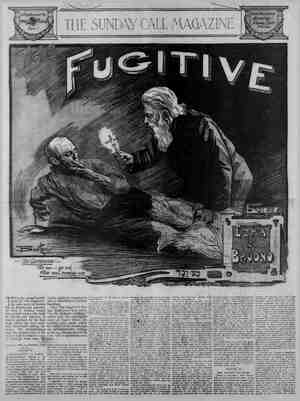

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 19, 1904, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

o N .FRA {CISCO - SUNDAY CALL., wes onpe long and extremely alley. I stopped before the first stood behind & broad rustic- from which a glimmering ne forth, determmed to beg-a ¢ for the rest of the night. As :p to the gate several dogs gan such a ferocious barking t sed, fearing to risk what Yrtle ) remained in me. Recalling & k f exorcism I knew when a child, tried it on these raging animals. But they s ot to ming my incanta- tons umped over the gate, and the rest made as if to follow. In this r | sttuation I thought the best ex- r ,» would be to ery for help. I.did s nd a peasant, half-naxed, opened the door of the hut. ‘s that?" he asked, as he the dogs. m that I was a wanderer and have lodging overnight. 3osje Mol (my God),” he said, g himself. “On a night like And after e had scrutinized me ured to himserf: “He's nc be as he shelter to or Jew,” he the gate for me. entered his hut. It was of the same style as those of most muzhiks; one square, earth-floored room, the un- no one, eald, plastered walls and low ceiling of which were black with smoke. One- fourth of it occupled by a large brick oven; another fourth takxen up by a large bed which was commonly known s the “family bed;” and the remain- ing space filled by 2 long, unpainted table with a rough bench along each side of it, a pall of water, a manger for the pigs, and = wooden dish for the rabbits that were crowded together in & corner. An oil lamp burned before 2 small image of Christ, praced beside the window, or rather the small square hole which served as one. A suffocating stench pervaded the room; however, the warmth bréught new life into my benumbed body. Four or five of the occupants of the bed raised their heads, and I noticed by the light of the oil lamp that they were of both sexes. The good muzhik set black bread, salt and water before me, and asked me whether or not I was hungry. I thanked him gratefully, and said all I cared for was a place to sleep. “There, 8jldotchick (little Jew), is a warm spot,” he pointed with his finger st top of the oven. And he un- ceremontously raised the large blanket and crept under by the side of his y imbed upon the high oven and ng to lie down, when I noticed thing stirring there. And I was more startled to find a partner—a 1 was going to slip back to the fioor, but she said, “There is plenty of room here,” and innocently moved aside. The morality which had been inculcated in me did not permit me to accept her courtesy, and I offered as an excuse that it was too warm. So I lay down on one of the benches. The soon feil asleep again, though ;I was, sleep My mind owed a trdin of feverish thoughts roused by the events of the afternoon night; and besides, even had my mind mot been active, I would have been kept- awake by the deep groans hat arose mear me, which, however, did pot seem to disturb the other occu- pants of the hut. After my eyes had become accustomed to the semi-dark- ness 1 discovered a man lying upon a truss of straw on the ground but a few feet away from me. The dim light be- the image of Christ cast a yel- h glow upon his emaciated coun- tenance. He lay covered with a tat- tered sheepskin coat; his head rested upon a dirty straw cushion. His eyes were closed, his mouth haif open, and he was breathing slowly, a groan com- ing forth with every breath. “Basil!” he cried out, after I had been in the hut for perhaps & quarter of an hour. Nobody answered; loud snoring rang h: the stenchy room. I could now heer the man on the ground breathing heavily and tossing about restiessly. Several minutes passed. “Basil!” he cried agaln in a hoarse, feeble voice. The only answer was a fami exhausted uld not come to my eyes. but w £ low chorts of snores from d¢he “family bed. “Besil—I—am—dying.” A\ “To the devil!” my host muttered, as he jumped out of bed. “What do you want, Michael?” “Brother"—Michael made a hard ef- fort to speak—"brother, bring a priest. I am dying.” Basil scratched his head as if unde- eided what to do. He looked good- natured, but he appeared to entertain some doubts as to whether his brother bad reached the point when a priest is . He uttered & curse good- , as if his brother's request was merely an every-day Jjest, and said: “Oh, Michael, you won't die yet, and I'll trouble the batiushka (little father) for nothing.” Michael emitted a deep groan. “God knows whether—I'll live long enough— to see the sun. Call the batiushka.” I shuddered. Basil scratched his head again, muttered a few curses un- der his breath, and put on his heavy fur coat and his sheepskin hat. “I know you will trouble the batiushka for nothing,” he sald, and slammed the door behind him. The rest of the family paid no heed to the dying man. “My confession—my confession,” he murmured feebly, as he tossed about convulsively in the agonles of death. Once he rose by a sudden impulse to a sitting posture and screamed: “Oh, the priest! Confes- sion—my confession!” Nobody seemed to have heard him: the family was peacefully snoring; a few pigs under the family bed grunted and squealed restiessly. It must have been a little before day- breek when I heard approaching foot- steps. Soon the door opened, and Ba- £l entered with a corpulent oid man, whose long, white hair overhung his broad shoulders. “Here, batlushka,” Basil said rever- enttall pointing a finger at his brother, writhing with pain on the ground The batiushka remained standing in the middle of the room, leaning on his heavy gold-headed walking-stick, The host produced a long, thin lath, which he stuck betweéen two uncemented bricks of the oven and then lighted. The flaring torch cast a mournful light over the whole room, and brought out the cadaverous fece of the dying man with ghastly distinctness. “Michael,” Bas!l said to his brother, “here is the batiushka.” The dying peasant made an effort to raiee his head, but fell back upon the truss of straw. There was a convul- sive twitching of his emaciated coun- tenance, his unshaven chin trembled, his frame shivered. The priest crossed himself and with eves uplifted murmured: “May the Father, Son and Holy Virgin bring you salvation.” “Batiughka,” the patient began in a low, guttural voice, his eyes ‘moving wildly—"Batiushka, I wish to confess before I dle. I sinned heavily—heavily —heavily.” Here he collapsed. “Confess and bring salvation to your 50 This word of encouragement from the priest seemed to give strength to the dying man, and though shivering vio- lently he proceeded more easily: “Oh, batiushka, my great sins have preyed upon my life for the last ten years—: ever since 1 was seized In the devil's clutches!"” “Contess and lighten your burdened heart,” the priest encouraged him again, making the ®ign of the cross. The dying man seemed to be so agi- tated with his forthecoming confession that fgr some time he coutd not speak. Then he resumed, & gasp after each choppy sentence: “Batiushka, I wish my sou!l to go up to God. T want to tell you all before I die.” Another long pause. “About fifteen years ago I worked for a Jew. His name was Yudel Abramowitch.” I sat up and gasped for breath at the mention of my father’'s name. i “He treated me well, he did. But the devil got me in his clutches, and I took to drink, My master gave me many warnings, but the devil would not let me stop. Yudel told me to leave—I couldn’t blame him. J hung around the taverns, helped them & littie, got plen- ty of drink.” He pausea again. I drank more and more. I was kicked out from every place. Then I got to be helper to the sexton in the syna- gogue. “One day a burgiary occurred next to the sexton’s house. 1 was arrested. I was innocent, batiusnka. They brought me before Sledevatel Bialnick. He cross-examined me. He could not get anything out of me. I was inno- cent and knew nothing of the burglary. We were alone in his office—Bialnick and I ‘Michael’ says he to me, Tl have to diredt you. Your record of the past shows that you committed this crime.’ And then says he: ‘But I'll help you and set you free if you'll do a trifie for me!’ ‘Yes’ says I. ‘Do you know Marianka, the washwoman® says he. I knew her well; she was a pretty girl; people talked about her being Bialnick's mistress. ‘I want you to go to her house quite often,’ says he, ‘and tell the people she is your mis- tress.” ‘Yes,’ ys I, and I was set free the same da He rested again and then went on: “A few months later Marianka gave birth to a child. The sledevatel gave me money for Marianka; when I gave it to her she took it ana cried. Then one day Bialnick called me to his office and asked me to own the bastard as mine. I did not object. What differ- ence was it to me? So everybody said the child was mine, and I laughed. Several years passed. I had plenty to drink and plen'y of money. The slede- vatel wag never stingy. The brat grew like a sapling—the very image of Bial- nick.” For several minutes he struggled hard for his breath. The priest was like a statue. My heart was throb- bing and my head was whirling. “A few weeks before Easter Blal- nick sent for me. He asked me how I liked being called the father of an- other man’s. child. “Would it not be best to get rid of this bastard,’ says he—'better for me, better for you? I said it would. ‘Why should one not make an énd of it?’ says he. I told him that would be a risky business. ‘We could transfer it to the Jewish ac- count,” saye he. I did not understand. He sald that Passover was near, and didn’t I know that Jews kill Christian children for the Passover. ‘Some Jew would be blamed for it says he. ‘Why not Yudel Abramowitch? I said he was a good man; he had been very good to me. ‘Michael,” says he, ‘you are a fool. Don't you know the Jews killed our Bavior and nailed him to'the cross, and they are still sucking our blood? Yudel Abramowitch is a bloodsucker,’ says he. ‘He’s skinning the peasants alive, and he got all his money by his Jew tricks and has a mortgage on all my property.’ All the time he had poured out glass after glass of whisky—and oh, batiushka, I promised!” Michael fell back on the straw and tossed convulsively. “Go on—go on,” the batiushka en- couraged h “God will forgive you. You have only been the imstrument in the hands of a wicked man.” “Yes, yes, batiushka, omly an Instru- ment, blessed batiushka,” wept the dy- ing peasant. “Our Savior knows that I did it in his name, as Bialnick told me—" “Not in his name,” struck in the pious priest. “It was in Satan's name.” And he made the cign of the cross over his breast. “Yes, batiushka, in the devil’s name. And while I was in the devil's clutches I coaxed the child into the woods. I cut its throat and hid the body in the synagogue.” He ended and ay fighting for his THE last breath. “Oh, batiushka!” he gasped, clutching the priest's hand. But not another word. Incoherent babbling was all ‘I could hear. The priest took a cross from his pocket and pressed it to the dying lips. I rose unsteadily to my feet. The members of the family were rising one by one; the rabbits, crowded together in a corner, were munching withered cabbage leaves; the pigs ‘under the “family bed” squealed and grunted; the chickens cackled-in the coop under the oven—it was daybreax already. Without so much as a “thank you" I slipped out of the hur, leaving the peasant in his last gasps and the -priest whispering words of absolution in his ears. Vaguely I marveled that chance had brought me to this hut on just this night; vaguely I thought or life being a chain linked of chances; vaguely I recalled the incidents of my’ life and the chances that linked ‘them together. Little by little new-'thoughts, new sen- timents took possession of me—strange thoughts, wild sentiments, This Bial- nick—this supposed = benefactor. A flerce, savage desire for vengeance— vengeance at any ‘ccst—burned within me. And suddenly, like a streak of lightning ripping the €louds, the re- niembrance of a face recurred to my mind. Ah, Katla! Katia! Honey from a stinging bee. CHAPTER XIL BACK TO MY OWN. My first impulse as I left the hut was to go back to the sudya and tell him all I had discovered—tell him that I knew he was the cause of my father's death, and that the innocent blood of mypoor mother was on him; tell him that T was not yet strong enough to kill him, but should find vengeance for my parents’ blood. But after I had gone a few paces back over the road that led to Zamok 1 realized ‘how useless such a step would be,, With thesé thoughts still torturing my brain I returned, and as if fearing my own will I began to run. The weather had slightly changed during the night; the hail and snow had ceased falling, and the warm caress of the rising sun turned the fur- rowed fields into splashy mud and slush. At every step I could scarcely free my foot from the slimy mud, and my boots squashed like croaking frogs. I struggled along the mail road, mel- ancholy, my head bent over my, chest. Gradually my fieree sentiment against Bialnick gave place to a different feel- ing, and my heart began to throb‘wvio- lently, At first this feeling was vague, almost incomprehensible, but I was soon conscious of a sweet and alluring alr chiming in my ears; a soothing sensgtion passed through my frame; a charming picture presented itself be- fore me—Katia! I felt the thrill of hope as this vision filttea through my mind. Again my heart was burning with a’craving desire; again my blood was flowing warmer and swifter; again an almost irresistible impulse was fore- Ing me back to Zamok—go back and read of the same book with her; feel the touch of her locks against my burning- cheeks; hear her say again, “Why, you foolish Israel, then I'll marry you'—and forget—forget my father and her father and everything that embittered my heart! But I realized that to return was Im- _possible; g0 I tramped painfully, dog- gedly on, my legs growing heavier and heavier. Presently the faint jingling of a bell behind me broke in upon my hopeless thoughts. Turning about, I beheld a long, mud-covered kibitka, the top of which was a quaint combina- tion of patchgs, drawn by two skinny, bespaettered horses. I stopped and waited its approach. But just before it reached me its front wheels sank half-way to the hubs in a water-hidden rut. .. “Phmtz—phmtz!” the driver encour- aged his animals. They pulled with all their strength, but the wheels, evident- ly pot well greased, creaked without rolling. “Would that the black cholera had you, you limping old mares!"” This the driver followed by a 1ong string of oathe, jerking the reins and whipping the poor beasts mercilessly. Several passengers jumped out of their own ac- cord, and this so lightened the vehicle that the horses, by a sudden pull, dréw the kibitka creaking out of the rut. “Nu, pritzim (noblemen),” the driver accosted his passengers half-sarcasti- cally, “get a move on vou. You think my llons (tapping his horses with his _whip) can carry you a thousand miles without a stop, hey?” V. “We dragged slowly @nough all night,” complained one of the paasen- gers from within the kidltka, “and If © we keep on moving at this rate we'l] scarcely get to Javolin at sunset.” “If you please,” the driver rejoined with unsuppressed wrawn, “I'll not drive 1y poor horses to death on your aceount—no, not for seventy-five co- pecks. At this time of the year I should ‘have charged at reast a ruble and a half, but—all plagues on. the other coachmen—competition is fierqe. Well (a little facetiously), you will be- come a rabbi a day later.” Javolin! Who had not heall él!he Yeshiva (seminary) of Javelin? hat @God-fearing mother did not cherish the hope of having at least one son at this Talmudic lyceum? What wealthy fath- er-‘did- not spsculate of procuring a +son-in-law from this center of learn- ing? What shadchan (marriage: broker) did not cast his bait/In this’pond of goldfish? The Yeshiva of Javolin—the gource of prodigies! Javolin now appeared to me like a twinkiing star in a dense nght. My way was pointed me. 1 went up to the driver and asked him to take me to Javolln. “For how much?” he asked pointedly, beating the butt of his whip against his long, muddy boots. I stood abashed, with my fingers fumbling in my pockets as if I were scraping my money togetner. “We will not allow you to take an- other passenger,” remonstrated the one who had before shown great anxiety to get to Javolin. “We hired you for three of us, and already you have crowded in seven more.” “How do you figure. seven?” re- turned the driver. “I agreed with you not to have more thdn thrée men. Do you call this lady with children a man?" He pointed his finger at a small family crouched togethér in the kibit- ka. “Do you call that poor gentle- man,” he sald ‘In a lowered voice, pointing at another passenger, man? Well, I am an ignoramus, but you ought to know that the Talmud says: ‘A poor man is regarded as a corpse.’ Did I ever promise you not to carry a corpse? And now as to that blind gentleman, don’t you know that the Talmud says that a blind man Is exempt from all religious obligations? Now as to this youngster, he is no man, as you can see for yourself.” These jesting excuses pacified the grumbling passengers. Turning to me, the driver said: “Well, how much will you give?* #“I—I~—lost my money,” I stammered, feeling the blood spring to my cheeks from shame of the lie.s “Aha! little fellow,” the driver said humorously, “yeu lost your money, hey? If you're as smart as that you must have reached manhood, and I agreed with these gentlemen to take no more -than thyee.” He laughed heartily as he turned to his passengers and winked. 1 dropped my eyes and wished I might sink through the ground; his jests hurt me, and the passengers stared at me curiously. After a short rest the driver asked the passengers to take their seats, and he jumped upon the box. My heart sank within me as I watched them crawl into the lotg, narrow, closed wagon. I would give anything to be taken to Javolin, but I did not have a copeck. But as I started away on foot the driver called after me: “Where do you live, young fellow?” Tears fllled my eyes. Where dld I © live? ” ‘He glanced at me pityingly. “Jump up,” he sald, and moved aside to make room for me. CHAPTER XIIL THE YESHIVA. When we reached Javolin the other passengers had supper at the inn be- fore which the kibitka had dropped us, but I, baving no money, set cut.imme- dlately for the yeshiva{ Though night had fallen, I needed no guide to it; brightly lighted; 1t towered above the “few hundred low-built, thatch-roofed huts that composed Javolin. From a distai.ce it appeared like a lighthouse, and its reflection cast a vast shadow over the sea of roofs, 1 followed this light. The town was quiet; not a mov- ing team, not a pedestrian, not an- other light to cheer the deserted alleys, not even the sound of my footsteps as 1 was treading the slush—nothing but dense darkness, gloom, isolation. Only once this deathlike stiliness was broken as the door of a tavern opened. But hark! While still at some dis- tance from the yeshiva a sound like that of water seething.over a great dafn reached iy ears. 1 held my breath; 1 put my feet down softly; I strained my ears. As I approached nearer the seminary the gound grew louder and separated into distinct _voices—the sum of hundreds of voices, each pitched in its own key. For a minute I stood in front of the great white building and gazed through the lcng arched windows at the swaying heads and chadows of heads, of shoulders, of opening and closing mouths, and at the waving arms, slightly osecillating lamps suspended on long wires; and I watched the young students, with cigarettes“between their 1ips and long books under their arms, hurry down the score of cut stone stéps and disappear in the many smaill ‘slde streéts that® branch-off the yes- hiva campus. . . I climbed the stairs with awe in my heart, opened the door, and trembling- 1y ‘entered. A bewildermg spectacle Was before my eyes. No less than five hiindred students were in the emor- mous classroom, varying from strip- lings of 16 to grown men with long, un- trimmed beards, sitting and standing on both sides of the long “reclining desks.” They swayea tneir bodies backward and forward, from side to side, llke so many pendulums in a clockmaker’s shop, while they conned their lessons In as .Joud a voice as each pleased, anid in as many different intonations as- the voices that uttered them. Some sang’ Talmudic rules in elastic barytones and modulated alto voices; some recited the intricate, never-ending, hair-spliting arguments in plaintive, imploring notes, and some piped halachas (statutes) in sweet soprano; some laughed and some groaned; some shouted and some hummed in hushed voices; some talked and some whispered; some winked and some stared idlotically—an uproar of Talmudic learning! The sight was purely oriental, unadorned by Grecian art or modern European polish. Among the clamorous rows of stu- dents there were representatives of all climes and of all generations of the race; old-looking, swarthy Arablan faces; delicately cut GCreclan faces; faces with commanding Roman noses; sandy-complexionéd Russian faces; and faces suggestive of Spain and Hol- land and Germany and Poland and of nations unknown. In their thoughtful countenances, their gestures, their ner- vous actions—in everything about these children of a. wandering people— a physiognomist might have read, from. an open book; the same imaginations and poetic’ minds that characterized, in ages long past, their heroes, poets, andl brilllant sages. In dress and physique thé students varied as much as (n their faces. There were men in old-fashioned long caftans, with corkscrew curls dangling on both sides of their cheeks. and in ciothes of the very latest style; not a few appeared wealthy, their faces wearing the expression of the spoiled child. Hale, robust lads with * broad shoulders and piercing eyes were promiscuously discernible among flat-breasted, submissive-look- ing boys. A short, heavy-set man with a small, iron-gray beard and dull face walked between the rows of desks, scrutiniz- ing everybody with his stupid eyes and noting in his little book every vacant seat. He was the mashgiach (inspect- or). He fraquently stopped and spoke to those seated near, as if Inquiring about the absent student. A tall man with sottish eyes, purple nose and curly pelis (ear-locks) foilowed behind the mashgiach, step by step. A few students noticed me standing near the door, but no attention was paid me until the man with the sottish eyes—who, I was told later, was the mashgiach’'s assistant—came to me and asked whom I wished to see. I told him I came to enroll in the yes- hiva. He glanced me over with a sa- tirical smile on his face/ and scratch- ing his left peil said: “Did you bring your wet-nurse and your cradle along with vou This sarcasm cut me to the quick. He saw the effect of his words and hastened to make amends. “I mean no harm,” he said, scratching the same peil. “Qo to the rosh-h'shiva (prineipal), and he will do the right thing by you.” The rosh-h'shiva lived in a luxurious home next to the seminary. I ascended the high porch and was.admitted to a brightly lighted corridor. A tall, handsome young lady, richly dressed, with the dignity of a queen and the arrogance of a servant-girl others who marries her master, came up to me and asked: “Do you wish to see the rabbi?” “Yes,” I murmured. “You may see him in Rhis study— there,” she said a trifle haughtily, and pointed to a large room acroses the hall- way, the doors of which were I stopped at the threshold. A solidly built man of about 70 years, With a calm, broad, square forehead, was stooped over a long table, upon which lay a number of open folios. His un- spectacled eyes skipped from book to book as he turned a-few leaves of « or scribbled a few words on the marg of another. Every line in his fa showed complete absorptiof I st for some minutes waiting for hin take notice of me, but he comtinued bent over the book$, unconsclous of my presence. So, 1 thought it Wi cough. He raised his eyes.. “What do u wish, my child?" he asked in a Denigr husky voice. I told him that I desired to efiter his institution. He stretched out his little fat hand “Sholam aleichem (peace be to you).” he said. “And where do’ you from?"” I knew the consequence If I told the truth. T hesitatad a moment and then gave the name of a small town I had never seen. He was proceeding to question me further, showing a little riger In his tone, when he was interrupted by the young lady I had met in the corridor “Miriam, how is- Teploffka?”’ he asked of her. “Do we get anything from there?” “The collectors scarcely make their expenses,” she replied ‘authoritatively. “And besides, we have no trustees there, and I do not believe that we can allow a Teploffka student any stipend.” I did not know what reply t6 make 1 stood dumb between the aged rabbi and ‘the beautiful young lady (who I afterward learned was his third wife), like a Danlel between two lions. The rosh-h’shiva turned again to me: “Perhaps your father will be able to gend you enough money, so that you won't need any stipend,” he sug- gested. “T have no father,” I murmured. “A yosem (orphan)?* he inquired in a sympathizing tone. “Neither father nor mother,” I re- plied. The rabbl looked at me thoughtfully, curling a few hairs of his white beard about his forefinger. His young wife regarded me with anything but pleas- ure. “Well,” he sald after a-few moments, “present yourself before the mashgiach to-morrow, and if he reports your ex- aminations satisfactory we'll see what we can do for you." “T don't belleve we can give anything to a Yesident of Teploffka,” struck in his wife, noticeably irritated, as if her own money were in question. “T looked at the books the other day and I found that Teploftka never contributed much to the yeshiva.” “A—a—my child” (he addressed his wife also as “my child), the rabbi said softly, we'll see¢ to-mourrow—a—a— we'll see to-morrow.” A few minutes later I was tramping béck through the muday street to the tavern where the kibitka had dropped me. come CHAPTER XIV. MY NEW HOME. The following marning { presented myself before the mashglach, who was also the examiner, and upon his recom- mendation I was accepted and grapted a stipend of seventy-five copecks a week, though Rabbi Brill's beautiful young wife insisted that ¥ty copecks were plenty. Before I was quite settled I sauntered diffidently about the yeshiva. A num- ber of students, who would sneak out as soon as the rosh-h'shiva appeared, were always found lounging about the lobby, with books under their arms and lighted cigarettes Detween their lips. For some young men came here for the sole purpose of being enrolled as students in order :that they might obtain a reputation for scholarship and so have their dowries increased. They would chat, crack jokes, piay pranks upon one another, criticizes the yeshiva officials, make Insinuating remarks about Rabbi Brill's young wife, and were altogether bent on mischief. Seeing me, they began to make me the butt of their jests: A tall, lean fellow, with glasses on his nose, whis- pered to another, loud enough to be heard by them all: “Did this baby (meaning me) bring his mamma along?’ A roar of laughter followed this facetious remark. I blushed, dropped my eyes, and bored my pocket painfully. Immediately a cotled wet towel, thrown by one of the group, struck me in the back of the neck and sent my cap filying. I should have been rurious at this insult, but I had only a desire to sneak away. “Shrolke!"” exclaimed a’'voice as I was picking up my cap. 1 wheeled about joyfully. “Ephraim!" I cried; and we A were straightway clasped in each other’s arms. “A mountain never meets a moun- tain, but one pe~son comes across an- other,” he quoted in Aramaic-Chaldaic. He freed himself ‘and turned to a group of loiterers. “See here,*you fel- lows, you'll find it a good plan to leave him alone.” Without waiting for their reply he led me off to his room, and there we told one another of our ex periences. 1 confided everything him excent my feeling for Katia, a sub- Ject too sacred for me to lay bare even to my dedrest friend. In spite of my deadly hatred agail her father, she was sweeter than ever to me. The same day I obtained lodgings at a poor tailor's for the modest price of twenty-five copecks a week, and I Boped to stretch the balance of my stipend so that it would cover my board and other necessaries. I do not believe my landlord ever had a given name, and if he had I am cer- tain he was unacquainted with it. In the community he was known as Men- ke Shmunke’s—that is, Menke the son of Shmunke. And his wife, who through sonfe blunder .f Providence was made a -woman, Wwas commonly called Groone Menke Shmupke's. Not- withstanding their humble station and names, Groone always talked disdaln- fully of the “ordinary working classes,” and so Influenced her husband as to make him believe that he was a re- spectable baal-h'bes (bourgeois). Menke was a small man who had probably ceased to grow at the age of 12, as is sometimes the case with hard- working children. His Dones were large and broad, and the more promi- nent as the Creator had neglected to cover them with emough flesh; his cheek bones were high and the cheeks