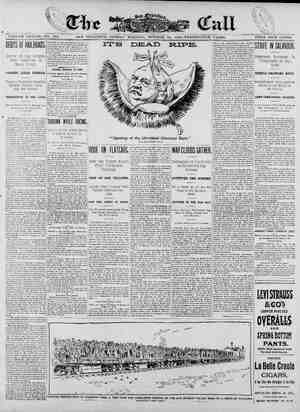

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 20, 1895, Page 13

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

i 1,0 LA B irage, from mirer, to look at carefully. An optical illusion g from an un- equal refraction in the lower strata of the atmosphere and causing remote objects to be seen double as if reflected in a mirror or to appear as if suspe It is frequently scen i serts, presenting the appearance of w Noah Webster. So much for Webster and the rest. They get it al books—out of books that get it other books. Why not, like Edison : good oid Mother Nature? Have seas, rivers, forests, herds, all thines that are or have been—have things, , as well as man, souls that sur- here is & sort of poets' corner in Oak- nd—that is, if a wide, shaded and wealthy street in the heart of a populous city can be called a corner. But it is truly a ‘‘corner,” so far as the world goes, or comes. way. The iron track of trade makes a diversion, as if for the sole purpose of keeping out of this quiet corner. And so the cats and the birds and the othe: singers have it all their own way. ve place it i t the dead have got up d gone, gone for good, they say, all ex- cept one wealthy old man, who comes back now and then to hunt up the silver dles of his rosewood coffin. see, when they took him up, in or- his grave into a corner lot, find only the silver door-plate and this plate and his shin thi iest of all the rich ind to take with ghostly arms to his nice new Il never find the silver handles by looking down there in the pretty rose bushes and un- jer the sweet green grass of the new lawn. He n look up in the treetops for them; t n of imitation silver fell to pieces right soon, along with the imitation | wood coffin, and a locust tree sent its indust roots down there at once and tock the corroding iron away up into its high top to make into white blossoms and perfume and honey for tke bees. Ah, how busy is nature and how know- ing! The only coffin, in fact, that was found at all in shape was that of a poor borer, and it was merely a big, oblong ood box. Come here, then, ye of far is, who hope to pull ves to- gether hastily when the last trump sounds, > poor and sleep in a California red- till the everlasting morning. get out of this graveyard, ; another graveyard in now the best and the health- oets’ corner.” ¥ woman presides here; o might be great some day if forget that she is commis- n to vote and hold o forget to continually f a firecra . Then there is the stately Madonna ; then there is the pretty petite, mpting as twin apricots. A iroad man hovers about here, and ally has a heart, although he, like v another man in this iron age of rail- s, would rather be accused of almost ther crime or misdemeanor than Then some of the university men zet the shades of Berkeley and Stanford i poe about this “poets’ corner’ a )d bit. A few of the newspaper people of the two cities are also seen to goup and down here oftentimes when off duty, and there isa man who has been accused of being a poet (a very serious accusation in | this day and age, for it makes him liable | to all sorts of other accusations), but he never denies anything, not even this. Well, these comers and goers of the “poets’ corner” were gathered together here to listen to a poem—a sonnet. 1t was called “The Mirage.” Now, there was no doubt about the question of the poem. It is a poem; but what is a mirage? Every one asked the question—every one tried to answer it—and every one an- swered it differently and indifferently. The railroad man knew all about it. Yes, he had seen thousands; had seen cities, ships, cars; had seen commerce afloat in the air in every form dauring his thirty years west of the Rockies. A painter present had seen pictures of indescribable glory on the arid and ashy Mojave Desert; a one-armed general had seen banners and bayonets glittering above an army of mil- lions. Some of the ladies (God bless them), finer than the men, had seen gay and thronged summer resorts so inviting and magnificent that they were surely »osts of paradise. Then, one after another, upspake the learned and solid old professors of the two universities, born doubters of all things, as all such men of books are, and stoutly in- sisted that a mirage is merely what the be- holder imagines, dreams about or desires, and they instanced, as in evidence, the fact that the talltoad man eaw only com- merce and its varied adjuncts and at- tributes, the soldier saw armies and the ladies summer resorts and superb gowns. And one of these grave men went so far as to say that this very grave subject was born of the fact that we were gathered to- gether in a gravevard atmosphere, fanned into a little breeze a little time before by the foolish story of the rich dead man hav- ing been seen hunting for the handles of his coffin one moonlight night by the mul- titudinous and terrified cats. But away with levity! I say, my wise men whose eyes are covered with glasses then wa in by the lids and leaves of books, that I have seen things these forty years past that I never could have imagined, and, goodness knows, never de- red. And this is all I shall now say of 1 things on my own account. But I &m going to let down the outlines of what my old partner, Mountain Jo, one of Fre- mont's men and the first proprietor of whatis now Castle Crag Tavern, told me forty years ago of his experience with a mirage when crossing the southern plains With the Pathfinder in 1848, Substantially the story is history. Of course Fremont vever brought the mirage into the account Commerce turns back from this | A dead- | est part of the proud | a, and let us con- ker string of small smart- | NIA i ik | of his terrible disaster. I donot even know | that he believed in anything of the sort, | but we all know that public men have to | be careful in this day of sharp pencils lest | they invoke derision. | In 1848 Fremont organized his fourth great expedition, this time entirely at his | own expense, and set out to find a south- ern route from the Atlantic side of the | continent to the Pacific Ocean. His equip- | ment consisted of 33 men, 120 mules, and | all the ordinary munitions of war or of peace that might be required in subduing either the savage or the soil. He secured good men, but, relying too entirely on his knowledge of the vast and trackless re- | gions washed by the waters of the Upper | Rio Grande, the gallant explorer lost his way, and nearly one-half his men, to- gether with all the animals and munitions, ‘When men reflected that Fremont had already thrice crossed the formidabie | Sierras in midwinter, had literally lived for years on the burning sands of the des- erts and yet had not lost a single man ex- ept in battle, this fearful loss of life and property seemed inexplicable. | _ But after atime some of the survivors. | Mountain Jo at their head, who had made | their way back 1o Santa Fe, where they re- | organized and from which point they | finally reached California in 1849, began to | tell, in a strange and mysterious manner, of a great river and a wonderful city which they had seen in the heart of the desert. There were those among them who be- lieved that this city was one of the cities of gold for which the Spanish cavaliers had searched and searched so long and | vainly centuries before. Surely they be- | lieved they saw spire and dome, mosque and Iinaret, tower and battlement, all tumbled together in opulent and most glorious confusion; but of course most | men shook their heads and believed the | men had been half crazed by their suffer- ings, and did not quite know what they | had seen. | The great explorer had chosen Mountain {Jo as his second in command. This expedition was made up mainly by Southerners, men fresh from the war | with Mexico. Fremont was a Southerner | and the flower of the South was his fol- lowing. His famous father-in-law was still standing up in the Senate, pointing to | California with his prophetic finger and | erying out to the dull and doubting world | the words that now emblazon his statue: | “Yonder in the West ligs the East! Yon- | der lies the path to India!” | Fremont's lieuterant in this expedition ha¢ held a command in the Nauvoo or Mormon Legion. This ,Mormon Legion had been disbanded in Mexico in order, say the Mormons, to keep them out of the | country and bresk up their church. But it is on record that they asked to be so dis- banded. Salt Lake was then in Me and not so far away, they thought. of these Mormons of tnhe Nauvoo Legion while making their way to Salt Lake had stopped at Fort Sutter, found work with Sutter, and while employed under John Marshall, his foreman, on the millrace had found the first gold known to white men in Alta California. These men had communicated with Mountain Jo, hence his position, his confidence. Santa Fe was reached soon, safely; but not passed so. There was delay an delay. Seme would linger, would live here al- w. in this poppy land of eternal after- noon and of pleasant loves. Some would wirn back. Terrible was the way before them, said some. Too many had gone al- ready, said others, enough to carry away | all California. But at last the expedition led straight for the seas of fire and the setting sun. Two black and bitter hearted Mexicans agreed to set out as guides through the great unknown, but they would not con- sent to go further than the top of a great mountain range which they said was the end of all perils, and from which they said they could point out a river and a valley of surpassing beauty and verdure in the world below them. The hatful of silver which they were to receive would be enough to open a monte zame in Santa Fe, they said, and they wantea no more, and so would not go on to California. The Santa Fe of old was not the Santa Fe of to-day. It was astaid, rich, religious, respectable capital, with no rival, save the City of Mexico, west of the Mississippi. It had been standing there for centuries. The Governor's palace was, and long had | been, the finest public building on the | continent. It is even torday imposing, and is the oldest public edifice in use on | American soil. This city is ages older | than Quebec, Boston, New York or New Orleans. It is third in date of foundation | on the continent, San Antonio being sec- ond, Saint Aggustinefirst. Yetso little was known of Santa Fe at the time when she was ceded to us that the Government at Washington sent an expedition to see on what river the city stood and if navigation could be opened to her gates. And yet the ink was scarcely dry on the treaty when Fremont’s great expedition set forward to ‘pie!‘ce the burning wastes. Marvel not, then, tbat men ran here and men ran there, still half believing the old Spanish stories about cities of gold, of castles on mountain tops and of enchanted valleys below. Pleasant enough was the journey for | some weeks after leaving the ancient city | of the Holy Faith; then grassana water | began to fail on every hand. At last there was no grass, then no water. The brown, rock-built mountain was bare as lava, save here and there a | dwarfed juniper tree, here and there a brown tuft of grass in the cracks of the hot and glaring lava beds. Some horses died, some men were ready to die, but | Eremont still kept at the head, on foot, | leading his horse. That last day, as the huge red sun fell down wearily before them, the top was jreached and the two guides came up. They threw out their hands, they cried, “Que hermosa!” (how beautiful!) Then they held out their greasy, big hats for the silver. It was quite a load, but Fremont ‘poured the money into the two hats ‘WHEN THE STREAM, IN A DREAM, WANDERS DOWN TO THE STRAND; WHERE THE WAVES, AS THEY S OCEAN CAVES; AND THE BILLOW, BEATING HIGH ON THE ROCKY PROMONTORY, CALLS ALOUD WEEP TO THE SAND, ‘WHISPER SECRETS OF THE DEEP HEN THE INDIAN SUMMER TIME OF THE YEAR, WITH ITS SENSE OF PEACE DIVINE, DRAWETH NEAR, WHAT A JOY IT IS TO BE BY THE BAY FAR AWAY, WHERE THE WATERS OF THE LAND MEET THE WATERS OF THE SEA, TO THE BILLOW OF THE SKY ON THE OCEAN OF THE AIR TO THE CLOUD; ‘WHILE AFAR IN FADED GLORY WITH ITS ON THE HILL, OLD FORGOTTEN BELL AND ITS HALF REMEMBERED STORY, STANDS CALM AN HE MISSION OF CARMEL, D STILL. 3 and the men turned back, bowing to the | earth with thanks and silver. Yonder, away down yonder, swept the great, bright river between the greenest of | green walls. “I can see the cattle coming | down to drink,” cried a pale young man | who was dying of thirst, and he threw up | his arms and then clung to his horse’s | neck and whispered of sweetheart and of | home. A thousand, things were seen,a thou- sand things were said, ten thousand things were thought. The scene far away down there—describe it? A bolder hand than mine must try to paint its splendors, and | it must be a much better hand or fail. | There was a city, a great city beyond the | river. The men wanted water, not a city, | say the men of science, and so saw the | water first. Maybe so. Immediately they began descending. In fact they went right along and on and down faster than they had gone for days. Even as Fremont thanked and paid his | guides, they were fast passing out of | sight. Fremont was a learned man. He had begun life as a teacher, but his three expe- ditions had taught him much not to be found in books. No doubt he had heard from mountain men around the campfire many a tale of terrible delusions that had | led men to death so many times on those vast plains, tales of the alluring mirage, and now it suddenly dawned on his weary mind that this was none other than the ge and that the Mexicans had tvurned back only when certain of his destruction. He threw all his strength and energy into action and - sprang forward. He and Mountain Jo shouted to the hurrying men, made signs, did all fhat dazed and hali-dying men could do, but the few who | could now hear only paused a moment, shook their heads, then hastened on and | down. *We will bring you water at once. will make boats there of the beautiful trees and drift down to the Gulf of California,” | shouted the last man, and he almost | laughed at the pleasant idea of the boats | they should build and Jaunch on the broad, swiit river that flashed below. | Yes, Fremont knew this had been in their minds—in hisown mind—for had not the Spaniards recorded that they had sailed | down a river so deep in its bed that they saw the stars by day. Once, twice, thrice Fremont and Moun- | tain Jo rested, rose up again and followed the men; then sat down in despair, for | they, too, were dying of thirst. It was We | | the way. | We have a right to demand it, for the | George E. Pickett, one of whom is Colonel night soon and they could no longer see | They built fires of the dead juniper trees half-way down the steep to warn the men back; and they waited | there for the dawn, building beacon-fires | for the lost men. Morning at last, lurid | and sultry. A long black line of ‘dead horses, mules | and men in the soft gray sea of sand, a wavering, feeble line of living, far, far away, and that was all. The river -had disappeared, the city had melted into space. My man of science, tell me whence are these flashing waters that wash the willow banks in the burning sands and ever and ever flow on unattained! Have rivers souls? Are these the ghosts of perished | waters? Tell me, 0 man of knowledge, | whence these towers and battlements that are likened unto storied Nineveh in their | magnificence! Are not these the ghostsof | cities that have gone down in these sand- | sown deserts under the weight of a thou- | sand centuries? Isitnot true that every- thing that has ever cast a shadow has left its floating photograph hanging some- where in the air? Come, great man of science, face the mystery of the mirage. Give something more than a dull and indefizite name. Here is work for you. Are these the shadows of cities still existing somewhere? Are they resting places for our dead on their upward way? | O man of science, come out of the| murky towns of trade, where the air is dark with smoke! Lift up your face from the books of dead and buried days and come where the air is pure and clear, and see, perhaps, the face of God as it was seen in the burning bush by the blazing banks of the Red Sea. Say, please say, what is this mirage? We, of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizoua, demand of our great universities something more certain than the Jdictionary sop. mirage in its California perfection has been discovered since Webster's Dictionary was built. THE PICKETT CHARGE. Members of the General’s Staff Give Details. The Baltimore Sun says: The surviving members of the staff of Major-General W. Stuart Symington of Baltimore, have issued tne following statement, which ex- plains itself: ¥ We, the undersigned. having seen an article from Colonel K. Otey in the Balti~ more Times to the effect that he has heard many queries, conjectures, etc., as to Gen- eral Pickett’s position and connection with the movements of his division in the third day’s battle at Gettysburg, and has never heara any satisfactory answer to them, desire to make the following statement of facts in regard to the matter: ‘When the division arrived on the battle- field on that morning it took a position slightly in the rear of the artillery com- manded by Colonel 1. P. Alexander, and General Pickett was directea to hold him- self in readiness to move against the enemy’s position whenever notified by Colonel Alexander that the Federal artil- lery was sufficiently disabled to render an assault practicable. One of General Pickett's couriers (Mar- tin Campbell by name) was left with Col- onel Alexander to bring his notice to Gen- eral Pickett whenever he thought the proper time to move had arrived. The artillery duel, as is generaily known, raged for about two hours, and at the end of that time there was an evident slacking of the enemy’s fire. Colonel Alexander then sent to General Pickett the notice to move, under the im- pression that the Federal batteries were to some extent silenced. This proved afterward to be a mistake as alull in their fire wascaused by a tem- porary want of ammunition. When he re- ceived the order General Pickett placed himself at the front of his division and gave the order to advance—Kemper and Garnett in front, and Armistead iu the rear. as a secona lineof attack. A short time after the movement began General Pickett assumed his proper vosi- tion in the rear ana center of his line of battle, moving forwora with his division, actively directing its movements, and in everv respect participating in its dangers. In no other position would it have been possible for him to know what was oc- curring all along the line or to discharge the duties which every pracucal soldier knows would devolve upon a major-gen- eral commanding an important movement. When the attack failed he personally superintended the withdrawal of his troops and the formation of the remnant of his division along a new line near our original position, That there could possibly have been any doubt as to the facts above mentioned is a matter that will never be comprehended by any man or officer familiar with the facts. MY MAN OF SCIENCE, TELL ME WHENCE ARE THESE FLASHING WATERS. WHEN BOOTH WAS NOT BOOTH. A Martling Reminiseence BYeS SAM DAVIS. There is a small and cheap restaurant on Merchant street where I make a point to 80 once a day, at least, when in San Fran- cisco. In the old days when Clay street was the newspaper center of the town I spent many a pleasant hour there, mingling with comrades who have passed away. The same waiter is there now who served frugai Bohemian meals twenty years ago, and the same proprietor is be- hind the counter. For many years nota single familiar face of the past has greeted me except when I invite some of the old boys to come and dine. It may be the cooking or the loneliness of the spot or the surroundings that affect my guests, I know mot which of the three causes, but I have noticed that I find it hard to get even my closest friends there twice. They generally insist upon it that I shall dine with them, in order, I imagine, to escape dining with me at that old restaurant. They always accept my invitation until we edge down toward that particular establishment and then cook up some flimsy excuse to dine elsewhere. These people are evidently persons who regard restaurants merely as places in which to eat. With me it is different. The food and service may deteriorate in quality, as in this case, and the proprietor grow old and crabbed, but if the spot has associations and memories dear to me, the cuisine, 1f such an expression is permis- le in connection with so plain a place, can go to the devil, and I am still content. The pleasant hours I have spent there all come up again, and every bubble on the surface of the cheap wine has a face and memory init. ButIam spending too much time. I wish to tell a story that I don't expect any one to believe aiter I have told it. I used frequently to meet there a man named Johnson, who was introduced to me by Harry Larkyn. Poor Harry, who lived long enough to excuse himself to some ladies after a bullet went through his heart, to step out of doors to die. This always struck me as more pollte and thoughtful than was Chesterfield, who, with his last breath asked an atten- dant to give a visitor a chair. Larkyn, after his death wound in Calis- toga, bowed politely to three ladies, asked to be excused, and stepping from the room was a corpse. How I miss Harry’s face when I dine at that little Merchant-street restaurant. One night Larkyn, Johnson and myself were there. Johnson was an actor, one of those talented geniuses who for some reason or another never seem to succeed. The queer thing about him was that he re- sembled Booth both in face and figure, and could mimic him to the life. We would often take a little room by ourselves and after dinner Johnson would give us scenes from Shakespeare, and for the time he seemed Booth himself. Larkyn was ‘'very solid,” as they say, with the theat- rical people, and he made many vain at- tempts to secure an opening for Johnson, but the managers all said that Johnson wanted to fly his kite too high at the start, instead of taking subordinate parts, etc. Larkyn was considerably incensed at the treatment his friend received and the man- agers were in constant fear that his sharp pen would manifest his displeasure in his theatrical criticisms, for he was gn all- around contributor to the papers and very happy at theatrical work. But he was too broad a man and good-natured and forgiv- ing to take such a petty revenge. One evening when we three were dining together, Larkyn unfolded a plan by which Johnson was to play Hamlet at the Cali- fornia. “Be all ready,” he said to his friend, “to play Hamlet next October at the Cali- fornia. I'll fix it.” “Why Booth plays there in October. You talk nonsense,” was the reply. “But I’ll have Booth give you a night.” “Pshaw!” “But, by jove, old boy, I'll make him give you a mght.” Johnson merely removed the wine bottle from Harry’s reach and grinned. “Now listen, both of you,” said Harry. “I know Booth well. Met him years ago in New York. He will play Hamlet three nights the second week he is here. I got the whole programme from Barton Hill. The last is on a Saturday evening, and on that particular night, October 16, you be ready to play. You are, as you know, the dead image of Booth. I will have Booth out to dinein the afternoon, and if I ever get my hands on him he will never show up at the theater that night. You occupy his dressing-room and go ahead. You attend to the stage work, Sam will help you in the dressing-room and I'll at- tend to the outside business.” The audacity of the idea staggered us not a little at first, but Larkyn had a per- suasive tongue and soon convinced us that the only thing that really detracted from the plan was its utter simplicity, and we soon began to work on the details with feverish enthusiasm; but after Booth arrived and the town went wild over his work I began to wonder if my friend John- son would be equal to vhe task we had im- posed upon him. It seemed an awful thing, this practical joke we were about to perpetrate, and I began to wish myself well out of it. 1 suggested to Larkyn the propriety of call- ing the whole business off, but he brushed aside my misgivings, insisted that I had concocted most of the job and invariably wound up by charging me with treachery to Johnson—who. he said, would surely commit suicide if cheated out of his chance to play Hamlet—or a lack of nerve. A man, especially a young man, hates to be taxed with treachery or a lack of nerve, and [ finally assured Larkyn that if it be- came necessary to cut Booth’s throat to keep him off the stage I would allow him to do it, and never mention the matter to either Crowley or Lees. The time drew near for the event, John- son was working like a beaver at study and rebearsal, and every day was taking a fencing lesson of a good instructor. What astonished me most was Johnson’s nerve and determination. He had no thought of l failure. All he wanted was Booth's cos tumes, the stage and an audience. One afternoon I got a note from Larkyn to meet him.at the Merchant-street res taurant. I went up, and there he had | Booth caged in the little dining-room where we always dined. I felt a great strain on my nerves when I was intro- duced to Booth. I thought Larkyn should have had a little more regard for me than to have brushed me up against our in- tended victim. Nothing on earth ever phased Larkyn, but with me it was quite differens. I felt ill at ease, and when Booth turned his big eyes on me I wondered if he was reading the secret. ‘“‘Harry,” said Booth suddenly, “what’s this talk in the papers about my intention to give the public a new version of Hamlet? I saw it only vesterday in the Post.”’ “I wrote it,”” replied Larkyn, as he filled his glass. ““You know there has been a lot of talk that you had played Hamlet so often that you had fallen'into a rut and could only play the one version. Of course, I know better, and I casually mentioned the fact that during your stay here you would demonstrate the folly of the one-rut 1dea by giving the public a new version, Of course it would be no trouble for you to do that. Itwould demonstrate your versas tility and be a great treat.”’ Booth’s face wore a clouded look and then he laughed. “I suppose vou would have the manage« | ment advertise a complete change of | Hamlet every night, and the actor wha could present Hamlet in the most char- acters would knock the persimmons, eh?” After considerable good-natured chaft between the two.we_ finished the dinner, | which Booth seemed to relish. and in a | joking way said that he should give the ublic a different version of Hamlet on Saturday night and have a line on the bills | to that effect. Booth joked of the matter about the hotel until it began to be talked of through the city, and like most theatrical rumors spread with amazing rapidity, which played exactly into Larkyn’s hand and put | him in the highest spirits. I even had to agree to sleep alone so that in my troubled dreams the plot might not escape. Well the night- at last arrived. Booth was wearing off the drugged effects of Harry’s dinner in a deep slumber at the | hotel, his valet was properly drunk in a Clay-street saloon and all was well. We got the key to the Hamlet ward out of the valet’s pocket, and at 7:45 Johnson was arrayed as the melancholy Dane at the California Theater. The place was packed and the sign “standing room | onl was up. At 8 o’clock I put the finishing touches on Johnson’s wig and bade him brace up. He was pale and nervous as almost any one would be under the circumstances. He had two parts to play, Hamlet and Booth. I gave him a few words of encouragement and a small nip of brandy and turned him loose. He strode cn the stage, faced the foots lights, and_then what a roar of welcome went up. He bowed with studied dignit; and the noise subsiding he began to speal his lines. In a few seconds he had recovered hig composure, and it seemed that it was ine deed Booth who stood before the audience. Presently the old playgoers who watched every move began to whisper among thems selves and exchange comments. Yes, indeed, he was giving the public a new version. George Bromley liked it; Colonel Cremoney didn’t like so well; Scott Sutten declined to express an opin- ion; Joe Goodman was very reserved, and George Barnes fell to wrangling with Peter Robertson about the inflection he gave certain lines; Colonel John McComb of the dear old Alta was just a trifle restless, Presently the place became noisy with dis cussion, and in the midst of it Hamlet stopped short and turned a full, reproach ful look upon the pit. A silence fell over that portion of the house. and the critics fell several inches in their seats. The withering, silent reproof that blazed from Johnson’s eyes seemed like a command from Olympus. The gale lery broke into applause at the discome posure of its natural enemies, and the rest of the house took it up. “Great work. Oh, wasn’t that a daisy play of his?”” I turned, and it was Larkyn talking over my shoulder. ‘When the curtain_dropped on the firs act_there was a look of complete triumph in Johnson’s eyes. He felt that he had won the attention of the great audience, and the applause was water to his parch dramatic soul, that had never quenched its thirst with such a delicicus draught before. Near the end of the fourth act I was are ranging things in the dressing-room when I was counscious of a presence. Looking up I saw something that caused me to stagger. There stood Booth, the real Booth, in plain clothes. He simply fixed a look of astonishment on me and we both stared at each other; then in walked Larkyn, who for once in his life seemed at a loss for words. Presently Johnson came off the stage and oined the group. Such a quartet of speech less and astonished veople I never saw 1 my life. Each man seemed to think that it was somebody. else’s turn to speak. Finally Booth, with a slight bow to Johnson, said: “You seem weary with your exertions. If you will hand me your costume I will play the last act.”” Johnson somewhat nervously took off “the trappings and the suits of woe” and Booth began to put them on. We all me« chanically assisted him. After he was are rayed in the garb of Hamlet we deemed it prudent to withdraw from the dressinge room, and melted away as it were without the formality of excusing ourselves. Booth never seemed to notice our disappearance. He plaved the last act as he never played it before, and the house.was ina roar of np%rova s While he was bowing to the repeated calls of the audience noor Johnson sat there half clad and the picture of discons solation. He was about to slink home when Booth extended his hand and with a pleasant smile said he had noticed a pors tion of his acting and was highly pleased with it. Then he shook hands with all of us and we had a hearty laugh and Booth gotin a good humor and we all slipped off after the play to the little obscure Merchant-street restaurant and made a night of it. 11 enjoyed it except Johnson, wha séemed utterly miserable. When we sepa« rated Booth invited him to become a2 mem= ber of his company, but he never showed up, and about two weeks later died in the ome for the Inebriate. As for the performance, the papers praised it without stint, and not one of the critics ever knew of the imposition, as we all swore secrecy and maintained it so long that I hope the dead members of the guars tet will this day forgive me for breaking the vow of silence. robe