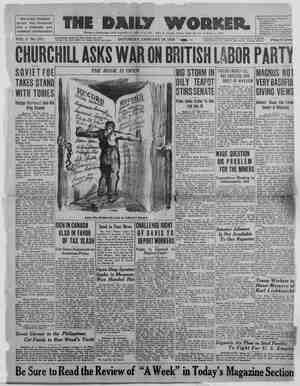

The Daily Worker Newspaper, January 19, 1924, Page 11

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

HER LOVE An old acquaintance of mine once told me the following story. When I was a student in Moscow I happened to live alongside one of those excellent ladies whose reputa- tion is of rather a transitory kind. She was a Pole and they called her Heresa. She was a tallish, power- fully-built woman, a brunette with black, bushy eyebrows and a large coarse face, the sort of face one would imagine to have been carved out with a hatchet—the bestial gleam of her wicked eyes, her cabman-like walk and the whole immense mus- cular vigour of her filled me with horror and loathing. At that time I lived on the top flight and her garret was directly opposite mine. Never on any occasion would I leave my door open if I knew that she was at home. But this, after all, was only on very rare occasions, for she seemed to spend all her time in cafes and other places of the sort. Some- times I chanced to meet her on the stairease or in the yard, and then she would smile at me with a sort of leer that seemed to be cruel, sly and cynical. Occasionally I saw her drunk, with great bleary cyes, tousled hair and a particularly hid- eous grin. On such occasions she would speak to me. “How d’you do, Mr. Student?” and her stupid laugh would further ac- centuate my intense dislike of her. I should have liked to change my my quarters in order to avoid such encounters and greetings, but many ways my little chamber was a nice one; there was such a charming view from the window and the street beneath was always quiet and orderly —so I stayed on in spite of her. One morning as [I lay lazily enough on my couch, trying to imagine some excuse for not attending my Class, the door opened and the loud voice of Teresa the terrible came to my ears. “Good health to you, Mr. Student.” “What do you want now?” I said. I saw that her face was confused and supplicatory. ...A very unusual sort of face for her, certainly. “Sir, I want to beg a favor of you, yes, indeed I do. Will you ant it?” : e lay quite silent and thought to myself: ~ “Good heavens ... Come now, courage my lad. What can she want of me?” “I want to send a letter home.... That’s what it is,” she said, her voice becoming beseeching and timid, like the voice of a frightened child al- most. “Deuce take you,” thought I, but I jumped up, sat down at the table, and, taking up a sheet of paper, said: “Come here. tate.” She came towards the table, sat down rather gingerly and looked at me with a guilty look, “Well, to whom do you want to write?” “To Boleslav Kashput, at the vil- lage of Svyeptsyana; on the Warsaw Road.” “Well, fire away!” “My dear Boles . -. . .. My faithful lover, May the Mother of God protect thee! Thou heart of gold, why hast thou not written for so many weeks to thy sorrowing little dove Teresa?” Thad great difficulty to keep from Jaughing. “A Sorrowing little dove!’ More than five feet six inches tall, with fists like-a boxer’s, and as black a face as if the dear little dove had passed all its life in some coal-house without ever washing! mvself. somewhat. I asked: “Who is this Bolest?” “Boles, Mr. Student,” she said, with an almost offended air, as if she resented my having mispronounced the name. ‘He is Boles, my lover— my young man, “Voung man?’ “Why, yes. young man’ then? girl after all, eh?” “She. A young girl. Oh dear, oh dear,” “Oh, why not indeed?” IT said. “Well. let us write your letter!” And I tell you very candidly that I would willingly have changed places with Boles it only his mistress had been someone other than Teresa. When I had at last finished. she Sit down an& dic- My darling May not I have a Surely I am a said to me with a most polite curtsey: | “T thank you most heartily for your kindness, sir. Is there, then, nothing I can do to requite you for Restraining | F the great trouble you have taken in writing this letter for me? Your shirts or your trousers may need mending, perhaps, eh?” “No, I most humbly thank you all the same.” I felt for the moment that she had made me go quite red with shame, and yet I knew of no cause for the feeling of such shame before her. Then she went away, slowly as if she would have wished to stay longer with me. Thank God, she did not, however. A week or two passed and I saw hardly anything of her. One veve- ning, rather late, I was sitting at my window and whistling to try and drive away some of the terrible monotony. F was horribly bored. The weather was vile and I felt my- self entirely at a loose end for some- thing to do. From sheer tiredness of life I began a desultory sort of self- analysis. God knows this was dull enough work, and I was about to abandon it when suddenly the door opened. God be thanked. Someone entered the room. “Oh, Mr. Student, you have no very pressing business, I trust!” It was Teresa. Humph. “No, what is it?” “I was going to ask you to write me another letter!” “Very well. To Boles, eh?” “No—this time it is from him.” “What?” “Stupid girl that I am—it is not for me, Mr. Student, I beg your par- don. It’s for a friend of mine— that is to say, not exactly a friend but more an acquaintance, perhaps —@ man acquaintance. He was a sweetheart just like me here, Tereso. That’s how it is you see. Will you be good enough to write me a letter to this Teresa?” I looked at her. She was obviously troubled. Her fingers trembled. For a moment it all seemed very foolish and hidden to me, then suddenly I saw how things stood. “Look here, my lady,” I said. “There is no Boles at all and neither is there any Teresa. You've been telling me a pack of sheer lies, and that’s all there is about it. Now, I don’t want your company at all, I assure you, and you had better let the matter drop now, once and for all.”’ ‘Sudden.y she seemed to grow very terrified and distraught. She began to balance herself on one foot and then upon the other. Her face was suffused with a violent blush and she begah to splutter in a comical man- ner. I instantly saw that I had made a great mistake in imagining that she wished to draw me from the path of virtue. No, it was evidently some- thing very’ different. “Mr. Student,” she began, then suddenly she turned and, with a wave of her hand, left the room. For ‘\ am Wn on! Ui u\ ue ae | * {| fem (1A Pa I TT ‘ Sia cal Tr a few minutes I sat there with a de- cidedly unpleasant feeling in my mind. | listened. Her door was flung violently to—plainly the poor wretch was very angry...... thought it over and at last decided to go-to her, and, inviting her to come into my room, to write what- ever on earth she might fancy. I entered her room and looked eround. She was sitting at the table, leaning her head on her hands and down her face ran two great tears. “Listen to me,” I said. Now, whenever I come to this part of my story, I always feel most jidiotic and childish, Heaven knows why, but it is so. “Listen to me.’ She seemed to leap from her seat, such was her haste, and, coming to me, she placed her two hands on my shoulders. Then she began to whisper in a pecuriarly low voice. “Look now. It’s like this. There’s no Teresa. But what in the name [ne Boles at all and of course there’s ; of God is that to you. Is it then such ls hard thing for you to draw your pen across a sheet of paper for my pleasure? Eh? Answer me that! Still such a fair-haired little boy, my God I almost love you as if you were my own son. No, there’s nobody at all; no Boles, no Teresa; there you have it, and much good may it do you also.” “Pardon me,” I said, utterly dumb- founded by such a reception. “What does all this mean? There’s no Boles, you cay. No Teresa. Come, tell me all about it like a good little girl. Come now.” “No then—so it is, Exactly like that.” I didn’t undersjand it at ‘all. I fixed my eyes upon her “and tried to make out which of us was losing his or her senses. But she went slowly to the table, searched for something, and then returned to me, saying in an offened tone: “Tf it is so terribly hard for you to write to Boles, there’s your letter. Take it. Doubtless others will write to him for me.” - I looked. In her hand was the let- ter I had already written to the non- existent Boles. “Hum,” thought I, “this is getting more complicates every moment.” “Listen, Teresa. What is the meaning of all this? Why must you get others to write for you when I have already done so, and yet you haven’t sent it?” “Sent it to where?” “Why to this—Boles!” “There’s no such person.” Absolutely and utterly I failed to understand her or it. There seemed nothing for me but to split and go, as they say in little Russia, Then, with an effort it seemed, she ex- plained. SS essen Translated from the Russian by J. SUTTON- PATERSON — ~ “What is it?” she said. “As I told you, there’s no such person on earth. 'Boles never existed for a minute even. I wanted him to exist so terri- bly, you see. Am I not then a hu- man person like you and other peo- ple?) What harm was there in my writing to him even if he never re- ceived the letters. No, surely I did harm to nobody at all by this silly trick of mine.” I said nothing; as far as I could see, there was nothing to say. “When you have written a lettter to me from him, I take it to my girl |friends who read and are jealous. ; They all wish they had a lover like me. Some of them even have the courage to tell me so.” At last I understood and felt hor- ribly ashamed of my stupidity. By the side of me, not three yards away, fwas a poor human creature for whom no one in all the world had the least love or sympathy. This poor creature had been forced to invent a friend for herself. A good and true friend thgt never existed, or ever could. | .va see,” she continued, ,“when they read these letters to me it seems as if he almost existed and really loved me a little. It makes life so much easier for me in every way. “Deuce take me for a fool,” said I, when I heard this. And from thence onward, twice a week, I wrote her a letter from Boles, and an answer from Teresa to Boles. I wrote these letters well, I can assure you, and she listened to them and wept—wept? Roared, I should say, for her great bass voice filled my little room entirely. That was really the last I saw of her. She left the house some little time after- wards and vanished entirely. I heard that she had stolen something or other and been put in prison for it. Heaven alone knows. My acquaintance shook the ash from his cigarette, looked up at the sky pensively, and thus concluded: “Well, well, the more a human creature has tasted of the bitter things of life the more he hungers for the sweet ones. And we, wrapped round in the rags of our virtues, and regarding others through the hellish mist of our self-sufficiency, and firmly persuaded of our own impre- ciability, do not well understand such things.” And the whole thing turns out stupidly enough—yes, stupidly and very cruelly into the bargain. The fallen classes we say. And who are the fallen classes, I should like to know? First of all, they are people with the same bones, flesh and blood as ourselves; We have been told this day after day for ages and ages. Yes, they tell us things like this and we actually listen, yes, listen, and the Devil himself only knows how horrible and cruel the whole thing is. Or are we completely depraved by the loud sermonising of humanism? In reality we are all fallen folk. and, as far as I can see, very deeply fallen into the abyss of self-sufficiency and the terrible conviction of our own superiority. But enough of this. It is all as old as the hills—so old that really it is a shame to speak of it, or even think of it perhaps. ‘ Yes—very old, indeed. That’s where it is. The Sifter Odd little figure, God! Working in an earnest ewelter,— Shaking thru his skyey sieve All that doés and does not live; All that falls in helter-skelter Tumult to®the earth... .. He is sober in his sifting, Not a flare of sunny mirth. Down the woeful ash comes drifting, All the -things we think of worth, King and sinner, crook and savior, Drifting, sifting, sifting, drifting, Like a horrid filth of ashes Spread upon the earth. Shrewd little worker, God! All the rest—the things that are Fit to shine on a young star—~— Stay within the cautious sieve. They're not wasted on this planet. They are saved to build some far World, where life may live! —CLEMENT WOOD.