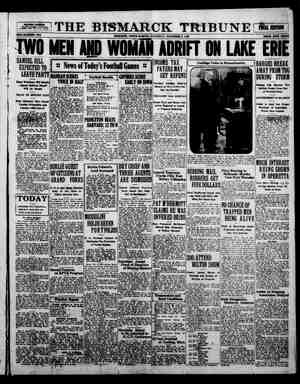

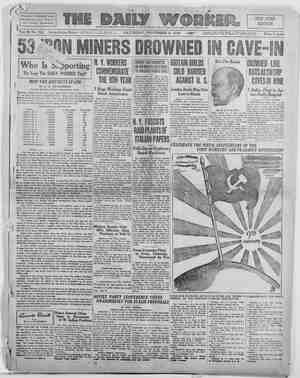

The Daily Worker Newspaper, November 6, 1926, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

’ Russian literature. Renee eannmaemmen Alexander Blok, the Poet of Destruction and Creation By SCHACHINO EPSTEIN. creative activity of Alexander Blok enters a new phase in the pooms “The “Twelve” and “Scythfans.” This sudden bouleversement meets a response ranging from surprise to mystifion- ton. “How did it happen,” asks the “populist,” Ivanov Ragunnik, “that Block, the decadent, the high priest of individualism, the propliet of art for art’s sake, for whom pootry is a matter of form and not of content, how did Block come to descend from ‘his heavenly Darnassus to this simply, bloody earth of ours?” For Ivanov Ras- umnik this is a riddle. He sees in it the great miracle of the November revolution, when the ideas of the “populists” spread. like wildfire and even. took possession of so extreme an individ- walist as Alexander Blok who had always mis- trusted the collective will of the people and ex- alted ¢he personal will of the individual. Ivanof Rasumnik claims Blok as an adherent of the Left Social Revolutionists, who, saw in the October revolution the fulfillment of that special mission of the Russian people, which Herzen and the revolutionary “Slavophiles” had predicted. Other Russian critics offer a similar interpreta- tion of the new manner of Blok, tho their ex- planation of bis point of view is somewhat dif- ferent. For most of them, “The’ Twelve” and “Scythians” mark a turning point not only in the creative work of Blok, but in the whole of A correct view is taken by the Marxian, Lvov- Rogatshevsky, who pointed out the new horizons which the November revolu- tion opened to Russian poetry, which now tends to become the expressions of the people, the col- lective creation of the masses, and not of the individual intellectual, the offspring of the well- educated aristocracy. But the change in Blok’s own creative activity, Lvov-Rogatshevsky, offers no more satisfactory explanation than Ivanov Rasimnik. Neither of them has penetrated to the source of Blok’s earlier work. They have failed to find the routes thru which Blok’s impul- sive spirit was nourished during the entire per- of his creative activity. There is in the development.of Alexander Blok a great similarity to thatuof the Belgian, Emile Verhaeren, who had also passed thru the evolution from individual- ism to collectivism, from the expressiom of per- onal experience to that of the masses. The two poets differ, in fact, only in their atmosphere, their national surroundings. Verhaeren was a typical son of Flanders, where the remnants of feudalism intermingled with the rising capital- ism. It was to the comingling of these two cultures that Basalget, the. best biographer of Verhaersen attributed the “poetical chaos” of the first period of Verhaeren’s creative activity, a chaos which gradually disappeared as the feudal culture was absorbed by capitalism. Verhaersen, the Fleming, became a true son of Brussels. He departed from nature, which he had sung so beautifully, and which had expressed so well his individual mood, and he came to the great city with its tall factory chimneys and its eternal roar. There he mingled with the crowds in the noise of machinery and th& pulsation of locomotives, he heard the music of the future. And this music was interwoven with the tones of the decaying villages of Flanders, their sorrow and despair. Thus Verhaeren’s creative work became the ex- pression of two conflicting cultures. The deeper the despair of the vanishing culture, the more gay and jubilant the notes of the strong young cayilization which was replacing it. The city had conquered the village and out of the victorious — city rose the “Dawn” of Verhaeren. This natural evolution of Verhaeren as the true son of Bel- gium and time, explains the divergence between the creative activity of. Verhaeren’s first period, and his last, between his individualism and col- lectivism. ‘The latter evolves naturally from the former, because such was the evolution of the whole Belgium culture. LEXANDER BLOK is the son of St. Peters- burg, where “East” meets “West” and Asia becomes Europe. These two cultures Blok im- bibed with his mother’s milk, and he became the greatest follower of Dostoievsky, for whom St. Petersburg was the symbol of Russia. The first period of Blok’s creative work was the expression of the spirit of St, Petersburg, with its overre- fined and biase inielicentaia, the last word of Wuropean culture. At this period he was the real Russian individualist, }coking down upon the peo- ple, longing for the advent of the Nietzschean super-man, while he drowned his inner pain in no less real Russian orgies, which revealed the Asiatic aspects of the soul of the Russian peo- ple. Blok’s “Beautiful Lady,” his earlier sym- bol of Russia Buropeanized, slowly merges into \ s\n the “Oriental Mary,” the sinful, wanton, Mary, who becomes the mother ef a new God. This Mary he finds not in the aristocratic salon, the gathering places of Russian society, but rather in the lowest depths, among the course and ig- norant, as yet untouched by HBuropean culture. There in the musty cellars where “Vodka” and the “Hormoshka,” (accordion) kindled the soul, Blok provides some new force, incomprehensible, wild, brutal, but at the same time holy, as Mir- fam, who sells her body and gives the world a Christ. Blok thus belongs at this period to two worlds —to Europe and to Asia. He tries to unite them to give the first the barbarity and vigor of the second, and to the second refinement and ele- gance of the first. The result is poetic chaos, as dm the case of Verhaeren. He is not quite conscious of his own impulses, but he feels that somehow St. Petersburg must become the metro- polis of the world, the barrier between Europe and Asia must be effaced, a new world culture created under the name of Petrograd. The first Russian revolution broke out. For a moment Blok thinks that his dream had come true. He forgets his “Beautiful Lady” of yore. Mary is now the idol of his heart. To her he kneels, and the calls upon others to follow his example. ‘Do you not hear the new music which —Emil Verhaern fills the universe?” he says. “It is not the music of your piano, nor the gentle notes of the violin. No, it is the music of the trumpets of a wild army, full of-hate, which destroys everything it encounters. This music is the echo of a ter- rible storm which shatters heaven and earth, and woe betide you, if you close your ears. You will sing again into the shameful prostitution of house pianos and violins, and you will not notice that beneath the stormy clouds the soul of a whole people is purged to purity and holiness, to divin- ity itself!” B's call was as of one crying in the wilder- ness. Stolypin strangled the first Russian revolution with his famous “necktie,” and Blok’s comrades worship at the shrine of Artzibashev’s Sanin, Zologub’s “Petty Demon.” Blok pauses as if in confusion. He does not return to his “Beautiful Lady,” and Mary has not yet ap- peared. He pours out his heart in poems of dis- appointment and despair. He feels that there is no way back.to the old, but the new is still covered with a heavy veil. He tries to lift the veil, to penetrate into the future. He speaks the bitter truth to the Russian “intelligentzia.” He reveals the deep abyss which lies between the in- tellectuals and the people, in words that ring like the scourgings of a prophet. And when the world war comes and reveals the decay of Eu- rope&n culture, he still bas a eurse for the old world. “Not from the West,” he exclaims, “will the sun appear!” The poet was not mistaken, As the November revolution appears with its savage- ry. and brutality, its tremendous force of destruc- tion, it does not frighten Blok as it does so many of his colleagues who lament the destruction of the workd and the passing of all human culture. On the contrary, what the others look upon as the greatest crime, Blok sees ag the highest vir- tue. What to others sounds like the most ter- rible discord is to him % wonderful symphony. Such a symphony is the November revolution, as he explains in one of his admirable articles. But in order to understand the whole significance of this expression, it is necessary to grasp fully the poétry of Blok. Bandelaine, the French poet, once ‘said. that the words which are most frequently repeated by a poet are the truest reflection of his crea- tive impulse. In Verhaeren’s work we encoun- ter most frequently the word “red,” and redness is indeed the special quality of Verhaeren’s poet- ry. Blok repeats most often the work “music,” and the idea of music is the dominant character- istic. of his poetical perception of the world. Every phenomenon reveals itself to Blok in musi- cal terms. Thus he develops the theme of the inteHectuals and the revolution, because for him music is the sublime harmony between man and nature, the supreme expression of the human spirit. It ts in musical terms that Blok develops the theme of the November revolution. Moreover history, he declares, has been so full of mmsic, Love, he says, works wonders. Music charms beasts. This love and this music have been cre- ated by the revolution. Thus Blok pleads with intellectuals who believe that Russia fs being crushed ‘under the heavy boot of the Twelve. “Music is spirit, and the spirit is music. The devil himself once commanded Socrates to fol- low the spirit of music. With all your body, with all your heart, with all your consciousness, heark- en to the revolution!” What is it then, that expresses the music of the revolution? It is the heavy tread of the Twelve, the new apostles who crush everything in their power, who destroy and are themselves destroyed. They roam in the dark of night over deserted streets, haunted by the ghosts of death and bloodshed which echo with the shots of their own guns. One of them, intoxicated by his own power, shoots his sweetheart. But he does not pause. Weigged down by sorrow, lie goes on his way, for “There’s no time to nurse you mow, Your poor trouble’s out of season. Harder loads won't make us bow.” And when the tragedy of this wild apostle Teaches its climax, he cries out, choked with grief: “Fly like a bird of the air, Bourgeois! I shail drink to my dead little dove, To my black-browed love In your blood.” It is the expression of his own hatred, und of the hatred of all those who have been prey to exploitation and injustice. This poem reveals the whole chaos of the revo- lution, which, striving to bring happiness to the world and make an end to crime, itself commits crime. But how else is it possible to get rid of that “leprous hound” which is Blok’s symbol for the old world? Everywhere is emptiness and barrenness, the result of civilization. “A bourgeois, lovely mourner, His nose tucked’ in his ragged tur, Stands lost and idle on the corner, Tagged by a cringing, mangy cur. The bourgeois, like a hungry dog, A silent question, stands and begs; the old world, like a kinless mongrel Stands there, it’s tail between its legs.” And inthis emptiness and barrenness, amid the ruins and the graves, “Our boys went out to serve, Out to serve in the Red Guard, * Out to serve in the Red Guard, To lie in a narrow bed, and hard.” And the wild shout of the boys rings true: “A bit of fun is not a sin, There’s looting on, so keep within, ‘We'll paint the town a ripping red, Burst the cellars and be fed.” Here is the powerful eruption of the popular wrath, the bloody work of the revolution, which recognizes no barriers. It is the thumder-music of the wild world-storm, that rises in the East and sends its shout reverberating to all the ends of the earth, announcing the advent of “Freedom, oh, Freedom, Unhallowed, unblessed,” And strangely enough, at the head of the Twelve, drunk with blood and profanation, “In mist-white roses, garlanded— “Christ marches on. And the Twelve follow.” { cannot be otherwise. The sinful, wanton Mary has become holy, she has given birth to a God. The wild Russian people have purged its soul in the suffering of centuries, It has aveng- ed itself for its wrongs, and become the standard bearer of the greatest human idea. To Blok this (Continued on page 7) rs -