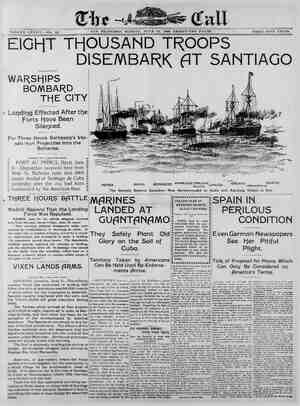

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 12, 1898, Page 20

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

20 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JUNE 12, 1898. « CUT CABLES WITH THE BULLETS RAINING ROUND THEM . Stories of the volunteers who ran right under the guns and over the mines of Cienfuegos and San Juan and cut the cables connecting Cuba with Spain. b /’ & = "BY WEST, Fla., June 9.—In the hospitals of Key West to- day I heard from lps that twitched with pain, while the eyes above them flashed with pride, simple stories told by the heroes of the war between the Uni- ted States and Spain—the common sailors who have given of their blood for their country. They made no boast of thelr valor; they made no complaint of thelr suf- fering; they grieved that they were wounded, but only because their com- panions, more fortunate than they when shot and shell were raining, had salled away in search of further glory and had left them helpless behind. Most of them are young fellows; all of them are above the average of in- telligence. They are the victims of their first experience in action; they told me it was target practice. In a stuffy ward at the barracks I found aefair, curly headed youngster who wrote his name for me, “H. Kush- meister, of New York,” and who, when I asked him what he was, said: “Oh, Jjust a marine—one of McCalla’'s of the Marblehead.” Men who care for detalls in history can well spare adjectives to praise him. He was one of those brave spirits who, in launches, protected only by their rifles and a small rapld firing gun whose supply of ammunition lasted W AR L — i DN \ 8 R \ \ only a few minutes, cut the cables at Cienfuegos in the faces of fifteen hun- dred Spaniards pouring bullets in streams from the Mausers. 2 A bullet entered his mouth and tore a terrible exit through his left cheek. He is up, however, and cheerful, though now and again the pain is so great that tears are forced from his eyes and the torture of talking is awful. “Yes,” he said, when I asked him to tell me about his experience, “they had us in a tough place, and if they had been any good we never would have got back to the Marblehead alive. We left the ship, some of us in a steam launch and others in a sailing launch. From the Nashville men were sent in the same fashion. “We were picked—that is, we were volunteers. I got into it because I have lots of medals as a marksman and wanted to show that I could hit Spaniards as well as targets. We went out to cut those cables under orders, and we did it—all but one, and that doesn’'t amount to anything, because it only runs to Santiago. Of cours we were under the guns of the cruiser and the gunboat, but, then, we ran in about forty feet from the shore, and could see the whiskers of the Spaniards once In a while before we got views of their retreating backs. But T guess T'll have to give it up now. This mouth of mine where the Mauser hit me is be- ginning to howl for me to stop. “How does it feel to be hit by a Mau- ser? I can't just tell you that, be- cause T don't know. T just didn’t have any head at all. You see, T was kneel- ing in the boat and taking aim. Oh, I had a beautiful bead on a Spaniard who showed above the bushes. The next thing I knew I had a sore face, and was on the Windom, being taken to Key West. Davis, I guess you'd bet- ter take up the story now. I'm done up on talk.” Davis had hobbled into the room on crutches while I was listening to his mate. He is known to his shipmates on the Marblehead as “Jock,” and is a gunner’s mate. His shore home is New York. He is sturdy, not more than 24 years old, and a splendid type of bright-eyed boyish-faced manhood, and is happy, although a builet ploughed a hole clear through his right leg below the knee. “Well, you s.e,” he began, “it was Just like this. Our captain, McCalla, said he wanted some men to go out in small boats and cut those cables, and I was in the bunch that wanted to go and take a shot or two to help get square fcr t.e Maine. Well, the captain that day he lined us up on deck and he says: *“ ‘Now, boys, I want you to know what you're doing. You ain’t going to no picnic. This isn’t a Sunday-school party, or an excursion, either. me of you may come back dead, maybe, so now’s your cha.ice to get out of it “That made us just hurry to get the boats out, and away we started, and Just as we were getting under way poor Reagan—him that was Kkilled—says, ‘Boys, there ain’t a Spanish bullet made that can kill me. Poor old boy, they sent one clean through his head from the front. and he dropped dead in the boat. “When we began to go toward shore the Spaniards cut loose, and it seemed as if sixteen thousard guns was pour- \«A’ = “ALL THIS WHILE THE BULLETS AND SHELLS FELL THICK AND OUR BOATS VWERE FULL OF HOLES, BUT WE KEPT SHOOTING AND CUTTING AWAY.” Special War Correspondence of The Call. ing balls from hell all around us. One solid shot as big as your head went “between me and Lieutenaut Anderson and just missed sending us to glory by dropping in the water a few inches away. Then the Marblehead and the N ville bega . to give it to them hot, and the Spaniards kept answering with Mausers and from a battery that we couldn’t make out for a while, vntil we saw that the sneaks had played a mean trick. “You know by international law a lighthouse 1s safe in war. Well, what did those Spaniards do but use the lighthouse to throw us off—that is, they put the battery in front of the light- house. “Well, after a while we got about forty feet from the shore, and while some were firing away with their rifles at the men on shore more of us fished for cables. At last we got one up on the boat and began to saw. It took half an hour to do that, and the bullets were falling worse than a thunder storm of rain drops. “I got hit in the right leg. At first I didn’t feel nothing and then when the bullet d my leg felt bigger than a New York sky scraper. A couple of other fellows got hit, too, but we kept our mouths shut, us that didn’t faint, because we didn’t want to make the fellows that was working scared. But Lord! you couldn’t scare them if you told them a ton of dynamite was under them. “And it's a fact, sir, we was over a lot of mines. We found it out after- wards. We saw a fellow—or it was poor Ernest Suntzenich of Brooklyn, that died here after his leg was cut off, that spotted him. I'm getting ahead T of the story, but here goes. ““There was a little house where the cable landed. Suddenly Sunteznich hol- lers, ‘There’'s a Spaniard with whis- kers!" and sure enough, we saw a fel- low running toward the little house. ‘Watch me hit him,’ and he did hit him, too. It was his last shot. A bul- let struck him a minute later and wounded him so that when his leg was cut off he died. Well, the fellow with the whiskers, we found out afterward, was running to that little house to touch off the mines there and blow us up. “‘All this, while the bullets and shells was thick and our boats got almost full of holes, but only five of us and one from the Nashville got hurt. By and by the Spaniards began to feel the heat and ran away to cool off. There was about fifteen hundred of them. The lighthouse battery kept on pumping, but our boys stuck to their work and sawed another cable. “Then we picked up the third cable, but we were about ready to sink and it only went to Santiago anyway, so we went back to the ship.” “What did the captain say to you when you returned?” I asked. “Oh, I don’'t know about that,” was the reply. “When I got back to the Marblehead my leg began to hurt. But, say, here's a fellow that ought to be dead by what the doctors said. Come on, Hendrichsen, and tell how you fooled them.” A young man with timid down on lip and cheek stepped up to me, drew back his blouse and showed me a patch of plaster low down on his rig!’fl ssdo. “I wish you'd tell my friends in New York that the Spaniards couldn’t kill Sl i %o, 7 ATLIANTIC 2, UNTA RAS! KEY WEST) / Y NE ZUELA 'WEST INDIA CABLE. CO. P BERMUDA) OCFAN ", DOMINICA “p MARTINIQUE B\ 5T LUGIA b=\o BARBADOES q GREMDA “BRITISN. CABLECO. AM. S8 g ¥R[N(rl:‘m CAB LECO. FR. . ABLE CO. 8 CANADIAN PACIFIC TEL €O, CANAD SUBMARINE CABLES ACROSS THE SEAT OF WAR. = | CABLES OF THE WORLD ARE "MESSENGER CALLS" IN WAR TIME They are a tremendous advantage over old time methods, and now a naval surprise is almost an impossibility. The recent maneuvers of the American and Spanish fleets in Cuban waters is a fair sample of the game which the cable makes it possible to play in naval operations. Below will t}e found a comprehensive article on how the big powers use this “world-wide messenger service” in war time. ORMERLY when two nations engaged in a naval war it was possible for either to so direct the movements of its fleets as to keep the enemy constantly guess- ing, uncertain where to expect an at- tack. The cable has changed all this. he can direct his own game, whether it be to checkmate his rival or to sweep him from the board. The experience of the past few weeks has proved that a surprise is practical- ly impossible in a naval attack at the present day. Even in the broad At- lantic a fleet is hardly able to shake off the newspaper correspondents who can always reach some cable office in time to inform the world of its move- ments. On its first approach to land, whether that land be hostile or neutral, there are more correspondents and agents of the enemy’s government to herald its approach. The cablegram can travel a million times as fast as the swiftest cruiser and with the pres- ent network of cable lines it can ‘ travel to almost any corner of the globe. It was the cable that made it possi- ble in the present war for the Ameri- cans to win theit first victory on the opposite side of the world within ten days of the declaration of hostilities. It is the cable that has permitted the officials in Washington to follow and direct the movements of the fleets under Sampson and Schiey and Howell, and to keep tabs on the Oregon during her long journey around tne Horn. As soon as Spain’s flotilla left the Cape Verde Islands the cable made it known in Washington. In all the isl- ands of the Caribbean men waited to announce the fleet’s appearance. It ar- rived at Martinique. The news was flashed to Washington. ‘Washington flashed its orders back to Sampson. Sampson moved east. The Spanish squadron disappeared. In a day a cable- gram from the Dutch island of Cur- acao announced its arrival there. Again the news was flashed to Sampson and again Sampson changed his course in accordance with its import. This is a fair sample of the game which the cable will make it possible to play in any naval operations. Of course it is a two-bladed weapon. Spain has been as well informed of the move- ments of the American ships as we have of the performances of the Don’s sailors, in some cases perhaps better. Spain controls more ends of the many stranded line than does the United States, at least more of the ends that are of importance in the present con- test. This may lessen the advantage of the new war factor from our point of view; it does not lessen its import- ance. A perusal of the war news of the past few weeks may have given the reader & better idea of the cable system of the world than he had before, but at best 4t is likely that his conception of its magnitude is hazy and incorrect. For his instruction it may be mentioned thut there are in rough numbers 209,000 miles of cable under the rivers, bays* and oceans of our little round earth, and that these are under the control of some thirty different goveraments and 2s many private companies. This great stretch of wire weighs probably 8000,- 000 tons and is enough to ‘encircle the globe eight times. As a matter of fact, it:does not really encircle the globe, The Pacific has never been spanned by the cable, but the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and nearly all the smaller seas have been crossed by it. The furthest stretch at present traversed by the line of elec- tric communication is from the West- ern coast of America across the Atlan- tic, Europe, Asia and Australasia, to the French penal settlement at New Caledonia, in the Pacific, which is be- tween 4000 and 5000 miles from San Francisco. This side of the world is well sup- plied with cable lines. There are ALASKA CANADA PACIFIC OCEAN THE SUBMARINE k CABLES OF THE WORLD MAP OF THE SUBMARINE CABLES OF THE WORLD. T Amtaica me,” he said. “I was slated to die, but here I am and I'll be fighting again if they don’t hurry up and finish this war. You see this plaster in front of me cov- ers an end of a hole that goes right through me. The other end is in my back. See—" and he showed me a sim- ilar plaster, but larger, that covered the place where the Mauser made its exit. ‘While Hendrichsen was showing his wonderful wound to me a man in a neighboring bed sat up. His head was swathed in bandages and he could not tal but at a sign from him ‘‘Jack” Davis briefly told me his story. His name is Robert Volz, his home San Francisco and his ship the Nashville, “He was hit six times,” said Davi “and two bullets made wicked tracks in his head. Others grazed his body, a couple of them just being far enough out to miss his heart, but they made their marks just above it. He'll be all right in a few weel J. J. Doran of Fall River, Mass., a boatswain’s mate on the Marblehead, was also in the hospital. He was sleep- ing while I was a visitor there. His in- Juries are not serious. From the barracks hospital I went to the convent, which has been turned over to the Government, and there I found battered heroes of the Iowa at San Juan. First was George Merkle of New York, a private of marines, who was so badly wounded in the right arm that the doctors cut it off last Sunday. Only two of the men there were able to tell their story. They were John Engle of Baltimore and John Mitchell of New York, both able seamen. Mitchell was wounded by a fragment of shell that tore to his ribs on the right side and Engle carried crutches because of a damaged right foot. “The bombardment of San Juan,” said Engle, ‘“was mostly amusement for the men on the Iowa. We didn't lose a shell we sent toward the bat- teries, because, you see, ever since the Maine was blown up we have had tar- get practice nearly every day and we had no excuse for wasting ammuni- tion. “I remember that I heard one man who was at a gun with me say every time she was fired, ‘T wonder how many Spaniards that hit?" “How did we feel under fire? Why, Just full of fun. The boys were sing< ing, and down on the berth deck, ‘where the batteries were being held in reserve, they had a series of waltzes while we were at work in the turrets and on the spar deck. There was singing and cheering and some of us enjoyed good smokes while the firing was going on. ‘“Suddenly a shell burst over our heads and there came a rain of metal. The doctor rushed up from the sick bay and asked the chaplain if anybody had been hurt. “The chaplain said ‘Yes,’ and they took three of us below. That stopped the gayety for a while, and some of the boys crowded down to see how bad- ly we were hurt. They went back to work in a minute, though, and as soon as they saw the damage done by the next gun they cheered harder than ever. “We didn’t fire so many shots at the forts. The Spaniards wasted an aw- ful lot on us. We just fooled them. The ships on which pieces of shells fell were not the ones they almed at. We were sailing in column in a circle and firing when we got in line with our ob- Ject. At first we went by at twenty- one hundred vards. The Spaniards tried to get that range, and I suppose they got it, but our next move was to go in at eighteen hundred yards, and the shells from the forts went over us. Of course, some of the ships going around the circle were at the twenty- one hundred yard distance while we were farther in. That was how the New York and Jowa happened to be hit by bursting shells. The Spaniards aimed at the inside ships, they thought, and went away over them “How did you feel when you wera hit and what did you do?” I asked Mitchell. “I didn’t feel at all,” he said, “but something made me whirl around. I didn’t know what it was and went back to my gun. I worked there for a while and enjoyed a quiet smoke, and then somebody called my attention to my coat and the red on it. T felt sore then, and knew I had been hit. The shot was a mistake, though, because the gunners never hit what twelve of them crossing the Atlantic. Of these five belong to the Anglo- American Company, three to the Com- mercial Cable, one to the Direct United States, one to the French Atlantic, and two to the American Telegraph and Cable Company, which is operated in connection with the Western Union. The many lines and the resultant competition have brought the cost of communication between New York and London down to a fairly low figure, 25 cents per.word, but when one tries to reach more remote parts of the k] sovr 7 world, where the line is controlled by a single government or company, oOr where there is little business to sup- port it, the cost of sending messages mounts up to alarming figures. To send ten words from New York to Manila, for instance, costs the mod- est amount of $24 50, or $2 20 per word beyond London. This is the commercial rate; newspaper dispatches go for about half this sum, but even so the cost of bringing a column of news from the Philippines mounts up to nearly four figures. v