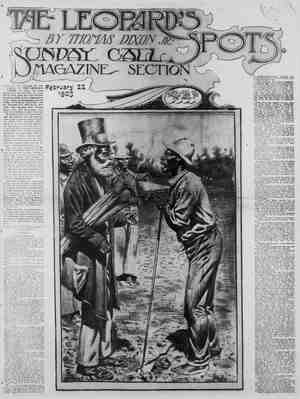

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, February 22, 1903, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

camp followers with 1to sort of Union League meetings, out arms and ammunition tc and what is worse, inflaming passions against their fory ching them irsoicnce ing them for crime.” I'll do_the best 1 can for you, doctor: but I cad’t coatrol the camp followers who are orgamzing the Union League. They live a charmed 1ife.” hat night, es ‘he preacher walked from a visit to a destizute family icountered a burly negro on the side- k, dressed ‘n an cld sult of Fcderal niform, evidently under the in‘luence of whisky. He wore a belt around his waist, which he had thrust, conspiculcu an old horse pistol. Standing squarely across the pathway, he id to the preacher: 3t outer de road, white man; you'se er rebel, I'se er Loyai Union Leag: It was his first experience with negro insolence since the emancipation of his slaves. Quick as a flash, his right arm as raised. But he took a second thought epped aside and allowed the drunk He went home wondering v sort of way through his ex- cited passions what the end of It all wouid be. Gradually in his mind for days this towering figure of the free had been growing more and mor ous, until its menace oversh erty, the hunger, the sorrow f th uth, throwing the t of its sha over future genera- able black dea the | ng CHAPTER IV. LINCOLN'S DREAM ng_before the s br st callers were g at the & negro, the poor widow, the orphan, the wound: rocession. MR preacher h it terrible army of of whose been paral- scene of peaceful has no pit dark ore the people of the Sou 1 us of the Ang s had sudde dations of ecor ve billions of dollars’ v were wiped 4, every d th the flower of nameless P ly and earnestly t South set about this his proclamation f restoring the 1 to him from . and indi abinet. en sacrificed of Nortk good faith y eleot, composed of the noblest and chose an old 1 = who of ed the ma and organizer ition ich dest =0 drama abo League, tragic a part in the low, was Hogg, was forceful sty 2 virulent justified and eld slavery, and had written a e of poems dedicated to John ed the moverme convention his ship ck upon ofessed the sentiments, wormed into the confiuence .. .¢ Fed- ernment and actually svoceeded g the Provisional of the Btate! He loudly pro- his loyvalty and with fury and - demanded that Vance, the great war Governor, his predecessor, who as Ur man had opposed secession, should be hanged, and with him his own former associates in the Secession Con- ion, whom he had misled with his eral Go But the peeple had a long memory. They saw through this hollow preten: grieved for thelr great leader, who was now Jocked In a prison cell in Washing- ton, &nd voted for’ Andrew Macon. In the bitterness of defeat, Amos Hozg rpened his wits and his pen, and be- gan his schemes of revengeful ambition The fires of passion burned now in tha hearts of hosts of cowards, North and foe in bat- Thelr day had come. The .ames were the vengn and their The preacher threw the full weight cf his character and influence to defeat Hogg, and he succeeded In carrying the county for Macon by an overwheiming majority. At the election only the men who had voted under the old regime were allowed to vote. The preacher had not appeared on the hustings as & speaker, but es en organizer and leader of opinion he was easily the most powerful man in the county, and one of the most powertul in the State. CHAPTER V. THE OLD AND THE NEW CHURCH. In the village of Hambright the church was the center of gravity of the life of the people. There were but two churches the Baptist and the Methodist. The Ep! copalians had & bullding, but it was bullt by the generosity of one of their dead members. There were four Presbyterian families in town, and they were working desperately to bulld a church. The Bap- tists _had really taken the county, and the Methodists were their only rivals. Baptists had fifteen flourishing churches in the county, the Methodists #ix. There were no others. The meetings the village of Hambright were the most important gatherings in the county. On day mornings everybody who could walk, young or old, saint and sinner, went to church, and by far the larger number to_the Baptist church. You could tell by the stroke of the bells that the two were rivals. The sextons #cquired a peculiar skill in ringing these bells with a enap and a jerk that smashed the clapper against the side in a stroke that spoke deflance to all rival bells, Wwarning of everlasting fire to all sinners that should stay away, and due notice to the saints that even an apostle might be- Come & castaway unless he made haste. The men occupled bne side of t the Baptist church in THE FfFUNDAY CALL. n on the other. companying their mothers were to be seen on the woman's side, logether with a few young men who fearlessly escorted thither their sweet- P iafore the services began, between the ringing of the first and second bells, the men gathered in groups in the church- vard and discussed grave questions of politics and weather. The services over, the men lingered in the yard to shake hands with neighbors, praise or criticize the sermon, and once more discuss great ents. The boys gathered in quiet, wist- il groups and watched ghe girls come slowly out of the other door, and now and then a daring youngster summoned courage to ask to see one of them home. The services were of the simplest kind. The singing of the old hymns of Zion, the reading of the Bible, the prayer, the collection, the sermon, the benediction. The preacher never touched on politics, no matter what the event under whose world import his people gathered. War was declared, and fought for four terri- ble years. Lee surrendered, the slaves were frecd and soclety was torn from the foundations of centuries, but you would never have known it from the Y({\S of the Rev. John Durham in his pulpit. These .hings were but passing events, 1en he ascended the pulpit he was the senger of eternity. e spoke of God, uth, of righteousness, of judgment, e same yesterday, to-day and forever. Only in his prayers did he come closer to the Inner thoughts and perplexities of daily life of the people. He was a emarkable power in the pulplt. ¥ of the Bible was profound. d speak pages of direct discourse 1 its very language. To him it was a alphabet from whose letters he could compose the most impassioned mes- sage to the individual hearer before him. literature, its poetic fire, the epic sweep of the 1d Testament rec- ord of Jife, were Inwrought into the very fiber of his soul. As a preacher he spoke with authority. He was narrow and dogmatic in his in- terpretations of the Bible, but his very narrowness and dogmatism were of his flesh and blood, elements of his power. er stooped to controversy. He sim- iced the truth. The wise re- he fools rejected it and were That was all there was to it. But it was in his public prayers that h at his best. Here all the wealth erness of a great soul was laid In these prayers he had the subtle nius that could find the way direct into arts of the people before him, real- s his own their sins and sorrows, burdens and hopes &nd dreams and . and then, when he had made them could give them the wings of words and carry them up to art of God. He prayed in a low tone of volce; it was like an honest, st child pleading with his father. a hush fell on the people when prayers began! With what breath- suspense every earnest soul followed Before and during the war the gallery church, which was built and re- for the negroes. was always ed with dusky listeners that hung spellbound on his words. Now there were only a few, perhaps a dozen, and they were growing fewer. Some new and mys- terious power was at work among the negroes, sowing the seeds of distrust and suspicion. He wondered what it could be. He had always loved to preach to these simple-hearted children of nature, and watch the flash of resistless emotion weep their dark faces. ver five lowship He had baptized hundred of them into the fel- of the churches in the village county during the ten years of He determined to find out the cause of this desertion of his church by the ne- groes to whom he had ministered so many At the close of a Sunday morning’s ser- S as slowly descending the gal- y irs, leading Charlie Gaston by the , after the church had been nearly emptied of the white people. The preach- him near the door. s our mistress, Nelse?” s gettin’ better all de time now de Lawd Eve she stay wid er dis mornin' while I fetch dis boy ter church. He des so sot on goin'.” “Where are all the other folks to fill that gallery, Nelse?"” doan tell me you ain’t heard about he answered with a grin. I haven't heard, and I want to who laws-a-massy, dey done got er church er dey own! Dey has meetin’ now in de schoolhouse dat Yankee ’‘oman built. De teachers tell ‘em ef dey ain't good ernuf ter set wid de white folks in dere chu'ch, dey _got ter hole up dey haids and not 'low nobody ter push ‘em up in er nigger gallery. «So dey’'s got ole Uncle Josh Miller to preach fur ’em. He 'low he got er call, en he stan' up dar en holer fur ‘em 'bout er hour ev'ry Sunday mawnin' en night. En sech whoopin’, en yellln’, en bawlin'! Yer can hear ‘em er mile. Dey tries ter git me ter go. I tell 'em Marse John Durham's preachin's good ernuf fur me, gall'ry er no gall'ry. 1 tell em dat 1 spec er gal- I'ry nigher heaven den de lower flo’ eny- how—en fuddermo’, dat when I goes ter church T wants ter hear sumfin’ mo’ dan er ole fool nigger er bawlin’. I can holler myself. En dey low I gwine back on my color. En den I tell ‘em I spec I ain't 80 proud dat I can’t larn fum white folks. En dey say dey gwine ter lay fur me yit.” “I'm sorry to hear th sald the preacher thoughtfull. s . hits des lak T tell yer. T spec dey gone fur good. Niggers ain't got no sense nohow. I des wish 1 own ’'em erbout er week! Dey gitten madder'n madder et me all de time case I stay at de ole place en wuk fer my po’ sick mis- tus. Dey sen’ er kermitfee ter see me mos’ ev'ry day ter ‘splain ter me I'se free, De las’ time dey come I lam one on de haid wid er stick er wood erfo dey leave me _lone.” You must be careful, Nelse.” ““Yassir, I nebber hurt 'im. Des sorter crack his skull er little show 'im what 1 gwine do wid 'im nex' time dey come pesterin’ me.” “Have they been back since?” “Dat dey ain't. But dey sont me word dey gwine git de Freeman's Buro atter me En I sont 'em back word ter sen’ Buro right on en I land 'im in de middle er a spell er sickness des es sho’ es de Lawd gimmg strenk.” ““You can’t resist the Freedman's Bu- reau, Nelse.” “What dat buro got ter do wid me, Marse John?" “They've got everything to do with you, my boy. They have absolute power over all questions between the negro and the white man. They can prohibit you from working for a white person without their consent, and they can fix your wages and make your contracts.” W dey better lemme erlone, or dere’ll be trouble in dis town, sho’s my name's Nelse.” “Don’t you resist their officer. Come to me if you get into trouble with them,” was the preacher’s parting injunction. 2 e made his way out leading Charlle by the hand, and bowing his giant form in a quaint deferential way to the white people he knew. He seemed proud of his assoclation in the church with the whites, and the position of Inferiority assigned im in no sense disturbed his pride. He was muttering to himself as he walked slowly along looking down at the ground thoughtfully. There was infinite scorn and deflance in his voice. “Bu-ro! Bu-ro! Des let 'em fool wid me! I'll make 'em see de seben stars in de middle er de day. to see you CHAPTER VL THE PREACHER AND THE WOMAN OF BOSTON. The next day the preacher had a call from Miss Susan alker of Boston, whose liberality had built the new negro schoolhouse and whose life and fortune were devoted to the education and eleva- tion of the negro race. She had been in the village often within the year, run- ning up from Independence, where she was bullding and endowing a magnificent classical college for negroes. He had oft- eh neard of her, but as she stopped with negroes when on her visits he had never met her. He was especially interested in her after hearing incidentally that she was a member of a Baptist church in Boston. On entering the parlor the preacher greeted his visitor with the deference the typical Southern man instinctively pays to woman. % “I am pleased to meet you, madam, he sald\with & gracefal bow and kindiy smile, as he led her to the most comforta- ble seat he could find. She looked him squarely in the face for a moment as though surprised and smil- ingly replied: “I belleve you Southern men are all alike, woman flatterers. You have a way of making every woman believe you think her a queen. It pleases me, I can't help confessing it, though I sometimes despise myself for it. But I am not going to glve you an opportunity to feed my van- ity this morning. I've come for a plain face-to-face talk with you on the one sub- Ject that fills my heart, my work among the freedmen. You are a Baptist minis- ter. I have a right to your friendship and co-operation.” 7 A cloud overshadowed the preacher’s face as he seated himself. He eald noth- ing for a,moment, looking curiously and thoughtfully at his visitor. He seemed to be studying her character and to be puzzled by the problem. She was a woman of prepossessing appear- ance, well past 35, with streaks of gray appearing in her smoothly brushed black hair. She was dressed plainly In rich brown material cut in taflor fashion, and her heavy bair was drawn straight up pompadour style from her forehead with apparent carelessness and yet in & way that heightened the impression of strength and beauty in her face. Her nose was the one feature that gave warn- ing of trouble in an encounl:& She was plump in figure, almost sto and her nose seemed too small for the breadth of her face. It was broad enough, but too short, and was pug tipped slightly at the end. 'She fell just a little short of being handsome and this nose was responsible for the failure. It gave to her face when agltated, In spite of evident culture and refinement, the expression of a feminine bulldog. Her eyes were flashing now and her nos- trils opened a little wider and began to push the tip of her nose upward. At last she snapped out suddenly: Vell, which is it, friend ‘or foe? u honestly think of my work?" Pardon me, Miss Walker; I am not ac- customed to speak rudely to a lady. If I am honest, I don't know where to be- in.” \ ‘ > 5 Ban! Lay aside your Don Quixote Southern chivalry this morning and taik to me in plain English. It doesn’t matter whether I am a woman or a man. I am an idea, a divine mffssion this morning. I mean to establish a high school in this village for the negroes, and to build a Baptist church for them. I learn from them that they have great faith in you. Many of them desire your approval and co-operation. Will you help me?" To be perfectly frank, I will not. You ask me for plain English. I will give it to you. Your presence in this village as & missionary to the heathen is an insult to our intelligence and Christian man- hoo®. You come at this late day as a missionary among the heathen, the heath- en whose heart and brain created this republic with civil and religious liberty for its foundations, a missionary among the heathen who gave the world Wash- ington, whose giant personality three times ‘saved the cause of American lib- erty from ruin when his army had melted away. You are & missionary among the children of Washington, Jefferson, Mon- roe, Madison, Jackson, Clay and Calhoun! Madam, I have baptized into the fellow- ship of the church of Christ in this coun- ty more negroes than you ever saw in all your life before you left Boston. At the close of the war thers were thousands of negro members of white Baptist churches in the State. Your mis- sion is not to proclaim the gospel of Jesus Christ. Your mission s to teach crack- brained theories of social and political equality to four millions of ignorant ne- groes, some of whom are but fifty yedrs removed from the savagery of African jungles. Your work is to separate and alienate the negroes frum their former masters who can be thelr only real friends and guardians. Your work is to sow the dragon’s teeth of an impossible social order that will bring forth its har- vest of blood for our children.” He paused a moment and, suddenly fac- ing her, continued: *“I should like to help the cause you have at heart, and the most effective service I could render it now would be to box you up In a glass cage, such as are used for rattlesnakes, and ship vou back to Boston.” “Indeed! I suppose, then, It is still a crime In the South to teach the negro?” She asked this in little gasps of fury, her eyes flashing deflance and her two rows of white teeth uncovering by the rising of her pugnacious nose. 1\ “For you, yes. It is always a crime to teach a lle. ““Thank you. Your frankness is all one could wish!” “Pardon my apparent rudeness. You not only invited, you demanded it. While about it, let me make a clean breast of if. I do you personally the honor to ac- knowledge that you are honest and in dead earnest, and that you mean well. You are simply a fanatic.” “‘Allow me again to thank you for your candor!” “Don’t mention it, madam. .You will be canonized in due time. In the mean- time let us understand one anothe ur lives are now very far apart, though we read the same Bible, worship the same God and hold the same great faith. In the settlement of this negro_question you are an insolent -interloper. You're worse; you are a willful, spoiled child of rich and powerful parents playing with matches in a powder mill. 1 not only will not help you—I would, 1f I had the power, seize you and remove you to a place of safety. But I cannot oppose you. You are protected in your play by a mil- lion bayonets, and back of these bavo- nets are banked the fires of passion in the North ready to bursfiinto flame in a moment. The only thing I can do is to ignore your existence. You understand my position.” ““Certalnly, naturedly. She had recovered from the rush of her anger now and was herself again. A cu- rious emile played round her lips as she quietly added: “I must really thank you for your can- dor. You have helped me immensely. I understand the situation now perfectly. I shall go forward cheerfully in my work and never bother my brain again about you, or your people, or your point of view. You have aroused all the fighting blood in me. I feel toned up and ready for a life struggle. I assure you I shail cherish no {ll feeling toward you. I am only sorry to see a man of your powers 80 blinded by prejudice. I will simply ignore you.” ““Then, madam, it {s quite clear we agree upon establishing and malintaining a great mutual ignorance. Let us hope, paradoxical as it may seem, that it may be for the enlightenment of future gen- erations.” She arose to go, smiling at his speech. “‘Before we part, perhaps never to meet again, let me ask {ou one question,” sald ;he preacher, still looking thoughtfully at doctor,” she replied, good last er. “Certainly, as many as you like.” "“Why is it that you good people of the North are, spending your millions here now to help only the negroes, who feel least of all the sufferings of this war? The poor white people of the South are your own flesh and blood. These Scotch Covenanters are of the same Puritan stock; fese German, Huguenot and Eng- lish people are all your kinsmen, who stood at the stake of your fathers In the Old World. They are, many of _them, homeless, without clothes, sick and hun- gry and broken-hearted. But one in ten of them ever owned a slave. They had to fight this war because your armies in- vaded their soil. But for thelr sorrows, sufferings and burdens you have no ear to hear and no heart to pity. This is a strange thing to me.” “The white people of the South can take care of themselves. If they suffer, it is God's just punishment for their sins in owning slaves and fighting against the flag. Do I make myself clear?”’ she snap- pe rfectly; I haven't another word to "My heart yearns for the poor dear black people who have suffered so many years in slavery and have been denled the rights of human beings. I am not only going to establish schools and col- leggs for them here, but I am conduct- ing’ an experiment of thrilling interest to me which will prove that their intellec- tual, moral and social capacity is equal to any white man’ = Is 1t 80?” asked the preacher. “Yes, I am collecting from every sec- tion of the South the most fromlsln! specimens of negro boys and sending them to our t Northern universities, where they will be educated among men who treat them as equals, and I expect from the boys reared in this atmosphere men of transcendent genius, whose bril- liant achlevements in science, art and let- ters will forever silence the tongues of slander against their race. The most in- teresting of these students 1 have at Harvard now {s young George Harris. His mother {s Eliza Harris, the history of whose escape over the ice of the Ohio River ‘fleeing from slavery thrilled the world. This boy is a genius, and if he lives he will shake this nation,” “It may be, Miss Walker. There are more ways than one to shake a natlon. And while I ignore your work, as a cit! Zen and publle manoprivately &nd per- sonally, watch this experiment with profound interest.” ‘I know it will succeed. I believe God made us of one blood,” she sald with en- thusiasm. “Is it true, madam, that you once en- dowed a home for homeless cats befors you became lmewtod in the black peo- ple?” With a twinkle in his eye, the preacher softly asked this apparently ir- relevant question. “‘Yes, sir; I did—I am proud of it. I love cats. There are over a thousand in the home now and they are well cared for. Whose business is 1t?"” “I meant no offense by the question. I love cats, too. But I wondered if you were collecting negroes only now, or Wwhether you were adding other specimens to your menagerie for experimental pur- poses.” She bit her lips, and In spite of her ef- forts to restrain her anger tears sprang to her eves as she turned toward the preacher whose face now looked calmly down upon her with ill-concealed pride. ‘Oh! the insolence of you Southern peo- ple toward those who dare to differ with you about the negro!” she cried with rage. “I confess it humbly as a Christian, it is true. My scorn for these maudlin {deas is so deep’that words have no power to convey it. But come,” said the preacher in the kindliest tone; “enough of this. I am pained to see tears in your eyes. Par- don my thoughtlessness. Let us forget now for a little while that you are an idea, and remember only that you are a charming Boston woman of the house- hold of our own faith. Let me call Mrs. Durham, and have you know her and dis- cuss with her the thousand and one things dear to all women's hearts.”” “No; I thank you. I feel a little sore end brulsed, and social amenities can have no meaning for those whose souls are on fire with such antagonistic ideas yours and mine. If Mrs. Durham can give me any sympathy in my work I'll be delighted to see her; otherwise I musy o The preacher laughed aloud. “Then let me beg of you never meet Mrs. Durham. If you do, the war will break out again. I don’t wish to figure in a case of mssault and battery. Mrs, Durham was the owner of fifty slaves. She represents the bluest of the blue blood of the slave-holding aristocracy of the South. She has never surrendered and she never will. Wars, surrenders, constitutfonal amendments’ and such little things make no impression on her mind whatever. If you think I am diffi- cuit, you had better not puzzle your brain over her. 1am a mildly constructi of progress. She is a conservativ “Then we will say good-by,” said Miss ‘Walker, extending her small plump hand in friendly parting. “I accept your chal- lenge which this interview impiles. I will succeed if God lives,” and she set her lips with a snap that spoke volumes. “And I will watch you from afar with sorrow and fear and trembling,” respond- ed the preagher. CHAPTER VIIL THE HEART OF A CHILD. Mrs. Gaston's recovery from the brain fever which followed her prostration was slow and painful. For days she would be quite herself as she would sit up in bed and smile at the wistful face of the boy who sat tenderly gazing into her eyes, or with swift feet was running to do her slightest wish, Then days of relapse ‘would follow, when the ‘child's heart would ache an ache with a dumb sense of despair as he listened to her incoherent talk and heard her meaningless laughter. When at length he could endure it no longer, he would call Aunt Eve, run from the house as fast as his little legs could carry him, and in the woods lie down In the shadows and cry for hours, “I wonder if God is dead?” he sald one day, as he lay and gazed at the clouds sweeping past the openings {n the green foliage above. ¥ “I pray every day and every night, but +she doesn’t get weil. Why does he leave her like that, when she's so good!" and then his voice choked into sobs, and he buriea his face in the leaves. He was suddenly roused by the voice of Nelse, who stood looking down on his forlorn figure with tenderness. “What you doin' out in dese woods, honey You'se er crying ’be ' L rying 'bout yo' The boy nodded without looking up. “Doan do dat way, honey. You'se tno little ter cry lak dat. Yer Ma's gittin® better ev'ry day, de doctor done tole mes so0. “Do you think so, Nelse?” There was an eagerness and yearning in the child's voice that would have moved the heart of a stone. “Cose I does. She be strong en well in little while when cole wedder comes. Fros' ‘1l soon be here. I see whar er ole rabbit been er eatin’ on my turnip tops. Dat's er sho sign. I gwine make you er rabbit box termorrer ter ketch dat rabbit.” “Will you, Nelse?" “'Sho’s you bawn. Now des lemme pick you er chune on dis banjer 'fo I goes ter my wuk.”" Of all the music he had ever heard the boy thought Nelse's banjo was the sweat- est. He accompanied the music in a deep bass volce which he kept soft and sooth- ing. The boy sat entranced. With wide cpen eyes and half-parted lips he dreamed his mother was well, and then that he had grown to be a man, a great man, rich and powerful. Now he was the Governor of the State, living In the Governar's pal- nce, and his mother was presiding at a banquet in his honor. He was bending proudly over her and whispering to her that she was the most beautiful mother in the world. And he could hear her say with a smile: ““You dear boy!" Suddenly the banjo stopped, and Nelse ralled with mock severity, “Now look at 'im er dryin’ ergin, en me er pickin' de eens er my fingers off fur 'im “No, I aln't cryin’. I am just listenin’ to the music. Nelse, you're the greatest jo player in the world!” “‘Na, honey, hits de banjer, Dats de Jo- blofnest banjer! En des ter t'Ink—er Yan- kee gin 'er to me In de wah! Dat wuz the fus’ Yankee I ebber seed had sense ernuf ter own er banjer. I kinder hate ter fight dem Yankees atter dat.” “But Nelse, if J00 vere fighting with cur men, how did you gethciose to any Yankees?'" “Lawd, child, we’'s allers slippin’ out twixt de lines atter night er carryin’ on fdm gn.nxm. We tudlo ‘em terbac cer fur coffee en sugar, en play fi{ll‘d en talk twell mos’ day sometime. I slip out fust in er patch er woods twix’ de lines, en make my banjer talk. En den yere dey come! De Yankees fum one way en our boys de yudder. I make out lak I doan see 'em tall, des playin' ter myself. Den I make dat banjer moan en cry en talk about de folks way down in Dixie. De boys creep up closer en closer twell dey right at my elbow en I see 'em cryin’, some un 'em—den I gin 'er a juk! en way she go pluckety plunck; en dey gin ter dance and laugh! Somefime dey cuss me lak dey hit me hard on de back. When lak dey xfing en lam me on de back. When gimme all dey got.” “But how did you get this banjo, Nelse?” “Yankee gin ‘er ter me one night ter try ‘er, en when he hear me des fairly pull de insides outen 'er, he "low dat hit "ed be er sin ter ebber sep'rate us. Ba)"' he neb- ber know what 'uz in er banjer. else rose to go. “Now, honey, doan you no mo, en I make you dat rabbit box sho’ en erlong 'bout Chris'mas I gwine larn you how ter shoot."” ia “Will you let me hold the gun?’ the boy eagerly asked. I des sho you how ter poke yo gun in de ‘crack er de fence en whisper ter de trigger. Den look out birds en rabbits! The boy's face was one great smile. It was late in September befors his mother was strong enough to venturs out of the house—six terrible months from the day she was stricken. What an age it seemed to a sensitive boy's soul. To him the days were weeks, the weeks months, the months long weary years. It seemed to him he had lived a lifetime, died and was born again the day he saw her first walking on the soft grass that grew under the big trees at the back of the house. He was gently holding her by the hand. “Now, mama dear, sit hers on this seat; you mustn't get in the sun. “But, Charlle, I want to see the flowers on the front lawn.” i “No, no, mama; the sun {s shinin’ awful on that s{de of the house! A great fear caught the boy’s heart. The lawn had grown up a mass of weeds and grass during the long hot summer and he was afrald his mother would cry when she saw the ruin of those flowers she loved so well. How impossible-for his child’s mind to foresee the gathering black hurricane of tragedy and ruin soon to burst over that lawn. Skillfully and firmly he kept her on ths seat In the rear where she could not see the lawn. He said everything he could think of to please her. She would smile and kiss him in her old sweet way until his heart was full to bursting. “Do you remember, mama, how many times when you were so sick 1 used to up close and kiss your mouth and eyes?.’ “ often dreamed you were kissing me. “I thought you would know. I'll soon be a man. I'm going to be rich. and build a great house and you are going to liye in it with me, and I am to take care of you as long as you live.” “I expect you will marry some pretty girl, and almost forget your old mama who will be getting gray “But I'll never love anybody like I love you, mama dear.” His little arms slipped around her neck, held her close for a moment and then he tenderly kissed her. After supper he sought Nelse. “Nelse, we must work out the flowers in the lawn. Mama wants to see them. It was all I could do to keep her from go- ing out there to-day.” “Lawd, chile; hit'll take two niggers er weel to clean out dat lawn. Hit's gone fur dis year. Yer ma’ll know dat, honey.” The next morning after breakfast the boy found a hoe, and in the plercing sun began manfully to work at those flowers. He had worked perhaps a half hour. His face was red with heat and wet with sweat. He was tired already and seemed to make no impression on the wilderness of weeds and grass. Suddenly he looked up and saw his mother smiling_at him. “Come here, Charlie!” she called. He dropped his hoe and hurried to her side. She caught him in her'arms and kissed the sweat drops from his eyes and mouth. “You are world!" What music to his soul these words to the last day of his life! “I was afrald when vou saw all these weeds vou would cry about your flowers, . ¥ the sweetest boy In the ma. ““It does hurt me, dear, to see them, but it's worth all their loss to see you out there In the broiling sun working 50 hard to please me. I've seen the most beautiful flower this morning that ever blossomed on my lawni—and its perfume will make sweet my whole life. T am going to be brave and live for you now.” And she kissed him fondly again. CHAPTER VIIL AN EXPERIMENT IN MATRIMONY. Nelse was Informed by the agent of the Freedman's Bureau when summoned be- fore that tribunal that he must pay a fee of one dollar for a marriage license and be married over again. “What's dat? Dis yer war bust up me en Eve's marryin'?” “Yes,” said the agent; legally married.” Nelse chucked on a brilllant that flashed through his mind. “Den I see you ergin 'bout dat,” sald, as he hastily took his leave. He made his way homeward revolving his brilliant scheme. “But won't I fetch dat nigger Eve down er peg er two! I gwine ter make her t'ink I won't marry her nohow. I make ’er ax my pardon fur all dem little disergreements. She got ter talk mighty putty now, sho’ nuf!” And he smiled over his coming triumph. It was 4 o'clock in the afternoon when he reached his cabin door on the lot back of Mrs. Gaston's home. Eve was busy mending some clothes for thelr little boy now nearly five years old ““Good evenin’, Miss Eve!" Eve looked up at him with a sudden flagsh of her eye. ‘What de matter wid you, nigger?” Nuttin' ‘tall. Des drapped in lak ter pass de time er day, en ax how’s you en yer son standin’ dis hot wedder.” Nelse bowed and smiled. ‘““What all you, you big black baboon?" “Nuttin® *tall, m'am; des callin’ 'roun’ ter see my frien's."” St smliling, Nelse walked in and sat down. Eve put down her sewing, stood up be- fore him, her arms akimbo, and gazed at him steadily till the whites of her eyes began to shine likp two moons. “Yer wants me ter whale you cber de head wid dat poker? “Not dis evenin’, m'am.” “Den what afls you?” “De buro des inform me dat es I'se er young, han'some man, en you'se er git- tin’ kinder ole en fat, dat we ain’t mar- ried nohow. En dey gimme er paper fur er dollar dat allow me ter marry de young lady er my choice. Dat sho' is er great buro!" “We ain’t married?” sy Nob-um. tter stan’ up dar befo’ Marse John Durham en say des what all dem white folkd say?” “Nob-um."” Eve slowly took her seat and gazed down the road thoughtfully. “I t'ink I drap eroun’ ter see you en gin you er chance wid de odder gals fo’ T steps off.”” explained Nelse with a grin, No answer. “You 'member dat night I say sumfin® *bout er gal I know once, en you riz en grab er poun’ er wool outen my head fo’ I kin move?” No answer yet. “Min’ dat time you bust de biscult bode ober my head, en lam me wid de fire shovel, en hit me. in de burr er de year wldrar flatiron es I wuz makin’ fur de ao'?" “Yas, T min's dat sho’!” sald Eve, with evident satisfaction. “Doan you wish you nebber done dat?” “You black debbil!” “Dat’s hit! I'se er bad nigger, m'am— bad nigger fo’ de r. En I'se gittin® ‘wuss en wuss,” Nelse chuckled. She looked at him with gathering rage and contem&g. “En den, fuddermo’, m'am, I doan lak de way you talk ter me sometimes. Yo’ “you must be scheme he voice des kinder takes de skin off same's er file. I laks ter hear er ‘oman's voice lak my<missy’'s, des es sof’ es wool. Sometime one word from her keep me warm all winter. De way you talk some- time make me cole in de summer time." Nelse rose, while Eve sat motionless. “I des call, m’am, ter drap er little int- ment inter dem years er yourn dat'll per- cerlate froo you' min’, en when I calls ergin I hopes ter be welcome wid smiles.” Nelse bowed himself out the door in grandiloquent style. All the afternoon he was laughing to himself over his triumph and imagining the welcome when he returned that even- with his marriage license and officer to perform the ceremony. At sup- per in the kitchen he was polite and for- mal in his manners to Eve. She eyed him in a contemptuous sort of way and never spoke unless it was absolutely nec- essary. It was about half past 8 when Nelse arrived at home with the license duly is- sued and the officer of the bureau ready to perform the ceremony. “Des walit er minute here at de corner, ah, till I kinder breaks de news to ‘em.’ said Nelse to the officer. He approached the cabin door and knock It was shut and fastened. He got no response. He knocked loudly again. Eve thrust her head out the window. Vho's dat?” “Hit's me, m'am, Mister Nelson Gas- ton; I'se call ter ses you.” “Den you hump yo'se’t en git away from dat do’, you rascal.” “De Lawd, honey; I'se des been sr fool- in' you ter day. I'se got dem licenses en de buro man right out dar now ready ter marry us. You know yo ole man nebber gwine back on you—I dés been er foolin’.” = ou been er foolin' wid de wrong “Lawd, honey, doan keep de bridegroom er waitin.” “Git er way from dat do'l" “G’long, chile, en quit yer Nelse was using his softest an suasive tones now. “G'way from dat do'!" “Come on, Eve; de man waitin’ out dar tur us!” “Git away, I tells you, wid er kittle er hot water!' Nelse drew back slightly from the door. “But, honey, whar you ole man gwine ter sleep?” “Dey’s straw in ters in de doghouse. ming the window. “Eve, honey!— “Doan you come honeyin’ me; I'se er ‘spec’able 'oman, I is. £ you wants ter marry me you got ter cothe co’tin’ me in de daytime fust, en bring me candy, en ribbins, en flowers and sich, en you got ter talk purtler'n you ebber talk in all yo born days. Lots er llkely lookin’ nig- gers come settin’ up ter me while you gone In dat wah, en I keep stud’in’ "bout you, you big black rascal. Now you got ter hump yo'se’f ef you eber see de inside er dis cabin ergin.” Crestfallen, Nelse returned to the offl- Jeckin’."” most per- I scald you barn en pine shat- * she shouted, slam- deys er kinder hitch in de hat’s the matter?” “She 'low I got ter come co'tin’ her fust. En I spec I 1s." The officer laughed and returned to his home. She made- Nelse sleep in the barn for three weeks, court her an hour every day and bring her 5 cents’ worth of red sfck candy and a bouquet of flowers as a peace offering at every visit, Finally she made him write her a note and ask her to take a ride with him. Nelse got Charlie to write it for him and made his own boy carry it to his mother. After thres weeks of humility and attention to her wishes, she gave her consent, and they were duly married again. CHAPTER IX. A MASTER OF MEN. The first Monday in October was court day at Hambright, and from every nook and corner of Campbell County the peo- ple flocked to town. The courthouse had not yet been transformed into the farce- tragedy hall where jailbirds and drunken loafers were soon to sit on Judge's bench and in attorney’s chair instead of stand- ing in the prisoner's dock. The mereiful stay laws enacted by the Legislature had silenced the cry of the auctioneer until the people might have a moment to gird themselves for a new life struggle. But the black cloud was already see on the horizon. The people were res less and discouraged by the wild rumors set afloat by the Freedman's Bureau, of coming gonfiscation, revolution and re- venge. A greater crowd than usual had come to town on the first day. The streets were black with negroes. A shout was heard from the crowd in the square, as the stalwart figure of Gen- eral Danfel Worth, the brigade comman- der of Colonel Gaston's regiment, was seen shaking hands with the men of his old_army. The general was a man to command instant attentlon in any crowd. An ex- pert in anthropology wou'd have selected his face from among a tiousand as the typical man of the Caucaslan race. H was abovy the average helght, a strjng, muscular and well rounded bedy, crowned by a heavy shock of wha' had once been raven black hair, now iron gray. His face was ruddy with the glow of perfect health and his full round lips and the twinkle of his eye showed him to be a lover of the good things of life. He wore a heavy mustache which seemed a fit- ting ballast for the lower part of his face against the heavy projecting straight eye- brows and bushy hair. As he shook hands with his old soldiers his face was wreathed in smiles, his ey flashed with something iike tears and bad a pleasant word for all. Tom Camp was one of the first to spy the general and hobble to him as fast as his pegleg would carry him. “Howdy, general; howdy do! Lordy, it's good for sore eyes ter see ye.” Tom held fast to his hand and turning to the crowd said: “‘Boys, here's the best general that ever led a brigade, and there wasn't a man in it that wouldn’t a dled for htm. Now three times three cheers!” And they gave it with a will. “Ah! Tom, you'rs still at your old tricks,” said the general. ‘“What are you after now?"” “A speech, general”—“A speech! A speech!” the crowd echoed. The general slapped Tom om the back and sald: ““What sort of a job is this you're put- ting up on me; I'm no orator! But I'll just say to you, boys, that this old peg- leg hers was the finest soldler that I ever saw carry a musket, and the men who stood beside him were the most patient, the most obedient, the bravest men that ever charged a foe and crowned thelr gen- eral with glory while he safely stood in the rear.” Again a cheer broke forth. The gen- eral was hurrying toward the courthouse, when he was suddenly surrounded by a crowd of negroee. In the front ranks were a hundred of his old slaves who had worked on his Campbell County plan- tation. They seized his hands and laughed and cried and pleaded for recognition like a crowd of children. Most of them he knew. Some of their faces he had for- gotten. “Hl dar, Marse Dan’l; you knows me! Lordy, I'se your boy Joe dat used ter ketch yo hoss down at the plantation!™ “Of course. Joe! Of course.” “I know Marse Dan'l ain’t forgot old Uncle Rube,” said an aged negro, push- ing his wav to the fromt. “That I haven't, Reuben; and how's Aunt Julle Ann?” 3 “She des tollable, Marse Dan’l.’ We'se bof un us had dsT?lumbl(o. How is you all sence de wah?" “‘Oh, first rate, Reuben. We m: somehow to get enough to eat, and if wi do_that nowadays we can’t complain “Dat’s de God’s truf, marster, sho'l En now Marse Dan’l, we all wants you ter make us er speech en ’splain erbout dis freedom ter us. Dey’s so many dese yere buroers en leaguers 'round here tellin’ us niggers what's er comin’, twell wa des doan know nuttin’ fur sho’.” "Ylllg; dll:t”l hit! You tell us er speech, n’