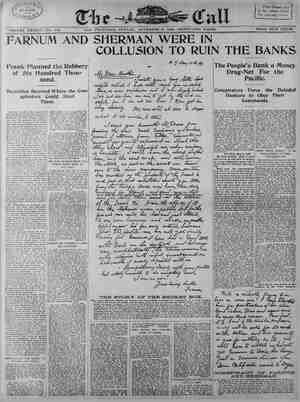

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 6, 1898, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

“The layman has no rights of citizenship which should be denied the priest.”’— “I think politics are in the hands of the people, out of the hands of the priests.”’— Mr. Phelan’s office in the Phelan building i{s guarded without and within. The elevator man was sure Mr. Phelan had just gone out. The clerk in his reception office was not sure that he would ever return. I suggested that he might come back to an appointment with me and the clerk admitted me without & blush into the Hon- orable presence. > “This is very nice and hospitable of you,” I said, entering mod- estly. “Is this your studio?” ‘“What?"” sald the Mayor. I waved around at the canvases on the walls, the brasses, bronzes, marbles, portieres, pedestals, deep-hearted divans, sumptu- ous chalrs, the carpets of the Orient, the screens of Japan, the carved woods of Venice, the objets d’'art of everywhere. “You ought to have on a velvet jacket and a beret,” sald I, “and offer tc make me some tea.” “A beret!” said the Mayor, laughing. ‘‘Another hat?” “I never objected to your hats! It was your campaign coat I aidn’t care for. You do not wear it mornings, do you?” And indeed the Mayor looked very tidy in another cut of coat entirely and a swell dark tie pinned with the modest pearl and his neat hair neatly brushed and his neat beard neatly trimmed and his whole small self.polished and groomed with that obvious careful ¢are which is one of the characteristics of his person. But he looked very weary—troubled, uncertain, a trifle less confident than of the recent yore—a trifle less cock sure of being Mayor for the next term over the head of Mr. Patton, the tongue and teeth of Father Yorke, the hide, hoofs, trunk and tail of the Grand Old Party. “I hope you will,” I sald suddenly. “Will what?" “Oh! Be the next Mayor." “Tranks!"” he answered smiling. peated, “will shake. of course once I took it up I Intended to see the end of it.” ‘Naturally. And how do you feel about the end of it now?” How do you mean that?” “Do you feel confident of winning it out now?” [/As much now as at any time. Why not?” “Father Yorke.” The Mayor shifted a little in his chair. has nothing to do with it.” “'You think his opinion will not influence the Catholic vote?” found the Mayor truthful since he was a little boy. “I do not wish t “Forgive me.” e “You can say,” sald the Mayor, “that you sought this inter Fwiitb /No, thanks. I don’t make a point of humliiity, you know."” “Yes, but I didn’t invite you to interview me.” “No. Still you seemed pleased to see me.” “Certainly! Certainly I was,” replied the Mayor. Put it any way you like! Only say that I would not talk.” “Heaven! I can’t make an iInteresting story out of that. T //// all this other little subsidiar~ conversation of ours. something about you—you are so Interesting just now.” “Thanks,” sald the Mayor, “anything you like! Father Yorke. Remember I refused to discuss the matter. 1 saic “I telleve our politics are the distinctly that it was a controversy which involved no principle.”’ “I beg your pardon?” “Certainly. Yes, I hope you will be elected.” “That’s very good of you, I'm sure. Because I'm a Democrat?” citizen?” “Not as a criticism on Father Yorke, but as-a general-prineiple?’ “As the personal opinion of a practical politician?' ‘ > “Yes. No, because you have a taste in art. So few Mayors have, “I think that politics are in the hands of the peo- you know. There have been only you and Mr. Sutro—* ple and out of the hands of the priests.” 7 “AhL?” interrupted the Mayor coldly. “And that the people will vote themselves J/ “—and you reelly care for it, don't you? The improvement of away?" 1% /I/ /) “Father Yorke himself says they will.” . “Tell m priest?” said the Mayor, “am a good Catholic.” R R e AT e the , I mean.” i “That reminds me, I must write to Douglas Tilden about that fountain!" Th2 Mayor reached out his hand and scribbled a memorandum across the top of a pamphlet lying on his desk. I read the title of the pamphlet—'Father Yorke to James D. Phelan.” Beslde it lay another—“Father Yorke to James G. Maguire.” “Of course, the duties of a Mayor are not entirely architectural,” I went on thoughtfully, “but it is very nice when He can combine say—architecture and honesty. I really think you are honest, too.” “Do you?” replied the Mayor. “So do 1" “I intend to say so when I write this interview.” “Ha! ha!” said the Mayor. ‘“You won't be allowed to, you know.” “No, T don’t know at all.” “What! For The Call?” “Certainly. You don't appreciate The Call, perhaps.” “Perhaps not,” said the Mayor, looking pensively at his hat. ‘But don’t you think that feeling is mutual?" “How about this feeling?” I leaned over and touched the pamph- let with the title “Father Yorke to James D. Phelan” and the memo- randum about writing to Douglas Tilden across the top. 0!” said the Mayor, foxily. *“So that is it—is 1t?" t else would it be at this hour? Is the town talking about nything else?” “Well, I am not talking on that subject,” sald the Mayor, shutting his 1i together, “Positively not?” “Positively not. “Qh, very well.” “Father Yorke has chosen to accuse me of dishonesty and a few other little crimes against my office and against the people who put me in office. I have nothing to say in reply. Absolutely nothing.” “Oh, very well.” “Of course he claims that it is because I support the nomination of Clinton, Lackmann and Dodge. In this Sailors’ Home matter he ‘laims that they voted against the policy of the institution, which was nom-gectarian, 1 have nothing to say on the subject, nothing.” “You will not discuss it at all?” “I will not.” “Not with any paper?” “Not even with any person. Why should I? Why should I be drawn into a controversy which involves no principle? Father Yorke has risen and made these accusations. He claims that he can prove them. Very welll I do not intend to enter into any personal argu- ment with Father Yorke as to whether or not I am worthy an 7 I said again. “Father Yorke is a / A tall, falr man, {n the dress of the priest, rose from the editor’s chair in the Monitor office and measured my coming with a broad, full, limpid, blue gaze. “I am Father Yorke.” Now may the devil fly away with the preconceived idea, and the foregone con- clusion go after them both! I have read Father Yorke’s contin- uous argument intermittently, illus- trating it with mind pictures of this nineteenth century crusader, this; scribbling soldier priest, this man J; alternately fed and eaten by an idea, this greatest space writer of the century. g I sketched him boldly—a gaunt form, and a flery eye, a lean jaw and a sallow cheek, a bi. man fierce yet cold, a priest passionate yet holy. “I am Father Yorke.” And he looks like a fine, overlarge, manly, promising boy baby— with a pink and white prettiness of skin a maid might sigh for, nursgery, a fair and youthful nose, a sweet, sensitive, humorous mouth, a smooth, white throat and a white, smoath hand with dimpled fingers. The chin tells the story. It is strong, combative, pratised and secure. And when a chin tells as much as that there is more behind it. “D3 you come,” asked the priest, “in a spirit of hostility?”” And I saw the challenge written on the chin. “No,” I answered truthfully, “I come in the spirit of curiost: “Ah?” he said easily. “Ah, and what were you curious about “You, Father.” Father Yorke showed his strong, regular teeth. “About me!” he said softly. “Did you think I was something out of the ordinary?" think so still.” . ecause I speak what I belleve to be the truth?” “Because you speak what you belleve to be the truth about political candidates on the eve of election and are not afraid of honor which already has been mine. My official record answers all consequences.” such questions. The people may decide for themselves on that point. “Afraid? Do you deny the priest cflirage as well as political I will not say one word about the matter.” opinions 2" “You do not think it i1s a personal matter with Father Yorke?" “Ah, Father! You must admit it was unprecedented.” “Personal, how? You mean a grudge of any sort? Not that I “Not at all! There has not been one vear in the history of the American Government when priest or bishop has not gone on record for plain speaking.” “In political affairs?” “In governmental affairs. We do not preach politics from the fulpit any more than we discuss politics at a gentleman’s dinner table—and for much the same reason. We have all denominations of politicians in the church—Republican, Democrat, Non-Partisan, So- clalist and, although I hope not, perhaps a few Anarchists. We do not interfere with their views. We do not offend their bellefs. It is the business of the moral teacher to uphold all the principles of good government. The American constitution has settled what those principles shall be. When one of those principles is attacked it is time the moral teaeher should interfere, If a man rises to abolish the commandment ‘Thou shalt not steal!” shall I not confront him and dispute him and prove him a bad man for the people—my peo- ple—all people. Catholic, Protestant, Jew or Gentile, to hearken to and to support? Shall I fear to speak lest people say I use the power of the.Catholic church as a lever in politics? Have I ever made my fight for equal rights a Catholic fight? If it were a Catholic fight could it be a question of equal rights? You have a principle. Do you pare it on this side and on that, like a pilece of cheese, to make it fit comfortably to circumstances? Not if you are an honest man. You strike at circumstance with your principle, you hack and hew circumstance, beat it aside, stamp on it, make a path through it and take your principle on to {ts goal. I am opposed—I have been opposed for five years—to men who deny the Catholic citizen equal rights with citizens of every other faith. I do not think the man who denies equal rights to all citizens, or who indorses the men who deny equal rights to all citizens, should have the suffrage of the people. I have said so hundreds of times before. They say I am a pugnaclous crank. They may be right there! But no man can say I have made fish of one and fowl of another. Many good Catholics are against me in this. They have my thanks. They stand to prove my assertion that the Catholic people are not ignorant, blind, priest-driven sheep, to follow as they are bid.” “Yet some will follow, I think, Father.” “I think so, too. I have said that James D. Phelan has been false to his friends, false to his promises, false ta his trust, false to himself. He says those are four lies by Father Yorke. There are some people who will take my word before his. They are those who look to me confidently for the truth as I see it—who feel with me that I owe it, a duty to them, to speak the truth as I believe it to be. But I deny that I have used the church to influence this following beyond the duty I owe as moral teacher to my children in the church. I speak to James D. Phelan to-day not as Father York}b:lt‘ the Roman Catholic priesthood, but as Peter C. Yorke, Amer} citizen.” 3 “Can you so separate yourself, Father, from your priesthood?” Father Yorke raised his smooth, white hands to heaven. “Why, why, why should I wish to do that? Is not a priest a man? You do not say to me, ‘Can you so separate yourself from your manhood as to become a priest? Are we In France or England, where the priesthood is a separate estate? We are in America, which does not excuse her clergy from the duties of citizenship. And I claim that in America the layman has no rights of citizenship which should be denied the priest.” i “Then you believe the priest may go into politics?” “Certainly—if_he has the mind.” 2 “What does the Archbishop think about it? know of.” The Mayor passed his hand a little wearily across his eyes. “I count his attack in as a part of the campaign. It is a long, hard fight, you know—" “I think it is beginning to tell on you,” I sald, looking him over criticaily. AF sl};ould think it might by this time,” sald the Mayor, fretfully. “It s not only the speeches, it is the whole thing; the vituperation, the mud slinging, the abuse, the newspaper abuse—you will excuse me for speaking so frankly?” “Oh, certainly, with all my heart. been doing it all.” “I really haven’t the time for it, either,” said the Mayor. “I am neglecting other interests—business interests.” He looked thought- fully at a bust of the late Phelan, his father—‘large business in- terests,” he resumed, slowly. “I have the welfare of the city very much at heart. I have tried, as you say, to improve {ts outward appearance as well as to assist in purifying its methods of govern- ment. I have fought the large corporations on principle. I stand with the people against the corporations.” “I rémember to have heard you say that in several of your speeches,” I remarked. *Yes,” replied the Mayor. “Doubtless. Of course, I have not had a sympathetic board to work with me. In this matter of im- proving the city I have had to fight, if not against the board at least without its co-operation. There is our present Supervisor of Streets—an excellent man, but afraid, you know, actually afraid! I want to go on with that work. There are those headless lamp posts— those horrors, those blots on the fair face of the city. I want those removed and I want to get all these unsightly wires down—way down underground, where they belong, out of the sight of man. I will have a hard tussle with the companies to whom they belong over that. They don’t want to put their wires underground. Why? Tt costs money! There yow are again—the greed of the corporation! The corporations are against the pecple and I am against the corporations. I think I have shown that in the last two years. And T think the people know that I have.” . e, “You certainly have many friends,” I said. Thne Mayor's weary face lightened and brightened with that sincere pleasure in being liked and admired and respected and ap- proved of and applauded and cheered for and brass-banded through the town which none who have seen him -mount the political plat- form can deny him or could disapprove. For why, say I, strugsgle for public honors unless the bay smells sweet? ‘Whosoever says to me he loves it not and then fights, bleeds, dies or does worse to wear it ‘or the good of his country and the benefit of his fellow man, I say o him go tell the tale to those credulous marines, who are trust- ‘ully disposed to believe everything they ear. The Mayor's imjle was good to see because it was sincere and smiled, so to speak, from the soul, and it crept up to his eyes and warmed them and rested on his.broad brow like a halo long after it had left his lips. He was saying to me— “Yes, I belleve I have—not only ‘shouth Market,’ where, I be- iieve, yott heard me speak, Lut wherever I speak, and especially among the householders, the smaller householders in the little resi- dence districts about the city. I belleve they feel confidence in my integrity and the sincerity of my purpose to protect their interests against the corporations, a confidence that nothing”—the Mayor ab- mently tapped the pamphlet under his fingers—"nothing,” he re- It isn’t as if my paper had FATHER YORKE. MAYOR PHELAN. I sometimes think,” he went on slowly, “that it was folly to have gone into this second term campaign fight, but “I think Father Yorke “I am not afraid of any man’s influence,” answered the Mayor— whether truthfully or not I cannot say, beyond that I have ever “AL! but the lnfl?nce of a priest is not the influence of any man!” discuss the subject,” said the Mayor, irritably. “Delighted have to describe your personal appearance and your furniture anc I 'must have Only not about same.”" “Tell me,” I said. “Leave Father Yorke out of the question and “Why, yes,” I replied, smiling back, “we only write for different take the thing in the abstract. Do you think the priest has a highe: papers.” sright to lead the people to the polls—as elsewhere—than the private mouth and a blue-black chin, a eyes of that pure, unshadowed, innocent blue that seldom leaves the | RS —_— |1‘h forn FT R L i ,”if‘ ;.il?!‘, 7, 7 “l (kivk his letter, which was practically an answer to the charges against me in the Bulletin, expresses his views. Not that it is likely to silence the Bulletin. ' That is perhaps too much to ex- pect fro:]n an Archbishop. There are some things the Lord himself cannot 0."" . He laughed ‘a big boyish laugh and sobered out of it suddenly. “I hope I may not be misconstrued,” he said, “with regard to Phelan or any other man. I arraign the official, or rather the man's . .Tontinued on Fage Twenty-siz