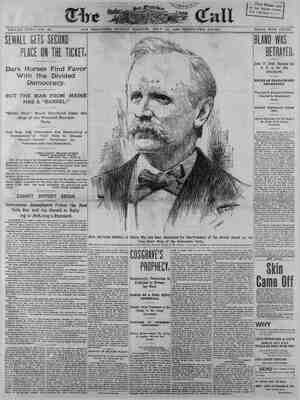

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, July 12, 1896, Page 18

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Passenger (o0 a Powell- street car, rising politely)— Excuse me, mum, but do you believe in woman's rights ? New Woman—DMost cer- tainly, I do. Passenger(resuming seat) —Oh, well, then stand up for them.—Wasp. There is no carica- ture without a truth behind it; none from which truth cannot learn a lesson; no la- bored joke in a comic paper but has a point if you look deep for it. Woman's rights and woman’s wrongs are so thoroughly discussed just now that it would seem she has none of the rights she ought to have and ali the wrongs she ougnt not to have. I have n.ofiud a few of my own and my sisters’ {nllng?. We take rights we have no right to. Sometimes it makes me so out of patience 1 wish I were something else than a woman—not & man thougn. I am like Topsy. That standing up in & car, now. Why shouldn't she? She claims and ‘proves ber claims to strength, and why should skirts make a man give up his seat to her, except in cases where he would do the same for another man? I never want a man o give me his place in & car orelsewhere. I have no right to it. There is nothing makes me feel my downtrodden condition so keenly as to be compelled to take the place of some ola gentleman not one-half as able to stand, but whose old-school politeness makes 1t impossible for him to sit while one of the “*fair sex’’ stands. When a woman with a baby comesin every one, man and woman alike, isin duty bound to rise and insist upon making her comfortable. We are not giving place to the woman, but to the mother and child. We would do the same for a man witha like burden, or we would offer to hoid the baby., The weary woman with seven | bundles and a trail of children like a flight | of steps—well, ehe has no real right to my seat or my brother’s, but I would give her mine gladly. 1 am so glad not to be in her place that I would stand half a day just for the pleas- ure of seeing her for once at rest. { The woman with a erutch or a eane it is needless to mention. California mep stumble over each other to help her, and the tired conductor’s cross face grows all _ Women's ights That I-\rg Very Doubtful Rights what was not my right, and I bad to stand on the step with pne arm around a post. The car swayed and flew, my skirt caught a picturesque border of thistledown and foxtail, my cheeks tingled in tbe wind, it was glorious. I know all would not like a ride of the kind; still, if you object to thistles in your dress, think of the anguish that is wring- ing the heart of the polite young man &s the foxtail enters his soul by way of his dearest Sunday trousers. [ While 1 am preaching’ about cars, there is a secondly, my sisters. How many peo- ple is one woman equal to? If we areeach equal to one, we have no rightto more space than one would naturally occupy. Big sleeves are lovely. We all dread the day when fashion shall decree that our arms shall look like sausages, and it does hurt to have them crushed, to come out of a crowd with our pride flat. Isitthe crowd’s fault? No, ma’am. You and I have each the right to one woman’s room and no more. If, with big sleeves and voluminous skirts we take the space of three, we must be good naturea when we find ourselves flat- tened sidewise to cur natural width. Did you ever notice the glare of displeas- ure as a man settles into what he thinks is an empty seat between two ladies? The seat is yecant, to be sure, but aseach shoulder of the man touches that next to him, cr-ra-ack goes fiber chamois, like the sack in which Little Claus kept his con- juror. The man looks embarrassed or annoyed, while tbe owners of the pneumatic sleeves send hghtning from both sides. Iu is funny. They have no right to the extra space, and he has. The same if the folds of the full and heavy skirts billow out over tahe floor and the last passenger takes his stand thereon. If I were he I'd delight to walk all over it—with nails in my shoes. gentleness again. I think nowhere are all classes more tender to bodily affliction than in our home city. The old lady with the snowy puffs and the placid far look in her eyes, as if she had passed all the puzzles of life and could see something beyond, is willing to stand, and protests with her gentle hand and soft voice against putting you to any inconvenience. You would no more sit and see her swaying from a strap— why you feel like standing in her presence any- way. There is often a pe- caliar look in a girl’s eye when she has to stand that, were I a man, would effectu- ally put to flight any chivalric purpose. It is the same because- I-am-a-woman look I have spoken of be- fore. I notice that girl usually stands unless there is an old man in the car, and in my secret heart I rejoice. Then there is the comfortably circum- stanced shopper, on her way home just at the season when workingmen are fill- ing the car. She not only has no right to expect one of these men to give up his place to her, but she has no rightto accept TWO STRIKING PORTRAITS, it if it be offered. Maybe she is fatigued from her after- noon’s standing and choosing; perhaps the thought of jolting along fifteen or twenty minutes hanging to a strap is not a pleasant one. Justice is justice, and you know how often we quote of late that God created all of us free and equal. That shabby man with a tin pail between his feet is tired too; he was first in the car, paid for his place and has a right to it. The woman with adog in her arms has no right to a seat, even when no one else ‘wants it. I do not like to stand in a car. I do not enjoy sitting in one, either. If I cannot sit on the outside I like to stand there, and often I would rather stand than sit. Be- cause of the bad habitsof my sex I have to explain this laboriously every time I stand. The other evening going out Sutter street after a long day’s work sitting in one cnair my heart beat high with hope. The car was jammed. The only possible place for me was standing-room on the front plat- form with two men. What a good breath of damp air I would get, how my tired ::ck would relax and how hungry I would But I had forgotten who I was. The conductor came as quickly as he could, and with s glance through the door he gaid, *I will make room for you to stand inside, Miss.” X “Oh, don’t,”” I pleaded; ‘‘it is so stuffy. 1 would rather stand here.” “You are quite right,'’ spoke up one of the men; “the air in there is enough to XilL" Bo I escaped for the time. [N. B. S8houd 1 bave been offended atthe man's speech ?] At the next corner two women got off.. Two men went to sit down. “Lady on the platform ! announced the condiictor, and one man hung himself up again. The lady on the platform looked away with a stony face, buc no use. The polite man of fares was bound to do his duty. “Room inside, Miss.”” *I would rather stay out here if you do not mind.” I think t must have gone in willy-nilly, only a man got off the dummy and waved me to his place. Seeing that the earth was disturbed and the heavens shaken by rea- son of my obstinacy, J sat. I didn’t have any right tothe place, and [ didn’t want it. The most enjoyable ride I ever took (on a car) was across the bay going to Blair Park., It is a fine ride anyway, through fields and over hills, and I got on a car full of women and children. There was no one to say me nay, 8o man to give me © . Leaving thecarand following the sleeves and the skirt of many yards to their desti- nation, we see them still usurpers, taking other folks’ ground and other folks' view with & coolness that belongs everywhere to pure selfishness. In the sheater thé prospect of silk and the topping of feathers may be very won- derful to the little man sitting behind, but it is not what he paid to see. Nowhere and never can one garment cause agony to so many people as a full skirt going’downstairs with a crowd. Now doesn’t that bring to you a picture of an unconscious madam, dignity inevery movement, sweeping down the stairs with yards and yards and yards of good strong cloth wiping the dust from three, no, four steps, rustling now to one side and then the other, while a nearly frantic man comes after, pushed from behind, and with almost superbuman effort trying to keep off the grass? He steps gingerly down, pushing the mass with his toe to make room for his foot—one step; her majesty sweeps on, the billows fall and leave a space clear—two steps; she steps again, the skirt starts, the man starts, and the woman pauses to nod to ong in the crowd; the skirt pauses too, and the man is standing on it with tears of distress in his eyes; he hopsto oneside, treading on three different feet, bringing down as many anathemas on his uniucky head—three steps; the skirt moves on— four steps; in his dizzy eyes the mass of clotn is a hideous mass of snakes and they are drawing him with resistiess power to tread on them and die; the people behind push, and a voice whose owner sees the space ahead grumbles that there is plenty of room for him to go on, and they press harder—five steps. Alas, alas, the eddy- ing billows abead and the pushing crowd behind are too much! At the sixth step he goes plump with both feet on the skirt just as madam takes a step. There isa tearing sound that seems to him the crack of doom, he sees a pair of angry eyes, hears a-sharp voice call him awkward and stupid, stammers ana apologizes, and is so glad to get out into the darkness and lay his hot head against a lamppost. The woman nad no right to more than one step. I have walked downstairs, my skirts heid close—it is easy enough—and pushed before me all the way another woman'’s flowing garment. If my shoes were muddy 1 suppose I was sorry. Once I was coming down the boat steps with 8 man who thinks it a disgrace to be brusque to & woman. He patiently kept off & skirt, until at !ast he turned to me with a question, put his foot on the cloth and tore a piece out. He started for the owner to apologize, I couid not stand it. With my hand on bis arm I expostulat- ed. *“Don’t you ex- cuse yourself! Don’t dare to apologizel She owes you an apol- ogy instead ! 8he had no right to the whole stairway ! "The wom- an turned, heard and saw. She came back and begged pardon. I forgave her. There is one right which is no right our sisters are fond of taking—''keeping a seat for my friend.” - In a crowded hall where no seats are re- served, where ‘often they are not even paid for, my lady will calmly put her fan in the next chair and for an' hour tell the people, men ana woman who have & right to that chair, that she is keeping it fora friend. And ghe insists upon keeping it, 100, turning a deafear and'a blank face upon demands for the seat and remarks about her right toit. When “my friend’’ comes she rustles into the empty place with an air of proprietorship most engag- ing—if you are not the one defrauded of the seat. If 1 were an artist I would draw that woman in the likeness of a nice clean pig. 1 saw her last week biackmail 8 man out of his chairina way wonderful to see. Her friena came up to her, late as usval, and she eaid: *I tried to keep your seat, dear, but this gentleman took it and I didn’s like to ask him to give itup. I'm 80 sorry you have to stand.” The man left his chair and stood by me, soliloquizing, and I said for him to hear, “The selfish you have with you always.” Itelt sorry that the man should have brought home to him so forcibly the weak side of my sisters, and was glad when, an hout later, & black glove was laid on mine, and a quiet voice said, ‘‘Now, you take this chair for tne rest of the time and iet THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JULY 12, 1896. Wild Lieap of a Daring Wheelman A few nights ago the chains which held the Piedmont to the pier in Ban Francisco had been released with the customary clank, the deck hands had pushed up the apron attached to the pier which bridges the gap between the pier and the boat’s deck, the signal had been given for the wheels to revolve and already the paddles were churning up the water under the boat into a resemblance to soapsuds; the thrill of movement was already ex- perienced and the people who habitnally frequent the lower deck while crossing the bay were amusing themselyesin customary fashion, smoking, gossiping and preparing to eniff the cool air as soon as the boat passed out beyond the piles and .into the ship channel. : : Suddenly there came into view a start- ling apparition. Down the wharf, clad in sweaters and bicycle garb, sped an impet- uous wheelman straight for the fleeing boat. The spokes of his bicycle wheels were invisible. His feet went up and down with regularity and great speed. At once there was a feeling of apprehension on tbe ferry-boat, and warning shouts in- stinctively were uttered. The scorcher paused not nor hesitated. The boat was moving, but the bicycle easily outclassed it by many degrees as a racer. Just as the clear water was about to sHow between the edge of the apron and the deck of the ferry-boat the bicycler leaped from his bicycle with the speed of thought, seized the machine and boldly jumped toward the boat. He was cool as well as nervy, and his wheel was not permitted to strike the deck with a perceptible jar. Then the men breathed easier and women specta- | tors laughed hysterically. The bold rider took a fearful chance. LONDON, Exa., June 24 —To pass through a room con- taining a number of pictures means gener- ally to carry away an impression as indis- tinet as the facesofa crowd in the street. Sometimes a single picture rivets the at- tention, either through some strong characteristit charm, some particularly . striking defect or merely through the accident of a vivid light. There was a small, very cheice loan ex- hibition to be seen for tive days at Camp- den House, and a single portrait made the figures in very many of the modern pictures of eyening. it is only fair to add that this is essen- tially a personal experience, People col- lected in groups before the great canvas by Luke Fildes, called ‘The Doctor'’; looked in solemn respect at Paul Dela- roche’s great tragedy of Marie Antoinette going to ner execution; at Gainsboroughs and Romneys and Sir Joshua Reynolds; sighed pensively before Sir Frederick Leighton’s great decorative illustration and wept tears of joy before anything, new or old, bad or good, painted by the present president of the Royal Academy, Sir John Millais. And hanging in the shadow of a great window, with the un- shaded light blinding the eyes, was the exquisite portrait of a little girl, Miss Cicely Alexander, by that prince of jokers and king of painters, James McNeil Whis- tler. And this little white rose bloomed almost unnoticed 1n the corner. To live in London is to pass from expe- rience to experience. Nowhere in the world, not in gay Paris itself, is the oppor- tunity for enjoyment so rich or so varied. | Besides the great picture shows at Bur- lington House and the new gallery there have been three swell exhibitions opened land closed within one week, and each " ONE OF WOM ol (i (v e g m gt AN'S RIGHTS THAT MA me stand.” I took the little stranger’s place, glancing to see if the ousted man saw the other side. He did. ‘We have no right t6 go to a piace where people have assembled to hear a certain thing and regale those apout us with pri- vate affairs. Iwent once to hear Congressman Maguire talk single-tax. Like the man who aston- ished the Circumlocution Office, I wanted to know, you know. I didn’t know more about single-tax after, but such charming tales I heard of the last illness of the woman behind me. And, lastly, of my younger sisters, They, too, take more than belongs to them. The schoolgirl tyrannizes over a male teacher in a way that is pitiless. She does and says what he would never en- dure from a boy, and does it with con- sclous impunity because she isa girl. If once in & way a teacher lets discipline overrule sex consideration what a wail arises! The brute! to punish a girl. ‘Why, a girl without doing enough to hang a complaint .on can nag the life nearly out of a teacher. I have pitied a young instructor, only a boy himself, in the tolls of a cruel girl. I have said to him, “If you show her.she is subject to the same laws and the samé penalties as her brother she will cease.” 1 don’t exactiy like to tell the rest of it. He took my advice and lost his position. They said, *‘Of course, if it had been a boy it would have different.”, Thete is no such and “of course.” p The average girl on & wheel takes her share of the road and asmuch more as she wants. She expects the boys to keep from getting in her way and to keep from getting where she will be in their way. I know. Iheard a man's opinion of me when I nearly ran him down before I learned to manage my wheel and I said to myself, “My friend, them’s my sentiments, too, and’ next time I'll keep to my side of the road if I take off the panel of a fence.”” 1 did want to speak of the right of a girl to do & man’s work and do it well for less than enough to buy her clothes and food, but that will make another stozy. Ouve Hevoex, John Chinaman on the Cliflv\)ellefs A group of Eastern tourists dropped in yesterday at the museum of the California Academy of Sciences and were soon deeply engrossed in contemplation of the minia- ture reproduction of the homes of the cliff- dweliers of Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado. The scientitic method adopted to bring up these scenes of antiquity is the plaque plan, the wails, battlements, precipitous cliffs, etc., appearing thereon in relief. Thescale being largely reduced, it is possible that the overhanging cliffs which menace the roofs and heads of the sup- posable ancients are a littie too beetling and the cliffs are a trifle too lofiy and pre- cipitous and inaccessible. “Ab.” sighed a very emgaging young lady, “how could any one ever live up there now?"” “‘Suppoce g0 see hole; that for ketchum inside,” said a Mongolian bystander. “Window, you mean,” interrupted the fair Easterner, “Do 1 understand you fthat these interesting people climbed in at the windows?" “All samee climb in at window. Man he walkum heap hard until he climp up, four, five thousand feet.” **Yes, and then #** “He lookum down, see heap high; he falluom down into soup—what you call him ?” “Soup? Oh, yes, I understand. The aboriginal feil into the soup. How in- teresting.” *‘8’pose he not walkum. Then man at top he huulum. He go up, up, all same like Chicago house—heap way up.” “Did you ever see the cliff dwellings?"’ This question was asked with fine Bos- teonian irony. “No," admitted” the Chinaman who knows “No, but I lived three all. Chicago and I savey Chicago choice in its way and peculiar and inter- esting—the above-mentioned loan collec- tion at Campden House, a collection of the drawings and studies of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and a collection of drawings “illustrating society,’”’ us the catalogue modestly informs us, by Mr. Charles Dana Gibson. Campden House is one of the big old- fashioned mansions of Kensington; the great garden surrounding it, the shaded walk leading to it, make it rather impos- ing; but it is not better adapted for hang- ing pictures than the Hopkins house itself. Itisnot only necessary to be able to see pictures by walking around them; it isa pleasure to be able to see them at their best. That.is possibie only in a well-ordered gallery or in a studio. Over the inner doorway of the entrance hall the little *‘Strawberry Girl,”’ by Bir Joshua Reynolds, had been executed. It was possible to see the big eyes under the unchildish turban, the little hands crossed one over the other and the general dark richness of the color—but the actual color itself was as invisible as the strawberries, for which latter iact the absence of light and the hanging were not responsible. Two portraits—one of Mrs. Hickey, one of Charles James Fox—were not very in- teresting. The Romney portrait of Mrs. Glyn made me long for the old fashions of powdered bair and folded kerchiefs, and the clear, almost'childilke expression of the faces of the women of that period. Romney's portraits have retained a won- -derful purity of color—the liquid blue of the eyes, the touch ot crimson on the lips have almost the freshness of wet paint— and who better than Romney could paint a head at once spirited and delicate? - The grayish hair that is blonde under the,powder, the transparent white of the kerchief—the melting color of flesh in light, against light, with light all around it—"‘receive the assurance of our most aistinguished respect,” George Romney. “‘The Mushroom Picker’” and a small “Full Length Figure of a Girl” represent Gainsborough—not too well. *“The Muash- room Picker” is interesting technically because it is unfinished—it is bardly more every pioture in the place as shadowy as | | head seems to be turned aimost to the Three Small Picture Showss in Liondon Town than pegun—washed in, in a rich dark brown and ascumble of lighter amber. Hogarth is responsible for the white- headed, red-coated old feprobate hung in the refreshment-room; his small, blue twinkling eyes look down upon hills of micrascopic cakes and transparent sand- wiches—his face is almost apoplectic in color, Time has been kind to the harsh, firm color—to the thickly painted red face—but it must have been rather un- pleasantly vivid when the gold frame was new. And opposite over the teatable scowls Prince Rupert by Albert Cuyp. Prince Rupert is a formidable gentleman in a red velvet cap and flaunting feathers—there is a storm brewing in the landscape behind him, and his dark hard face, rather bilious in color, with bold eyes and a thin line of cruel mouth under an equally straight and thin line of mustache—is hardly less awe inspiring. The refreshment-room has been.more than honored. In the corner we meet the cold glance of George ' Villiers, second | Duke of Buckingham. Reserved, distin- guished, with a long, tine-featured face, painted in cool gray flesh tones, a great point lace collar cooter and grayer still, this portrait has almost the aristocratic distinction of a Van Dyck. Itis by Cor- nelius Van. C. Jansen, who must have been | the contemporary of the great master—but C. Van. C. Jansen had more sense of color than of form. The head is rather badty out of drawing. A portrait of Charles Edward by Allen Ramsey shows & young man with a smil- | ing countenance against a sunset sky; his back of his neck and his shoulders are shrugged only on one side. Lord Byron and Campbell, mellow with age, are hung as companion pictures; the | familiar portrait of Lord Byron, pale, noble, with his beautiful melancholy eyes BY JAMES McNEIL WHISTLER. her side trolling hgd on her loved shojders, all the homelydetails of a respectalle rather meager lusehold are indicagd with that knowedge of a man whd under- stands his medium and uses it to the test ¢f Hs ca- pacity. And lere at the end of tie room the little girl stands, very erect nd_ yery self- possessed, in a rather stately, if entirely childlike, dignity. And the swulof every painter beats almost audibly a: he rezards it. If it be not treason I woud suggest that Miss Cicely Alexander coud te hung next to the Infanta Margheris, in the Louvre, and the masterpiece of San Diego di Velasquez would not seem more re- markable. § Some one has recemtly wriiten that Whistler’s art is the quintesseme of all that the ninetéenth century has b offer to the artistic gourmet. He bas taket to him- self the best of every art with waich his subtie and delicate fancy has leen mo- mentanly impressed. In his yotth the mysterious charm of the creations of Dante Gabriel Rossetti surrounded him; something of their still, deep glance is in the eyes of all of Whistier's women and children. Impressionism as it was first unde_rswqd taught him the lesson of sarrounding his figures with air, of bringing them forward out of cool depths of background by atten« tion to the form and modeling of the points where lights and shadows meet. From Velasquez himself he gained his beautiful great lines, the simple solid backgrounds, the lovely silver-gray tone, and from she Japanese, at last, he took the understand- ing of great flac masses of colar, the dec- orative arrangement and the wonderful attention to detail, which makes every jar, every flower he adds to his composi- tion absolutely necessary to its perfect harmony. Whistler's powerful tongue is a weapon to be feared and his whole scorn is di- dicted against the realists, whose creed is contained in the single rule that nature cannot err, that everything in nature is fit subject for the art of the painter, that to make a servile copy of the model, not closing an eye to one unpleasant or inhar- monious touch, is the beginsing and the end of the first and the last lesson. To Whistler nature 13 a vast garden, from which he plucks only the flowers that he desires; his world is a world of music in which every dis- cord, by subtle rela- tions, by careful se- lections, can. be used in a general har- mony. In hisown lit- tle pamphlet, which, alas! I am not able to quote word for word, he says some- thing like this: “When the veil of evening falls mildly over the banks of the rivers; when the little houses sink into soft mist; when the tall chimneys look like church towers and the ware- houses gloom like palaces in the night —when the” whole world joics and is one with the vast sky, and the twilight wonderland is before the enchanted eyes— then the Philistine ceases to understand, because he has ceased to see sharply everything, every de- tail — the bald, the ugly, the shapeless truth.” The portrait of lit- tle Miss Alexander, done long ago, was one of his first and most striking suc- cesses. After his first picture had been re- fused at the Salon (that wonderful following the interested visitor even to the | remotest corner of the room. The modern men are here as well. Lord Leigbton's Flaming June, Electra mourn- ing at the tomb of Agamemnon. The music of the sea, the dignifiea, careful work of the late president of the Royal Academy. His successor has sent, in piace of the “Flaming June,” which was only exhibited for two days, a portrait of achild called *The Deserted Cage.” Sir John Miliais is ill and suffering. Heis almost as popular as the late Sir Freder- ick, but when he sends a canvas like “The Deserted Cage” he almost forfeits sympa- thy. The cage is hardly as vacant as the child’s face, and is certainly drawn with more interest. The cheap vopularity of the subject is the touch too much. Let us turn to the “Gambler's Wife,” which is an old canvas, but which has lost nothing of its careful, if rather sweet, coloring and composition. The Jandscape by 8ir John Millais is called “The Old Garden,” a very clean old garden, with a weather-stained cupid blowing a horn on the back of an ani- mated dolphin with the fine silver jet of a fountain tossed up from his great jaws. The garden has smooth walks and clipped trees and hedges, and is just such an old, sheltered, sunny place as we may wander into any day, if we are fortunate, even in smoky London. ‘Watts is represented by several portraits. There are two beautiful dark Jandscapes by the late Henry Moore. Alfred Parsons has his rather conventional blooming fruit trees against a windy sky;.there is a Frank Hall,' and two jolly Sir David Wilkies, “A Peddler Showing His Wares,” and ‘“'The Penny Wedding,” from the Queen's collection. There is a David Teniers, even a Marillo. Butitis impossi- ble to stay away from the portraits at the end of the middle room, with the light streaniing in between them, and the glass which protects them giving maddening reflections of all the other pictures one does not care {o see, and of all the people in bright dresses, who might be more profitably employed 1n the daily passing show in Hyde Park. 1t is hardly in an amiable spirit that we pause before the Whistlers; it is 1n uncon- wroliable bad temper that we regard the great canvas of Luke Fildes, the anxious doctor looking into. the white face of the sick child, upon whom the rather theatri- cal lamplight is tiirned. In justice to the| big emotional picture that occupies the place of honor, it is well conceived, well drawn and well painted, soberly and hon- estly,. The mother who has her head ‘buried in her arms, the father standing at | woman in white which made the Sa- lon des Refuses of 1863 a’ conspicunous and distinguished exhibition) Whistler settled in London and very soon after the present portrait was painted. Miss Cicely Alexander makes ns think of the little Spanish princesses. It is per- haps the dress, which is of white muslin, with wide sleeves and a skirt that bangs out in crisp stiffness like the skirts of a ballet dancer. The child hasa large gray hat in her hand, with a black ribbon and a floating feather. With white and black and gray, and a tone hardly warmer over the siiver-blonde hair and the soft little lumi- nous face, with the big eyes and the one touch of crimson on the lips, everything that could be said has been said. Did Whistler give or had the child really all that soft dignity, that mixture of reserve and graciousness, that fine flower of an appealing, shy reserve that is as intangible as a fragrance? The delicacy of extreme youth rests upon the little figure as lightly as -the two butterflies of pale gold that have fluttered into the background, or the gold-hearted daisies that tremble in the shadow behind her. On the opposite wall, equally badly hune, hangs the older sister, not quite so delight- ful and equally indescribable. A young girl in black, thatis not dead, that 1s not shadow, that is a clear, fresh, soft light-black; the head veinted low in tone; around the necka bitof transparent white crushed muslin, 8h¢ 1s buttoning her gloves and looking outof the canvas, In the background, the which isof yellow- ish-gray, there is & dark fir, and a flutter of tiny vivid yellow flowers. In both por- traits even the signature ems indispensa- ble, that characteristic buiterfly caught on the wheel. The nocturne is one of the dim-blue evenings, Whistler so Isved to paint, and which started the rage fir peinting moon- lights and starlights and twilights as no- body ever before saw them. Itisalmosta heartbreak to think tiat these portraits are not in a public gdlery, although the geuerous frequency with which they are exehdiblbed cannot be 0o highly appreci- ated. At the Fine Arts we see the drawings and studies of Sir Hiward Burne-Jones, It would be well to Mrn the entire art school into this little exhibition, in order to marvel at the undring energy, the re- m:rnble industry d this wonderful man, who, although over 60 age, makes "hiss{adies with the sam pels: taking care, the same devotion to every detail that characterized the youth of ail the great descendartts (if they may be so called) of the gwatest of all the pre- Raphaelites, Dant Gabriel Rosserti, | Vax Dyck Brows.