The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 3, 1898, Page 25

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

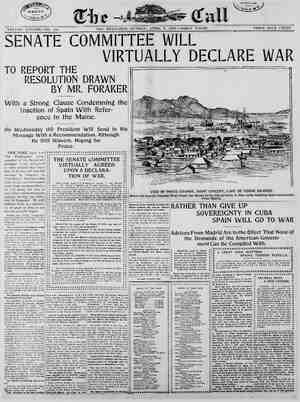

THE SAN FRANCISCO TALL, SUNDAY, APRIL 3, 1898. BAN FRAMCISCO R et =B romize is that e to: -~ around And not only is th.. promised, but it is almost an assu a concession for tance-seer” apparatus anted for the Paris Exposi- nd there are millions of has bee tion i 1900 nd the promoters. The in- 1m 1ave been tested and there is no doubt that everything will work g exposition opens this of the century will be so that all may see at 1. That it will draw ving. of the promoters to s scenes from other Wherever wires can s can be taken and ated comfortably 7 look upon the Mount Etna and a ng an 1 snow of Mount 1l the big duced, and atc be on the pa le name of Herr Galician by lana- ¥ nta- ng particu- as to the and ed , which can be At the re- trans- y of at the receiving end transmitting end. e coated with >, Across this traight-lined or knife, v linear strip of The pur- a single line of observation may be lective influence of mirror (the first one In ct is reflected) xed on ans of which (with the ectro-magnet) it is con- at the lines of rvation are con- up into points by means of the llating mirror, which is at right to the first, so . 1s at right angles of the first. As each other in a t only a single point > of the first mir- the second mirror, ror will app: and therefore only the reflected ray which corresponds to this point will be reflected in the The two TOY! illate This ray of light, which corresponds - LASHING __- .3 I 5130 Shal> By il ‘;—-1 o ) ddeddr Y LouiS to a certain point in the picture, is con- verted into an electric current by the employment of an electric battery with a selenium cell. The property of a selenium cell is that its electrical re- tance varies with the color of the light to which it is exposed; it is ener- gized in different degrees by different T A blue ray, say, will have a y powerful effect upon it, while a red ray will set up a very weak cur- rent. This electric battery is connected by wires with an electro-magnet at the re- ceiving end, swhere the electric currents are to be reconverted into rays of light. The electr agnet will accomvlish this by moving in sympathy with the elec- tric current sent out from the transmit- ting apparatus, and its movements will arily correspond to the nature of reflected. A blue ray, for in- stance, would move it a considerable distance, while a red ray would only ghtly deflect it. Now this magnet is made to move a prism, which is placed in front of a B white light—either the light of the sun or an electric light. The action of the prism will break the white light are spread out in a spectrum. sm being moved by the electro- mag it will necessarily revolve just so far as to bring the required color color will now be reflected in one of the two oscillating mirrors at the receiving end. And just as the action of the other two mirrors was analytic so the action of these two is. Each point of the picture is reflected on a screen, and as the points follow one another in very rapid succession in- deed, the eye of the observer will take in tr impression of the entire plcture its points were all presented to it simultaneously. The picture can be made to last as long as may be desired by constantly reproducing the effect, and at such a speed that the observer is unconscious of any break in the process. It Is no more difficult to reproduce a moving picture than a still one, for the inven- tor explains that “it is the actual pic- ture which is reproduced, and not a mere record as in the case of the kine- matograph.” Another point claimed is that there is practically no limit of the distance within which the apparatus can be used. With the possibility of a tele- phone wire 1000 miles long, such as that between Chicago and New York, the tor thinks that the telectroscope might be of any length. Such an instrument, of course, opens up a wide field of possibilities. Scenes of foreign travel, battle fields during action, and the eclipse of the sun are only a few of the things we might have seen recently, while sitting comfortably at home, had Herr Szczepanik had his machine well established a little earlier. As it is, the question arises, has not this Galician genius done away with the necessity of visitors actually going to Paris in 19002 Like most other inventions that are for the reproduction of any kind of vi bration the telelectroscopeseems to have one or two weaknesses. A number of sclentific men who were given a private view of Its workings, whilesurprised and pleased even beyond their wildest ex- pectations, stated to the editorof a Lon- don paper that “the invention seems to have been inspired by the kinemato- graph, and it is said that the images resemble to the kinematographic im- ages, and are shivering like these.” Again, “Thence follows that the image does not appear in the natural colors, but in the corresponding spectral col- ors, and the colors in which the image appears are not quite clear.” But such a slight objection at such an early hour after the inventfon can surely be overcome in a short time, possibly before the opening of the Paris exhibition. After the Paris exhibition it is the in- tention of the promoters of the telelc- troscope to exploit it in all the big cities of the world. Of course San Francisco will be in- cluded, and when that time comes you can step into the place when the ap- paratus is on exhibition and see what your friends are doing in some of the <Jle o) ) ) big citles over a thousand miles east- ward of us. The most remarkable feature of the inventionof the telelectroscope is the in- ventor himself, because he proves in his person that inventors are like artists— born, not made. Jan Szczepanik is an Austrian Pole, and only 24 years of age. He was so poor that he was forced to quit the university and become a gchoolmaster in his native village. Three years :~0 he apolied, in a crudely written letter, to the Austrian Ministry of War for assistance in pat- enting his “Fernseher.” But Austria is a country where in- ventors proverbially go a-begging, and nothing might have come of the young man'’s discovery had he not been taken in hand by a Vienna banker, Herr Lud- wig Kleinberg, who may virtually be said to have discovered the Edison of Europe. Indeed, it is confideatly pre- dicted of this stripling that he will leave Edison far behind. He is said to possess very little tech- nical knowledge; but in spite of this fact he was able, the moment he set eyes on a silk-weaving loom, to hit upon an idea revolutionizing tl.e manu- facture of Gobelius, which, b means of an electric. ] process, can now be produced at one-twentieth of the for- mer cost. The p.tent ha: just been sold to a ring in England for $250,000. Pictures of any dimensions can be pro- ducel in silk within a quarter of an hour, and thes have the truth of pho- tographs as well as the artistic value of a steel engraving. DREARY WORK OF A LAUNDRY GIRL One Week’s Experience of a Woman Among the San Francisco Laun- dries to Ascertain How the Girls Work, How They Are Treated, How They Are Paid and How They Live. ONDAY morning I applied for work at the San Francisco Laundry and got “on,” as they say. Nine others had applied, two quite young girls in short dresses. I was to receive $10 a month, board and room. I was taken to the mangle room. I hung up my hat and coat and began to earn a living at laundry work. My first task was to fold towels, piles and piles and endless piles, hot fromthe mangle. As I made the acquaintance of the San Francisco hotels by the qual- ity and color of the towels, I wished to look about, but with the eye of the “forelady” on me I attended strictly to business and folded “two times twice” and “three times over.” After countless hours I was told to ‘“come along,” and I went. At another table I shook out wet pillow-slips and piled them up, hems all one way, and tried to keep out of the way of an old man, who trotted about with piles of wet linen. He whistled at me and told me to “get along there,” and when I did not get along sufficlently quick he threw my pile of pillow-slips in a heap and swore. and defiantly said, “What are you go- ing to do about it?” Perhaps 100 men and girls were crowded into the room. The steam from the wet clothes in the hot mangles went to meet the steam from the washers and rolled about in clouds. The machines slopped suds on to the floor, where the water stood in puddles. ‘With my feet wet and the hot mangle at my head, in the awful atmosphere where an occasional kindly breeze, strong with ammonia, cloaked the con- tinuous odors of soiled linen, I only wondered what girl could stand it for five years. The overseer came through occasionally and looked sharply about, and the forewoman was ubiquitous. With a tongue in place of a lash she told this one to hurry up and that one to “be lively there.” Woe to the girl caught talking! She was reminded in no mincing words that “it was not to talk she was hired.” A shrieking noise, the dinner whistle, made me drop a pillowslip on the dirty floor. This did not escape the eves of the “forelady,” as she checked the girls till their work was left in order. The backless wooden bench, where I found a place to sit at the long dinner table, seemed a God-given luxury after Zytia;lndl{xg for five hours. A pretty little rl who sat n ot ext to me, just 14, helped It was “Nick, give me so 7 and “Nick, hurry up with tr}:‘ftbxrfeaalz"’ shile o handsome young man in his irt sleeves flew vai lfll%ihungry L about and waited on alf an hour for dinner w Finutgs off in the beg!nnln"nihs ‘;Amrle‘; honilriy?“ue’ and every one was in a For supper only twenty m %l]o\\'ed, and then it s a zush”;;léeeseda{: bfo\:?;Ck to work when the whistle We waded through the ater wrfs}_]room floor to get ol?l- to <?1’r‘m‘eh: Every one worked steadily, scarcely s i A ! k j iooking up, as if each were engaged in a neck and neck race. I saw no one loitering. As the hours went by and the shadows cr-pt farther out into the washroom the faces became more and more tired and drawn. The whole room was alive with machinery, and the whirling wheels and belts and the deafening noise made me dizzy as I walked between the machines to where I was to help shake out bedspreads, pile after pile, as fast as I could. Wet bedspread® are heavy. My head ached. It was as if time had forgotten to go on and I was a machine. An old man came in, walked about and looked sharply at everything. As he stood rubbing his hands, gloating over the piles of linen and noisy machines, and men and women, counting his profits, a feeling of rage came over me that he could hold us there in slavery—that weak, old man. To him went the profits, to us the deadening toil. I wondered that no one hurt him, but none seemed even to notice him as he stood there. The white, unhealthy faces of the girls told their own tale of working from 7 a. m. to 9 or 9:30 at night, as they were doing until some weeks ago. Then the girls sent word to the Com- missioner of Labor. The hours have been shortened since, but it has been a duller season. Soon the summer will increase the amount to be got out and then? Only in the mangle-room, how- ever, have tLe hours been Iimproved. There unremitting vigilance keeps the girls at the highest tension for sixiy- two hours a week at the rate of about 4 cents an hour, and at work which makes them wern-out, old women at 20 years. In other departments we found rirls working seventy-one hours'a week. Ev- erythingis arrangedwitha view of profit to the corporation from the artesian wells to the regulation whereby one who earns 35 cents per day receives 15 cents if she work half a day and loses 20 cents irrespective of which half she may work or lose. The sick list is an eloquent commentary on the system. Girls are always absent for sickness, losing their pav Those who work after hours receive no extra pay. The room allotted to me as my sleep- ing room recejved its entire supply of air for three through a transom over the door into the hall. Two beds nearly filled the room. No springs under the filthy mattresses, no pillowcase on the dirty straw pillow, and the bedding in a condition indescribable, made me de- cide that I would go home to sleep, as very many of the employes do. There are not rooms enough for all, although the room and board are in- cluded in the wages. The room was furnished with two chairs, no tables, no bureau, no closet. An old man has charge of the oil with which to fill the lamps, but his fre- quent absences are so many cents on the right side for the company. So. nothing is sald, and the employes either buy their own ofl or sit in the dark. Men and women take care of their own rooms and even make their own bed linen when they can get it, which is not always. I asked Mr. Blggy of the United States Laundry what they counted as the cost per capita to board the em- ployes. He told me $ a month, and at the United States it is optional whether the employe has or has not board. If he boards himself a difference of $5 is made in his wages. Not so at the San Francisco. Nearly all of the girls have homes which they help support out of their slender wages, and this $5 or a third of their entire wages, would be a great help’ at home. The quarters of the men are adja- cent to those for the girls. There is no discipline, no restriction put upon either; and such an atmosphere can- not but be deteriorating to a young girl whose sole home is an airless room during the Sunday hours when she is not at work. In not one instance did I see any pro- vision whatever for the comfort or con- venience of the employes. In the en- tire laundry there is not a chalr, though in other .laundries we found girls sit- ting at their work and doing it quite TELECTROSCOPE RECEIVER IN NEW YORK. By This Wonderful Instrument the Scene in Paris Can Be Reproduced in. the Most Minute Detail.. as quickly and as well. If the girls are ill they are in their rooms, and if friends will carry them food, all right. Everywhere the smaller mangles are heated by gas, and being exactly in front of the operator’s mouth she must breathe this hot air all day. In one laundry only we found protectors; they can be put on at a very small cost. One man I found, who was a pathetic example of the system. His voice was quite gone, and to any observer it is but too evident how nearly his days are done. It was all right; he had nothing to say against the laundries. People were willing to work twelve or sixteen hours a day and glad to get the chance. When folks are compelled to work, they expect to work. In one breath he told me it was a frequent thing for a man to lose his hand or - part of it, and he was lucky if he could get back to work when the injury had healed. Scarcely had he finished the sentence when he took it back and said the laundries were all right. When he got stronger he expected to go back and would not hazard his chance of em- ployment—not to save the lives of all the rest of the world. It seems very unfair that laun- dries like the Ta Grande, White Star and United States should have to compete with the sweat shops, and yet none of these seem to be in danger of immediate bankruptcy. Their employes have reasonable hours, get good pay and are healthy-looking, in great con- trast to the white, drawn faces and bloodless lips at some of the other laun- dries. Mr. Biggy is the vice-president at the United States and the superintendent. The girls there are healthy, not worn out and can get their work finished and be home at a good hour, for there are no girls in the boarding-house at- tached to this laundry._ We found Mr. Biggy bandagin~ the hand of a girl who had been injured. Her expenses and salary were pald during her absence and Mr. Biggy hopes to be able to have the hand as good as ever. The girl works a few hours a day, receiving full pay, al- though the accident was her fault and caused by wearing a ring, contrary to rules. The Electric should come under no- tice of the Board of Health. The St. Nicholas was quite as bad. It was a peculiar place, tumble down and {lly ventilated, with a toilet room without water, off tl.e room where the girls work. The manageress tried to impress us with the fact that it was a small paradise, and that her dear girls scarcely worked at all, and were well paid for overtime. The girls told me the same and her pay roll was a thing to admire. Later I went upstairs, and Mrc Green of the Labor Commission talked to the girls without her, and they de- clared it was a common thing for them to be working at 11 o'clock at night. Never did they receive any extra pay when they signed the pay roll. I have visited many of the homes of the girls, and have seen how indispen- sable is the pittance earned, where small girls are supporting sick mothers or fathers and small children. It is pit- iful that these young heroines are not protected by the same law which would be quick to find them if they trans- gressed. I went home with a woman whose face had attracted me in one of the places where I worked. It was only a short distance from the laundry and was much cleaner than the appearance of the girl had led me to expect. As we went along, looking into the uncur- tained windows at the family groups, Nora’'s steps quickened. In one a man was rocking a baby to sleep and smok- ing a pilpe, while a woman sat near mending, her feet on the hearth of the cook stove. Nora sald it always made her feel wicked when she went home at night, empty handed, to her babfes, who were alone all day, for she must eat at the laundry, and what she earned only bought enough to keep them all aliva and clothed. The children sat quietly on the floor, waliting for her to come and give them supper. The room was dark, except for @ street lamp. They were very glad to see thelr mother. The small boy had his share of the caressing, too, but he remembered something, and was in a great excitement. “My Miana can go, my Minna can go,” and he pulled the tiny girl to her feet, where she bal- anced alone. Then he ran to the other side of the room and held out his hands to his sister, and sure enough she walk- ed straight off to him, but her pride and excitement were too much to be carried by the little legs and down she went. Then such a praising and petting and hugging as the girlie had! On the floor were scattered a few toys end in the corner & box sand ADS A AL TELECTROSCOPE TRANSMITTER AT WORK IN PARIS. The instrument can be placed in any position where the desired view can be obtained. mechanism the entire scene is received on selenium plates and sent to the receiver hundreds of miles away. By starting a clockwork was the little one's playground and the only ground they ever saw except on Sunday. Three chairs, a table, a bed, a cradle and a cooking stove made all the furniture. On the floor, a pil- low, dented and soiled, with a nurs- ing bottle beside it, told how the little ones rested in the long hours they were alone, for Nora could only run home a mo- > ment at noon. In a few minutes she had their supper ready. “Corn mush seems more satis- fying than -any- thing else I can get,” and with a little milk and su- gar the children seemed to think so, too. After the little ones were in bed Nora got out some sewing and worked bv the light of a candle. I was tired to death and went to bed and it seem- ed only a few min- utes when Tommy climbed {nto bed and woke us up and Nora said we had overslept and must hurry to be at the laundry in time for work. Breakfast was the same as supper. Nora had taken out a small quantity of the yellow mush, and, to my inquir~ ing look as she placed it back on the table well ous of the children’s reach, she said: “Tim might come, and he'd like a bite to eat, for he’d be down in the mouth and ashamed, and me away. Oh, I known I'm a fool, but you see—well, Tim's Tim. Maybe you’'ll have a man of your own some day and you'll know how it {s.” St. Joseph, to ‘whom . she prays, must be _iIndeed deaf and dead if he does not hear this poor ‘washer lady” and take care q of Tim and send him back to the overburdened mo- ther. This woman works eleven to eighteen hours a day and receives $13 a month. As. we walked along Nora told me of a girl who had worked with her. 1t troubled her much thinking of her own lassie at home, but she could see no way out of it. Lilly'sparents had come from Denmark. Her fa- ther had been able to earn a good many comforts for his family, and at his death his wife owned her home and a little money besides. Lilly had hoped to get a good education, but when her father died she had left school and gone to work at the laundry. Like most children of Euro- pean parents, every cent she earned was carried home, and the mothercould spare little of the scanty $10 a month for the girl herself. Two years past she worked every day from 5:30 till 10 at night, for her duty was to be there to dampen the shirts ready for the ironers at 7. Like all young things, Lilly saw only never-ending grind of her labor; no time ever except on Sun- days, and then her one desire was to lle and sleep. She earned so little she could have nothing herself of the pleas- ures girls live for, and saw no hope but to become worn out at 20, as the other girls were. One morning Lilly did not g0 to work. Nora tried to find her. She knew how the girl would need a friendly word, and to her own family © she was worse than dead. As Nora said: “Well, God, he konws.” At another place I had met the moth- er at the laundry where she had gone to take something to her daughter who worked there. Such a sweet old face. She said she was sorry that she had troubled me. She had cried when I spoke to her and told me that her eld- est daughter was at home very ill and that as at home she never dared cry and relieve her feelings, so she always left the house when she wanted a good cry and couldn’t keep her tears to her- self any longer. She asked me to go home with her and see her daughter. It was a bright room with the air ~¢ home. A few plants, some few prints adorning the walls, some sort of savory mess cooking on the stove in the cor- ner, and the sunshine flooding the room and brightening the girl who lay on the couch with her eyes closed, made it hard to realize what the woman had told me. “She was such a strong gir], but she * began to work before she was 14. You see, my man died and there was six little ones and we had to do the best we could, not what we wanted; and she was the oldest. At the laundry she earned $7 50 a month, and as the girls were old enough they went there too. They have to work and do not know how to do anything else, and the wages are so small they never have anything left, so they just have to take what comes. “One of the girls goes to work at 5:30 and has worked till sometimes 11:30 at night. The others begin at 7 and work till often 8 and 9, and it is just killing them. Mattie will never go back again I know, but it just breaks my heart to see the others going the same way. They will all break down soomer or later, and there seems to be no hope.” HELEN GREY. —_—— ANOTHER BALLOON ASSAULT ON THE NORTH POLE. N expedition directed by M. Va- ricle, a French engineer, who has made a specialty of aerostatics, will soon leave for Juneau, tak- ing along a flotilla of aerostats, of which the Alaska will be the pilot- balloon. The project has been carefully stud- fed by M. Varicle, who has recently made several trial trips in company with M. Terwange, a distinguished traveler, who has received the degree of Doctor of Laws; M. Besac, an engi- neer, and M. Richard, an expert me- chanic. All these trips gave satisfac- tory results except the last, made from the French city of Lille, when, the re- lease being made before the captain gave the order, the balloon, called the “Fram,” falled to clear the houses and was brought back to the starting place too late for the ascent to be made that day. Previous to that M. Varicle had made the journey from Paris to Dieppe, tack- ing constantly toward the west by means of the sail he had invented and using the guide-rope as a point of sup- port. Another time he went from Paris to Hamburg, remaining in the alr for twenty-four hours. But the most conclusive trial was the journey from Paris to Tours, which lasted thirty-four hours, during which there were three landings by which M. Varicle's son and Captain Mallet were set down en route. This last ascension gave ample proof of the efficacy of the “auto-lesteurs,” or automatic ballast-lighters, as anchors, another invention of M. Varicle’s which was suggested by the cone anchor and permits of a descent without loss of gas. Imagine a sort of large funnel pro- vided at its small end with a large sack of some stout goods. The fun- nel is allowed to trail on the ground, the edge scraping the surface and rak- ing up earth or snow, which passes into the sack. Presently the load thus col- lected attains sufficient weight to stop the progress of the balloon,.and by pulling in the rope the balloon can be brought back to earth. This “auto-lesteur,” which has given good results in France, is made of a new metal. as light as aluminum and as strong as steel, called “partinium,” after its inventor, M. Partin. The areonauts rely for success on other circumstances in addition to their tacking apparatus. In the first place, on the constancy of the winds in the region where they are going to operate, which, at the time they will make the ascent, blow regularly in a favorable direction; and fnally on the fact that they will travel at a short -distance above the land between the two chains ;f mountains which form the Chilkoot ass.