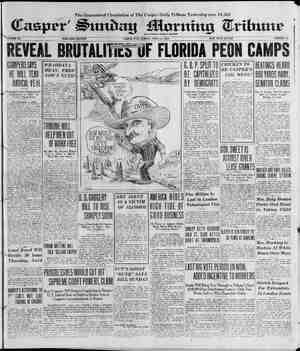

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, April 15, 1923, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

’ SUNDAY, APRIL 15, 1923. “SOULS FOR SALE’---A Great Novel of Hollywood Li BY RUPERT HUGHES a structure. He groaned at the -omic] will seno it for me. — CHAPTER XLVIIT (Continued) Ii.tter philosophy it was ans shock- to the best principles, yet it was ash of the pride that rewards con- escension and patronage and mawk- ish charity with a kick in the tall and takes to flight. It pictured what everyone in the audience had often wanted to do in those resentful moods Which are so very human be- cause they are so far from divine. Yor the soul, like the body, needs its redemption from too much sweet- ness as well as from too much bit- terness. There is a diabetes from un- ossimilated sugar that is as fatal as too much salt. And that is the noble service that farce and clownery render to the worlé, They guarantee the freedom of the soul, freedom not only from glooms and despairs, but from the tyrannies of bigotry as well, from the outrages of religion, of grovel- ing idotatries, all sorts of good im- pulses and high principles that ought to be respected but not revered, ought to be used in moderation but not with slavish awe, Going to a farce of such a sort was, for Remember Steddon, going to a school of the highest educational value; It was a lessoning in life that she sorely necded. She had been taking life and love and art and ambition and sin mo- rosely. Tom Holby found her already changed when they set out for her home. She had been restlessly un- approachable before the comedy, like a mustang that will not submit to the bridle, will not run far but will not be taken; that stands and waits with a kindly alr, but, just as the hand reaches out, whirls and bolts. Now that she had seen the picture she was serene. She was genial, am!- able. She snuggled close to Holby in the car, and yet when he spoke ten- terly she made fun of him, giggled. reminded him of bits of the picture that had amused her. This enraged him. “Um going in for comedy,” she raid. “It's the only thing worth while All this tears and passion business makes me sick. I'd love to have it so that when anybody hears my name he smiles, Wouldn't it be glorious to have a washerwoman look up from her tub and say: Remember Sted- don? Och, yis, I seen her in a picture once and I laughed till I cried’? ‘Wouldn't it be glorious to have the tired business man gay to his tired society wife: ‘I've got the blues, and ‘io have you. There's ene of Steddon’s pictures {n town. For God's sake let's go see it‘and have a good laugh” Weuldn't that be a wonderful thing to stand for Holby made a grunting sound that implied, “I suppose so, if you think so." He added, after a silence: “Fun: ny thing though; more people get relief from a good cry than from good Inugh. If you have teara to shed, and you go laugh your head off at some damfoolishness, you'll find the tears are still there when you get home. But if you see Camille or Juliet or some-pathetic thing, if you watch some imaginary person's mis- ery and cry over it, you'll find your own tears are gone. “That may be true,” said Men, “but acl the same I'd lke to take a whack at comedy.” Holby fought out in his soul a de- cent battle of self-sacrifice before he brought himself to the height of ro- commending a rival. “There's Ned Ling; he's looking for a pretty lead- ing women. He's not Chaplin, but he's awfully funny in his own way and he's getting a big following. He usually gets engaged to his leading lady—saves money that way; they say. If you're so hell bent on a com- jc career get your agent to go after ed Ling,” she mused. “Yes I've seen him. He's fun. He might do. I may make a try at him a little late>. Just now I feel all tukered out. I want to get away from the studios, out into the Sterras, I believe I'll buy a little car and go all by my- self." But when she reached her home there was something waiting in am: push for her—a letter from . her father. And this was not farce, nor to be greeted with a kick and a run. “Oh, I was wondering if it would ever come!” her mother wailed as Mem came laughing in the door, still Jaughing at Chaplin's blithe rebuff to maudlin penances. It was odd to be greeted so by the patient little woman who irrl- tated Mem oftenest by her meek pa- uence. “T was worried for fear you had some accident. Why couldn't you ve telephoned me?” Tf tala you I might be detained at the studio, mamma, and not to ex: pect me till you saw me,” Mem ans- wered, and had not the courage tell the rest of the truth. “Oh, I know! I oughtn't to ‘a’ wor- ried, but I'm a nuisance to my self and to you and to everybody.” There she was again! Taking that maddening tone of self-reproach. But Mem simply could not rebuke her for it. She embraced her and held hor . instead. sent aaa all because of a letter I had from your father, If you had come home sooner I wouldn't have mentioned it to you, maybe! Heaven knowns you have trouble enough, and now I'm sorry I spoke. Just it.” tren ensued a long battle over the letter, Mem insisting upon reading it, fighting for it as for a cup of poison held out of her reach « And it proved to be a cup of poison when finally she ee {t from her mother’s reluctant fingers. DEAR WIFE,—The Lord giv- eth and the Lord taketh away. I have lost you and my darling daugter and my head ts bowed In shame and loneliness, but 1 still can say, “Thy will be done.’ I think you should know, how- ever; how things aro here. Other wise I should not write you. But I am afraid that the daughter that was once ours might tire of husks of sin and wish to come e repentant. Voie filled my eoul when T learned that she was leading a life of riotous mockery, and when T naw the picture of her smiling in wanton attire at the side of that smirking French general, I had | | | to} in my heart to curse her. I wrote in my haste. I repented my hardness of heart and bowed my head in humble shame when I read your angry reply. I had lost your love and your admiration, but that was deserved punish- ment for the idolatry that had grown up in my heart toward you; and for the mistakes I must have made in not giving our erring daughter a better care, But now it has pleased the Lord to pour out the vials of his Wrath on my gray hairs. The old mortgage on the church fell due long ago but foreclosure had been Postponed from time to time. ‘We gave a benefit to pay it off, but everybody was too poor to respond, and it did not pay ex- penses. The manager of the motion-pic- ture house here offered to share the profits on the showing of a Picture in which, as he had the impudence to tell me, my daugh- ter played a part. But while it would have drawn money for cur- fosity that would not have res- ponded to a christian appeal, I felt that it would be a compound. ing with evil, and I put Satan be- hind me and ordered the fellow out of the house, ‘Then I made a desperate appeal to our banker, Mr. Seipp, and he promised to do what he could for us. But the other day his bank was closed after a run upon it. He had previously mortgaged his house and sold his automo: bile—the one that killed the poor boy, Elwood Farnaby, whom you will remember as one of our cholr. ‘The banker was the only wealthy member and with him failed our last hope. The crops have been Poor and the hard times have af- fected the local merchants so that Pew rents have not been paid-and the usal donations have been withheld. There were no conversions at the last communion. Even the baptisms and the weddings that brought me an. occasional little fee have been wanting. ° The campaign we made to close the motion-picture houses on Sunday was lost at the last ciec- tlon. We are fall on evil days. What small religious enthus- + jasm ts left in the town has been @rawn away to other churches where there are younger ministers with more fashinable creeds and fresher oratory. I have not been spared, overhearing carclessly cruel remarks that I was too old to hold the pulpit any longer and should give way to a fresher mind; but I have not known where else to go, as I have had no calis from outside. And I could not—God forgive my vanity —I could not believe that I was. yet too old to toll in the vineyard of the Lord. I have — endured every other loss but that, and new the vineyard ts closed. ‘The curch is to be closed. We * had no fire in the stove last Sun- day and almost no worshipers were present. The sexton was il and his graceless son refused to leaye his bed. ‘What I shall do next or haw take care of the little children that still cling to our home, the Lord has not yet told me in ans- wer to my prayers. I still have faith that in his good time he will provide a way or call his ser- vant home, and I hope you will not take this letter as a plea for pity. It is only to explain to you that if you should plan a return to the fold you will find the fold a ruin. I could not even send you the money for your rallroad fare. There was a piece in the paper saying that the moving-picture studios were also closing for lack of funds, and ? wonder if my poor daughter has been turned out of the City of Pleasure in which she elected to spend her life. The rain falleth alike on the just and the unjust. My cup fs full and running over, but my chief dread is that unhappiness and want may be Your portion as well as mine, and that I shall fail you utterly after providing so scantily for you all your days. I can only pray that my fears are the result of lone- liness and age and weariness, It has not been easy to write this, but it would have been dis- honest not to le® you know. For months I used to think, every time I heard the train whistle; Perhaps it brings my loved ones home. For the last weeks I hi feared that {t might, lest I should have to welcome you to utter pov- erty. Even the oil is wanting to keep burning the lamp I used to set in the window every evening. And now may the Lord shield you with his ever-present mercy, or at least give us the strength to understand that in all things he knoweth best. Your loving HUSBAND. had no time to shop or even to go down Into the streets and stare in in the Sunday sup What car to buy and what new house to rent had been amusing con- | undrums for idle moments of musing And now those conundrums were solved. Her mother sobbed: | “What on earth can I write the | Poor darling?” |_ Mem replied: “The answer is easy. I'm going ty send him all the money I've got.” Her mother cried out against rob- bing one of her loves to pay another It seemed a cruel shame to take the first bit of cake from her daughter and sell it to buy bread for her hus: band. “You'll need it yourself. not have another job soon. new clothes and a rest,” “Rest and the clothes can wait.” Her mother kept a miserable si- lence for a long while before she could say: “Your father will never accept money that you have earned from the pictures. You know him. He'd rather die. He'd rather the whole world would die.” This gave Mem only a brief pause She answered simply: “Doctor Breth. erick got me into this business by making up the pack of lies that brought me out here. Now he can make up a few more and save poor | daddy from desperation.” She sat down at once and wrote the doctor a letter tel!ing him what he must know already of her father's helplessness. She inclosed a money order for two bundred and fifty Col Jara She wrote a chicck first, bu tshe was afraid to have ‘t put through the bank at Calverly lest her father hear of it. She instructed the doctor to make up another of his scenarioe about a repentant member of the con gregation wishing to resore some You may You need {stolen funds—or anything that his imagination could invent. ‘Then she set the wheels in motion |to secure an immediate engagemen with the next to the greatest come dan on the sercen, Ned Ling, a man whose private life was as solemn as his public life was frantic and foolish | whose personal dignity was as sacrec as his professional dignity was de graded; a man of intellectuality | reader of important books a debater of art theories—but above all a mar afraid of nothing so much as he wa: afra‘d of love. : ‘The Bermond company was declar- ing another holiday, letting out such of {ts people as were not under con tract, farming out such others as it could find places for in the shriveled market. | The public was not flocking to the pictures or to anything else. The exhibitors were losing money or clos ing down. It was a period of dead calm and torpid seas. Wise men were trim- ming sails to the least broeze and Jettisoning perilous cargo. The too courageous one were sinking, van'sh jing, blowing up, dying of famine. j. When Mem spoke to Bermond of | has always been a wondrous sedat! her desire to play a comedy with Ned Ling, Bermond leaped at the idea. It would take her off his salary list for weeks and it would help her fame. He Was not altogether selfish, He arrang- ed a dinner under the pretext of a private preview of Tom Holby's new picture. It was not yet in its final shape, but the producers were gind to lend it to Bermond. Bermond warned Mem to wear her best clothes. There was certain shame in her heart at baiting such a trap, but she felt now that she had a higher pur pose than her personal ambition. She was working for her father and his church as well; and religious motive to a conscience. Bermond saved her the price of a | own by lending her a flashing Par inian miracle from his own wardrobe It was astounding to him as it was to Mem to find what a change clothe: made in a soul, The simple things she had worn hitherto had once giver her a simple modesty. In her first scenes sho had been as bad es Miss Bevan, Zorever pulling her skirt down. Her muscles rensembered) when her mind forgot. Kendrick had yelle: to her once, “In God's name, Mis: Steddon, forget your knees and don't advertise them by always covering them.” ‘When she saw herself before her mirror now in the Paris gown shoe re cotled in red horror, A tide of: blood swept under her entire skin. bosom was bared in a great moon: sweep, there were no straps at al across the shoulders, and her back was revealed to the waist, She had never known how beautiful it was until she stood before her mirror and looked slantwise across her shoulder at the creamy charm of the gently rippling plane. She rose to the challenge of oppor- tunity and clothed herself in audacity. The consciousness of her beauty gave @ lilt of bravado to her carriage. As. she read this letter and saw/| She was happy in herself and silenced back of the lines the heavy brows of; her old modesties with a pious her old father, saw the bald spot she had stared at from the choir lot saw all tho sweet wrong-headednet of the veteran saint, Mem’s heart hurt intolerably. From her eyes fell streams of those tears that she had sold for so much apiece. Her face was blubbering and crumpled and soppy as in the crying contest for points. * The old-fashioned heartache and eye shower ended in an old-fashioned hysterics of shrieking laughter, of farcical cynicism at the ridiculous subiimities of life, She startled her mother by crying suddenly: ‘The Lord {s another Charlie Chaplin mam- ma! He just planted another kick whero {t will do the most harm. CHAPTER XLIX Mem had been debating what make of car to buy. Care were cheaper in price now, and wonderful bargaine were to be had in slightly used cars purchased by hardly used stare who could not complete the payments or keep the gasoline tank filled. Bhe had cried herself into money —not much, but a good deal con: sidering the hard times, the general unemployment, and her inexperience. Bhe had spend little of it, thought that the Lord never gave her such flesh for concealment. Her mother was pale with terror of the white swan this pretty duckling had grown to, but she let her sall away. ‘The unsuspecting Ned Ling came to the dinner and never dreamed that Mem was there to play the Lorelel, She shuddered at her own coquetry, but it was for art's sake and Heaven's name besides. She met the comedian with a mixed attitude of homage and of self-con- fidence. Sho made him proud and she made him happy, Best of all, she put him at his best, He said witt: things and her laughter as a final allurement. 5 After the dinner they sank into big chairs in the Bermonds’ living room to watch the new picture. From @ table behind them a little domestic projection machcine sent a cone of Mght across their heads to a small curtain. And there a Lilliputiar twin of Mem wept and fought and won through a tiny drama. From the dark, the happy gloam Ned Ling kept erying out his enthu- | slasme for Mem's skill. Ho was frank Casper Sunday gBorning Cribune relief and he shouted tn ridicule of the ackneyed situations. Bermond ¢:ho- ed his praise and his censure, The picture was not a Bermond creation but Mem was. In an interlude during a change of reels Ned Ling sald, with all the exrn- estness of an earnest clown: “I love your ears. Miss Steddon! they make ine weep. See how wet my eyes are'” He leaned close and made her look Into his melancholy orbs. Their moelencholy Was thelr fortune, for in his pictures he never smiled except when he was in a plight of comic despair. love to weep” ho went on, shamelessly. “Last Christnias—How do you suppose I spent my Jast Christ: yas? I stayed at home alone and felt sorry for myself. I did’ Honestly! I just wallowed in self-pity. I sat for an hour before a mirror and watched the tears pour down my cheeks. And when they fell into my sobbing mouth I dronk them, and loved them be- couse they were so bittcr It was the happiest Chra:tmas I ever spent. Next Chrictmas let's you cad me sit to- gether before a mirror 1! have a glorluus ery and weeping due; can't imagine snyone who f make me weep as lusciously as you. Will you come I'll be there” said Mem, half with cnd half with mockery pit Therupon, as ths Nghts went out again. he latd his hand on hers wher, her chair. it it rested on the arm of When she moved it he clutchet eagerly and whispered, “Oh please’ and clung to {t like a lonely child. He laughe¢ aloud at tne wonderful vatue Tom Hulby put up, but he cheered Mem's every scene as she lashed through the storm How brave! How beautiful you are! he murmured. leaning close. She whispered to him the tale of how near she was to death in the scene when she trust her way through the tree. And now he clung to her with both hands as if he would save her thus belatedly from danger. “I was very/near to death in my pictures” she said. “I was supposed to sit down innocently on a plumber's torch. I had on asbestos trousers, but some how my cont tails caught fire and I should have burnec to leath {f Miss Clave hadn't thrown \ rug around me. Awfully nice girl. I could have gone on loving her, but she kept talking marriage and I was afraid of marriage. Aren't you? It sickened me when I heard the audi- nee scream with laughter at the scene. We kept it in as it was and gave it a funny title. It had just the touch of obscenity that every body loves. Too bad we Americans make such a bane of obscenity! A little wholesime smut never hurt any- body. When the picture was finished he tald Bermond what a genius he had n Miss Steédon and said he wished he had her himself. Bermond adrott- ly and coquettishly forced the card on his hand, and before Ned Ling quite knew it it had been arranged that Mem should be lent to him at a figure far above Bermond salary. “[ stuck him for the extra money.” Bermond laughed after- wards, “but I tove to make Ned Ling pay. It hurts him so. I'll split the bonus with you, my dear.” CHAPTER L ‘Tom Hdlby called on Mem the fol- lowing evening. He had so earnest a face, eo longing a manner, that she had not the heart to tell him at once of her triumph over Ne@ Ling and her engagement to play the leading role in his next farce. But Holby seemed to realize that something had happened to take her 2 little farther out of his parish, There was a sagaciousness in her manner, and independence of h'm, that terrified him. He grew as flat-footed!y direct and simple as one of the big, bluff he-men he so often played, He act- ually twirled h’s hat, running his fingers round and round the brim as he did when he was a cowboy making love to a gal from down East He was as sheepish ag Will Rogers playing Romeo, but not so shriek- ingly funny. His very boorishness pleaded for him, and if Mem had beon free ct this new hunger of hers for a taste of comedy she might have taken pity on him lovingly. But she was in a mood of defer ment at Ieast, and she smiling, teas ing manner baffled him. In his con fusion ho noted a bundle of letters in his pocket, and for lack of other tonlo pulled them out. “This is a pack of letters that came to the studio just as I was leaving he explained, “I stuffed ‘em in my pocket, Haven't had a chance to look them over, Mostly mash notes, T guces.” He took out the lot and riffled them over like a pack of cards. “If they think wes movie people ere fools, what have they got to say of the public doluges us with this stuff? Here's one. Let's seo what it's Me He read from « welter of passionate script, “DEAR MR, HOLBY—I¢ I could only tell you how much I admire you you would be th Proudest man on earth, There's a pleture of you on my bureau now, but it's on'y e clipping from a Sunday supplement, I take it out only when the door is locked. Mamma would skin me if she Rnew I had it. I turn it away when I dress. but, oh, I do just admire you so much. If T could only have a real photo of y ou to kiss gocd night how proud I'd bo. ‘Won't you please send me one? ‘With your own really truly auto- graph on it? You are my favor- ite of all actors—so manty and virile and handsome. Oh, I just—" Tom shook his head and stuffed it back in its envelope, Will she set the photcgraph? Mem, with the scorn of one for another. “Oh yes. We can't afford suld woman to an- She enough to criticism of the picture as tagonize a single fan, My secretary under his eyelids. there was a tinge of jealousy in her heart. That would be vastly en- couraging, But contempt only, for men and the par- asitesses that haunt them. fully— valet, dresser and secretary. saw that they were boring Mem and woman you—you—" constable, so different from the path- a picture and autograph “Who is your secretary—a girl?” Holby slid a glance of eager query He hoped that her eyes revealed “No, he’s a man,” said Tom, dole- ‘combination of press agent, Tho next letter had a Philippine Islands postmark. It was from a man in Cuba. It said: “DEAR FRIEND,— please send me a copy of your sympathy portrait. Hoping to recelve it your benevolent reply Many thanks for my best wishe: Kindly He read a few moro. They repre- sented a cosmic cllentele.. But he Put them back into his pocket. “Brave man," she sald, “open your mail in the presence of the “IT love end expect to marry,” he said, gripping her hand. It was a stip of authority. It was Cupid the etic clutch of Ned Ling the clown chitd, Just now it was Mem’s humor to cuntrol somebody, She did not op- pose Holby's clutch or resent it. She followed the most loathsome and ex- asperating of all policies, nonresis- tance, “You're not going to marry me, Tommy,” she said. “I don’t want You're wedded already to an army of fans, Half the women in the United States seem to claim you as their spiritual triddgroom. | I'd @s soon marry a telephone booth or @ census report. You make Brig- ham Young look like a confirmed bachetor; he had only forty wives You have a million. or so. “They make me tired. be, but what wouldn't they So to me? I'd get poisoned candy or Infernal machines in the mail. 1'd never dare marry you. It would be cammitting suicide. She was not altogether without seriousness; she felt a primeval jeal- ously, a primeval sense of monopoly. She writhed at the thought of por sessing only a minute fraction of a artistic admiration, as the mediaeval untversal husband a syndicate con- sort whose portrait on a thousand bureaus inspired numberless strange giris and spinstres set up frnages of women with an ardor they called saints and made violent love to them under the name of religion, clothing what they interpreted as heavenly yearnings. Mem turned green at the thought of a husband whose real Ups she must share with actresses on the seene and whose pictured lips would be kissed guod night all around the world. Iq was a monstrous, fantastic Jealousy, but its foundation was real, She shuddered at the prospect of being embraced by a real hu: band whose virility thrilled a muttt- tude of anonymous maenads. If all these Idiots wrote, how many must there be who worshiped in silence? But she did not expres this revul- sion to Tom Halby, She did not real- ly feel enough Cesire for him just now to be jealous, except with a prophetic remoteness. Just now she was curious about another type of soul, about # comic sprite, She felt sure that no women wrote Ned Ling love letters or set him up as an icon-on a bureau. Ned Ling's pictures were not sifting around the xolbe, setting fool girts aglow, for Ned Ling's published portraits were always grotesque. He was photo: graphed with a caricutured face of white chalk and a charcoal grimace, with a nosensical hat and collar be- coming alomst as familiar now as Charlie Chaplin's neat slovenlines: end his mustaches, and his eplay- foot shoes, Surely Ned Ling was free from the amorous bombardment of anonymous love letters. A woman might stand a chance of keeping this heart for her very self, and it would be cheerful to have one’s own comecdan on the hearth. Thinking these things, Mem sald: “I'd be jealous of your public, Tom. It is a big one and you've got to be true to it, I suppose it's because I've got none of my own. I’ve hardly had a letter yet. “That's becau your first picture is only being released now. Just walt! You'll be snowed under.’ “And would you Mke it if I read you a letter from some man in Okla- homa who had my picture on his bureau and kissed mo every night good night?" “No.” “Would you be jealous?" “Yes! I'd want to kill him." “Really?* There was a pleasant thrill in this—e thrill that will bea long time dying out of the female soul, the excitement of stirring up battle ardor in two or more males. Mem went on, teasing, yet oxplor- Inty: ‘And would you kill any man who put me on a shrine and worship- ped me?” “No, I'd realize that that was part of the penalty of loving a great ar- tist. There's a penalty about loving o stupid woman that nobody else cares for, too, I'd realise that you have a right to the world's love, and I'd be proud of you, hawever much it hurt. I shouldn't lift my finger to hamper your glory.” She was just about to kiss him lightly on tho nearer ear for tho fer. vor of the first part of his speech. But the fast line checked her, There oan never fail to be a little soma- thing disappointing about a love that fs willing to share ite prey with any- cme elsexeven if it ts with everyone else, Perhaps to punish thie sickly saint- liness sho told him flatly now that she was going to be Ned Ling’s lead ing lady, ~ This"hurt him as much as she hoped. ‘It's come-down for you,” he sald. “It's a setback. You'd have been the next big star in the emo- tional field. Now you'll be swelling all up in a comico two-reeler. Ling never gives anybody else any credit in bis pictures. All you'll do will be to nd round and feed him.” “Feed him?" “Yes, do things amd say things that wil give him a funny comeback." This was a trifle dampening. If had held to that line of argument he might have turned her aside. But, as always he had to say too much. “Besides, as I told you, Ned Ling always makes tove to his leading lady. He qua®relea with tho last one, Miss Clave, because she wanted more publicity. She wanted to get a laugh or two herself and a lLne or two in the advertisements.” This stirred in Mem a double emo- tion—one of curiosity, one of self. confidence. She had had Ned Ling clinging to her fingers like a baby. She could wrap bim round one of them, no doubt. Because Miss Clave failed, that did not prove that a wiser woman would. Holby did not quite persuade her to refuse the opportunity with Ling, but he sent her to it misgivings. He put ® fly in the ointment. ‘There are always flies in ointment A few cays later a wasp fell into her ointment. She received one of the first of the numerous letters that wore to swarm about her path. CHAPTER LI. Time in southern California flew on wings that seemed never to change their plumage. At home in Calverly the birds put on their springtime splendor, lost {t, and flew away. Tho rees feathered out in leaves and in a courtship glory of blosscms, then lost all. The flow: bushes ran the same scale from shab- biness to brief beauty and back again. The very ground was brown. was green, was bald, wag white with snow that went and came again, But Los Angeles was always green In December, March—always there were great roses glowing, often high up in some tree they had climbed. Sometimes Mem grew angry at the monotony of beauty. She read of biizzards in the east and north and longed for a frostbite or the nipped cheeks of a Calverly winter. There was music in her memory of the frozen snow that rang lke muffled cymbals under her achinz little feet 8 she ran to school pretending she was a locomotive and her breath the steam. But this wns only the fretfulness of the unconquerabie human discon tent. She had thated winter when it tortured her, and now the California paradise tortured her becat®se it w winterless. Even in heaven the angels grew weary of golden and jas per architecture and harp. music and tried to change thelr government. Discontent with the weather was only one of Memfs unhappinesses. Her ambition was ruthless and her critical faculty rebuked her. She prayed for opporunitles for bigger roles and blushed at her obscurity: yet when she saw her finished scenes she suffered Cirefully because she had done them. so ll. When her colleagues applauded her she said her true thought when she an- swered; “It could have been done so much better. If only we could re- take itt" She was living the artist's life, goaded to expression, rejoicing in ut- terance and afterward anguished with regrets that she had not phrased herself a little differently. As with every other artist in the world's history, her personality, her preferences, her very face and form offended many people. Nobody ever Pleased everybody. She overheard harsh criticisms or they were brought tg her one way or another. They hurt hen cruelly, and the more cruelly since it wags her nature to helleve. them justified and even a little tess than harsh enough. Some happier natures than hers could always protect themselves by saying that the critic had a per- sonal spite, or was a failure venting the critic's own disappointment, or was too shallow to appreciate, or had been bribed. But Mem never could wrap her wounded soul in such bandages. She felt that the truth was worse than the worst she heard. She could al- ways find some fault !n her achieve- ments that the oritics had over- looked. She could not retake her pictures, however, and when occasionally, a scene had been shot over again and she could correct some fault, she al- ways found another gne, or more, to replace it. Obscurity was a further anguish. She suffered because so few people had seen her pictures, and the hard times that diminished the audiences lodked Ike a personal injury to her in her artistic cradle. And then she had a stab of another sort, She learned the curse of suc- o One of her pictures was shown at the California theater in Los An- geles, and shoe sat in a vast throng and saw with pride that people strange to her were leaning forward with interest anG devouring her with thelr eyes, She saw a fat woman aniffie and thought it a beautiful tri- bute, She saw 4 bald-headed man sneak a@ handkerchief out and, pre- tending to blow his nose, dash bis shameful tears nway, And that was beautiful to her with a wonderful beauty, She played a minor role, but ahe heard people speak of her the mob went out among the inbound mob crowding to the next showing. ‘The papers the next day in their criticiams gave her special monticn. Bho loved Florence Tmwrence and Guy Price, Grace Lindsey, Iawin Schaliert, Monroe Lathrop—all of those who toned her n word anc’ put her name tn print, A marvelous thing to see one's name in print and with a bouquet tied to it, Sbe had but a little while to revel in this. perfect reward, for in a few|anguish of exactitude attending each || strange to her. & savagery about the very writing. days a ‘etter came to her, forwarded from the studio, The writing on the envelope was When she opened it there was no signature. There was Her heart plunged with terror as she read, T seen your pictur last nite and {t made me sick yore awful in- nasent and sweet in the pictur and you look lke buter wouldent melt tn your mouth but I know better for Im the guy held you up in Topanga cannon wen you was there with that ther guy and took your wedin ring off you I cident know who you. was then and I dont know who he is yet but Im wise to you and all T got to say is Ive got my ey on you and you beter behave or else quit playin these innasent parts you movie people make me sick yore only a gang of hippocrits so bewatr. Mem felt odious to herself, with al! the revolting nausea of evil revealed. There {9 remorse enough for a strug gling soul that knows its own defeats and backslidings, but it is nothing to the remorse that follows a pub: ished fault. This letter was more hideous than headlines in a paper. It was more dreadful than such a pilloried public shame as Hester Prynne’s. It meant that somewhere there was a man in an invisible cloak of namelessness and facelessnéss who despised her and jeered at her sublimities of pur ty. Her highest ambitions wert doomed to sneering mockery. She was thrown back into the dark ages when girls were told that guar- lian devils floated about them as well leering enemies, incubl, succubl her elbow, and, since few &men failed witches, fairies. She could hear such hellish laughter as Faust's Gretchen heard. She longed to find this implore his mercy, man and But how could she discover him? He was a thief and could only disclose himself by betraying his own crime, Yet he felt himself less wicked than she. She saw before her a long life of such attacks, She resolved ta do two things—lead thenceforth a blame: less Ife and play thenceforth only such characters as made no pretense of perfection. She was the more determined to seek a foothold in comedy, in wild farce. She wanted to play a woman of sin, a vampire, anything that would free her of the charge of wear- ng a virtuous maaic. She burned the letter but she could never forget it. She could not wa!k along @ street or ride in a car with- out wondering {f the last man who cast a glance her way might not be the thief who had robbed her of something frretrievable. When she sat in a movnig-picture theater she wondered if he were not the man at her albow, and, ance few men failed to look at her with a trailing glance that caught a little on her beauty as on a hook, she was incessantly thrown into panic. In time she grew brazen and said sho Cidn’t care. .A little later she f4rgot the terror that walked by, but now and then it would return upon her—as often when she was alone as when she was in the rango cf human eyes. CHAPTER LII. The first thing that struck Mem about the business of selling jokes was the melancholic despondency of it. In tho other studios there had been a deadly earnestnes at times, but usually a cheerful informality. | But Ned Ling was in a state of nerves and dismal with anxieties. The first scene rehearsed showed Mem being ardently proposed to by a dapper young juvenile whose grace and beauty were to be the foil for Ned Ling's triumphant ugliness. The| juvenile was instructed to do a sim-| ple bit of business. Young Mr. McNeal realizing that | the scene was supposed to be mildly | funny, tried to play it in a mood of wayety—to “horse” it a little with a slight extravagance of manner and| @ humorous twinkle in his eye. Ned Ling checked him at once, “Cut out the comedy, Mr. MoNeal, if you please! It's all right to be fuunny in an emotional picture, but comedy is a serious business. A joke is dynamite, and if it's handled care-| lessly it will blow up in your hands, and take you wit hit. I want the au- dience to blow up, not you. So carr: that scene as seriousy as you can ‘The criticism hurt young Mr. Mc- Neal, but it warned Mem. She went! through her own business with a simple matter-of-tactness as if it had no humor in ft. This was because she did not know how to make it funny. To her amazement, Ned Ling| cried out: | “Great! Perfect! Play it straight! ‘The audience wants to laugh at your expense. Don't let ‘em know you know you're funny, or you're gone.! But Mr. McNea!, I must ask you not| to crab Miss Steddon's scene.” i “Crab the scene, sir? What did/ I do “You moved." “Don't you want me to move?” | “Never. Not when somebody else fs getting off a point. You can kill half or all the laugh by distracting at- tention. An audience can only see one thing at n time—get one idea at a time, You've got to ship ‘em your Jokes like a train of box cars. You can’t jumble ‘em or there's a wreck. When Miss Steddon's at work, you freeze. And Miss Steddon will do| the same when it’s your turn, And, when I'm with you I'll murder you !t| you move an eyelid when I'm spring- ing something. And you can murder me if I breathe during anything of yours, And one thing more. Watoh| out that you don't spoil your own comedy by moving the wrong part of |. your anatomy. I can kill the best face play in the world by moving my feet or my hands. I can kil the work of my hands by rolling my eye. Ro: member that! Comedy is the most sol-| emn business there i \ Mem was amazed, dismayed at the little bit of silly wit. a year of meditation spent on |arose and PAGE THREE } << She had cap- tured her tears and her dramatic cli- maxes with a rush. But wit had to be stolen upon, prepared, and ex- Ploded just so. Ned Ling at lunch time told her of one idiotic Incident. He had nat got it right yet. It might not be ready for t Picture or the next. Some day Jt would come just right, and then it would appear Ifke an improvisation of the movement. He was especially delicate about the broad bits. He was a lover of coarse Jokes; he loathed the Puritanism that gave them an immoral quality. Yet they would not have been half so funny or perhaps not funny at all if it were not for the forbidding of them, just as nakedness would have no spice or commercial value, and would sug- gest no evil thoughts if it were tg- nored or made compulsory, or if the Wrongheaded moralists did not sur- round it with horror and give it the fascination of rarity. Mem suffered acutely from Ned ‘s discussions of risky humor. She ver heard such talk, She was Ike a trained nurse getting her first glimpse of Ife through the eyes of a doctor, learnng not to swoon at the lifting of the vells. Ned Ling had a doctor's impatience of prudery, the same contempt for the viclous indecency of what he called the nastynice. He jolted Mem hor- ribly but he shook the furniture uf her soul into more solid places. Like a nurse, like a woman doctor, Mem was far more decent after this course of training than before, But it took all her nerve to keep from win ing, from protesting, from taking up that obsolescent woman's weapon, “How dare your’ She learned in time to laugh whole- heartedly, like a man, at the coarse verities. She was not educated up to Rabelais. Few women have yet gono so high in the upper humanities. She would never love the great vul- sarities but she was emancipated from the smaller squeamishness, the wide- had eyed doll! mind, and the Kate Green- away Innocence, That was why, perhaps, she could revel so wonderfu pera ly in “The Beggar's when she saw It. of It was the first opera she ever aid see grand or comio. Not even a mu- sical comedy had passed her eyes and rs, Her father did not believe in opera, and if he had his way Mozart, Verdi, and Wagner would have becn as dumb as Shakespeare—for ke ab- horred the playhouse, too. The cata- logue of his abhorrences was unend- ing. He abhovred almost everything human that he could think of except when it was twisted into a form of prayer. He liked opera when it way disguised as oratorio and the singers wore their own clothes insteat of evil costumes. He liked plays about Santa and he vaguely approved t le plays the church had fos- tored, since he never dreamed how in- decent many of them were. He was boginning to admit that motion pic- tures of educational or religious pur- pose might atone for thelr sins. But Mem would as soon have asked permission to go to a dance as to a theater in Calverly. Los Angeles had, for a city of its size, a minimum of theatrical enter- tainments. The long haul across the deserts made it prohibitive of late years for most companies to visit the Pacific coast. She had seen a few plays given by the city stock com: panies and by the Hol'ywood Commu- nity Players. She had even dragged her mother to those devilish amuse- ments and brought her away with- out a sgiff of brimstone. Her acquaintance with the world was almost exclusively of the movies, movish. Like the people of all other trades, when the cinemators had a free evening they spent it in more of the same. The picture houses were frequented by the picture people— of whom thre were thousands in Los Angeles. Her first opera was curiously the last opera one might be expected to see at all in her day. Somebody in London had been in- spired to revive the sensation of 1728, It had run for a solid year in the new London and another season in New York. Its ancient art had glist- ened like a Toledo blade. It made the epigrams of Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shaw look old-fashione An opera whose hero was a thief and whose scenes were sordid—the Rayest of operas, it dumfounded Mem as it had set old London aghast. There where the rival Itallan com- panies had made war fn an other- wise undisputed field, it suddenly laughed them off the boarcs drove Handel into bank- ruptcy, drove him to such despair that he went to Ireland, and, casting about for something to do beside the operas that were a closed career for him, tossed off in three weeks—“Tho Messiah” and became immortal as a religious force. Thus much Mem tqarned before the curtain rose. After it was up she learned to laugh uproariously at the utmost delicacies of indecency. It made an earthquake in Mem’s soul to sit alongside Ned Ling and Msten to the scene where the heroine hor- rifles her parents by announcing her marringe to a handsome young man horrifies them not becau: she wished to marry a highwayman, but because she wished to marry at all, except possibly some olf man for financial reasons. Mem was aghast when they ridt- culed their daughter's talk of love: at length the father protested, “Do you think your mother and I should have Mved comfortably together so ‘ong if we'd been marrigd?” (Continued t Sunday.) —— Bed bug juice; guaranteed to kill vermin: will not stain bed cloth- Apco Products Co. Phone 285. all ing. Trees and Shrubs Have you bought your trees and three weeks until a car will be shipped. Order imme- diately or it will be too late. 1. PUNTENNEY ursery Co. Phone 760)