters, Semi-illit- erate peasants, men and women (Vil- lage Literary Circle), hand in their creations to the editor and the latter writes them into the notebook during sleepless nights. And when the mag- azine is ready, it is Sent out, then it wanders .from Village to village. Hence it_is also called “The Resur- rected Wandered.” On the cover one sees @ more than naive, child-like drawing: a girl accompanies a lad. Then follows a poem: And by “Dear friend, escart of sleepless nights. . , Grey wolves you will meet more often on the road, We shall not hear your cry for help. But do not grieve over your grue- some fate; In the summer, when the work is done, Then you arise to new Ilfe again. Then a new “wanderer” will travel the old noads.” How the journal arose, we learn from the article “The Resurrection” (also by the same Agapkina), “Like stammering children, At the _’ beginning we had much that was quite. disconnected and eva vs content, In Spite of. that however, we felt our- selves happy when we gathered to- gether and read our writings to one another They appeared marvelous to us, better than anything in the world. “On this evening we experienced a restrection; Some thing inconcciy- able, new,. bright arose in us. Only few among us could find their way in the sphere of literature. Interest burned in all faces and the hearts be- heath the thick husks strived to grasp this hitherto foreign activity. Our corversations and criticisms often ex- tend far into the night.” The editors of the journal treat contributiors in their own manner: essay ion the great significance of lit- speaks of searching into the sphere of her native home and its cultural history. everybody of the necessity of collect- as well as non-literary. old marriage custom, The bride weeps and wails: youth, whither are yon going? How shall I live among strange people, able to grip her, Just read the journal] three-fourths of which is filled by her. Here an than from the understanding. She writes the following concerning the reading rooms and says very well: “The mill, the reception room of the doctor, the waiting room of the land- erature, poetry and art. There she transformed into reading rooms, Life itself creates‘ natural reading halls here. Everything else only calls forth restlessness and boredom.” People’s health—who knows any- thing about it in a Russian village? Our editor deyotes a special article in her journal to the question of hy giene, to the necessity of learning the life 6f one’s body. Anna Agapkina convinces ing monuments of antiquity, literary “Let us take for example the very ‘You, my free life, my ing place—all these places must be ~ how shall I serve them. , .’ These words contain a deep meaning: In them lies hidden the weak revolt against the fearful slavery of the Rus- sian woman. And when we martyrs of the former slavery, will have died, then will such a museum tell poster- ity how we lived and suffered. Fu- ture generations will know how the rejoice and are over-happy that they | mother-inlaw tortured us, how the too are writers. They often bring us | drunken husband gruesomely beat us. oddly looking shreds of paper: on one}. In a word, a lot can be written little piece of paper one recognizes | down concerning the old life.” with difficulty a little house or some- The fate of woman occupies her thing like: it. Embarrassed, with se- Here are her thoughts cret proeedure,: expresséd in a= poem: drawings. We have decided that in| “You slave, most unhappy of ail such cases it is not necessary to re- slaves, flect very long—everything ig pasted | For the first time you have heard together, bound and given as a prem- the call. 2. iuma with our journal. We did not| You have become free, sister! krow how to act otherwise, and we; Who could feel your hopeless fate, “We lack the heart to tell onyone that his work is no good. One must be a hard, blind being not to see the shyness and excitement with which the author reads his work. And if one says to him: ‘That’s fine, keep on writing; we will copy it all and include it in the magazine,’then many our work with benevolence. It is not] You could feel your hopeless fate, easy to be active in the village in this} Your hard woman's fate?” manner, One has to be satisfied with Also in her prose, Anna Agapkina little. ‘S with the peasant woman in It is so dark in the village }s ” an especially tender and cordial man- Former waiters and porters are bad farmers. Anna Agapkina writes an article on farming. She had taken farming courses. And she must show that “the cultivation of vegetables is very lucrative and the vegetables very nutritious. But only few of us possess these easily accesible things in sufficient quantity.” Painfully she cries out: Inability to live and to understand the meaning of life is manifested everywhere. “We must not be shocked by the darkness that dominates us; we must exert ourselves in oner te Mluminate | ee” 4 i Anna Agapkina Belt nls the” pro tection of forests, the necessity of forest economy, the laying out of gar- dens, the erecting of brick-kilns: “We need not suffer want any more, and go begging, tears in our eyes, for bricks for the oven, or a crumbling chimney.” That is the resolution of the com- munity meeting in a village which had decided to build a brick kiln after a lecture by Comrade Agapkina, We shall talk later of the magazine. Anna Agapkina is not satisfied with merely editing the Wanderer.” Besides that ahe also POS Rin a reading Toom and indeed ‘according to her own plan: “One day in the week the reading room is given over to the younger school children; an- other—to the older and half-grown children; a third—to the youth. The : days—to the adults. Then the therefore beg you comrades, to judge late sufferings, meeeredipn issuing of books and collective read- ing also takes place.” Since all state publishing houses are very far away and cannot be reached, Anna Agapkina wrote her own revolutionary fairy tales for the small children. Since 1920 she has ventured to publish a children’s jour- nal together with the children. But we must not forget that in ad- difion, also her farm work, her fam- ily cares weigh upon her. And the difficulties of village life! Around her it is dark. Half of the village con- sists of former metropolitan waiters whom the revolution had driven to the village. The other half consists of former porters and similar peo- ple. Embittered, long unaccustomed to the heavy farm work, longing for tea tray and napkin, miserable, de- graded, but nevertheless wishing for the lost restaurant paradise—these people have little sense for literary endeavors, In this heavy atmosphere, Comrade Agapkina performs her cultural deed. She has been a member of the party since 1917. For some years she breathed the Petersburg air. In the beginning in a leather factory, then as a street-car conductor, the famine of 1918 drives her back to the village. Purely, political work does not inter- est her, Only the cultural OS PEE RRR AES cure 8g ig ee "1 10 ner. With warm participation, she Thus in a dark gloomy village, in a ives her advice as to what is to be struggle against century old ignor one when the family life is broken}ance and the idiocy of village life, up—she calls her to public service, All this comes rather from the heart there works a sensitive soul, a lyrical poetess, a young Communist peasant. THE TINY WORKER Special Russian Rdition. Honorary Editors, The Young Pioneers of Russia, Johnny Red, Assistant, A Weekly, Vol. 1. Saturday, November 6, 1926 HEY CHICAGO! In Chicago, to- night, the Van- guard Group of the Young Pioneers are celebrating. Holy Cats—what aswell affair! It’s called the ens =~ and everything is pre- by the Pilo- neers: the fun, the food, the Panel ‘n’ overt ng. — fun starts at Pp. m. and the place 4s 2733 Hirsch a ldye ever see the new dance call- ed the Pg Re ble?” and little Reds will be doing it! Be sure to come oyer tonight. BXTNA Te next issue of the TINY WORKER is. a special GRAND A POSTER FROM RUSSIA. RAPIDS issue, Isn't it a dandy? ‘The line on top oF Thee Pioneers of reads: “On your ninth this town sent “Woman Become Literate!’ birthday we make Johnny Red a The lines at the bottom read; the Young Pio- bunch of news, “Oh, Mamal If you were literate | neers of Russia poems, stories, | you'd be able to help mel? honorary editors of and everything. Oh, Boy— wait ull you see it! this issue. We wil send o jes of this eave of This is the way the Tiny Reds in Russia learn how. to read and write and they help their mothers to learn. a A workers’ government wants every- | the TINY WORK. HEY WHAT body educated. Isn't this poster a | BR to all gro: CITY WILL of Russian Chile beauty? Clip it out and paste it in one of your school books! . BR NEXT? snappy tal tl soecnatitee “FARE RP VaR edt techn cineca thetansit ec easinpattittaailateststihatti