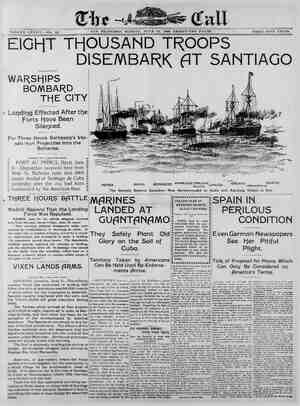

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 12, 1898, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

“STOOD SIX FEET FOUR OR I'M NO JUDGE OF INCHES.” N the morning of the twenty-third of May four men went out from the regular Army to serve their time in Alcatraz Prison. They were placed under guard in an open express wagon and driven from the Presidio guard house to the Clay-street wharf. As the wagon passed through the Reservation gates on- of them flung himself into the bottom of it and covered his head in his arms. I think no one noticed these men or noticing took much account of them in the hurry and bustle of that day. It was the day on which the First and Second Battalions of California Volun- teers broke camp at the Presidio, marched across the city and took ship for hostile ports. In the chill, still dawn which crept into the field Z.om the sea the reveille woke eighteen hundred men to the ac- tive service of their country. They rose to it eagerly and stirred the Post with the business of their going. Who, seeing it, will forget while the heart beats in the breast, that first call to the young West and how her sons went out to answer it? There have been wars of ours In which men fought and bled and died for the cause and the flag floating over us, and left their legacy of national courage to its his- tory. We read of them, thrilling to their memory, and honor such as live to tell the tale. But th.t was the courage of long ago touching the heart across the years of peace. This is the courage of the vivid now, going from our arms in answer to the trump of war. Those were our heroes of yes- terday. These are our soldiers of to- day. Those were the wars of our fathers. This is the war of our sons. In the little hours of the dawn the crowd gathered: at the Presidio to look on the orderly confusion of breaking camp, the figures of men and horses coming out against the lightening sky, orders: sharply given, quickly taken, the eager stumb- ling of the raw recruit, the excited cool- ness of drilled militiamen, the frenzied zeal of company to surpass company in the speed of packing tents, the magnifi- cent triumph of the victorious first, the splendid disappointment of the defeated rest, the traps loitering on the drive, the equipment wagons lumbering on the field, the close embrace, the sound of laughter and of sobs, the words that courage speaks and pain, the assem- bly, the start, the march, the band, the flag, the boys! ‘Who, I say, will ever forget it? Who vants ever to forget it? Cheers, tears, good-bys, godspeeds all along the line of march! All the early wakened world gay and sad at the sight of so much young courage and tender patriotism and innocent hope going to the war! The city with her natifonal colors at her breast, pulsing and throbbing with the spirit of war after a thirty years' sleep of peace! California wreathing her roses and lilies into crowns for untried heroes, sending them forth to win her laure Young boys chafing, old men mourning the glory that passed them by! Moth fathers, sisters, sweethearts, wi giving bravely their dearest and besi! The music of fife and drum getting into men’s legs and making them march! The sight of the old flag getting into men’s brains and making them mad to go out under it, to fight for it, to die for it! Scarce one among them, good or evil, but would sell his rights of birth. his hopes of heaven for the chance. And away from the line of march, away from the flowers and the flags, the cheering and the glory, away from the transport ships, away from the wars, away from the Army, going to the Clay-street wharf, going to the Government tug, going to Alcatraz Island, going to the military prison, men who had this chance and put it behind them. And one, face downward, in the bottom of the wagon. R S R . . e I went to Alcatraz Island on ‘Wednesday. Captain Hobbs, commandant of the post, stood on the wharf. Lieutenant England, officer in charge of the pris- on, stood beside him. It was a rough day by land or sea, with a spit- ting fog abroad. The sea- girt short of the grim- mest of our posts was washed with soapy water, its rocky steeps were swept by a bold, brisk gale. Men held to their hats and women to their draperies. The closed sides of the little omnibus that crawls like a beetle up and down to the top of Alcatraz and to the bottom shivered in the draught. The commandant shouted to me down the wind: “Ride up. I will join you at the of- fice.” And the beetle crawled where man, cleverly disposing of what God pro- posed, has hewed and hacked himself a road from out the nearly solid rock. Nasturtiums, sea pinks, wandering ivy, all brave things that root in rock and bring color to the face of it, are planted here to cheer the eye, good soil is boxed and ledged from sliding to the sea, and garden things set out to grow in ft, the sturdy marshmallow flings its supple branches out and swings and nods as pinkly, greenly gay on Alcatraz as any- where; but the beaten roses droop and scatter in the deathless wind, tender clinging vines are swept from the walls, flowers bloom palely, grass grows sparsely, trees grow mnot at all; Alcatraz, fog-swept, wind-blown, rock- built fortress of the sea, looks what it is to saint and sinner in the service, the prison post of the Western Division of the Army. In the little office which looks,.like a lighthouse, on all sides to the sea, I make my wishes known and hav: them granted. They are, tout simple, to go into the prison, to talk to military conviets, to know from the eyes, the lips, the voices, the manners of these men once enlisted, and now debarred from the service of their country, how this fact feels to them in time of war. It is against military rule for the civilian, even in petticoats, to hold com- munication with military convicts ex- cept in the presence of an officer. Cap- tain Hobbs and Lieutenant England go with me to the prison. It i{s that long, brown, melancholy building lying to the water and seen of every passing craft, with its port- holes, lighting cells, looking to the sea, the windows and the doors of its free passages giving inward to the road up- on the hill. The men were at mess. In a long, low room, whitewashed, sanded and scrupuiously clean, twenty- four prisoners were gathered to the midday meal. They sat on benches at either side the single table running down the middle and nearly the length of the room. They were all young men. They were nearly all good-looking men. That is to say, they looked out from their eyes frankly, held up their heads bravely, had an average of good feat- ures among them and none of the hang-dog look the civil convict wears like a brand upon his brow, like the stripes upon his back. It occurred to me then in the face of the contrast as it has occurred to me many times before in the lack of it, that the stripes have much to do with this. The military prisoner wears his old uniform, or the old uniform of somebody else, stripped of its honorable buttons and dyed from its martial blue to any dark and serviceable shade the cloth will take. He wears a soft black hat with a red band about the crown when he is entered in the second class of prisoners—as all prisoners are en- tered at the military prison—and he may earn the w’ite band of the first class by good behavior, or fall to the yellow of the third class by evil ways, and in any case his standing is shown in contrast to that of his fellow prison- ers and he may not be confused with something better or worse than he is. He walks np lock-step; he knows no chain gang; he -is given a certain liberty of action under surveillance; he is treated like a man in disgrace, but like a man for all that; he is suffered to take away from prison as much self- respect as he brings into it. And this is a lesson the law might learn from the army! It is the principle of civil prisons to break down what honest pride may sur- vive the sinning of a deadly sin‘and the loss of personal liberty. It is a part of the punishment which is supposed to fit every crime. For this the lock-step, the chain gang, the ball and chain, the convict stripes survive thelr usefulness, live on in the face of surer, more scien- tific methods of defense against escape and means of recapture. For this the man who steals for galn and the man who steals for bread, the man who kills in hot blood and the man who kills in cold, wear the same uniform of shame and no man, seeing, knows them apart. And yet it would seem to me that pride is as good a thing to cherish in the hearts of bad men as in the hearts of good, as necessary to men in prisons as to men out of them. For it is not until pride is gone that the candle is out and darkness eternal set- tles on the soul. B0 e Gk MR T LR SRS “Attention!” The men at the table dropped their knives and forks. Their eyes looked straight away over their noses, their hands fell to thelr sides, their meat apd cabbage cooled on their plates. They were tense, motionless as stone men, every nerve under the discipline which makes the strength of ,the army. Through the open panels of a sort of screen wall at the end of the mess room I could see the kitchen. The cook had come to halt before his range. The helper at the sink, the steward half- way from the table to the door. Their perfect obedience to discipline lent them dignity, as obedience to discipline, in form or effect, dignifies all men, even soldiers disgraced, stripped of their buttons,” dressed in dyed uniforms, do- ing time in a military prison while their country is at war. The Captain stepped across the sanded floor. “Let the men go on with mess,” said he. ‘At ease!”™ The men at the tables picked up their knives and forks, the cook in the kitchen fell to his pots and pans, the scullion stirred his dishes, the steward moved across the floor. The table was trimly spread, the fare was plentiful and inviting of its kind, the men ate with relish, pushed away their plates as they finished, rose and left the room when they liked. Their hats hung on a row of sen near the door. I noticed the bands of red and white. #‘Artillery and Infantry?” I asked. “No,” said Lieutenant Fngland, “sec< ond class and first.”” And he explained the distinctions, including the yellow, and mentioned that yellow was an in- frequent color in Alcatraz Prison. &0 T S e ke e e “This man has jua} come over,” sai@ the Sergeant. This man was the steward, six feet four or I am no judge of inches, and never saw twenty-five or I am no judge of years. He looked a handsome soldier and, by my faith! a brave one, standing there in his six feet of disgraced strength with a napkin on his arm. He stood well, with his chin up, hig chest out, his shoulders squared, hig heels together and his hands clapped to his sides. The officers regarded him thoughtfully. Such men are needed to- day in the field. His eyes met mine steadily, but his face flushed. It was a good face, well and squarely boned, the brow and nose strong and straight and Greek, the lips firm, the jaw set in the outward curve with which Greece corrects the exaggerated beauty of such brows and noses. He waited like a man walting for execution—brave to meethis fate, but by no means cheerful about it. And it is not so easy to talk to men in trouble. T mouthed the Sergeant for a moment’s grace. “So you have just come over?” “Yes, madam.” “What—" I began and hesitated as to the putting of it and began again. ‘“What was {t?"” “Fraudulent enlistment, madam.” 'What was there against your enlist« ment In the regular way?” His eyes flickered and his color rose, He hesitated a moment. Then he said steadily enqugh, “T'd deserted.” The answer surprised me. This man d no look of running away about him. Vhat for?” I asked abruptly. d rather not say,” he replied quietly. i “I beg your pardon.” “No!" he said, looking distressed. “T didn’t know there was going to be war,” he added. “It was from the Fourth— the Fourth Cavairy—and when I heard about the fighting, I enlisted again, right away, in the Fourteenth Infantry, That was in Oregon.” “You came down with the Oregon troops?” “Yes, madam.” “And they took you at the Presidio?™ “Yes, madam.” ‘““How did they find you out?” “By the description card, I suppose. It was quite awhile that they didn't and I hoped that I might get to the front—"" he looked dejectedly away. “You wanted to fight?” “Yes, madam.” “I think you ought to let him,” I said to Captain Hobbs, as the man went back to his table. “Don’t you think he’s a brave man?” “I dare say.” The Captain shrugged his shoulders. “And there isn't the slightest chance for him now?” “Not with us.” “I hope you don’t mean with Spain?" “No,” said Captain Hobbs. “But there is no regulation to prevent the en- listment of a man from here with the Volunteers. If they knew him for a military convict very probably they wouldn’t have him. but it he could get somebody to give him a certificate of character that would pass muster at the recruiting office there is no military law against his using it. I understand several non - comm oned officers among’ the Volunteers are discharged military convicts.” “And then,” said I, faithful to my brave, “if he distinguished himself in the field and did something particularly heroic, you'd forgive him, wouldn’t you, and take him back into the army Wouldn’t you?” “I?" said Captain Hobbs. “I couldn’t. The President might.” o S AR S e e I saw the others in the gallery leading to the cells. Its bricks are painted white, its roof is glass. The sun shines here when it shines at all. The salt breeze from the sea hurries in and out at the open portholes past the grated doors and sweeps the gallery clear. Here is no foul prison smell, no dank prison slime. The cells are clean as that wam which _has become a housewife’s prov- erb. Bach is furnished with an army cot, painted white, a dresser and a chair. All are decorated, by their in- mates, in that spirit of home adorn~ ment so touching in captivity. The men came singly and stood against the whitewashed wall and ans- wered questions. Their military man- ners served them well. Some were shy and some were shamed, but they all stood rigidly erect and gave their ans« wers promptly. They all wanted to fight. One man was there for insubordina- tion; he had struck an officer and he did not care to talk about it. The rest were deserters. “Where were you taken?” I asked an Irish eve which twinkled even under conditions such as these. “Shure, Oi nivver was taken at all. Oi came av me own accourd.” “That's not quite usual, is {t?” I in- quired politely. “‘Faith, thin, it is. There’s lots av poor divvils come and give themselves up and that's all the good it s to them. Ol deserted wanst, but whin Of hearrud the war news Oi wint shtraight away and gave meself up and said O1'd loike to foight.” “And—?" The Irish eve winked takingly. “They thought me country wouldn’t need me for about two year-r-s.” But it is not every man can take a light Irish heart to prison with him. The next had given himself up because he could not believe the Government would refuse a man who wanted to fight. “Didn’t they want me for deser- tion?” he said bitterly, ignoring the presence of the official braid. *“Wouldn't they have held me for that if they’d taken me? And I went and gave my- self up. I was sick of being what I was. I wanted to serve again. And I'm here serving—serving time.” Oh, wise government of the people, for the people, by the people, and which Continued on Page Twenty-Sim -