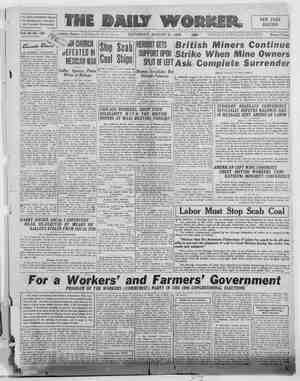

The Daily Worker Newspaper, August 21, 1926, Page 13

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

~ munity of Fruitlands, Y ey worker does not appear in American literature in other than a lowly and obscure figure, until after the Civil War. Before that time it was the hatred of the Negro slavery and the lure of bourgeois utopias that consumed the energies of the liberal artist and reformer, The Abolitionists were as senti- mental as the utopians. The Aboli- tionists, for instance, found the en- slavement of the Negro so hideous that the bondage of the white worker almost entirely escaped their atten- tion. Few more sentimental and in- artistic novels have been penned in America, for example, than “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” The social influence of the book, however, was very deep and widespread, As a result of the revolutions in Europe during the first half of the nineteenth century, and the bourgeois theories of Fourier, who outlined a utopian society that even the bour- goisie could adopt and applaud, the American liberals tried to revolt against the prevailing order by found- ing “Fourier colonies and retreats. These literary and philosophic liber- als, then viewed as _ revolutionists, were usually known under the name of Transcendentalists. In the words of Emerson, who was their leader, in- dividualism was their goal. Trans- cendentalism was a form of mystical individualism. Its practical aspects, curiously enough, turned toward the task of realizing utopias. Two experi- ments of theirs, then known as radi- cal, are remembered for theif fasci- nation and futility. One of these ex- periments was known as the com- which was founded by Ann Bronson Alcott, who was the father of the famous and popular Louisa May Alcott, and two English friends. The Fruitlands was an odd experiment at co-operative en- deavor. It was a miniature Utopia which had all of the rigidities of a regular state. The diet was purely vegetarian; ven ;milk and eggs were excluded, and water was the only drink permitted. Only vegetables that project their forms into the air were eaten; potatoes and beets that para- chute their forms to the earth were taboo. The winter, chilling enthusiasm and destroying production, brought an end to the venture. The Brook Farm experiment was the other. Both ex- periments are famous as attempts of liberal esthetes and discontents to escape the bourgeois world of compe- tition. George Ripley, a Unitarian minister, was the leader in the Brook Farm project, but it was Nathaniel Hawthorne and Margaret Fuller, vis- {tors rather than participators, who gave it the romance of rich personal- ity and the enchantment of the beau- tiful ideal. In “The Blithedale Ro- mance” (1852), one of the interesting novels that Hawthorne penned, the career of the Brook Farm colony is pictured, Altho in places the picture may be tinctured with exaggeration, it is revealing of the mood of mind of these bourgeois reformers and ideal- ists. > te? Thus it was in the avenues of Negro slavery and bourgeois utopias that the spirit of artistic protest expressed Labor and Literature itself in the days before the Civil War. Cooper had written of rainbow-plumed Indians that danced like phantoms thru the pages of wild Tomance, Brown had told of the horrors of ventrilo- quist and hypnotist, Kennedy had haloed the colonial days of Maryland and the Carolinas, Simms had roman- ticied the sunny clime and merry tra- dition of Dixie, and Poe had cultivated the morbid, but in the work of all these there was no more social pro- test than in the skits of Van Vechten and the homilies of Frank Crane, It should not be thought that these literary radicals of that day were weak, resistless types. They were part of the individualism of their time and yet in revolt against its grosser aspects. Their heroism, which. was real heroism then, is today but an amusing gesture. Thoreau’s going to jail rather than pay his taxes, Emer- son’s refusing to pray and administer the Lord’s Supper and consequent res- ignation from the ministry of his church, Alcott’s closing his school rather than exclude a Negro student, Parker’s risking his life in the anti- slavery panic—all these were expres- sions of sincerity that can be appre- ciated only by understanding their his- torical background. Yet these men had no conscious- ness Of the position of the white worker, in the growing capitalist so- ciety of that period. While the work- ers were publishing several] dozen la- bor papers expressing protest and de- manding change, these bourgeois ideal- ists were content with colonies for dream-children and distressed philoso- phers. After the Civil War, however, things changed. With the organiza- tion of the Knights of Labor in 1869 scattered class protests began to co- here into a united class attitude, In 1877 the socialist labor party had come into existence, and in 1892 it made its first nation-wide ,campaign. The American worker, driven more and more to the defensive in this pe- riod of the expansion of large indus- try, was organizing himself in ways of definite protection. By 1886, for in- stance, the Knights of Labor had a membership of over 700,000. With the great strikes in additiog it was a time of intense excitement and struggle. UT of this class struggle came the first book of the workers, Bel- lamy’s “Looking Backward.” In this novel, as well as in “Equality,” an- other novel by the same author, we find an open rupture with the old or- der and a striking if somewhat fanci- ful picture of the new. While the christian socialist school in England was sentimentalizing the proletariat, Bellamy was trying to realize its am- bitions in a social order that he con- ceived and dedicated to the future. We must remember that in English novels such as “Mary Barton,” by Mrs. Gaskell, and “Alton Locke,” by Kings- ley, the proletarian had become an ac- cepted and sympathetically portrayed figure in English literature. Senti- mental tho their approach may have been, the coming of these nhovels marked a different trend than the aristocratic and bourgeois that had preceded. In “Mary Barton,” for ex- ample, were passages such ag this: “Don’t think to come over ie with th’ old tale, that the rich know nothing of the trials of the poor; | say, if they don’t know, they ought to know. We're their slaves as long as .we can work; we pile up their fortunes with the sweat of our brows, and yet we are to live as sep- arate as Dives and Lazarus with a great gulf betwixt us; but I know who was best off then.” Bellamy extended their protest into @ program. In the framework of “Looking Back- ward” was impaled the delieate and complex framework of the new so0- elety. The projection of this new s0- clety was placed at the remote date of 2,000, but the hurly-burly of change that was in the air made the readers of the novel conceive it as an ap- proaching and close reality. Not many years before, it must be remembered, Marx was contributing to Greeley’s New York Tribune, and, not many years . De Leon, with many other socialists, was preparing the way for of the class revolution. Just two years before Bellamy’s famous novel came out a union labor party was or- ganized in Wisconsin and a similar party was begun in New York with Henry George as its candidate for mayor. The atmosphere wag vibrant with discontent and protest. In re- sponse to the excitement caused by “Looking Forward,” Bellamy societies were formed in cities and towns over the country and discussion groups everywhere grappled with the problem of.. social..reconstruction,.....uater the book became a kind of basis of faith for the nationalist party. In Bellamy’s society there were “no longer any who were or could be richer or poorer than others, but all were economic equals. He learned that no one any longer worked for another, either by com- pulsion or for hire, but that all alike were in the service of the nation By V. F. Calverton working for the common fund, which all equally shared, and even neces- sary personal attendance, as of the physician, was rendered as to the state, like that of a military sur- geon. All these wonders, it was ex- plained, had very simply come about as the result of replacing private capitalism by public capitalism, and organizing the machinery of produc tion and distribution, like the politt- cal government, as business of gen- eral concern to be carried on for the public benefit instead of private gain.” Bellamy, however, with ‘ali of his 4 vision, was a sentimentalist. In his attitude is something of the spiritual- ity of a Jesus instead of the courage of a Liebknecht. Yet it is to him that we must turn for the first literature in America that was devoted to the proletariat. While pamphleteers and labor leaders had long stood for the social revolution, the artist had been silent. Bellamy was the first to break this silence, The Golden Highway what seemed to them the rapid col- lapse of capitalism and the beginning Lift up your voice and heed him! Who shrinks from sto secret blade? ~ + By GEORGE JARRBOE, Whose wills may journey out and on. Cowardly Manhattan shuddering under stone, The blithesome wanderer shall know no more, But envy him the sunlit, ever-youthful shore. “How may I start? Where lies the morning road? I falter, I break with hunger and the unequal load. Efficiently falls the lash; in dirty street My co-slaves spurn me with their bleeding feet!” sing the way of Freedom. Swiftly the servilest slave will strain his chains and | Ging the art of the rifle, the trick of the bayonet. Sweet is the dawn road when the steel is red and wet! Who dreads a bit of a halt to storm a barricade? p at the scaffold, the end by a Your goal the towers of Freedom, in the child-land afar, And if you fall to shine on Humanity’s night a star. What better road for heroes than the strife, For the great weal of human life? For the sunlit commune over yonder And tearless cities filled with happy wonder? Farewell, Manhattan! The last slave-song is sung. We go to join the armies of the ever-young. Always the lily and rose on either hand, The dawn, the silver bells of fairyland. on etl ts dsl AT. st nl a lh ae pe en et ttn, A te BD ili tinal ta tit met ts th ntti ti a