The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 10, 1906, Page 7

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

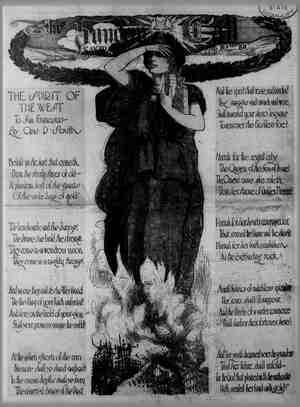

————————— S | { Peace is A L ng. Harry Rowe . New York composer, com- sed sic for the hymn as long ago L is in the same key and eas Dykes’, though r n and foliows more se wi re flexibility the rhythms of the poet. For ano solo and gquartet e Shelley ng is abs utely without the drone- sality so beloved of certain goers who delight in nasal plety ere is climax of a sufficiently ex- racter at the refrain But a hou me on where ingenious tion produces an admirable g “So long Thy power” is also conception. - The closing, with >nies, g the less x the better e f leton often tiives e full fleshed composition p on is very simple. That r its popularity. But it | e exgquisite music of the poem, eiled supplicati to the Father and its somber note 1f concealed despair wh carry s b the heart. Only in the| here a major affirmation; that is reached the mood is in nor key Néwman compeosed the hymn Sunday, e 16 He was still in the rch of England, an ordained clergy- n, and health when he wrote But his own words should be read i went down te Sicily without com- at the end of April. I struck nto the middle of the island and fell 1 of a fever at Leonforte. My servant thought I was dylng and begged for T QAN FRANCTISCO SUNDAY CALL. I gave as he Hem, not die.’ for I ht; 1 haye sinned have r been meant. was lald T d I left for Palermo, tak- Before ne have out what I nd re for near ree weks. f May s fof the my inn on the morning bed ser- sked wer hy My we be- w e week in t Straits of was writing the whole of voung Newman's ersity. Tempest amid the lovellest scepery in Europe, » pen his immortal vérse. en much in metrical form from the Past!” as Dr rry says, “belong to the known in spiritual writers as the of the soul’” The sea Magno,” comprise some five poems written from $32, until he left Marseilles, ] Lead, Kindly Light” Barry suggests that it the march of the tract- It is pure melody, ve peful, strangely not un- tanzas which Carlyle has made ar to the whole English race, the ‘Mas Song’ of Goethe, In its sublime sadnes 1 invineible trust. Both are psalms of life, Hebrew or orthern, chanted in a4 clear-obscure. ere faith moves onward heroically to the day beyond.” It'is worthy of mention that at Yalermo, while visiting numerous churches, Newman wrote, O wat thy creed were sound, thou Church of Rome examination that saw strange modulations dozen years afterward an a The tractarian movement seems to us, after a half century and more, like Old, unhappy, far off things And battles long ago, { But 1t center stirred in Great Britain to its the third decade of the nine- century, and its wavelike im- petus, set in mouon by John Keble, who was, Newman said, the true author of t tractarian movement; Hurrell Froude, “thesbright, the beautiful,” John Henry Newman, Pusey and others, was felt an every Christian coast of the Mozley called it “that potentous of time, the ‘Tracts for the mes,’” It meant much for Newman therefore means much to-day for coreligionists. However, let us | glance at Newman's ancestry. Father | ~arry, whose study may be censidered within its scope as definitive, te.ls us that John Henry Newman (born in London, February 21, 1801) was the son of John Newman and Jemima Fourdrinier, Dutch and Huguenot stock. p The father, like the father of Robert srowning, was engaged in the banking business, was an enthusiastic lover of mausic, of Shakespeare and an admirer of Benjamin Franklin. The original name was spelled “Newmann,” and, as Barry writes, “was umdcrstood to be of Dutch origin, and its real descent was Hebrew.” John Henry Newman's cast of features was markedly Jewish— teenth globe. | birth B | and his 14 tpes, | i | | his best portrait is the etching by !R:\]onfiantl like Baruch Spinoza, his was “a god intoxicated” soul. He pos- sessed. that gen.us for faith to be found only in the loftiest intellects or among the lowly of spirit. Yet beyond his | uncompromising devotion to his deity and a certain sublimity of style and utterance-+ Matthew Arnold has spoken ' o1 the sublime style as truly Hebraic— coupled with a live and prefound | quaintance of the Scriptures, there was nothing else distinctively Jewish in Newman, That he probably had never read the “Ethics” is Barry's belief, and we know that he did not manifest the slightest concern in the “higher criti- cism,” in Feuerbach, Strauss, Rehan or the divagations of the 'Tubingen school. Indeed, for metaphysics Car- dinal Newman never betrayed by any allusion that he had troubled to study Kant, Schlegel, Fichte and Schopen- hauer. With the robust Goethe he | would have agreed in his detestation of all “thinking about thinking,” as the German poet termed the philosophic schools of cobweb and moonshine. But he knew Aristotle and read deeply in’ Thomas of Aquinas, thbugh he did not fail to reveal his love for his favorite St. Athanasius when he asked the late Leo XIII not to forget |that name in the revival of the | Thomist cuit. | He knew the Bible almost by heart as a boy, and his career at Oxford was brilliant. There he became the center of a distinguished group. He came |under the influence of Richard | Whately, afterward Archbishop of | Dublin, and a famous logician. Whate- ly, Newman acknowledges, was one of |the great formative influences of his |life. That they parted company af- {terward did not prevent the younger man from paying a most eloquent tribute to his early preceptor. Hurrell Froude was a brother of the historian, a young man of siugular gifts and a captivating personality. Froude in- in troduced Newman to John XKeble, the | sweet-voiced poet of the “Christian i\'enr." Froude once said: “Do you know the story of the murderer who had one good deed in his life? Well, if I were asked what good deed I had ever done I would say that I had brought Keble and Newman to under- stand each other.” These were the three young spiritual guardsmen who took up the desperate | fight against evangelical Christianity, | All three were loyal to the Church of | England, per se; but they were deter- |mined to pierce the shell of rusty | traditions, and search for the very kernel of their faith. This resolve led them afar. Keble's “Christian Year” FROM THE DRAWING By | GEORGE RKHMOND. R . | made its appearance in 1827. Newman |later wrote of its author: “Keble did that for the Church of England which | none but a poet could do; he made it poetical.” Dr. Puséy joined the trac- tarian movement when it was well under way. He had lived in Germany ind was well acquainted with the writ- Ings of the liberal theologians. And he clung to Tractarianism, refusing to follow Newman on his via crucis. In 1832 Archdeacon Froude want to the south of Franee with his ailing Hurrell, and his friend John Henry Newman. It was on that trip that the latter composed, “Lead,, Kindly Light."” He re- turned to England, to Oxford, and heard Keble preach his historical- Iy celebrated sermon in the university pulpit. It was published, bearing the title of *“National Apostasy.” That July 14, 1833, Newman ever afterward held as the true start of the religious movement. Newman . wrote the| first tract, “Thoughts on the Ministerial Commission.” The bill for the sup- pression of the Irish sees was in progress and the souls of these young divines raged against the liberals. The series of tracts began September 9 and lasted until the feast of the Con- version of St. Paul, 1841. These dates, son, with the whole of the interesting stories, may be feund not only in Mouzley, but in Alexander Whyte's appreciation of Newman, written with rare fidelity to the wanderful man's memory, though not in sympathy with the faith he espoused. England was aghast at the bombard- | ment oY tracts, and there were hard words flung at the audaclous reform- ers. Newman's sermons in St. Mary's became a rallying point for all the fervid and impressionable youths of Oxford. As a pulpit orator he has been described by Principal Shairp. “Simple and unostentatious was the seérvige at St. Mary's when Newm was the preacher,” says Shairp. * pomp, no. ritualism, nothing but the silver intenations of Newman's magic voice. His delivery has this particu- larity—each sentence was spoken rap- idly, but with great clearness of in- tonation, and then at the close of every sentence there wids a pause that lagted for several seconds. “Then another rapldly but clearly spoken sentence, followed by another pause, till a wonderful spel] took hold of the hearer. The look and bearing of the preacher were as of one who dwelt apart, and who, though he knew his age well, did not live in his age. From his seclusfon of study and ab- stinence and prayer, from habitual dwelling in the unseen, he seemed to come forth that one day of the week to speak to others of the things he had seen and known in secret. As he spake how all the old truths became new! How they came home with a meaning never felt before! The subtlest Cox of truths were dropped out as by the way in a scntence or two of the most transparent Saxon. What delicacy of style, yet what grand power! How gentle, yet how strong! How simple, yet how suggestive! How homely, vet how refined! How penetrating, yet how tender-hearted! in which all this was spoken sounded to you like a strain of unearthly mu- | sie.” Dean Church once wrote that “Dr. Newman’s sermons stand by themselves in modern English literature; it might be said, in Hnglish literature gen- erally.” James Anthony Froude, prejudiced, often willfully clouding historic facts and religious issues, has left a finely etched portrait of Newman at this time. | “His appearance was striking. He was above middle height, slight and spare. His head was large, his face remark- ably like that of Julius Caesar. The forehead, the shape of the ears and npse were almost the same. I have often thought of the resemblance and believed that it extended to the tem- perament. In both there was an or- iginal foree of character which refused to be molded by circumstances, which /a8 to make its own way, and become a power in the world; a clearness of intellectual percepuon, a disdain for conventionalities, a temper imperious and willful, but always with it a most attaching gentleness, sweetness, single- ness of heart and purpose. Newman's mind was world wide. * * * His natural temperament was bright and light * * * a sermon from Newman was a poem.” The above was written in 1881 after the smoke of the conflict had cleared away and by a man who can hardly be called a friend of New- man, as we shall presenc..y see. It is well to quote the testimony of New- man’s adversaries. No one, then, ever doubted his su- preme intellect except Thomas Carlyle, who once said that Newman hadn't the brains of a rabbit. The validity of this assertion has been challenged. It is to be hoped that for the sake of Carlyle's memory he never uttered such a speech. Critics are usually remem- bered by their errors of judgment. Years before Newman entered the fold of the Roman Catholic faith there were predictions that he was drifting Rome- ward. He has said that “from the end of 1841 I was on my deathbead with the Anglican Church.” At Littlemere, a retreat for prayer and study, called by Whyte, “a sort of midway house between Oxford and Rome,” Newman wrote a brief letter to his beloved sister Jemima, telling her of his inten- tion to go over to Rome. He left Oxford forever February 23, 1846, This sister occupied the same place in New- man’s heart as did Henrletta Renan in the affections of Ernest Renan. But with a difference, as Father Barry has acutely set for.a in a comparative study of Newman and Renan, printed some time ago in an English monthly. He has pointed out as a parallel that in the month of October, 1843, John Henry Newman came to the door of the Catholic Church at the same mo- ment Ernest Renan left it forever. But Father Barry is hardly fair to the great Frenchman, whose loss of faith was determined by as sincere an impulse as Newman's acceptance of it. . The And the tone of voice | houldst lead me on; 1 loved to chaose and seelmy path, but now Lead Thou me on 1 loved the garish day ; and, spite of fears, Pride ruled my will ; ‘remember not past years. 3—So lon&;’nvy power hath blest me, surg 1t still ill lead me on O'er moor and¥en, o'er crag and torrent, till The night is gone ; And with the moru those angel faces smile, Which I have loved long sm:'e. and last awhile. ~J.8. Newman. cinal Neyman,186] 2—! was nsut ever thus, nor prayed that Thou which the world will never learn. So do not fear that his “Apologia,” lack- ing as it does elements of the luxur fous sins of theatric climaxes, is de- void of other higher and more fearful cembats. Professor William James. in | nis memorable | Experience,” | the | “Varieties of Religious speaks affirmatively of phenomena of conversion. This sudden flood, this interior light which Paul, which Newman. which Pere Ratisbonne and myriad others have | testified to is not the result of an pileptic seizure, as Lombroso would have us believe. Even the unhappy Dostoreoski, an epileptoid. a deeply religious temperament, has testified to | reason, ltcmperamentul differences, too, should | not be forgotten. Imperial as was the intellect of Renan, there was in him a decided streak of worldliness. He had not the spiritual fire of Newman, | master though he was of French prose. | The Kelt-Breton predominated, while with Newman there is something of the | sexlessness of an archangel. To eall | one Caliban anu the other Ariel is hardly fair to either. The sisters of the two men were, as we may See in their correspondence, guiding stars— |to a certain point in the ecase of ! Jemima Newman; to the last ditch of renunciation on the part of Henrietta Renan. What had hapenedl to the soul of |John Henry .Newman? Barry truth- | fully asserts that all great literature is autobiographic. Newman forsQok as untenable the via media, and his erudite study of patristic literature sent him in that direction which Re- nan, after delving in the same ma- terial, had forsaken. But what the In- commensurable change! What form | was this psychic phenomenon which | we call “conversion”? Newman's ewn | “Apologia pro Vita Sua” is the an- 1 confess this' to be my favorite iawer. |book of all confessions, antique and | It holds In the affections of | modern. | Roman Catholles the same place that “Pilgrim’'s Progress” does in the other camp. As in Bunyan's doughty book. Newman has “spilled his soul"-—spilled it with a candor and sweetness that will make his phrases classic as long as English, is read. St. Augustine’s confessions have always seemed to lean heavily on his sins, as do the extraordinary revelations of Karl- Joris Huysmans’ “En Route.” We get the color and perfume and the bravery of sin; likewise we are dragged through the mire, and the drab and gloom set off, artistically, the flam- boyancy of the pictures, After Huysmans' “L'Oblat” it woyld be absurd to doubt his sincerity, very much fortified by the publication of “The Cathedral” And no doubt Mes- sire Anatole France Is half right when he announces in his gay, charming voice that your great saints are manu- factured out of very sinful souls. Yet without yielding an jota of interest to either Augustine or Huysmans | Newman's “Apologia™ is the truthful narrative of a soul in search of divine |adventures. Sinless in the grosser sense Newman was. His pure nature abhorred the sensual. For him the prizes so madly fought for by men— ambitions, political, intellectual, ar- tistical, social or financial—were as it non-existant. He saw one thing clear- ly, and that was the relation of his soul to his God. A man fer whom this tremendous fact was a fact, and not the dream of a dilettante and a trifler, there could be no other course to pur- sue and no dalliance with the painted illustrations encountered on his earth- 1y pilgrimage. He could ardently ex- ‘As the heart panteth after the His life long was a pursult true path. And aristoerat, supersubtle thinker as he was, he, un- like Nietzschke, never despised the “herd.” It was his self-imposed mis- sion—a religionist would call it God imposed—to proclaim the light to this same herd. This he did humbly, brave- 1y, lovingly, untiringly. That his sooty lerdship spins traps for the purest minded we need not doubt—the devil can quote the Secrip- tures—and doubtléess John Henry New- man had temptations, waverings. agonies . and mental crucifixions of Newman, a mystic and hard sense of the gen- the difference. with the cool. uine mystic, has told us of his com= version in matehless language. His own illative faculty (vide his ‘Grammar of Assent”) is but a logical instrument for the apprehension of the higher forms of theught—the surcroy- ance, to use Professor James' words— the logiec of belief, the other side of the sixth sense of the mystic. Yet this thinker po: the brain of a schelarly Englishm trained, calm. above all wedded to the concrete (another Jewish trait. says Barry). It is noteworthy that his style, sober, luminous and sinewy. seldom swerves from the reality. Reality was the watchword of this dreamer. His arsenal of polemics is filled with illustra- tions borrowed from the visible world. Not a rheterician, as was Bossuet, he prefers the simplest Saxon charged with the simplest images. The genesis of the “Apelogia” was this. Canon Charles Kingsley, possi- bly prompted by James Anthony Proude. openly accused Newman of in- sincerity; worse, of untruthfulness. ‘Truth for its own sake had never been a virtue with the Roman clergy. Further, Newman informs us that it need not, and, on the whole, ougit not to be,” ete. Newman always proved his fighting blood when face to face with the eneniy, and his denial was so strong that . Kingsley publicly apologized, But Newman was not placated. Be- tween April 21 and June 2 he put forth ‘he seven parts of his apology, and the ook was like a tropical thunderstorm n a murky night. It cleared the air. It also drove to the wall his opponents, Che hard logie, the modest and inti- mateée revelations of a soul in the mak- ing, the magnificent marshaling of proofs and the inexpugnable summing up discevered another Newman to the éyes of his countrymen, After that there was little talk of Newman “the Jesult.” Of his style there is nothing new to be sald. It is the most flexible, flowing and exquisité in English literature. His is the “still. small voice™ of our master tongue. Out of his writings nine volumes merely will endure by their 3heer force of style, In its clarity his prose makes Carlyle’'s fuliginous; even Ruskin seems strange and exotic. The nearest approach to it, though without intense spiritual life of Newman, Thackeray—Thackeray, of whom it is the fashion in these days when Eng- lish prose has become a strident or- chestra, to eall colorless and flabby! Newman's prose is the perfection of grace; it {s finely fibred and rhythmie, as only a delicate musician can be rhythmic. It must not be forgotten that Car- dinal Newman was a violin player of merit and his life long an excellent musician and a cultivator of that spe- clal form, the string quartet. In the domain of peetry it is onmly necessary to mention his “Dream of a poetic drama, & 1d of the human soul, an “in- drama, written when Maeter- terior™ linck was in the cradle. Its lofty im- aginative qualities, its musical verse are sybordinated to the idea, a mystie idea worthy of Dante. New York has heard the setting of this true mysteny play by Sir ~Edward Elgar, whose music, while it betrays a leaning to Lisat and Richard Strauss, has its flashes of insight and originality. Newman was made Cardinal of St. George by Lee XIII May 12, 187). He died August 11, 1890. “Ex umbris et maginibus in veritatem” Is his own se- lected epltaph (“coming out of shadows inte realities””). The answer to his “Lead Thou Me On" had been made. He died in peace with his soul, the ona victory in this vale of unrest worth the iwccomplishment. Has he not sald that - tor hin there was “rest in the thought of two, ard two only. absolute and luminous self-evident and my Creatos?” -~