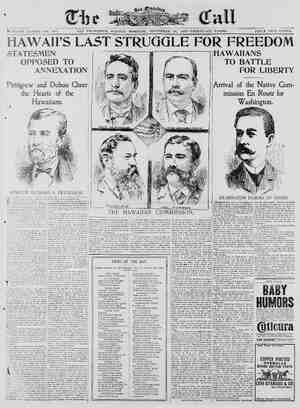

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 28, 1897, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

13. THE YEOMAN. He was clad and hood of green, peacoc 1 the yeoman, 10 the party, and 1s htand keen, | | 15.” THE DOCTOR OF PHY. 3IC. 1 the world he was there none him like | ak of physic and of surgery. | | In a good fellawe. | many & draught of wine he hadde | draw From Bordeaux ward, while that the char- | men sleep. 17. THE HABERDASHER. Clothed in a livery, Of a solemne and great fraternity. 18. THE MERCHANT. A merchant was there with a forked beard, In motley, and high on horse he sat, Upon his head a Flandrish beaver hat; His bootes clasped fair and fetisly, 19. THE SERGEANT-AT-LAW. Discreet he was, and of great reverence; He seemed such, his wordes were so wise, Justice he was full often at assize, For his science and for his high renown, Of fees and robes had he many a one, 20. THE CLERK OF OXENFORD. A clerk there was of Oxenford also { That unto logic hadde long ygo, | Asleane was bis horse as is a rake, And he was not right fat, I undertake. HARRY BAILEY, THE HOST. A seemly man our hoste was withal For to have been a marshal in a hall; A large man was he with eyen steep. 22. THE POET CHAUCER. 23. THE MANCIPLE (Purveyor to an Inn at Court). I have here in a gourd A draught of wine, yea of a ripe grape, | 21. And right anon ye shall see a good jape. This ¢ook shall drink thereo, if I may; On pain of death he will not say me nay. 24. THE COOK. A cook they hadnen with them for the | noue, | To boile chickens and the marrow-bones. seen them Har who sell nbs, shr men ldings, paver, and in unfrequ of their ruthless enemy. them in the wind and seen hold- nent of combs w at has caused you to put your hair ana smooth it m with a b aintaining a stolid on the streets, | pencils | who was a cripple and ‘‘done stitchin d Lite Led by Street Peddlers draped her bent old body to the ground. | She beld with bands invisible, somewhere | beneath the cloak, a string attached to a card bearing this: 'his poor old woman was born in 1820. | Feeble in health and sight she asks the | public to help her.” On her knees she held a cigar-box con- taining a few pencils as hard as her own | fate and their sphere of usefulness as lim- | ited as her own. She sold two for 5 cents and her proit | was 20 cents a dozen. She said she some- times made 30 cents a day. Her voice was indistinet and blurred, like a letier written with one of the hard | pencils she sold would have been, and she said she lived “"down yander’ dicating “yander” as some vague domain between west and northwest—with her daughter, “No; I don’t sell a-many pencils,” she *Folks ain’t a writin’ much these | | | ightless eyes to the moving plan ionless as the be: now b as so dead and unfinished looking. ve passed them at their posts until yon have grown to know n the ca: their necks | apter out of your owr life’s | , but you have never looked upon | ds abou e ordinary, voidable, times, ent of prog- to know or fortunes just & necessary., j t to the t thrown aside by , which moves are of the causes or the depths of th But ioned beyond 1s—you have not aims have they; how , how much on a windy her head and | corner | ed ith blind | e hard times; they ain’t got no money to waste a buyin’ stamps.” “Bornd? Where was I bornd? Oh, that's been a long time ago, don’t you | indicating the card with an air such dictionary. *‘Not when, but where; in what place ?" s been along time ago.” she re- plied apologetically and evasively as if she meant Yon must excuse me now, it has been so long ago and I was so very voung when it occurred that I really don’t know.” | But I guessed it was somewhere down east or at sea by the answer I received :0 the question, “*What do you live on?” i | | “Beans mostly,”” she answered, and | from her boudoir. | refrain about *They all took after me."” | | | being after her, chase her to some high | | place and jump her off. But she sang on | | | unmolested and almost unnoticed, the tin | ; empty depths, | ten cents. | *Ilive on Mission street ’long with an- | and speculating upon the number of pairs | of pantaloons it has taken one assumes when he refers you to the | | mumbled and shuddered as she drew her | cloak closer around her chin. | Another woman, who was also feeble of | sight, but not of such ancient date as the pencil-vender, was pumpiug an accordion | in the doorway of an empty store building on Market street. Her personal charms were added to by a pair of blue spectacles. and an odor of tobacco smoke clung around her. She said she was almost blind, was all | alone in the world and sang and played on the accordion to woo sweet charity Her instrament was | loud, but her voice was feeble and | varched and high pitched, like the voice | of one singing in afever; and the song she sang was a silly one, used and worn out by the circus clown years ago, with a But they didn’t. The truth is, no one took after her; but the wonder is that they did not, and, cup at her side looking up at the public with a great, unsatisfied longing in its | “Some days I make four bits, some days 1¢s a hard life—a mighty hard | life, other lady that cleans house. I pay her four bits a week fora room. My old man was a carpenter—got killed on a pile driver. I used to do sewin’ till my eyes failed me. Do? What am I a-goin’ to do? I'm a-goin’ back to my married son in Ellynoi as soon as I can git money enough saved up. I've been a-iryin’ the I last four years, butdon’t seem to git ahead | much. ILain’t begun to save up rit even, but I will some of these days when times gits better. | A few days later she was seen with a | bundle of red pencils. “I went into the pencil business be- cause it ain’t so hard on the voice,” she explained. I was sitting on the concrete coping on | the Kearny-street side of Portsmouth square one day, watching the other loafers | | | i to put the | polish on that same concrete coping when | I was approacbed by a one-armed man. tie held two red pencils in the hand acci- | dent had spar:d him and he sat down be- | side me and calied me “pardner.’” | “Now, pardner, I ain’t a goin’ to ask | you to give me a nickel, but can’tyou help | & man to get his dinner by taking two of i ’em for5cents? Judgin’ from your appear- | ance, I'd say you're an actor, an’ as I know H | people of that race is kind-hearted an’ | generous, I think you'll help a felier out. | | I know of a place down here on Kearny | | street where I can get a plate of stewan’a i dish of beans with a cup of coffee for 5 cents, but 1 ain’t got the 5 cents, an’ I ain’t had a bite to eat to-day, as I give my { last cent for lodgin’ last night.” | “And somebody gave you a drink?”’ | “Drink? Iswear Lain’t had no drink | | to-day.” | | “But your breath is evidence against | { you.” “What did you call it?” “Your breath gives you away.” | “Well, I'll tell you the truth; they give | me a drink at the lodging-house this | mornin’, but I ain’t et a bit all day.” “How much do I mgke? Two bits l | | business. | man can remembe some days, some days less. Ye; it is hard to Live on that, but by eating 5-cent meals an’ sleeping on the wharl some nights, an’ in a 10-cent bed oncein a while, I can manage to live. “Some other graft? I did have another 1 hed a metal polish an’ made atower of a hundred miles witn it, em’i how much do you suppose I made? A dollar. Just one dollar. I figgered it up how much 1'd make at that rate it T kep on a-goin’ t:!l I went around the earth, an’ it come to $250, so I give it up, I'd work if I could git work, but a one-armed man’s .otto have seven preachers at his buck before he can git a job. There ain’t many jobs a one-armed man can do, anyhow. Now you suggest some of the jobs you | think I could do.” “Messenger,” was the first suggestion. “Boys,” he said, ¥no use for a one- med man,” Run an elevator.” “There you air; boys agin.” **Bluck boots."” “Dagos; Dagos it; no show there.” “Porter?"’ “A porter's got to carry trunks upstairs; now could a one-armed man do that?"” ar got a monopoly of “You could clean windows and scrub.” | “Serub? ’Course I couid scrub. Yes, I could scrub; but tell me how in the name 0’ God I could wring out the mop?” ¢ could do any job where they’s noth- ing but waikin’ to be done. I can walk six mile an hour without an effort, an’ can make as high as eight. But say, air you goin’ to take two of ’em for five cents?" *'I bought some on the street the other | day, and they were so hard they wouldn’t make a mark.” “Now, thai’s it; some sells inferior goods. 1 know able-bodied men in this line that sells inferior zoods. What am I a-goin’ 1o do? Go back to Boston when 1 git money enough t0 go back iookin’ ade- cent. I wouldn’t go back lookin’ this way, an’ git the laugh from my parents an’ brothers an' sisters. I'm a barber by trade, but what could a one-armed man do at shavin’ and hair cuttin’? Air you goin’ to take a couple of 'em? Well, I pose I'll bave to walk, walk a mile before I sell one.”” But it was not an eight-mile-an-hour clip that he picked up as he went away. “It’s hard to starve, awful, awful hard, but it’s nip and tuck with starvation and me most of the time,” said an old blina man who was standing under the corner of a sheltering awning on Eddy street one rainy day last week. “Step in this way, a little closer to the wall; the rain is dropping off the awning onto your back,” I said. “I don’t mind the rain, it ain’t as bad as some things. You see, a b.iad man ain’t like other folks; he can’t see what's goin’ on around him, so all he can do 1s think, I stand here all day, a-thinkin’, and I can hear the wagons goin’ past and the car bells a-ringin’, and when I think how poor and useless and worn-out I am I feel /like goin’ out and standin’ on the car track and lettin’ one of them there electric cars bump up asin’ me and kil me. so many foolish things he's done in his lifetime when he ain’t got no eves to see what Lis neighbors 1s a-doin’, and he remembers ail the times that he let gocd chances slip by and all the money he's wasted, to come, down at iast to sellin’ penciis on the street, with- vut any home or family or friends. “I've been peggin’ along one way or another for twenty vears, since I lost my s ght—powder mill—and I ain’t never May have to | seen a cable or electric car, though I've been dolgin’’em and just barely gettin’ | missed by ’em sometimes for so long. But I've kep’ out of the county house and I’m goin’ to keep out of it unless business gets =0 bad I can’t make 20 cents a day— I can live on that—and if it does, then I’ll | stumble s me day and fal! down in front of the electric cars an’ let 'em make a| | good job of me. “You never tried starvin’, did you? Well, it's a mighty tough way to die. I | went four days once when I was sick without a bite toeat, an’ I guess I'd ’a’ died but another blind feller hunted me {up. Him and me lives together now, un’ we manage to'zit enough to eat, such as it s, but it ain’t the best. I ain’t tasted pie for seven years.” A little old fellow with a crafty face ana <hriveled hands had a side line of combs and shoe laces. | an’ she's crazy in the "sylum, an’ I wisht | I was along with her; she has a heap bst- ter time than Ido.” He spoke b tterly, as though he biamed his wife for possess- ing the faculty of going dait, which, by right, as being the heaa of the family, belonged to him. “But a man can’t go crazy 'lessen he’s built that way, can ’e? So I guess the bug house’s as far asI'll ever git.” I went with one to his home, his poor, commission-house. He was an old, old | man with palsied hands and rheumatic legs, who had been a sailor for many years. His house was-a corner of the cellar, partitioned off with whitewashed boards, and his grounds were the dark, rat-haunted recesses of the musty cellar; his ornamental shrubs were the stems of old cabbage and the trimmings of celery heaped and scattered about. “Hoss throwed me off and hurt the His furniture was 2 bank against the | spine of mv back,” he said; ‘I ain’t been | wall and a small oil-stove, a box for a | able to work since. chair and another one, painted blue and “No, 1 ain’t got no family, 'cept a wife | with closed and padlocked lid, with the | bare, lonely home in a cellar beneath a | words, “Thomas Flynn, Relfast,”’ painted across the enJ. There was no means of ventilation, and the smell ot onions and cabbage and potatoes oozed down from the floor above. the smell of decaying out- casts of the vegetadle world in the cellar went up, the two forces met and mingled in the apartment ot Thomus Flynn of Belfast, and Thomas Flynn contributed to the assembled odors by smoking the ends of outcast cigars in a pive made of & brass oil-cup, from some outcast engine, by the hand of Thomas Flynn. | So in these old battered human builde | ings some litile thing of human interest, some rusted link connecting them to the world of yesterday, will be found on look- ing near, showing that however far ree moved from the walks of usefulness they are to-day, they have tried at some time and failed, and the world has grown up about them and crowded them into the unused and forgotten crannies, and like | the old buildings, with no tenant and no landlord interested in their welfare, no one knows when they fall. G. W. O. that a people who were born and raised In the promised land, and who, from time immemorial, have lived in Palestine among scenes that are often mentioned in Holy Scripture, should have journeyed so far as California, which, they say, is “just like home in its climate, soil and produc- | tions.” In their own land they are governed by customs and laws which have been hand-d down from generation to genera- | tion. A patriarchal system controls | both family and tribe. In the family the | eidest is the head, without whose consent | and counsel nothing can be done. The head of the Armenians in this city i is Sclomon Raby, who was educated in | the scnools of the American missionaries | in Palestine, and is a man of great intelli- gence and influence. He speaks and writes the English, Turk- ish, Armenian, Greek and Hebrew lan- | guages. He hasa wife and several chil- | cren, one a daughter whose beauty and grace are remarkable. Dressed as an American btelle this Armenian beauty would excite admiration anywhere. The | Armenians are a very religious people and their church is claimed to be the | oldest 1n existence, founded by one of the aposties who journeved to their land at the headwaters of the river Euphrates and converted the nation to Christianity. The ceremonies instituted by the apostles | are still observed, though numbers of them | have fallen away from the orthodox be- | lief and joined the Roman Catholic and | Greek churcnes. St. Putrick’s Church has | | | & Down on Jessie, Minna and Natoma streets, just off Mission, and only a block away from the Palace Hotel, lives a most interesting colony, composed en- tirely of Armenians, numbering altogether 150 men, women and children in about | equal proportions. Though the locality has ceased to be desirabls to the better class of tenants, and the buildings show evidences of having | seen better days, yet the Armenians, with the instinct of strangers in a strange land to cluster together, have formed what is known as the Armenian Quarter, a place enticely distinct and where a strange language and unfamiliar scenes a large number of Armenians in its con- gregation and many attend the Greek cathedral on Powell street. Those who are strictly orthodox are at- tendants out of the Mission Chapel of the Good Samaritan on Folsom street and are very devout and attentive. The Rev. Ed- ward Morgan, the assistant priest at the mission, is greatly interested in these peo- ple and is much beloved by them. There are people of different tribal af- filiations among the colony, who retain their distinctiv: customs even under American influences. Physically the Armeniansare a strong and handsome race, and remarkably bright. Their eyes are fine. Thechildren, who numberabout attract the passer-by. It appearssingular one-third the total colony, are all being San Francisco's Armenian Colony educated at the public schools, when of suitable age, and are spoken well of by their teachers as obedient and intelligent. The ease with which they acquire the language is said to be unexampled. Ac- cording to the local patriarch, the Ar- menians of California have all but one |aim and purpose—to acquire and own & ranch. There are about 250 in the State, 1 and about one-fifth now own farms. Those Living in the city turn theiz hands to al- z00st any occupation, mostly peddling jewelry or small wares, which all engage in, from the oldest to the youngest. Some of the young men are waiters. All are ine dustrious and saving. no notice of the cap- arrived at Auckland 1 met M 1d she asked me how you e I answered her truthfa s far as 1 I told her that you were keeping | all siore here, but that times w bad, and I supposed you cou rd to send for her just yet. iid mv best to lie gracef re in’t . bu me, whispered or somehow I don’t think she believed pe somebody had h aroused her suspi ‘I'm tired of beir d if the captain 1s poor it's my duty to be th I don't care what any one g to bim. I'vesaved up a | there’s my watch and | id earrings he gave me left on that last cruise. ttle bit of furniture we’ got comething; so I think I can | v together. | as a sailor’s wife the com- nave my passage ata haps pounds, and fercn manage to scrape enough mon; And, I dares pan 1 Jet eduction.” I did my best to persuade her to give | » the id ut it was no use. When we turned to the port a fortnignt later she eon board with her three children told me how she had managed to t enough money to pey for a sec- saloon passage for them all. She’s a | clever woman, there’s no doubt about 1 added (he purser, who I could see was rather inclined 1o iake the injured wife's part. “I felt the same way myself, ana the captain found no sympathy in my eyes when he looked up and moaned in a help- less sort of way: ‘What in God’s name onid i S T = RND BY J. F. ROS ) E- SOLEY. am [ 1o do, Wiliiams? Speak. Can’t you belp a man ‘I believe that I almost cespised him then for his lack of maniiness, but he was my friend, 1 had just been drinking his og, and I must do what 1 could to aid vou really married to this I asked. ' he replied, ‘we were married enough beafore a clergyman in Auck- land fifteen years ago. *“*“Then Mary’s not your wife at all.’ “‘No, God help me,” said the captain, now quite broken down. 1 thought a minute. ‘There’s only one way out of 1t as I can see,” I said at last. ‘Mary must g0, and vou must be ready, decks cleared and hammocks stowed, to welcome your while wiie to your home.’ “*{t’s hard lines,' groaned the broken- down skipper. ‘Puor Mary and the baby.” i u siould have thought of that be- fore,” I sternly replied. ‘You've got o do the right thing now for once. And you'd better hurry.” ‘At iast we roused him from his stupor, and the purser went off to attend to his business, leaving me alone to manage things with the captain. “We 10ld Mary as well as we could what had happened. She cried bitteriy, for she had always believed herself to be really married to the captain; but at last she went off with bher baby to her mother’s house at Matautn, the other end of the town. To console her we told her that the white lady had only come to staya few weeks, and when the visit was over she might return to her home and her busband. I don’t know how many lies I somehow. “Mary had hardly been gone five min- utes, and we were busy turning the house upside down and removing all traces of her presence, when we saw another boat pulling through the surf to the shore. The captain took up his telescope. ‘There she comes, Williams,” he cried, ap- vealingly. ‘Don’t go just yet. Stand by and see me through with the old woman.’ *Of course 1 stayed, for, it must be con. fessed, 1 was not a little curious to wit- ness what would happen. “A tall, middle-aged lady, well dressed and still handsome, stepped out of the boat, followed by a fine boy about 12 and two vounger girls. They were all neatly clothed and bore evidence of the careful attention of a well-bred mother. * ‘Here's vour pa,’ eried the lady, joy- fully, as the lit le procession rushsd into the store, and she threw her weil-devel- oped fizure into the romewhat reiuctant arms of the captain. But he had to keep upappearances, and perhaps his Leart soft- enea somewhat toward his ill-used wife, for presently they were kissing and hug- ging like a pair of lovers. **‘Dear me, Jack,’ she said, looking round at the disorderly ‘parlor, ‘what a miserable bachelor’s home you have got, to be sure. It’s quite evident you wanta woman's care, you dear old stupid darling,’ and she kissed him again and again. *0id Trenton seemed to regain confi- dence under this treatment. ‘Yes, my dear,” he said, ‘you see we have 1o rough it here, and these brown servants have no idea of tidiness.” “ ‘I'should think not,’ she said, looking around. ‘Why, here’s a great hole in the tablecloth and a pile of old newspapers on the sofa, and, dear me, why here’s an empty gin bottle on the writing-desk, and all the tumblers are dirty, and there are sticky marks everywhere, and ‘tobacco ashes on the mats, and—and—' She shook her fist at me playfully, as if I were the cause of her husband’s bad habits. “It bad always been poor Mary’s pride to keep her home as neat as a new pin, and certainly I never saw a cleaner, better managed house than Trenton’s under her care. Butin the few minutes’ breathing space uliowed us the captain and I had managed to create a surprising smount of disorder, and the result from our point of view was bighly satisfactory. told that day, I am sure, but you see things had got to be straightened up “So I left the skipper to settle down to a third edition of married life, and, for nl week or two, as far as I could see, every- thing went on smoothly. “But idle tongues will talk, and Apia is a famous place for gossip, and conse- quently it was not long before Mrs. Tren- ton the first began to hear something of Mrs. Trenton the second. I was not present at the conjugal scene which followed, but the captain, for the rest of the day, looked very much ashamed of himself. But I must say that the white lady, though she had been so badly used, behaved like a trump over the whole affair. “The next morning she came to me with a troubled, weary look on her hand- some face. ‘Williams,’ she said, for by this time she had quite accepted me as a friend of the family, ‘I want you to help me. Iam in ad flicuit position.’ *‘Anything I can do, I am sure,’ I re- plied sympathetically, for 1 was really sorry for the woman, ana besides, any one could sece she was a real lady and much tvo goed for old Trenton. ** ‘I believe you, Williams,” she answered, softly, laving ber hand on my arm. ‘Do vou know this girl Mary?” and the faint- est trace of a blush brightened her pale cheek at the mention of the name. “I knew what it must have cost her even to speak of, much less recognize the position of her rival, and I only answered “Yes,” not b-ing able to think of anything better to say. I am all right when it conues to telling a yarn straight on end to a friend like you, for instance, but when a lady gets asking me questions of this kind my tongue loses itself somehow. *‘Tell me all about her,” demanded Mrs. Trenton. *1 told her as well as I could how Mary had come of a respectable, half-caste family, and how every one thought she was really the captain’s wife, and how lucky she had been considered to 1 ke such & good match. And when I told her about the baby, and how fond they both had been of it, I think her heart softened. “‘Take me to her,” was all she said. #+But,’” I stammered, ‘she’s in a native house at Matautu. It isn’t fit for you to go there: it isn’t, really.” “ “My husband’s house was fit for her be- fore Icame,’ she replied in her stately way. ‘I'ake me to her at once.’ *“There was nothing for it but to obey. She was not in a mood {o be thwarted. 80 we walked off along the beach road, past all the stores and hotels, Mrs. Tren- ton holding ber head high and stepping defiantly, as if nevera trace of shame could touch her, though it was sucha miserable business. It nad been the talk of Apia since she landed, and the gossips marveled what would come next when they saw her on tue way to Mary's new home. “We crossed ibe Vaisinango River, and passed through Matautu, where the roads are shaded with trees and there are fewer people to meet, and at last, at the far end of the suburb, in a wretched native house, we found Mary. “‘She was squatting on a mat, clothed only in a dirty white frock, the remnant oi her former finery, out the baby, I noticed was as well dressed and as fine as ever. And when the little chap saw the fine lady enter the house he lifted up his little arms and cooed. “Ican’t tell exactly how it happened, for somehcw my own eyes were rather dim at the time, but the next moment Mrs. Trenton was down on the mat be- side Mary, and the two women were hugging and kissing and weepiug to- gether over the baby, who stuck his little | fat fist in his mouth and roared in sym- pathy. “‘When the storm had somewhat sub- sided the two had a long and confidential cenversation. I kept, of course, at a respectful distance, but Mary told me all about it afierward. The kind lady, as she called Mrs. Trenton—jor poor Mary was not a bit jealous—had asked her many questions with regard to her married life with the captain, and had in- quired particularly about her prospects for the future. “Mary, completelely subdued by this good woman’s influence, opened her little heart, and ‘sobbing as she lay in the other one’s arms, confessed the blackness of her despair. Theie was nothing before her but death, or to come down to the na- tive level. Her father was dead, and her mother, as many white men’s widows do, had married a Samoan, and gone back to her ori, inal habits of life. Mary did not mind for nerself, but she hated the idea of her son, who was such a fine little fellow with good white blood in him, growing up a Samoan. “And Mrs. Trenton, though she didn’t know much of native ways, glanced round the shabby disorderly house at the naked children playing in the dust outside and shuddered herself at the idea. After all the boy was her children’s brother and her husband’s flesh and blood, and notwith- standing the words of Scripture, his father’s sin should not be visited upon him. “Then it turned out that Mary hada chance of getting married again to a re- spectable white man, a shipwright in the employ of the German firm, who had courted her with some show of success until the captain came on the scene. But the shipwright, though he would ac- cept a discarded wife, would not accept the baby, and Mary had absolutely re- fused to give up her child. **But you would let me have him, wouldn’t you?' asked Mrs, Trenton. “‘Yes, ves, dear,’ cried Mary, eagerly, “for I know he would be well brought up, as a papalangi, and not as a Samoan. And some day be will grow to be a great man, I am sure he will. See how clever he is already,” and the fond mother hugged the child to her breast. Tken, w one long parting kiss, she placed him tenderly in the open arms of her visitor. “So it was settled. I often think of that woman, I can tell you, walking back through Apia town—and the beach road was full of gaping people—as proud and erect as ever, carrving the Jittle baby, o that all the world might see. And when we reached the store she laid the chiid in the surprised captain’s arms. ‘I have brought your son back,” was all she said. She was a grand woman, and the old trader paused for a while as if to give due effect to his words. “*‘And did Mary marry wright?’ I asked. “Of course, and lived happily ever after- ward, I suppose, [ never took any fur- her interest in her. Mrs. Trenton made the captain settle a bit of land and a col- tage on her, so that she had a good start in bher married i But the boy was brought up by Mrs. Trenton asone of her own children. Never a scrap of difference did she make, <o far as I could sce. “And when the captain died and the family went back to the colonies she ap- prenticed the lad to a boatbuilder, so that he might have a good trade at his fin- gers’ ends when he grew up. She still writes him and sends him little presents, for, poor soul, she is not very well off and cannot afford to do more, “This is how Mildmay’s boy, as we all the ship- call him here, spaaks such good English and is altogether so white in his ways. Stop and haye some lunch. *No, thanks; I've got a lot to think over this afternoon.” So I had. ‘When the old trader got on tne subject of women, brown or white, he was always garrulous, and therefore I was not sur- prised on my next visit a few days later to find him refer to the subject of his own accord. ““Women is women,” he said senten- tiously, “‘all the world over, and whether they be brown or white makes but little difference. I to!d you lust week about a white woman,old Captaian Trenton’s wife, who was as good as gold.” “She was an exceptionally kind-hearted woman,” 1 interposed thoughtfully. *Per- haps it's the result of the tropical influ- ence; bat very few of her sex in another country would have acted in the same way.” “That’s so,” assented the trader. “May- be it's the latitude, or maybe it’s the example of patience and forgiveness set by the natives themselves, for I've known brown-skinned Samoan women act quite as generously, and with far less cause, “What,” I exclaimed, in surprise, for the qualities mentioned were hardly in keeping with the estimate which, based on a merely superificial knowledze, I had formed of the female native character. “You need not look so doubtful about it, it's quite true. The Samoan womun is like every other woman, when she is bad she is a regular out and outer, but when she is good, why there’s no limit to the extent of her virtues. And white men in this country are not always, as you know, immaculate husbands. There was one native woman, I remember, who for years lived alone in Apia, with no one but a little half-caste boy for company. There’s asad story about her, if you like to hear Ot course,”” I assented, ‘‘zo ahead.’” [To be continued.] The Difference. When first he went to college A sheepskin was his quest, But now that he’s a senior, A pigskin suits him best. e enae oS The philosopher who telis us to aim higher than the mark would doubtless kiss a girl on the nose,