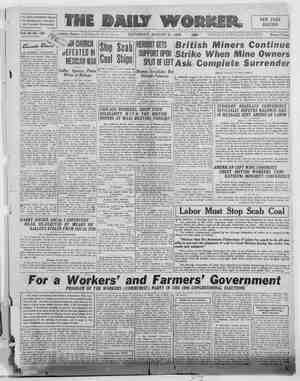

The Daily Worker Newspaper, August 21, 1926, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

— The Trumpet OW fine the sun shines; hospital-garden, the bench over there. I am not to call you “comrade”; you are no “damned Red”; are a “respectable citizen?” It seems to me, your back is bent like mine, your hands are hard, and worn like mine, out of your face speak. hunger and misery, as out of mine, Haven’t you ‘slaved away an entire life, labored, so that others could revel, suffered want, so that others could ca- royse? You nodded. Then aren't we comrades, mates? Hasn't the same mother, Distress, given birth to us? The same prison of misery confined us? Are we not dying of our common poverty, alone, deserted, here in the hospital? And I am not to call you “comrade”? Well, well, let’s not talk about it; I don’t want to prévoke you. How gloriously the sun shines! [I feel so, light and joyous today. I believe itis because I have dreamed of my little trumpet. You think I oughtn’t to speak so much, it harms my throat? The few mionths that I still have to live, it will last all right. Move up a little closer, so that 1 can talk very softly. I must talk once more before I am silent forever. You! ask what it has to do with my little trumpet? Tat isa long story, is really the story of my life. As a little lad, I had, for a long time, wished for a small trumpet. My God, how I wished for it! To blow out into the world once, just out of pure joy, with a voice which all, all must hear. At Christmas, mother presented me with a small, tin trumpet. How laboriously she must have scraped to- gether her pennies, the poor soul. A charwoman can- not afford to grant her child a joy, without paying for it with her own suffering. I was Diissful; how the trumpet glittered. I took it out of my mouth so I could view it better, and quickly put it between my lips, because I longed to hear its sound. I felt as if the entire world belonged to me. The next holiday, my mother went to clean a gentle- man’s rooms. I went along, for it was bitter cold in our home and there, at the gentleman’s, it was al- ways warm and comfortable. I waited in the ante-room, mother enjoined me not to blow on the trumpet, the gentleman couldn’t bear amy noise, | sat demurely in a comer, fondied the glittering, trumpet, was very happy. Then, however, the wish came to me to put the trumpet in my mouth. I don’t want to blow it, you know, merely want to feel the trumpet between my lips, to experience the queer-delightful taste of tin. 1 searcely dared to breathe. Suddenly, however, I don’t know how it happened, a shrill sound pierced the air. An angry voice shouted from the adjacent room: “Quiet! What's that abominable noise?” I was so frightened, that I began to tremble. Grad- ually, however, defiance took possession of me. “Albom- inable noise!” My beautiful, beautiful trumpet. I put it to my lips, drew a deep breath and blew with all my strength into the opening. The door of the room was torn open; red with anger, the gentleman dashed out, tore the trumpet out of my hand and broke it. \My breathing stopped, the whole world seemed to fall in ruins. The gentleman disappeared. Crying, I put the trumpet to my mouth, tried to blow: not a single wee sound. The gentleman, clad in a magnificent fur, stepped into the ante-room again, walked past me and out thru the door. I got up softly, spied into ‘hist room from which the gentleman had come. I saw many splendid. things thru tears, pictures and pillows and sparkling objects. My blood grew hot: “The man has everything, every- thing; but I had only a small trumpet and he ‘has broken it.” I did not get another. The broken trumpet lay home on the window sill, and at times I stroked the glitter- ing metal, which no longer carried any sound within. | We staryed on and froze for years. I went to’ the factory—-you know yourself what that means—grey, weary mornings, which merge into grey, weary eve- nings, one’s ears full of noise, one’s eyes full of ugli- ness, the body eaten up with exhaustion. Then suddenly my view opened out into a bright world, a world in which some will not be the pack ani- mals of others, in which there will be freedom, bread, and joy, sufficient for all. 1 became a socialist, Whenever I looked upon the comrades in the fac- tory, their dull hopelessness, their’ tiréd resignation, then everything flared up within me. They do not it even animates the sad Come, comrade, let’s sit down on even know that they are human beings, with a right to | life and happiness, like the others to whom the world belongs. They are blind, unable to realize that power could be theirs, that they are many, an enormous mass against a small number, One needs only explain it to them, find the right words, cry out the truth into the world until it penetrates to the deafest ears and wak- ens to life hearts entombed in misery, was glad about the warmtlr dda’}f BY HERMYNIA ZUR MUEHLEN. (Translated by A. Landy) But how is one to find the right word? My thoughts welled up. within me, bubbled, strove upward; but when I wanted to express them, dead, empty words came, toneless, soundless, as out of my little trumpet when the gentleman had broken it. I had learned nothing, I knew nothing. Nor could I learn anything. My poverty. condemned me to eternal ignorance. And is it not strange, comrade? On my way to the factory, I went past schools, the university; there, in those buildings, knowledge for which I longed, lay stored up and I could not attain it. Othérs could, en- ter, could receive the gift of knowledge, I, however, had to hasten by, to the machine, : My body was weak, but my spirit was fresh and active, quick of comprehension. Those who had taken everything from me, one thing, however, they. had not been able to take: to take from me the power of my brain... But it lay. fallow;, the only thing I possessed lay fallow, because the others, who had everything, rendefed my gingle possession worth- less. I did not want to let myself be conquered; I learned and read, sat nights over the flickering candle, devour- ed the new, the longed-for knowledge. And now when | spoke to the comrades, a word did, at times, penetrate to them, pricked them awake with a fine needle point, roared in their ears; suddenly ani- mated eyes answered me, At a meeting, my tongue loosed itself completely. I cried our distress, our misery, the suffered injustice, out into the world; showed the comrades the life of the others, that life of joy and beauty which is built upon our dead lives. I felt as if my voice rang shriek- ing thru the entire world, called to battle like the crash of trumpets, to the one, jist, sacred battle. Great, blissful joy completely filled me; mine is the instrument with which I herald freedom; my. poverty and my misery, my love and my hate have built it; those who have robbed us of everything could not rob me of this. Many, many years ago a small boy had a pare shabby trumpet. A wretched little happiness which the rich gentleman broke for him. The enslaved worker, the pack-animal of the rich, had his Joy¢ and ,his -knowledge—certainly I acquired it just as painfully as Once my mother her pennies for the little trumpet—he had a voice with which he could herald truth and justice—and the gentleman who pos- sesses everything, broke it for him. I had spoken all too loudly, the sound of my words had penetrated too far, had called an echo into life. This could not be allowed. I was thrown into prison. When I came out again, sickness sat in my throat and ate at my voice, The words lay ready in my mouth but could only soar out hoarse, rattling, and incomprehens- ible. That which burned and blazéd within me ‘had. be- come mute, like the tin trumpet into which the little | boy had blown in vain; and for the man, the entire’ world fell in ruins as it had once fallen in ruins for’ the child, You don’t understand me anymore, I should not speak on? I still want to tell you my dream, comrade, |then I'll be silent. Last night my little trumpet extended a hand to me and a Voice spoke: “Blow into it!” I, however, sadly refused it and replied: “It is broken.” Then the voice answered: “Endless misery and unutterable tortures have restored to the mute instrument its sound; the injustice which weighs upon the world is so great that muteness itself has found a yoice. and cries out to the skies, Take the trumpet and blow!” . Doubting, I obey- ed, placed the ‘trumpet to.my mouth and. blew into it. ‘A sound. resounded; so overwhelming; so powerful that I was almost frightened. All the wretchedness of the enslaved, all the lamentations of the tortured, all the despair of the world shrieked out, screamed, roar- ed, penetrated stone walls and prison barriers, whipped dead hearts and benumbed souls into life. I thought of the trumpet blasts of the Last Judgment and I knew that now the World Judgment is approaching; but not a hidden God from blissful heights is calling the world before his judgment chair; the judges are we, the op- pressed, the disinherited, the robbed, we, the people of the whole world. " Let ‘us go into the ‘house, eokinreuael!* ‘The sun is not shining any more. 1 am cold ‘and r ave srown tired; .the French marine works on the cruiser. , put his O. K: on the’ meat. - ship’s doctor, Smirnov, taste the -“borsht,” By M. A. SKROMNY. “We are not the fighters, ~ “We are just their shadow”... “itn V era Figner, iy happened over two decades ago, Defeated by the Japanese in the war in the Far East, bleeding and tortured by the tools of the autocratic czaristic gov- ernment, Russia was beginning to boil with revolt. The revolutionary movement was growing and spread- ing. It had a strong foothold in the south, especially in Odessa, the biggest sea port of the Black Sea, where there were many big factories. There were strong revolutionary organizations jn many factories and also nuclei among the Black Sea sailors, The Black Sea fleet had its base at Sebastopol. In every one of the battleships there were groups of revolutionists and in the woods near the city, meetings of revolutionary sailors were held from time to time. On June 12, 1905, the Armored Cruiser Potemkin Tawrichesky left its base at Sebastopol for practice near the island Tendra, There were 20 officers, 12 conductors, 760, sailors and 20 marine workers from They had aboard 30,000 poods of coal and 10,000 shells. As aid to the cruiser there was sent along the mine sweeper No. 267, Among the Sailors there was an organized revolutionary group of about 100. They were ready for revolt and. the Sebastopol revolutionary city commit- tee passed a motion-Péquesting,; them-to -wait, paxil the end of the practi¢a ptriod) "They agreed srr sr * On June 13 in the morning the cruiser and the mine sweeper arrived at their destination. About noon time the mine sweeper was sent to Odessa for provision. The sailor Shenderov, a social-democrat, with the ex- cuse of going to the post-office to get the mail, went to the city to get connections with the revolutionary organizaions. On the same day’a general political strike began in Odessa, The workers’ delegations, who were sent to the city officials.to present the. demands of the workers were arrested. Protest meetings arranged by the work- ers were fired upon by the police and soldiers. On the next day, June 14, thé workers attémpted to storm the police stations in order to liberate’ their arrested com- rades. There was more shooting and more killed.’ ‘In the meantime the mine sweeper bougiit provisions including stale meat.” The doctor of the mine sweeper When the meat was put aboard the cruiser on June 14 it was rotten and om of worms, The storm began to gather. The next day, on June 15, the sailors refused to eat their dinner. They ate only the bread and drank the tea, refusing to touch the “borsht.” All the sailors ‘except: those’ who =were tending the machinery’ were lined up on the deck. The armed guard was called out. The commander had the He | de- clared it fit for food. Golikoy began to swear threat- ening to‘shoot all who are dissastisfied. baat “Those that are satisfied, step forward!” demanded the commander, A few wavered and stepped forward. Then more followed; and more. When only about 25 were left Golikov crossed their path exclaiming: “That will be enuf, we will now teach you all a son.” les- He then ordered the guard to take all the mu- It ‘was rotten.. When the commander of the cruiser, ‘Golikov, heard. wbout it, he ordered the” drummers" to beat general» - assembly.” DZERZH By EUGENE KRE You are gone... But life will follow the road of life, For it is eternal, | cry not, that you are dead, For death is a part of life, And both—the coming and the going Germinate the living force, Yet I grieve eee And am happy In my grief