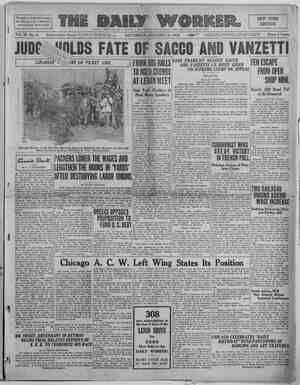

The Daily Worker Newspaper, January 16, 1926, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

mee au en ree By GERTRUDE WELSH. (Research Department, W. P. of A. Were else in the United States is the victimization of con- sumers by means of monopoly-fixed prices carried on with such extensive- ness and such smccess as in the slaughtering and meat packing indus- try. This industry cannot be equalled for the number of products, by-prod- ucts and services held under control by the fewest possible capitalists. Tem years ago, these few were the “Big Five” companies of Armour, Swift, Morris, Wilson and Cudahy. With the purchase of the Morris firm by the Armour interests in 1923, they became the “Big Four.” Latest news on the subject, however, (February, 1925) re- duces the “Big Four” to the “Big Two,” Armour and Swift, whose com- panies together slaughtered 47.7 per cent of the total number of animals passed by federal inspection in 1924. “Big Two” Control Food Prices. Along with this increasing concen- tration of control in the meat packing industry has come an expansion of activity that has made the “Big Two” predominant not only in this field, but in almost every field of food produc- tion. Factors that made possible the growth of the packing industry and its easy manipulation of prices by a handful of men were equally effective in bringing other industries under their domination. Their vast distribution system of refrigeration and “peddier”’ cars, with the advantages arising from private car lines, icing stations, cold storage plants and a net-work of branch houses, not to mention the control of real estate sites, of banks, of trade percidicals, as well as of stockyards, made possible their invasion of the wholesale “grocery trade. In one year, the four packing firms, but more especially Armour and Swift, sold over $2,000,000,000 worth of groceries. Strategic Points Occupied. As many as 674 different articles of general utility were enumerated in a list published in 1919 as commodi- ties distributed by the five largest packing companies. Included were such diverse products as Coca Cola and fence posts, curled hair and Red Dog flour, molasses, musical strings, potash, putty containers, tallow and tile. Especially, in the field of meat sub- stitutes have the big packers strained themselves to occupy strategic points, to such an extent that they have an- nuaily handled, for instance, over one- half of the interstate commerce in poultry, eggs and cheese,—and play a leading part in distributing canned vegetables and fruits. Dictatorship of the Packers. Among the companies in which the big packers have obtained interests large enuf to be dictatorial influences are the’ cattle-loan companies which make the necessary loans to growers and feeders of livestock, and railways and private car lines transporting live stock and manufactured animal pro- ducts, as well as most important stock yards and cold storage plants. They are interested in banks from which their competitors are forced to borrow; in companies supplying ma- chinery, ice, salt, materials, etc.; they are the principal dealers on the pro- vision exchanges where future prices in animal products are determined; they or their subsidiary companies deal in hides, oleo, etc., even purchas- ing these by-products from the small- er packers unable to carry on their manufacture, From rendering fats from what would otherwise be wasted in their own factories, they have reached out to secure the waste fat and bones in local butcher shops in large sections of the country. In some instances, they are even interested in companies fulfilled within two years, contracting for the disposal of the garbage of large cities! Packers and Bankers Fuse. As meat-packing is the largest in- dustry in the United States both as to the value of its raw material and the value of its products, banks are espec- jally important to the packers. And on the other hand, because of the quick stock turn-over and the enorm- ity of profits, meat packing is of tempting interest to bankers. So the fusion of banking capital with this in. dustry’s capital is pronounced. It is estimated that the “Big Two” own stock in or are represented on the directorates (thru relatives or person- ally) of at least 74 banks, with capital aggregating almost $4,000,000,000. These include Wall Street’s bulwark, the National City Bank, of which J. Ogden Armour is a director. Besides this, some of the most pow- erful groups in the country, the Chase National Bank, Guaranty Trust Co., Kuhn, Loeb and company, Wm. Salo- mon and company and Halligarten and company now own the Wilson pack- ing firms, warmly welcom2d by both Armour and Swift, who are said to have remarked that this arrangement is “most satisfactory.” No Limit, Says U. S. Report. “There is virtually no limit to the possible expense of the big packers’ wholesale merchandising short of the complete monopolization of the primary distribution of the nation’s food,” according to the statement of the United States federal trade commisison in 1919, This statement came as the result of the last of a prolonged series of costly, exhaustive government inves- tigations of the meat. packing indus- try. The “Big Five” packers at that time were judged guilty of a gigantic conspiratorial combination in re- straint of trade. Definite recommenda- tions were iiade that Whe government acquire the ownership of the means of transportation, storage and market- ing held by them, leaving only the slaughtering houses in their hands. Added to this was the proposal that municipal abbatoirs be opened as soon as practical. Six volumes of incriminating data (under the Sherman anti-trust laws) were gathered by the commission, suf- ficient to make claims of “free compe- tition” smell as bad as did the spoiled beef the packers sold the government for its soldiers, despite the fact that it was given an acid bath. U. S. Government Lends a Hand. And the packers likewise “sold” the government as far as the investiga- tion was concerned. As might readily be imagined, the government did not attempt to carry out the commission’s recommendations, which practically instructed it to monopolize the meat- packing industry,—but allowed itself to be monopolized instead. As a re- sult, almost every action of congress, of the department of agriculture or of the supreme court since the report, has been of such benefit to the big packers that they couldn’t have pros- pered more if they themselves had been the government, “Punishing” the Packers. However, certain legal motions of “spanking” the packers were pomp- ously performed by the supreme court in order to deceive the public into the belief that it had”been “saved.” Feb, 27, 1920, the U. S. attorney general filed with the court a petition alleg- ing unlawful combination between the “Big Five” and asking “relief.” In reply, the packers entered a “consent” decree, in which they agreed to dis-combine, but stipulating that their offer should be understood as coming from persons “innocent” of combination. “The keenest competi- tion exists between us,” they asserted, Certain steps believed necessary by the attorney general to unscramble the packers’ omelete were-outlined, em- bodying requirements supposed to be From the “Big Five” to the “Big Two” Growth of Monopoly in the Meat Packing Industry. proletarian revolution. The two years had searcely begun to pass before strenuous efforts were made to have the decree modified, packers bringing pressure to bear from many sources. This move was led by the California Co-operative Canneries, whose contract with Arm- our and company was to have been cancelled as the result of the decree’s admonition that no packer engage in the distribution of products unrelated to his industry. Wholesale Grocers Protest. The California case brot an inter- esting turn of events. Two wholesale grocers’ associations,—the Southern and the National, filed petitions in which they took a positive stand against modification of the “consent” decree to permit packers to continue their operations in the wholesale groc- ery business and thus subject grocers to unfair packer competition because of the financial power of the packers and their superior advantages in transportation. That the grocers were right in their contentions was borne out by the commission’s report, which had stated that the packers’ immense selling. organization “assures them almost certain supremacy in any line of food stuffs that they want to handle” and that, “at the present tate of expansion, within a few years the big packers would control the wholesale distribution of the nation’s food supply.” It seems to be a law of capitalist economics that it takes a trust to bust a trust. And, of course, the mightiest trust wins. So the allegedly budding wholesale grocers’ trust didn’t stand a chance when face to face with the “Big Five” in the court of appeals, This court declared, humorously enuf, on June 2, 1924, that “If... the wholesale grocers are using the decree against the packers to strengthen and build up a giant mo- nopoly in their own \—rious and vari- ed lines of business, there would seem to be demand for a serching in- quiry as to whether or not the court is being used as an agency to restrain “Nine Hundred Per Cent Dividend!” Nash Motor stock pays 900 per cent dividend! panies are doing well. The little automobile companies are being swallowed up. This is the period in which monopoly rules. The big automobile com- It is also the period of the etn tneesestnsssteeenennsenensaensesneentntiennenn i strengthen and build up another. Clearly it is not the policy of an an- titrust act to accomplish this re- sult.” (!) A year following the postpone- ment of the case, April, 1925, the court announced that the “packer consent” decree had been suspend- ed, and on May 9, that it had been wiped out. Here ends another chap- ter of a government’s fruitless, fu- tile and fraudulent efforts to “regu- late” monopolies. As a testimonial to the “benefits” of government investigations, the fol- lowing extract from the letter of the chairman of the federal trade com- mission considered by the United States president, Calvin Coolidge, in February, 1925, is illuminating: From “Big Five” to “Big Two.” “Probably the most significant change that has occyrred recently in the relative sizes of the different packer groups has been brot about thru the purchase of the business of Morris and company by Armour and company. By this acquisition Armour and company increased its proportion of the total inspected slaughter of all animals from 17.4 per cent in 1923 to 23.5 per cent in 1924, which practical ly equals the Swift and company pro- portion last year of 24.2. “The combined slaughter of Armour and company and Swift and company for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1924, was 47.7 of the total slaughter of all animals and 78.7 per cent of the group formerly known as the ‘Big Five.’ The other surviving members of this group, Wilson and company (inc.) and the Cudahy Packing com- pany, last year slaughtered 12.9 per- cent of the total inspected slaughter and only 21.3 per cent. of the ‘Big Five’ proportion of the total, “These differences in the two big packer groups make it apparent that there is no longer a ‘Big Five’ or, strictly speaking, even a ‘Big Four.’ With Armour and company and Swift and company today slaughtering prac- tically 48 per cent of the total kill it is more proper to refer to them as one monopoly and thereby promote, the ‘Big Two,’”