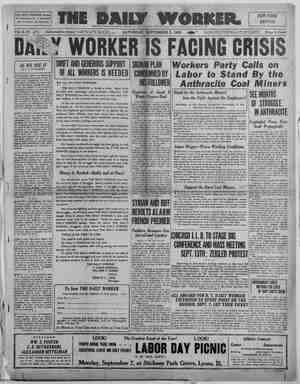

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 5, 1925, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

ae RS RR ET SR ET OT A Aste er LE EN EE SE Bryan’s Place in History - NOTE:—This article was submit- ted shortly after the death of Wm. Jennings Bryan, but it has been held up due to the great amount of material that had to be published in connection with the party discus- sion and the fourth annual conven- tion of the party. Since this ques- tion continues to be of great inter- est, however, the article has lost none of its value. eee HE death, at Dayton, Tenn. of William Jennings Bryan, removes from the American political arena the foremost champion of the petty bour- geoisie of this generation. The dom- inant note of the press comments up- on his career is that politically he was a “champion of lost causes,” a senti- mentalist, an anti-imperialist and paci- fist. Most writers express surprise that one can be so consistently a de- fender of principles doomed to failure as was Bryan. Denying the Marxian ‘concept that prominent politicians are merely the spokesmen of economic classes the capitalist publicists are at a loss to explain the career of this “prince of peace” from Nebraska’s shimmering plains. Champion for Bourgeoisie. Applying the Marxian interpretation of history to Bryan we perceive that his vagaries were those of the middle class of this nation. In politics he was the champion of the petty bouregoisie; in the sphere of religion he was their prophet. His career, from July 10, 1896, when with his famous “crown of thorns and cross of gold” speech he flamed like a meteor across the poli- tical horizon, capturing the democratic party nomination for the presidency of the United States, until his forlorn fiasco as defender of religious funda- mentalism in the famous Dayton trial, parallels the decline of the petty bour- geoisie as a political factor before the rise to supremacy of the powerful combinations of finance and industrial capital. R nearly two decades Bryan was the undisputed leader of the dem- ocratic party and for a third decade he had sufficient prestige to defeat any aspirant for the presidential nom- ination who incurred his enmity. These thirty years constitute an epoch in American political history. Economie forces operating since the panic of 1873 prepared the soil for Bryanism. That crisis marked the be- ginning of the development of trusts. In that panic thousands of small in- dustrialists and merchants were forced out of business. Those who survived grew more powerful and in given lines of industry combinations proceeded rapidly. These combina- tions were called trusts. The warfare of the trusts against the small capital- ists raged with such intensity that in the latter eighties and early nineties a wave of anti-trust agitation swept the nation. Most states passed laws against these combinations. The state of New Jersey, however, was ab- solutely dominated by “the interests” of that day and passed a special law granting free reign to the trusts: With this state as a base of opreations the trusts grew unhampered. Currency Reform Fallacy. A middle class political movement arose during this period, known as the populist movement. A third poll- tical party grew out of this agitation that had as one of its main planks currency reform. Many small caliber politicians of that day supported the demands of the populist party while remaining in the old parties, Bryan was one of these. In 1880, when thirty years of age he was elected to con- gress from the first Nebraska district, formerly a republican stronghold. He first definitely formulated the political slogan that made him famous in a speech delivered in the house of con- gress on August 16, 1893, when he opposed the repeal of the silver pur- chase clause of the Sherman act, and advocated “free and unlimited coin- age of silver, irrespective of interna- tional agreement, at the ratio of 16 to bed Currency reform had long been a favorite illusion of opposition move- ments in this country, starting with the greenback movement after the civil war. The advocacy of bi-metal- lism was an economic monstrosity, which in that particular case demand- ed the coinage of silver at the ratio of 16 silver dollars to every dollar in gold. As every Marxist knows it is impossible to jarbitrarily set a prieé upon silver and gold, for the simple reason that they do not exist in this ratio and the conditions of production constantly change in relation to both silver and gold. This economic ab- surdity, though, captured-_the minds of millions of voters in thts country thru two presidential campaigns. That Famous Speech, — At the democratic convention of 1896 in Chicago, at the close of a long debate on the question of bi- metallism, Bryan, having been de~ feated for re-election to congress and having suffered defeat as candidate _ for United States senator from his state, arose and aroused an exhausted convention to the wildest enthusiasm with his speech in defense of money reform. He concluded with the words “You must not place a crown of thorns upon the brow of labor; you shall not crucify labor upon a cross of gold.” His first nomination for the presidency followed this speech. Having stolen the thunder of the populists who had built up a strong movement on the issue of currency re- form by convincing the middle class that all their ills could be remedied if only the money moloch were crushed, the democratic party, thru the medi- um of Bryan, was able to swallow the populist party. Trust Busting Gets Votes. The working class of the United States was almost wholly unconscious of its separate class ffiterests and threw its support to this middle class movement. During this period of the rise of the mighty trusts many a self- seeking demagogue in the political arena secured a position of power and affluence by attacking these combin- ations and the working class was de- luded into believing that the road to its salvation lay in supporting the rapidly vanishing small capitalists against the trusts. In the ranks of the working class there was at that time but» a very small group of stu- dents of history and economics that pointed to the fact that “trust bust- ing” was an attempt to confine the highly developed capitalism of this country to the shell from which it emerged. Bryan, in the 1896 campaign, polled a popular vote of 6,502,925 to 7,104,799, for his republican opponent, William McKinley. Under the McKinley administration the government was the tpol of the big industrial capitalists. In 1898 the government provoked the war against Spain in the interest of the Have- meyer sugar trust and the American Tobacco company. Bryan opposed this war, altho he entered the volun- teer army, attaining the rank of colonel. At the close of the war he opposed the retention of the Philip pine Islands. Again, in 1900, he was the demo- cratic nominee for president, opposing President McKinley, the flunkey of the trusts. The outstanding plank was still “free silver,” but he waged his campaign on the slogan of “anti-im- perialism.” , The campaign of 1900 was obviously a clear-cut petty bouregoisie campaign. The theme of Bryan's speeches Pe ee By H. M. WICKS. against the republican policy was that a continuation of McKinley in power would increase still further the bur- den of taxation already too heavy for the small capitalist and farm owners. This time he was again defeated, poll- ing 6,358,133 to McKinley’s 7,207,923. “Commoner” Why? Dubbed “the commoner” because of his alleged defense of the common man,, Bryan still remained after these defeats the foremost champion of the middle class. After his second defeat he started the paper, The Commoner, in Lincoln, Nebraska, where he con- tinued to assail imperialism and the goid standard and began to advocate government ownership of railroads so that the farmer could market his pro- duce without paying tribute to the railway magnates and the small busi- ness Man could escape the excessive freight charges. Economically this period was char- acterized by the colossal growth of trusts. During the single year, 1897, there were incorporated under the laws of the state of New Jersey 4,495 companies with a capital of $1,400,000,- 000. Practically all these companies were trusts, having as their object monopolies of products of a certain industry or control of public utilities. By 1904 the merciless inroads of the trusts were ravaging tne middle class to such an extent that no politician dared defend them. A Rival Trust Buster. McKinley was removed from the scene by an assassin’s bullet and the demagogic Roosevelt succeeded him as president. His forte from the first was trust busting; a direct bid for the support of the petty bourgeoisie, while remaining the political head of the republican party of industrial cap- italism. Unable to prevent the renom- ination: of the spectacular “Teddy,” Wall Street endeavored to get control of the middie class democratic party and use it for its own purposes. At the 1904 convention Bryan resisted with all his power. the efforts of Wall | Street to name the standard bearer of the party that he had come to re- gard as his own. His efforts were un- availing and Judge Alton B. Parker was elected to run against Roosevelt and was overwhelmingly defeated. After a trip thru Europe Bryan came back and began a strenuous campaign for world disarmament and intensified his advocacy of government ownership of railroads. . ri At the democratic convention of 1908 Bryan routed the agents of the House of Morgan who tried to control (Continued on page 7) Juniors at the Leninist Camp of the New York League, © eR SS,