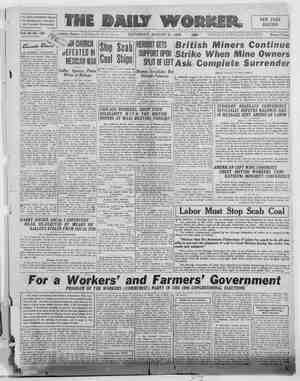

The Daily Worker Newspaper, August 21, 1926, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

ss ete, History of the Catholic Church ; in Mexico By Manuel Gomez. CHAPTER II. The Church as a Religious Institution. NLY one other thing is quite as absurd as the holy protestant big- otry of the ku klux klan, and that is the appeal of the Roman catholic church for “religious toleration.” Rib- tickling as such an appeal must be even to Americans, the full humor of it can be appreciated only in a “cathol- ic country” where the church has had its hour of domination. The catholic church emigrated to Mexico in the first quarter of the six- teenth century and on November 4, 1571, the tribunal of the holy inquisi- tion was established in the City of Mexico. Under the joint reign of Spanish viceroy and catholic arch- bishop “religious toleration” was a high crime, punishable by the most se- vere penalties. In the year 1649 his- tory records that 106 people were burnt to death in one day by the in- quisition for holding religious views somewhat at variance with those of the catholic episcopate, Thruout the whole period of Span- ish-ecclesiastic rule the laws of the land forbade the exercise of any re- ligion other than the Roman catholic. Mexico secured her independence’ from Spain in 1841, The priests were in the saddle again, however, and the first constitution adopted declared: The religion of the Mexican state shall be the Roman catholic apos- tolic to the exclusion of any other. “Submission to Authority,” the Cler- ical Slogan. As a matter of fact the church could not be considered in any other way than that of an institution for the maintenance of authority. This authority might be called “religious” providing we understand that the church conceived of religion as linked up inexplicably with a definite social order—one in which the supreme vir- tue to be inculcated was obedience tp constituted authority. The church and the semi-feudal state, the reactionary state, the state of the landed aristocracy, were bound together in a single religio-political hierarchy. Not only did the clergy enjoy the vast economic and “spirit- ual” powers indicated in my first chap- ter, but also certain privileges which protected them from the reach of such civil law as there was at that time. These privileges, which were termed “fueros eclesiasticos,” exempted the priesthood from retribution at the hands of the civil courts for any erimes committed by them. When spe- cial taxes were decreed the church was, of course, exempted from them, in spite of its great possessions, It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that the catholic historian, Zamacois, was enabled to write that “more crimes against the civil authorities were headed off thru the medium of the confession box than thru any other agency.” As the years went by catholicism in Mexico did not become any more tol- erant. Under pressure from liberal forces the church sometimes adopted new machinery, but its method re- mained the same—brutal suppression of any liberating tendency. In 1853 the head of the clerical party ad- dreased a communication to President Santa Ana, in which we find, among other things, the following: Advice to the President. We do not care, as some papers have said in order to discredit us, to establish the inquisition nor reli- gious persecution, but it is under- ‘stood that the duty of the public authority is to prevent the circula- tion of impious books. .. . Under the leadership of the clerical party Santa Ana’s administration pro- mulgated the so-called “Lares Law,” by which every publisher of newspa- pers, books or pamphlets were com- pelled to place with the government a bond of not less than $3,000 to be confiscated at discretion for offenses against the ecclesiastical or civil authorities. The law proceeded to de- fine such offenses as: Attacks upon the dogmas of the church, or expres- sions of doubt in regard to her creed; and criticism, however slight, directed against the government or of its of- fiers. It likewise established a secret tribunal to deal with violations of its provisions. «Fhe -operation ,, of,, this measure immediately suppressed the liberal newspapers El Monitor, El In- structor Del Pueblo, El Telegrafo and Bibleoteca Popular Mexicano. It will be obvious by now that this “purely religious institution,” the cath- olic church, at least interpreted re- ligion in an extremely loose sense. The present exican government, which has pr/iibited attacks on the government by clerical publications, understands that interpretation very well, and is acting upon it. There can be no other interpretation, Ceremonies, Mysteries and Legends. If, however, with “christian” for bearance, we manage to isolate those activities of the church directly con- nected with the so-called spiritual world, we are confronted with such a degrading confabulation of mumbo- jumbo that we cannot fail to look for ulterior motives even here, Every church in Mexico had its miracle and every cathedral at least a hundred of them. Legends were—and still are— assiduously circulated, of peopie who had been raised from the dead thru the intercession of the catholic church. Lepers were cured and the blind were made to see. And all this as a re- ward to “the faithful” for their patient allegiance to the Roman catholic church, The overawing ceremonies of the church, embellished with Aztec pagan mysteries in the most cunning theatrical fashion, are still in vogue at the present time; but in the nine- teenth century they constituted a veri- table orgy of human debasement. All of these spiritual exercises served a single purpose: to fix the authority of the catholic hierarchy be- fore the powers of this and all other worlds, and consecrate the very prin- cipal of authority in all forms of life. Consequently, the “purely religious” attributes of the church were the most dangerously reactionary of all its at- tributes, But we have already sufficiently in- dicated that the influence of the church was by no means confined to these fields. As late as 1863 the pious Pope Pious IX addressed a mandatory letter to Maximilian, then about to begin his brief masquerade as emperor of Mexico, I A Letter from His Holiness. “Your majesty Is fully aware that “THE LOVER'S DREAM.” “MM\HE Lover’s Dream” is a Chinese produced film made and acted by Chinese in Shanghai. The technic is bad. The acting is different from our western standards. Yet it is an ex- tremely interesting picture. I saw it in Chicago Chinatown, I dont think it will ever be handled by any of the regular bookers. The only way you can see it is to watch the movie house in your city nearest to Chinatown, if you have one. I take it that the producers, the Great Wall Film Co. of Shanghai, made the film for profit. But there is also propaganda involved, and my impression is that the company must have been formed by a group of na- tionalists in which students predomi- nated. The plot of the story so far as the love part of it is concerned is adapted to the oriental modes. The lovers in this case happen to be husband and wife. Such a scenario would make a Hollywood producer throw several cat fits—but, as I say, this film was produced in Shanghai, It is also notable that there is abso- lutely no kissing. After a three-year absence in an American military school the hero comes home and shakes hands with his mother and his wife. It’s rather hard to get around at first, but you simply must get to understand that people don’t kiss each other in China, The hero enters the army of his nrovince. He is colonel of a regiment, He introduces new methods. The army, or his section of it, is turned at once into a school and workshop. He is making progress when war is declared with another province, At a military council meeting prior to the declaration of war our hero tells the provincial war lord what he thinks of the impending campaign: that it is needless and criminal. This gets his stripes taken away, but re- turned again thru the intercession of a powerful friend. He goes to the front, His farewell to his family is touching—in spite of the lack of kiss- ing. In camp he still broods over his family and the war, Two soldiers stand in the shadows. One says to the other: “Do you know what we are fighting for?” The other says: “No, do you?” The reply comes: “I know only we were told that if we did not go to war we would starve.” The colonel, our hero, overhears this ‘and pities the poor soldiers, In the very first engagement he is wounded. In his dream he sees his wife and mother and child. Then he dies. The news is broken at home and the family stricken with grief. In the evening the wife sees visions of the deceased husband. And that’s the end. Despite its defieiencies, the pro- jector flicker of ten years ago, the badly translated titles (they were in both Chinese and English), in spite of these, the uniqueness of an all- Chinese film, the anti-militarist prop- aganda and the peak it allows of real Chinese life are worth while. T.L. | _ WEEKLY PICTURE SUMMARY | “Moana”—Beautiful—See it! “Battling Butler”—Buster. Keaton in “a half-baked knockout” says G.W. “The Son of the Shiek”—(With Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky) Hot pappa on the burning sands. “Padiocked”—According to G. W., it is “one of the epidemic of moral- istic pictures,” with Lois Moran. “La Boheme”——“With John Gilbert, Lillian Gish and Renee Adoree, La Boheme is as good a production in its own kind as the “Big Parade,” says A. S. That’s saying a great deal. “The Road to Mandalay”—-My gawd what they put Lon Chaney in! “Mantrap”—“Was peculiar because it really had some good points,” G. W. points out. Ernest Torrence in a Sinclair Lewis story, “Variety”—“Different and good with Emil Jennings a good actor,” ac- cording to “Smaxico.” in order effectually to remedy the wrongs committeed against the church by the recent revolution (Juarez’s liberal reform movement) and to restore as soon as possible her happiness and prosperity, it fs absolutely necessary that the cath- olic religion, to the exclusion of any other cult, continue to be the glory and support of the Mexican nation; that the bishops have complete lib- erty in the exercise of their pastoral ministry; that the religious orders be reorganized and re-established ac- cording to the instructions and pow- ers that we have given; that the estates of the church and her privi- leges be maintained and protected; that none have authorization for teaching or publication of false or subversive documents; that educa- tion, public or private, be supervised and ted by the ecclesiastical author- Ities, and, finally, that the chains be broken that until now have held the church under the sovereignty and despotism of civil government.” Thus it will be seen that it has been the consistent policy of the church to use state and other instruments for political purposes and for its own re- actionary privileges. This policy con- tinued when it was not contravened by liberal opposition right down to the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20. Juarez succeeded in breaking the of- ficial union between church and state once for all, but I pointed out in the first chapter of my narrative that many clerical privileges were regained under the long dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. Openly and with the sanction and might of the governmental ma- chine behind it where possible, by stealth where necessary, the church maintaing its stand for specia) privi- lege and reaction, It has never ceased to struggle for the right to hold vast , and even at the present moment is engaged in open rebellion against the Calles government largely to this end, Such is the record of the catholic church in Mexico as a religious insti- tution, with its ubiquitous religious ties feeling into every nook and cranny of the socio-political organism, Toleration»for What? Be not deceived by double-chinned catholic millionaires who have organ- ized the “League for Defense of Re- ligious Toleration” to carry on a strug- gle against President Calles. Nor be mislead into the naive false liberalism expressed by such a commentator on Mexico as Carlton Beals, who writes: The church in Mexico, if it is to be of national service to a stricken peo- ple, must, like St. Francis, divest Itself of its wealth, its material power, and its luxury, and regain its spirit of self-sacrifice, self-immola- tion, and the desire to serve. Vain hope! How can the church regain characteristics it never had. With the record of the church before us such sentimental phrases are the merest drivel, and, moreover, they serve as indirect support to the cleri- cals in helping to perpetuate a false tradition. In Mexico, as everywhere else, the catholic church fights for dominance. It is as tolerant as it has to be. At the present time it is calling for tol- eration. Toleration of what? For the right te establish parochial schools— which means for the right to fill chil- dren’s heads with reactionary clerical bigotry. For the right to carry on political agitation in counter-revolu- tionary ecclesiastical organs, For spe- cial catholic privileges and attributes, (Next week’s installment of the “History of the Catholic Church In Mexico” will expose the record of the church In opposing every suc- cessive move toward Mexican po- litical progress from the Spanish colonial period to the present day.)