The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, January 9, 1898, Page 20

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

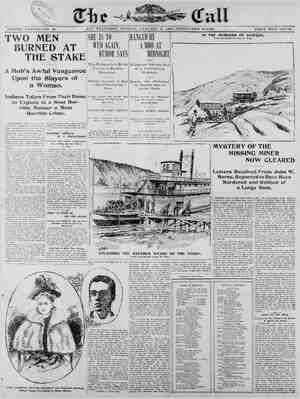

20 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JANUARY 9, 1898. NEW TERROR OF THE NA HEN she’s moving through the sea the best thing you can do is just to lash your- self to a stanchion and stay there. Nothing else is the least good.” Thus, the typical British tar, bronzed and bearded, comfortably stirring a bowl of steaming cocoa in the little triangular forecastle of the Virago, the little English torpedo catcher, that lay in the harbor last week, and now on her way to China via the north. Though the man was in all respects the regulation sallor, wearing a seaman gunner's badge, the forecastle was not at all shipshape and man-of-war style. The blue jacket looked strangely out of keeping with his surroundings. He should have been in the foretop of a full rigged ship of the old school, a post which was coveted by every true sailor, and only gained by the smarte: Instead of this, thanks to modern sci- ence, with its marvelous mechanical developments, the sailor was sitting in the hold of a vessel literally fillled with machinery. There were no spars to climb, no sails to furl or 7ropes to splice, none of the ordinary seamen- like duties to perform. The forecastle, though cozy enough, with a cheery lit- tle stove burning in the center, lacked the spacious orderliness of the mess deck of an old fashioned man-of-war. In fact, it had a distinctly mercantile look, with its small, round port holes and bare iron walls. Nothing but the bunks were missing, for the man ar sailor, unlike his brother in the merchant service, never uses a fixed bed place. And the rules of the service demand that a ham- mock shall be stowed away during the day, though, as there are no hammock nettings, it is 2 mystery how they man- £ge to put the beds out of the way on this peculiar ve 3 “Yousee, in this here craft,it's no use going on deck in bad weather,” the sallor went on, in the intervals be- tween sips. “Th nothing for a sailor to do, and if there was she kicks about so that you couldn’t do it. if T put my sea boots and oflskins on and started aft, by the e I reach the other end of her I'm black as a stoker just come off watch.” The sailor, it mayv be noted, supreme contempt for the upon him as quite an inferior being, has a though as a matter of fact the stoker is | the more necessary individual of the two. And on the Virago there are ac- tually more stokers than sailors, more engineers than officers. If you look around the boat you will easily see why this must be so. For the greater part of her length she is nothing but machinery, just little space at each end being left f commodation of officer: deck of bare {ron plates is absolutely devoid of ornament, the open iron rail- | ing offers no protection from wind and sea, the waves roll on board one side and off on the other just as they pl There are little round ho! coal chutes, all over the ¢ through these narrow openings must squeeze to get below. a you Even the commander has to go down a hole to his berth, and then shut the lid tightly after him for fear of being swamped. Not a pleasant craft to live on board of, even in the finest weather; vet the officers, with professional pride, speak most highly of her be- havior on the long voyage out from England. If she did take plenty of Why, | stoker; looks | water on deck it did no harm, and at any rate she passed demonstrating her sea-going ties. torpedo-boat, she differs from of her class in being able to hold the capaci- bined with phenomenal speed, rests the significance of this most recent freak of naval architecture. ter of the deck ard you find yourself in the heart of the ship. A narrow, | works of a blg watch; everything is | 80 delicate, so accurately fitted, so mutually dependent, one part the other. safely through | the worst weather off the Horn, thus | Even if she be but an enlarged | others | sea in all weathers, and in this, com- | Climb down another hole in the cen- | long room, simply packed with the | most complicated machinery. It looks | | indeed as if you had got inside the upon | | torpedo catchers is far in advance of all other torpedo boats. “We made over thirty-two knots on our trial trip,” the engineer went on.| “Vibration, of course, she shook just like that,” and he waved his arm to | and fro like a tree branch shaken by a gale. | “Still, you see, the hull is bullt in such an elastic way that the vibration | doesn’t matter, nor does it affect the engines; they run just as smoothly as clockwork. No racing nor heating. Look at that bearing; it’s been in use all the voyage.” He pointed to a big plece of shining | brass, which certainly showed no signs of wear. There are two sets of triple expansion engines, on elther side of the narrow passage, and the enthusiastic \ engineer assures me that every bearing Space at a rate equal to an ordinary train, short of the fast expresses. Herein lies the great value of these boats, which are destined to play a leading part in the naval warfare of the future. The torpedo-boat destroyer, or torpe- do-catcher, as she is more commonly though erroneously called, was devel- oped from the torpedo gunboat, a ves- sel designed to protect battle-ships from the insidious attacks of the wasp- like torpedo-boats. But the gunboat was found too slow for the service, and 80, some three years ago, the torpedo- catcher came into existence, the main idea being a sea-going vessel in which every other consideration should be sacrificed to that of speed. She was first put to a practical test during the British naval maneuvers of 1895, and every sea—some are in the Mediterra- nean, some on the Atlantic coast, others in China, and already there are two in Pacific waters. The European nations, though a long way behind, are following suit, and I wonder if the people of San Francisco, prosperous in their huge coastwise commerce, really realize the terrible power of the insignificant lit- tle vessel which lay so peacefully in the waters of the bay last week. Search the whole of the United States coast from Cape Ced to the Rio Grande, from Puget Sound to San Diego, and vou will not find a single sea-going vessel with anything like the same speed. In the event of a war with England the whole commerce of the Pacific Coast would be at the mercy of one of these little vessels. in the neighborhood of the engine- room, is quite sufficient to stop any merchant steamer, while thanks to the high explosives now in use, two or three shots would probably send her to the bottom. All the battle-ships, monitors, crui- sers or other ships of war which could be gathered together in San Francisco | harbor would be powerless against such a little vessel. A clean pair of heels; is the best of all defénses, and she would never stay to fight an enemy of superior force. Her mission would be to attack only unarmed commercial vessels. When a man-of-war with real guns came along she would sim- ply run away, and seek shelter in her own port, or with the fleet to which she was attached. Nelson, in the old days when his The above picture, while being purely imaginary, gives a fair idea of how this swift little vessel would look in the act of doing what she was built for. and overhaul 2ny merchant ship afloat. Being frovided with several good heavy guns as well as torpedoes she could soon wipe out a nation’s commerce. ward she has the appearance of a miniature whaleback, while aft her row of four smokestacks gives her a most unwarlike appearance. The vessel is 213 feet long, 21 feet 7 inches broad and 10 feet Ceep. She cuts the water like a knife and apparently without an effort. to be able to beat thirty knofs an hour. ore her nor leaves any in her wake. TORPEDO CATCHER VIRAGO IN PURSUIT O F AN OCEAN FLYER. DRAWN FROM A DESCRIPTION FURNISHED BY AN OFFICER OF THE VIRAGO. She carriss sixty-six m en all told. | She can glide through the water like a flash The Virago is a most peculiar looking craft. For- Her engines can develop 6oco horsepower under pressure and she is said Her displacement is 420 tons. She moves through the water without a ripple and raises no foam be- The engineer in charge pats the spot- less brass and steel of the cylinders lovingly. He has that affection for his machinery which is common to all men in whom the mechanical spirit is fully developed. “Steams well. T should say so. I've been with her since she was built at Laird’s yard in Birkenhead. Know Laird's?” Know Laird’s. I should think I did. and so does every American, for the story of the Alabama, and the famous shipbuilding firm which turned her out will never be forgotten. And just as the Alabama was far in advance of the cruisers of her day, so the new type of = connected with them is in equally good | the result may be gathered from the | From Esquimalt to San Francisco is l condition. They need to be, for when going at full speed the engines make 440 revolutions a minute, using steam at an initial pressure of 280 pounds. In two other compartments, sepa- rated by water-tight bulkheads, you will find the four water-tube boilers which take up the largest portion of the ship. Each boiler has its own smokestack, a low, raking affair, and they simply eat coal, so that if the boat travels at full speed she will ex- haust her supply of fuel in twenty- | four hours. But in that time she will have traveled 768 knots, or over 87 land miles. In fact, she cuts throug] | ent types of utterance of a distinguished naval of- | ficer who carefully watched the whole proceedings. “The impression lelt on my mind by the maneuv torpedo-boats are obso- lete, and that probably no more will be built. But I believe that boats of the size of the Destroyer will take their place in every navy, and that competi- tion as regards-the numbers owned will begin. England has the start.” Experience has justified the predic- tion, for Great Britain has already a hundred of the boats, either built or building. They are scattered over s was that all the pres- | but a distnce of 750 knots, which the | Virago, if pushed to it, could cover in a day. The fastest mall steamer which tra- verses the ocean would be helpless | against her, let alone the mere coast- ing boat. Even the record-breaking China would be easily overhauled by | the Virago, and there would be nothing for it to do but to surrender, or else go to the bottom. It is true that the armament of the Virago and her sisters is not heavy, | | she carries but one 12-pounder gun and | five 6-pounders. But a shell from even | the smallest of these weapons, planted | three-deckers swept the French from the Mediterranean, usea to speak of the frigates as the eyes of the fleet, and in his correspondence he constant- Iy complains of the lack of these handy vessels. But the very swiftest of fri- gates was merely a snail compared to the torpedo destroyer. Think what Nelson would have given to have had a vessel at his command which could scour seven or elght hundred miles of ocean in a day, keeping him constantly in touch with the doings of his en- emy. { This is a function which the new | craft is, above all other thin, | &S, espe- | cially fitted to perform, and it is safe LORD KELVIN'S OPINION OF THE “VORTEX" HENEVER one hears refer- ence made to such questions as the age of the solar sys- tem, the future of the =un, or the probable length of time that life has been possible on our globe, the name of Lord Kelvin is Bure to be mentioned as the authority for the opinion given. But for that matter, there is hardly any other question to which physical science has application, of which about the same thing may not be sald, for Lord | Kelvin’s interests and mental activiti appear to have no barriers short of the very limits of present human knowledge, while the original cast of his thought is such that almost any topic on which he touches is sure to reveal novel and unexpected relations, It was In reference to one of his spec- ulations, and one that easily takes rank among the foremost scientific imaginings of any age, that he very kindly granted an interview recently. This speculation at ever fascinating question of the ultimate nature of mat- | ter. When Lord Kelvin (Sir Willlam Thom- son as he was then) came forward with his very extraordinary vortex theory it was based upon mathematical tions of that other great physicist, Von Helmholtz, which took tangible form in Lord Kelvin's mind while he was watch- ing the activities of some curious little whirling rings of smoke In the alr, simi- | lar to those with which every tobacco smoker is familiar. Helmholtz had shown that such a vor- tex whirl once startsd in a frictionless medium must, theoreticaliy, #5 on for- ever. The vortex whirls of smoke in the air of course do not go on forever, be- cause their medium Is not frictionless; but Lord Kelvin observed that while they last they exhibit a similar stabllity, and though composed of mere wreaths of smoke, take upon themselves the proper- ties of solid bodles, in virtue of the mo- tion, just as a moving bicycle assumes the property of upright rigidity. And the thought came to him that if a vortex whirl were started in the ether, which physicists assume as penetrating space everywhere, such as an ether vortex (in- finitesimal in size, of course) would have the properties of a particle of what we term matter. came the vortex theory of matter. It is well within i bounds to say that this is the most | THE VORTEX fascinating and THEORV.] beautiful concep- tion of the ulti- mate nature matter that ever been propounded. world so regarded it, and took it up with acclaim, and made it all manner of other beautiful specula- tions. It had a simplicity that appealed to every philosophical mind; for it en- abled the thinker to reduce the entire universe to ether in motion. One had but to assume a few different | has kinds of vortices (the simplest of them | circular in form, but others perhaps va- riously convoluted) to account for the dif- ferent chemical and physical properties of the elementary bodies; and in the mind’s eye, one had in the ether that ul- timate, unique matter, the foundation substance of the universe. If then a man may take pride in his achievements, it would seem that the author of this theory might well be ex- cused if he held this child of his brain in a little more tender regard than any other of his mental offspring, and the astonishment of his interviewer may well be imagined when the vortex theory be- ing mentioned Lord Xelvin exclaimed caleula- | This thought expanded be- | of | The thinking | the foundation of | with all the emphasis that characterizes | his delivery: “The vortex theory is only a dream—it | is only a dream.” Was ever there a more as pronouncement than that? A ever | there finer test of the true greatness of | any A lesser man than Lord Kel- vin, having propounded a theory that found favor with the world would have dwelled and harped upon that theory all his life, twisting facts if need were to correspond with it, warping everything into shape to fit its needs. Such is the history of almost every theory, true or false. Yet here was the author of the | vortex theory treating that theory as if | it were a chance spark from his brain which might quite as well be allowed to die away and disappear! ounding | “ R R e s asked if he leaned I | toward the ac- | | HIS IDEA OF | ceptance of any | i GRAVITATION. | particular theory | | in explanation nf‘ sl e e S e i most universal and | familiar of phenomena, yet most inscrut- | able of mysteries. Before the advent of | the vortex theory the only plausible at- tempt to explain gravitation was | the Swiss philosopher, Le Sage, who sup- | posed that myriads of what he called | “ultramundane corpuscles” are | through space everywhere, and having the effect of pushing all bodies toward one another. But of late the thought of the vortex atom has suggested that grav- itation may be in fact what it seems, a | pull due to a sort of suction of the whirl- ing atoms. When asked whether this theory ap- pealed to him as it does to many think- ers of our time, or whether he preferred the rival theory of Le Sage, Lord Kelvin said, with even more than wonted em- | phasis: *No, no, no; I accept neither | theory; T accept no theory of gravitation. | Present science has no right to attempt | to explain gravitation. We know nothing about it; we simply know nothing about | g To convey by words the peculiar em- phasis and Intonation with which that verdict was pronounced would be im- | | deed, in any one who heard it to attempt an explanation of gravitation until such time as new data shall have come to our ald. A subject about the cause of which | (n the opinion of Lord Kelvin) we know | absolutely nothing is not likely to be | Muminated by any other person speaking from the basis of present knowledge. This, of course, is far from saying that | new data may not come to hand to-mor- row, Or next year, or next century, which will solve the problem. Lord Kelvin, | gifted with perénnial freshness of imagi- | nation, would be the last person to assert the finality of present knowledge. But it is certainly a salutary check upon the egotism of our time to be told that the | wisest ltving physicist, the man who has | been called the Newton of our age, knows as little of the cause why a stone tossed | into the alr falls back wo the earth, as the | boy who tosses the stone. { Another most in- specula- tion in which Lord teresting | | | | | THE HIGHEST [ Kelvin is Interest- | TEMPERATURE. | ed has reference to | | the absorbing | | question of the limits of temper- ature. As most people know nowadays, the condition we term heat is held by the physicist to be merely a “mode of motion,” a vibration or quiver among the particles of matter. The precise nature of this vibration cannot, of course, be Lord Kelvin was | that of | flying | possible. 1t would require hardihood, in- | e perfectly understood until the prec nature of the atoms of matter themselve is made clear. But Professor Dolbear has pointed out that if the vortex theory be true, then there must be pecullar limitations to the atom’s possibilities of vibration. A ring- shaped atom, for example, could only vi- —THE TORPEDO CHASER. to predict that in future no British fleet will {ake the sea unless accom- panied by several of these handy little vessels. When the fleet is at sea the boats will act as scouts, keeping the Admiral informed of everything that is happening on the ocean within a | radius of two or three hundred miles. It will become impossible for a hos- tile force to take the fleet unawares, and the commander who has thes; scouts at his service wiil be able to choose between fighting and running away. And this, under the conditions of modern naval warfare, is every- thing. The terribly destructive wea- pons with which all battleships are now armed rerder the annihilation ot the weaker force almost a certainty. No Admiral, in the future, will risk a battle unless he is certain the odds are with him, and the only way to in- sure this is to obtain beforehand acc rate information of the enemy's strength and movements If a port has to be blockaded or a hostile coast watched, the destroyers will prove equally invaluable. Expe- rience during the British naval ma- neuvers has shown that the small tor- pedo boats now in use can be easily chased and captured by the destroy- ers. The torpedo boat, it must be re- membered, has no offensive weapon €Xcept her torpedo, and this Is design- ed for use only against large vessels She could not use it, if she would, against the destroyer, and in the mean- time she has to face a heavy fire from the guns of a hoat far swifter than herself. There will be nothing for it but to turn and run back to port, and unless she has a long start, the swift- est. torpedo boat now known will not escape the murderous catcher. Practically, therefore, when the In- evitable great naval war comes, and circumstances render it desirable to invest an enemy's coast, two block- ades will have to be established. The outer line will consist of heavily ar- mored battle-ships or cruisers, watch- ing for the hostile fleet and ready to attack it should it attempt to put to sea. But within this squadron there will be an inner guard, a fringe of swiftly moving torpedo-boat des: ers, who will make sure that no h tile craft, however small, shall from the blockaded harbor. Or the merest chance, and at the g of all risks, could a torpedo-boat cape through this line, and in pra tice the attempt would probably ne be made. For one thing, if a torpedo-hoat suc- ceeded in creeping out it is tolerably certain that she would never suéceed in getting back. Whether her attack on the battle-ships were a success or a failure, the searchlights would dis- close her whereabouts, and the catch- ers would take her under their tender care. This one advance in construction has done more to revolutionize the condi- tions of naval warfare than any which has been made during recent years. The torpedo-boat, once a much- dreaded enemy, has received a blow from which its prestige will never re- cover. The destroyer, which herself carries torpedoes and can use them if necessary, has taken the place of the mosquito craft, and now it is only a question which nation can build the greatest number of them. Just at present the United States has none, but the naval authorities at Washington cannot long overlook the signs of the times, and once American ingenuity is set to work on the prohlem' ssue there is no knowing what develop- ments we may see in thls novel clas fighting ships. J. F. ROSE-SOLE of THEORY AND THE EARTH'S AGE. brate to the extent of becoming com- | pletely collapsed—just as a tuning fork | can only vibrate to the extent of bringing | its two prongs in contact. Corresponding | W““““w b2 . | married couple in the world. There }“Bve been several wel men reaching a greater age t Jacob Hiller has seen completed. Women who have lived longer than is nearly 106. But probably | other youth and maiden, marrying w | 20 and the latter 18, to pass together | brate their diamond wedding and still | of wedded life together after that. | ‘When the Hiltons were married the puny little nation. on the point o with England, the next with | brow-beaten by both. | power. “I'm 108 years old,” sald Mr. Hiller hln capacious arm chalr, In speaking i My birthday was the twentieth day { nodded toward Mrs. Hlller in her eas; ?s.um mext March. 1 was about 22 e’; ‘We were born at Jamestown, and lived there till we were ol UST outside of Elkton, Mich., lives perhaps the oldest 1 authenticated cases of han the 108 years which There have been many Mrs. Jacob Hiller, who it has nevi hen the former was life; to celebrate their go?den wedding and live on; to cele- (!:Foing t0 war one moment rance, Napoleon was at you see I'm pretty well started going on 109, She"’—here he But we were on the ot é:‘g_ck of Kingston, e 106 © o ®vueooo “Your children “We have had call on her.” er happened to any “Me?" said h years old before new ones since th and I can thread sleep as well as I 88 years of wedded © have thirteen years United States was a and insulted and the height of his blind and can’t read; but I dearly love t rrml:f the depths ot read to me. I sat lonesome -lmny here .: :5‘,‘.}'.' 2: o‘l s married life. times my grandchildren come lns read to me. And of last October; mn :l}:lenmnm sent to me for them to read, and I always keep ccocteeoee, e, c, “and seven of them are still alive. youngest is 58 years old. half a mile from here, wYou do not seem like so old a man, ?nd };‘nu,! Mhr-. Hille: ve kept house eighty- o old lady, “but I don't do such: worr feeble, pretty feeble. Cr YEARDS OLgb ! wow""".‘ are scattered?" eleven children,” replied Mr. Hiller, The oldest is 85 and the One of our daughters lives about and once In a while I walk over to said his visitor. with a shrill laugh.” “Why, 1 was 8§ I lost my first tooth, and I've cut two e:. nl e‘del never vfi)m glasses in n;ydme. eedle as well as you can. on’t used to, though." piped up the 0 much work now. I'm pretty I can’t walk much, and I'm 'most chalr opposite—"will “What kind of readin, = 2 & do you like best?" * g r? wl}en the war of Come THoly/ Spirit, Heavenly Dove, i er side, ?ou Kknow. ‘With all thy quickening wers; n Canada, Come shed abroad a Savior's love i And that shall quicken ours. | theory be true, th OLDEST MARRIED COUPLE IN THE WORLD. eccocoe, g ©ooe limitations would be placed u: atoms of any conceivable sh. says Professor Dolbear, if pon vortex | ape; hence, | the vortex ere must be an upper | limit of temperature. When the vortex | atom has reached its limit of vibration, hea} cannot become more excessive. Now, the physicists have long held that | there is a lower limit of temperature—a | so-called absolute zero—reached when the atom altogether ceases to vibrate, and the question has h.ghly interesting bearings, because it brings into consider- | ation no less a problem than the age of | the solar system. Astronomers and phy- | sicists are agreed that the sun, the earth, | and the other bodies of our system are | cooling globes, and the valculations of the | age of our system are based on the rate of loss of heat, an. estimate of which is derived from direct observation of the | sun In its present relatively cool state. | These estimates have been made most | carefully by Lord Kelvin himself, but | neither he nor any one else thought of taking into account the possibility that the original nebulous body which was ul- timately to become our solar system, may have had a limited temperature. Yet this possibility is a most important one, since | of course the rate of cooling of any body depends In part upon its degree of tem- perature. This question is one that appears to have had pecul- far Interest for Lord Kelvin. It even brought him almost to the point of a controversy at one time with the biologists (and his life has been singularly free from contro- versies), because he could only allow them 100,000,000 years for the existence of | life on the globe; and with the geologists because his calculations led him to be- lieve that the earth is solid to the core, and at least as rigid as steel, while they | stood out for a fluid interior. Hence It was to be expected that Pro- | fessor Dolbear’s suggestion. based as it is on one speculation of Lord Kelvin's, | and tending, if supported, to vitiate the | force of one of his important speculative | calculations, should at once interest the author of the vortex theory and the cal- | ! IS THE EARTH SOLID ? | culator of the earth’'s age. And so it did. i He either had not chanced to hear of the suggestion before, or else courteously felgned surprise over it. In either case, it unquestionably interested him intense- 1y; but when it came to the expression of an opinion as to the valldity of Professor | Dolbear’s conclusions, that was quite an- | other matter. ! “It is Interesting,” he sald, “most inter- | esting; but it is based solely upon the vortex theory, and the vortex theory, as I have sald, is quite unproved, and itself can prove nothing—nothing whatever. We must not heap theory on theory, dream upon dream. We must wait and see. If there be an upper limit of temperature, experiment may some time demonstrate it, but the vortex theory cannot prove it in advance, for the vortex theory is only | & dream. It can prove nothing.” | Thus once more did the vortex theory, which is the adopted darling of many a | scientific imagination of our day, receive the cold shoulder from its rightful sponsor. Of the same | tenor were the! great physicist's | ABSOLUTE comments on the | ZERO POINT. probable outcome of the experiments now being made with low tempera- has heard that Pro- tures. Every one fessor Dewar and other investigators have liquefied the gases, and even duced many of them to a solid condition, producing an almost unimaginable degree of cold. It having been shown that the same body changes from gaseous to liquid and from lquid to solid states, simply 'in virtue of changed temperature, the ques tion has naturally arisen as to what will happen when a body is reduced to a con- | dition in which the vibration of its atoms altogether ceases. The particles of a gas are so active that they fly asunder, re- duce their activity (that is to say, de- crease their temperature), and they move | freely over one another and assume the liquid condition, make them still more quiescent and a solid results. Will there, then, be another change of state when they are made absolutely quiescent at the absolute zero point? But, regarding this point also, Lord Kelvin's scientific caution asserted itself. “The experiments now being made are most interesting and most important,” but as to what they would show beyond the range of present experiment he de- | clared himself utterly unable to surmise. he said. If every “We must wait and see,” “We must walt and see!" | scientific worker would adopt that for his SCIENCE OF THE FUTURE. she the girLy maxim how much less there would be of crude speculation in the world? And so Lord Kel- vin's scientific cau- tion serves more | “almost than any- | thing else visible | about him to Im- press one with th greatness of hi ; mind. His freedom from prejudice is p: haps the very highest of mental endo ments. One feels glad that he answered just as he did about all these half-vision- ary and half-scientific speculations. But all the same there is pleasure and some- times profit in the occasional unleashing of the imagination, and the scientific world is to be congratulated that once upon a time Sir William Thomson per- mitted himself to dream the dream of the vortex atom. Nor is it at all certain that future generations will decide that it was “only a dream.” Certainly the main body of scientists of our day could by no means be persuaded to hold the vortex theory as lightly as it is heldbyits author. When genius dreams, they say, there is always a chance that it may “dream true.” De- spite Lord Kelvin's modest estimate, therefore, the vortex theory certainly will not be discarded until some better theory shall have come to take its place, and of that there is as yet no sign of promise. -—— HER OTHER NAME. A lady who wanted a servant so badly that she took one without a recommendation, or even an introduc- tion, happened one day to look into a book which belonged to the girl, and immediately thereafter went to her with some uneasiness expressed in her face. “Is this your book, Susie?” asked. “Yes'm.” “How is this taen? When you came you told me your name was Susie Stokes, but here in this book is the name ‘Bridget Lafferty.’” “It's all right, ma’am,” said “that’s me nondy-plume!” o Jihts B'x":xei first deaf-mute school in Great ritain was established at Edini in 1773, e