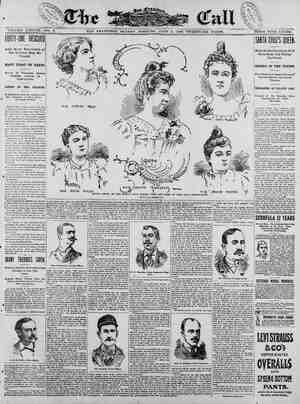

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 2, 1895, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

> 4 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDA 23 Slumber Song. In the winged cradle of sleep I lay My darling gently dow Kissed and closed are the eyes of gray Under his curls’ bright crown. ‘Where, oh where, will he fiy and float In the winged cradle of sleep? Whom will he meet in the worlds remote, Where he slumbers, soft and deep? ‘Warm and sweet as a white blush-rose, His small har But Y cannot Andhe through nigh 1o troub! when the dawn shall break, tchless baby charms, his love and Into my happy a CELIA THAXTER. Little Pitchers. ‘A chiel's among you takin’ notes,” quoth Robert Burns. And what a sermon with this good little boy, nothing ever turned out with him the way it turned out with the good little boys in books. They always had a good time, and the bad boys had ‘the broken legs; but when he found Jim Blake stealing apples and went under the tree to read to him about the bad little boy who fell out of a neighbor’s apple tree | and broke his arm, Jim fell out of the tree | too, but he fell on him and broke his arm | and Jim wasn’t hurt at all. % There was nothing in the books like that. And when some bad boys pushed a blind man over in the mud and James went up to help him and receive his blessing, the blind man did not give him any blessin, at all, but whacked him over the hea with his stick and said he would like to see him shoving him over again and then pretending to help him u%. This was not in accord with any of the books. Jacob looked them all over to sce. Once when he was on his way to Sunday- school he saw some bad boys starting off in a sailboat. He was filled” with conster- nation because he knew from his reading that boys who went sailing on Sunday invariably were drowned. So he ran out on a raft to warn them, but a log turned and slid him into the river. A man got | him out pretty soon and a doctor pumped the water out of him and gave him a fresh start, but he caught cold and was sick in bed nine weeks. But the most unaccount- able thing about it was that the bad boys in the boat had a good time all day and then reached home alive and well in the most surprising manner. When Jacob got well he was a little | discouraged, but he resolved to keep on trying anyway. e examined his authorities and found that it was now time for him to go to sea as a cabin-boy. He called on a ship-captain and when the captain asked for his recommendation he proudly drew out a tractand pointed to the words, “Jacob Blivins, from his affec- tionate teacher.” The captain said that wasn't any proof that he could wash dishes and he §uessed he didn’t want him. This was altogether the most extra- ordinary thing that had ever hapoened to TWO LITTLE HOME BODIES, [Drawn jrom a photograph.] phrase. 0 omnipresent are the children that if one would escape the terrible jus- tice of their simple and straightforward ons, if one would not have his imprinted upon the virgin pages of a child’s memory, it becomes necessary to be the tning one would seem, if there are en in the house. ven the babes in arms are ‘‘takin’ notes.” [ myself remember distinctly the g of distress and resentment engen- red in my small mind because my elder brother, sent to rock me to sleep in the cradle where I lay, used to shake it savagely, making me afraid‘ of being thrown out, as perhaps I had sometime en. 1 was perrectly conscious of being injured and of being without redress, and membering the ache in my infantile head and heart. I am sure that I could not talk, and so suffered from the inability to express my suffering, Again I remember distinctly a shocking phrase or statement which 2 woman whom never saw after I was four years of age uttered to my mother in my presence. 1 pondered the words and their meaning_ in my heart for a lifetime, always recognizing them to be vile and always recalling the woman’s looks when she spoke them and always my mother’s gentle ““be careful, please; remember, little pitchers have big ears.”’ Tears of repentance may wash out the record of our sins from the book of the recording angel, but no such miracle is to be wrought in the minds of the little ones who watch us with innocent and trustful eves. The record of our words and deeds is written inevitably and internally in the brains of our children and other people’s children. Thetr lives and the rivcs of those who shall come after them are influ- enced irrevocably by our chance sayings, shaped in imitation of our wise or foolish doings. The Story of the Good Little Boy Who Did Not Prosper. Once there was a good little boy by the name of Jacob Blivens. He always obeyed his parents, no matter how absurd and un- "eusonable their demands were; and he always learned his books and never was late at Sabbatb-school. He would not play hookey, even when his better judg- ment told him it was the most profitable thing he could do. He would not lie, no matter how convenient it was. He was so honest that it was simply ridiculous. He wouldn’t play marbles on Sunday; he wouldn’t give hot gennies to organ-grind- er’s monkeys; he didn’t seem to take any interest in any kind of rational amuse- ment. The other boys could only conclude that he was “afflicted,” so they took him under their protection and never allowed any harm to come to him. This good little boy believed in they boys they putin books; he had every confi- dence in them. He longed to come across one of them alive, but he never did. Whenever he read about a panicu]arlg good one he turned over quickly to the en: to see what became of him, because he wanted to travel thousands of miles to see what became of him; but it wasn’t any use. That good little boy always died in the last chapter, and there was a picture of the funeral, with all his relat ions stand- ing around in pantaloons that were too short and bonnets that were too la_.rga, and everybody crying into handkerchiefs that had as much as a yard and a half of stuff in them. g Jacob had a noble ambition to be put in a book, with pictures representing him gloriously declining to lie to his mother, und she weeping for joy about it, and pic- tures representing him standing on a door- step giving a pem:( to a poor beggar woman mfi: six children, and ‘telling her to spend it freely, but not to be extrava- gant, because extravagance is a sin; and ictures of him magnanimously refusing E) tell on the bad boy who always lay in wait for him around the corner as he came from school and welted him over the head witha Jath, and then chased him home, saying “Hi! hil” as he proceeded. But somehow nothing ever went right Jacob in all his life. ‘He could hardly be- lieve his senses. This boy always had a hard time of it. At last, one day, when he was around hunting up bad boys to admonish, he found a lot of them fixing up a little joke on fourteen or fifteen dogs they had tied together in a long procession and were going to ornament with empty nitro- fi]ycerine cans tied to their tails. Jacob’s eart was touched. He sat down on one of the cans—for he never minded grease when his duty was before him—and he took hold of the foremost dog and turned a reproachful eye on wicked Tom Jones. But just then Alderman McWelter, full of wrath, stepped in. All the bad boys ran ‘away; but Jacob rose in conscious innocence and began one of those stately speeches out of a book which always begin, “Oh, sir!” 1n dread opposition to the fact that no boy, good or bad, ever starts a re- mark with “Oh, sir.” But the Alderman never waited to hear the rest. He took little Jacob by the ear and turned him around and hit him; and in an instant that good little boy shot out through the roof and soared away toward the sun, with the fragments of those fifteen dogs trailing after him like the tail ofa kite. And there wasn’t a sign of that Alderman nor the old iron foundry left on the face of the earth. Thus perished the good little boy who did the best he could, but didn’t come out according to the books. Every boy who ever did as he did prospered, except him, His case is truly remarkable. It will prob- ably never be accounted for, Mark TWAIX in 1870, Health and Morals. Among the papersread at the recent con- gress, perhaps none contained moré valu- | deavored to portray, what p or less supply of nutriment to those nerve or brain centers that make the man’s nature, his conduct, his character.” Catching but an inkling of the great truth which Mr. Dodson has so ably en- ent can fail to recognize a new responsibility toward her child. It becomes neceseary to give attention to an unknown science, the knowledge of the effect of physical condi- tions upon the child’s moral development. The child’s immoral tendencies, his bursts of temper, his fits of sulkiness are undoubtedly always directly traceable to physical conditions easily understood and possible of removal or at least of mitiga- tion if the parent will but give the time and energy to sifting out the real troubles. Well-borp_babies, with their physical wants intelligently attended to, are sure to be “good babies.” And when does the child begin to be *‘bad,’” if his environment is one which leaves him room to grow? Children are “bad” usually because they demand freedom, and, deprived of it, can- not but be an annoyance to the elders, who, in turn, become a far more serious annoyance to them. But set the “The Heir of the Farm”—By Knaus. “naughtiest’” of small boys or girls out on the sands of the sea- shore, with the infinite winds, the infinite sky and the infinite sea, and you will have no more signs of rebellion nor of irritabil- ity until you attempt to carry your small savage into captivity again. You need not even provide your ““troublesome’ little one with any tools with which to carry out his plans—not even with a pail and spade. If you will but remove all your restrictions— if you will but restrain your entire retinue of “don’ts”’—the child "will dig with his bare hands, and asks no more of life (be- fore he is hungry) than a chance to build “The Heir of the Farm”—After Knaus. [From a photograph by Marceau.} brave cities, toppling towers and endless, racetracks. The more energetic, the more deter- mined, the more fond of freedom our chil- dren are the more we find them an anxiety. And only because we have established an arrangement of physical conditions, which, whether they are or are not best for men and women, are illy adapted to the needs of growing children. Dio Lewis has said that children may live and flourish in gpite of bad conditions of every other sort s0 that they be supplied with” an abund- ance of pure air. Yet we shut them up in cities and grieve greatly that a majority of them die there. Theodore Thomas has said that children — TAKING THE DONKEY’S PICTURE. able suggestions than that of the Rev. Georze R. Dodson of Alamegda, entitled “Physical Means to Moral Ends.” “Char- acter,” says Mr. Dodson, “is the way your organism reacts to yourenvironment. It is peflee:? recognized that one’s conduct is changed by overwork, and that many a man’s moral character is different before and after he has eaten his breakfast. Itis impossible for a sick man to bea good man, for a man who is sick is not whole, is not perfect as ue might be. “Itiscoming to be understood that people are physiological machines, and that it is foolish to come with ideal moral considera- gous to people who are cold or tired or ungry. “/Character is changed by disease, some- times radically, and why not? It is easy to understand that a serious illness which 1 alters the physical being, may leave a greater or less pressure, may give a greater can only learn to sing well who sing hap- pily, naturally, without criticism, without seli-consciousness, without forcing. Any rational observer knows that the same rule will apply to the learning of anything; yet we shut our children up in schoo!l- Tooms, and the State provides that they be stuffed with information, while\it asks no question as to whether it may have been provided with food. It has been well said that the kindergar- ten system is yet in its incipiency. ay it soon grow with us, as in Germany, to the point of taking the children out of doors to learn their lessons. Why should not the teachers of San Francisco lead their charges to the neigh- boring hills for a first lesson in geography ? ‘What printed page can put before the chil- dren’s minds a picture like that which will be spread before them? And the whole- some exercise, the lively interest, the im- plied assurance that the earth is theirs and the fullness thereof, is it not a moral les- son, with proper physical conditions? Dorothy and Dolly. I am going to let you just only wear your nightgown this day. dolly, dear, an’ put some water an’ some nice crackers an’ a cherry down low where you can eat ’em all up your own self. Little girls mustn’t bother their mammas when their mammas an’ papas is goin’ to a ole Congress. Not any little small childrens must talk about they wants to go too, 'cause a Congress isa place what’s very bad for childrensto go to, an’ awful hard for mammas an’ papas to stay away from. My papa said he wouldn’t go to one the leastest bit, an’ then next day my really mamma telled him she looked down on the floor (I spose she was just a sittin’ up betop of the roof her own self) an’ she saw him standin’ up as hard as he could for three or six hours, an’ whole lots of other mans was standin’ up beround of him. An’ my really mamma said my papa an’ all the mans holded their mouths open most every minute, an’ clapped their hands an’ laughed an’ things when nobody wasn’t talkin’ to them, an’ nobody didn’t ask them to come. My papa says they can too come if they want to, an’ mans is just as good as womans ii their sleeves ain’t so big, an’ he could get at the Congress before the ladies is taked all the seats 1f she didn’t make him be late ’cause he had to stay home an’ put his little girl to bed. My mamma says she beclines to iscuss it some more, an’ won't my apa just step upstairs an’ bring ger most_prettiest hat, ’cause she don’t got no time. When everybody gets gone me an' Johnny Edson an’ some more childrens is goin’ to have a nice Congress over to their barn. Johnny is goin’ to try an’ bring scme pie, ’cause they. have pie an’' things. Con- gresses is a feast, cause my really mamma said so, an’ if we can’t get no sacred pie I spose rhubarb pie is most as good. e're goin’ to play circus an’ have lots of fun, an’ lpguess T'd betler put on your things an’ take_you along, too, my poor dolly, ’cause Johnny says his mamma says after the Congress lets out she’s to take care of him., Some folks has been sayin’, “Come, let us with our children live,” an’ I guess we ain’t goin’to have much more fun. If my papa wants to come to our circus, it's all right, ’cause he just only ties the ropes good an’ tight, an’ says for us to go ahead, an’ ’sides, he shows us how to turn summersaults, an’ he don’t say to be careful hardly any. But if all our really mammas is goin’ to take care of us we can neyer donuthin’, Idon’t want to be a good little girl an’ sit in a chair_an’ have a sore froat an’ a headache, would you, dolly? I like to dig holes over to Johnny's back yard, an’ get my clothes all tored, an’ have whoie boxes of cherries an’ things, ’cause everybody is gone toa Congress, an’ ain’t home to cook no bad ole hot dinners onto a stove. I just only wish that really great, big, ole éonm’ess didn’t letted out so quick, ’cause now I've got to go an’ be a little kindergarten child an’ stay into a ole school. It's pretty too bad for Johnny an’ all of us, ’cause when our mammas was gone we piled up heaps an’ heaps of things upstairs in Johnny’s barn, an’—you mustn’t tell nobody, dolly, dear, but we are got some nice matches hided out there, an’ when our mammas an’ things was all gone ’way just once more we was goin’ to have @ beautiful, beautiful, great, big bonfire up there, an’ we was goin’ to take hold of hands an’ dance all 'round it, singin’ an’ hollerin’ an’ havin’ beaps an’ heaps of fun. Aint you really, truly sorry that ole Con- gress letted out too soon, dolly, dear? Philosophy of Babyland. Alfred and Walter had permission to go for a walk. Presently Alfred (aged 5) re- turned home alone, and the following con- versation ensued: Mamma—Why, Alfred, where is your brother? Alired—He went in a boat, so I came home. Mamma—Don’t you think he was very naughty to go in a8 boat when he was for- bidden? No answer. “Tell me at once what you think about it.” Another pause. ‘“Well, then, I finks—I finks I don’t want to brag 'bout. myseif!’’ Little Tommy (to his playmates in the dooryard)—I'm goin’ right straight home and tell my mamma if you don’t let me play I'm God all the time that I stay over to your house. Now! Children’s motives should always be un- derstood. “Will,”” said Will's grandfather sternly, “did you pull up one of my little pear trees by the roots?”’ % “Yes, sir,” said the boy, with anything but a culprit’s face. 2 “Well, what did you do it for?” pursued the grandiather. “Why, grandpa, do .you want your cow to eat your green apples off your trees and get sick and poison the milk?’ ‘No, certainly not.” ““Well, I pulled up the pear tree because it was just the right size for a cow-whip and drove off your cow from your apple trees with it,” said Will,with offended dig- nity.—Harper’s Bazar. Little Johnnie was in tribulation one morning; prohibitions, great and small, met him at every turn. It was ‘“no’’ to thisand “no’’ to thattill at last he began to cry, angrily exclaiming to his mother be- tween sobs, “I wish ‘no’ was a swear word 50 you couldn’t say it!”’—Babyhood. Johnnie's father (sternly)—What were you fighting that bad boy for, Johnnie ? Johnnie—To keep from gittin’ licked.— Detroit Free Press. Freddie (aged 5)—I don’t think dogs take very good care of themselves, Grandpa—What do you mean by that? Freddie—Dogs bark so much I should think it would make them have sore throats. Frances, who hasrecently acquired some fowls, presents herself, all smiles, with a fresh egg in her small hands. “Where did you get that?” was the query. Frances (with enthusiasm)—My two pul- lets laid it! CALIFORNIA PRODUCTS. The Manufacturers’ Association Asks That They Be Supplied to All State Institutions. With a view to the protection of home industries, the Manufacturers’ Association has addressed the following letter to State institutions and departments: JUNE 1, 1895, Dear Sirs: Tt has heen called to the attention of this association that the various State insti- tutions will soon be calling for bids on supplies, and in the past the commissions of this State, on more than one occasion, have not given due consideration to Californis manufactures and products in vnllln¥ for these bids. This asso- ciation. therefore, feels called upon to write you and urge that, in all specifications here- after_submitted calling for bids for supplies of any kind, Californja manufacturers and pro- ducers be Fiven full opportunity to bid on all articles called for when the same &re manufac- tured in California. This association now numbers among the manufacturers and producers of California 650 members, which membership represents an in- vested capital in manufsctures within this State of $18,000,000 or $20,000,000. There is_ hardly anything that might be called for in_ these specifications that is not manufactured in California, and where quality and price are equal, we hope your honorable body will give California manufactured goods the preference. WE sincerely hope that you will aid us in this undertaking, as we consider it one of im- B ey on® Hiienof the SteTons efit to ever: . Yo 7, L R, MEAD, Secretary. very respectfully, Christian Union Mission, During the month of May the Christian Union Mission secured employment for forty- four men, & number being grovided with clothing; 1466 meals were provided, of which 1144 were given free; and 1726 beds were pro- vided, of which number 427 were free, Wheelbarrow on the Labor Question, A curious book written by a singular man. The author was born in London of very poor parents. He left school a mere lad, with the rudiments of an education, glad to work for a few shillings a week. He was a very young man when the Chart- ist movement arose in England and he flung himself headlong into it. Later he came to America and went to work at rail- road construction. He wheeled dirt in a barrow, hence his pen-name, Wheelbarrow, and he narrates with pride that he was an expert barrow-wheeler. Working his way along the line of the railroad that was building, when his job was completed at Richmond, Va., he ‘entered a brickyard. ‘While thus employed he studied hard and was admitted to the bar. After receiving his aiploma he went back to the yard to earn money to set him up in an office of his own. During the late war he rose to the rank of general, and bas since been a member of his State Legislature. In his preface he says: “‘Coming out of the labor strughgles of my childhood, youth and earty manhood, covered all over with bruises and scars, and with some wounds that will never behealed, * * ¥ Imay have written some words in bitterness, but I do not wish to antagonize classes nor excite animosity. I desire to harmonize all the orders of so- ciety on the broad platform of mutual charity and justice.” = His work is a series of essays on various of the problems pre- sented by capital and labor. They are full of sound, hard-headed common-sense and logic, interspersed with personal experi- ences and reminiscences of the greatest in- terest. The essayist is first and last upon the side of the workingman. He knows him, and knows the taste of bread that a man eats in the sweat of his brow. Never- theless there is a temperance and restraint, a certain fairness that comes of seeing all around the subject that does not always characterize the utterances of labor’s advo- cates. His essays are all brief, and cover a wide range of topics—‘‘Competition in Trades,”“Wages,” ‘“‘Money,” “Strikes” and ‘‘Monopolies”—he has a shot in his locker for each and all of the many dangers that threaten labor’s liberty, whether they lie in the camp of capital or of labor itself. His way of thinking is as independent as the man himself, and his book is eminently readable. [Chicago: The Open Court Pub- lishing Company.] The Armenian Crisis in Turkey. Frederick Davis Greene, M.A., for several years a resident in Armenia, has given us in this volume an account of the Armenian atrocities of 1894, with something of the eventsantedating them and the significance of the massacre. Mr. Greene was born in Turkey and has traveled extensively in the country. According to his showing, the case of the subject races in the Ottoman Empire is desperate, with no hope of re- form from within, and he declares that re- lief must come through interference on the part of the European powers. The real difficulty in Turkey, according to this author, is primarily not a conflict of races, or of religion, although both these ele- ments complicate the case. It is misgov- ernment. He does not use this word in its ordinary, mild sense, according to which there is ‘“misgovernmant” everywhere. Misgovernment, as it exists in Turkey, is an organization that breeds death and cor- ruption. No creed is exempt. Every race is attacked by it. The more apparent re- sult is outward impoverishment and ma- terial prostration. The more dangerous and deplorable symptom is the moral de- terioration of all the races affected. The case of the Armenians, Mr. Greene says, demands immediate and thorough atten- tion, but should not be allowed to fill the whole horizon in the Levant. Just now the blaze comes from their house, but no one can tell when it may result in a general conflagration. All the other Christian races, and the Mohammedan races, too are equally concerned. The book is well illustrated and gives a recent map of Tur- key in Asia, showing the sectlon com- monly called Armenia. [New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.] Socialism—What Is 1t? Is It Christian? Should the Church Take an Interest in It? A .very lengthy title for a very brief work. The little pamphlet is an address given by Rev. J. E. Scott before the Pres- bytery of S8an Francisco, and now printed by request. The reverend writer defines socialism on its economic side as a system of co-operation in the chief productive in- dustries, combined with an equitable dis- tribution of the products of industry. It has primarily to do with the practical rela- tions of man to man in the business of life, and considers the race, not as a multitude of isolated beings, but as a social body, its various members hnving a common reality of dependence one upon another. In answer to hic own question, ‘‘Is It Chris- tian?’’ he brings forward the testimony of various students upon the subject. He brings to the affirmative side such think- ers as Dr. Behrends, Laveleye, James Rus- sell Lowell, Professor Graham and Phillips Brooks. Christian socialism he declares to be, like Christianity, the cause of the poor man, and as such eve Christian should give it attention, to learn what widened application of the Gospel may be in it. Christianity has heretofore, he says, been applied to" individuals, but it is adapted to a kingdom, and a kingdom means organized society and a state. “Jimmy Boy.” The women who were little girls twenty- five years ago will recall the delightful “Prudy Books” thatgave them such pleas- ure and were the most welcome of gifts at Ckristmas and on birthday anniversaries. With what delight they were read and re- read. Happy the child of these women whose mother has treasured the relics of her juvenile library! But now “Little Prudy” has grown up and we haye another story by Sophie May, whose fertile pen brought Little Pru Ly herself into existence, Boy is cne of Little Prudy’s children, and his quaint_sayings and doings are proof that Miss May still retains her old charm in writing for children. Jimmy Boy lives in California, Little Prudy having left her home back in Maine for another on the Pacific Slope. Little Jimmy will be wel- come to Californian little folk because of his own dear self, and older readers yet will grant him a welcome because of the early associations and memories that true men and women never outgrow. [Boston: Lee & Shepard. For sale by William Doxey, SBan Francisco.] Common Land Birds of New England. Professor Willcox of Wellesley College has written this little book primarily for the use of his classes in field study. It deals with the common land birds of New England, but as birds, like their human brethren, decline to be bound by geo- graphical lines, the book will be found useful in studying most of the birds in any locality in North America. Studenis in California will find it of no little use in identifying “that bird yonder on the fence,” and a litile knowledge of the identi of the feathered folk we encounter on our rambles adds materially to our enjoyment of out-of-door life. The book is of con- venient size io c.rr{ in the ficcket, and contains an artificial key to the common species of New England birds that will be found very useful in placing any bird ordi- to be encountered. The main guide to finding, in the key, is color—which is, after all, the only e uninitiated can follow. A bird ora flower to such a learner “Jimmy is red, blue or yellow. Peculiarities of con- formation, of feathers, beak or petals do not strike him as significant, and are at first of little use to him in identification. Profes- sor Willcox’s little handbook will be found to occupy a wide field of usefulness. [Bos- ton: Lee & Shepard. For sale by William Doxey, San Francisco.] A Compact Encyclopedia. In addition to the great encyclopedias of many volumes in which attempts are made at a comprehensive summary of human knowledge there is a general need for smaller and more convenient works of a similar character to serve for ready refer- ence rather than for study. Such a book is the ‘‘Globe Treasury of Universal Knowledge.” Within the compass of 431 pages it comprises a large amount of gen- eral information on a wide variety of topics. It is arranged in a narrative form for convenience of general use, and a con- secutive and progressive resuit is attained by beFinning with the ‘‘origin and cause” of all things and following a natural sequence through successive studies of science, language, literature and history from the earliest ages to our own times. Each item of information is put in the shape of question and answer for the pur- pose of defining clearly the meaning of each paragraph and facilitating research. In addition to these advantages of form the book is provided with an analytical index, which enables one to turn immedi- ately to the page containing the informa- tion desired. [“The Globe Treasury of Universal Knowledge”: G. W. Dilling- bham, New York.| Dr. Gray’s Quest. This is the last work of the late Francis H. Underwood, LL.D., whose “Quarbin” and handbooks of English and American literatures have made his name familiar to many. “Dr. Gray’s Quest”” is not a par- ticularly strong story, and one might ques- tion the ethical purpose of the writer, whose most detestable character, ethically considered, fares from first to last about the most comfortably of any of the people in the book. But the story is interesting as giving a clear and tangible picture of the time and people dealt with. For the time being the reader lives and has his being among New England people in the early forties. They are not old maids, nor an%vuuh wells of English defiled as Mary E. Wilkins and the rest of the modern dis- coverers have presented to us, but they are all genuine. The habits of thought, ex- pression and life of moderately cultivated Americans of that period are very clearly portrayed, and the atmosphere in which they live, while perhaps a trifle common- place, seems far more real than most of the amazing realism of the modern school. Boston: Lee & Shepard. For sale by William Doxey, San Francisco.] Oriole’s Daughter. Jessie Fothergill has told a strong story in this tale of the life of a young Italian girl. The natural daughter of an Italian gentleman who has fallen upon hard times, Fulvia Dietrich, legally, ard by the iron traditions of her nationality, was as abso- lutely the mother's chattel and at her mother’s disposal as though she had been a basket of oranges. This mother disposes of her in marriage to a dissi}mbed brute of an Australian. The girl’s life is a might- mare for a year, then she hardensto acold, soulless woman of the world. Her hus- band becomes a hopeless, helpless invalid, and durine her attendance upon him_love comes to her. The problem presented her, between the brutality of her husband an the importunities of her lover—and her manner of meeting it, form the main motif gfli '(.)he]novel. [New York: ,Lovell, Coryell 0. The Story of Patriot’s Day. Thisisan account of the first celebra- tion, in April, 1894, of Massachusetts’ new legal holiday, “‘Patriots’ Day,” which oc- curs on the 11th of April, and is intended to supersede the day of fasting and prayer, | the annual appointment of which has been abandoned in that State. The little book contains suggestions for tha celebration of the day by the school children, and the author, George J. Varney, has crowded a vast deal of patriotism between the two red covers. [Boston: Lee & Shepard. For sale by William Doxey, San Francisco.] CI R WITE THE PERIODICALS. A KENTUCKIAN ON KENTUCKY USAGE.— The Southern Magazine has changed its name to The Mid-Continent and comes out in a new yellow cover, in illustration after the manner of Audrey Beardsley at his yellowest. Among the editorial utter- ances in this issue is an article that, com- ing from a Kentucky writer, and appear- ing in a magazine that caters to a wide circle of Kentucky readers, is at once courageous and full of promise. The in- stance treated of is the recent killing of Sanford by Goebel at Covington. These two men, both in high position, engaged in a po'litical controversy through the press. In the course thereof Goebel ap- plied to his adversary language which, the fid-Continent writer says, ‘‘no man of decency should ever use, yet language very commonly in uSe among Kentucky gentle- men toward their enemies, which most of them feel, too, that they must resent when applied to themselves,” The writer then goes on to declare that there is probably no other civilized community w%ere the law regards the taking of human life with such stolid indifference as it is regarded in Kentucky. He continues: To hear these affairs discussed by many of the best men in the State wonld simply amaze one not used to the conditions that obtain in Kentucky. They lament the necessity for kill- ing a man, but when the necessity arises, and, according to Kentucky sentiment it is continu- ally arising, one must either kill or be consid- ered a poliroon. Where a Kentuckian is in- sulted—and he is the eesiest man in the world insulted—he only calls hisassailant to account. The assailant, to maintezin his honor, must answer that he meant what he said or did, whether his words or actions were idle or not, and to maintain his honor the person assailed holds him “personally responsible.” Here is the necessity for one to kill the other, and, ordinarily, it is done, for in & personal en- counter the work is rarely. left unfinished. If an examining court should by any chance bind u})rominen! murderer over to an ensuing term of the Criminal Court, and if by chance the Grand Jury should return an indictment against him, all interest centers in his trial. o The newspapers give daily accounts of what good he has done gn the past, of the flowers and tokens of sympathy he is daily in receipt of from those who have received bene- factions at his hands, and by the time the trial glegins his acquittal is almost a foregone con- on. TeE ArnaNtic MoNTHLY.—The reader who, like Bunthorne, Does not sigh for all one sees That's Japanese, 'Will find more that is readable in almost any other periodical than the Atlantic Monthly. Asan exponent of the Oriental cult, however, the magazine may be said to do its work thorougnly. There is in the current number an article on “A Pil- grimage to the Great Buddhist Sanctua; of Northern China,” by William Wood- ville Rockhill, and no less than three articles on Japan and recent books on Japan. Of these articles the most im- Portant—by far the most delightful of all n the mafiinzine—ls Lafcadio Hearn’s “In the Twilight of the Gods.” Mr. Hearn has a peculiar and loving sympathy not merely for the Japanese, but for afi the Eastern p_e:&l;s and the compar~atively un- known civilizations, He writes with a deeper insight into their mental processes than perhaps almost any other traveler of to-day. In “In the Twilight of the Gods” Mr. Hearn views a collection of Japanese gods, and tentatively lifts a mental curtain to afford a flecting glimpse of the Buddha ideal that is as suggestive and inspiring as it is unusual. Virna Woods, a Californian writer who is beginning to win a name for herself, has a poem, “On the Oregon Ex- press,” in this number of the Atlantic. ScrisNer's Macazive.—The bicycle craze receives full and substantial treatment in the current Scribner’s. It is treated from the standpoint of the expert. The woman and the bicycle has full, consideration and the social and medical aspects of the fad are given due attention. Even one who is not yet avictim to the wheel rabies cannot but be interested in these articles, and it is a pleasure to note that expert, physician, society woman and man, aiike all protest against the absurd, s doubled- up-over-the-hand by would-be * done probably more than anything else to disgust many penFle with the wheel and its = devotees. Mrs. Humphry- Ward’s novelette increases in interest—a quality usually lacking in Mrs. Humphry-a'ard's work, and Mr. Robert Grant’s stultifying work on “‘The Art of Living’’ treats upon the use of wine in a way calculated to be of some value to a very small minority of people. An article on “Chicago, Before the Fire, After the Fire .and To-Day,” by Melville E. Stone, constitutes the principal interest of the number, and the ‘“‘History of the Last Quarter-Century in the United States” deals with the eventful centennial year, 1876. NEW TO-DAY. The Expulsion of the Chinese From our shoe factory dates back over 30 years. We had bought out a factory in which Chinese were extensively em- ployed. They were promptly replaced by white men. The shoes that we are now selling at retail at the same prices paid by retail dealers— FACTORY PRICES—are made by your fellow citizens whose wages belong to the money circulation of our own City. ROSENTHAL, FEDER & CO., WHOLESALE MAKERS OF SHOES, 581-583 MARKET ST. Open till 8 P. . Saturday Nights till 10. FREE TO WEAK MEN K NEVER PERSONAL FAILING WEAKNESS (URE FOR ALL IN MEN To men who suffer from neryous debility or any of the many signs of falling manhood and who have been wasting time and money on doctors and cheap electric, or so-called electric beits, any means that will assure the much desired cure will be hailed as a God-send. Repeated failure makes one skeptical, and it 1s to this class of men that Dr. Sanden makes this offer: A FREE TEST. It you will send your name and address, with & statement of your case, so that the proper power of belt may be chosen to warrant a cure, & Dr. San- den belt will be sent you by express, with Instruc- tions to the agent (0 permit, free of charge, a thor- ough test of its power, after which the beit may bo accepted and pald for if satisfactory, or returned if not, at no cost to you. Send for the book “Thres Classes ot Men,” which gives full particulars, free upon application. A LATE CURE. TOANO, NEV., May 6, 1895. Dr. A. T. Sanden—DEAR StR: Complying with your request for a report of the effect of your belt 1 would say that I felt its curative powers from the first day that I wore it. Before 1 bad the belt L suffered with my back, 8o that it was with diffi- culty that I could stralghten myself out when working in a stooping position. Now I can work all day bent double without the slightest incon- venlence. I wonld not sell my belt for ten times its priceif Tcould not get another. This cure was pertected in less than two months. Respectfully, JoSEPH WALKER, Tosno, Nev. THIS MAY SAVE YOU. Every young, middle-aged and old man should read OUR NEW PAMPHLET, fully illustrated, and containing hundreds of ‘tesiimonials from every State, With NAME AND ADDRESS in full, 80 that you can write or see them and satisfy your- self of the truth of our statements. is sent SEALED FREE, upon application. Largest Elec- tric Bell Manufactory 14 the world. address Pacific Coast office, SANDEN ELECTRIC COMPANY, Council Building, Portland, Or. 2 OBDONTUNDER DENTAL PARLORS 8153 Geary, bet. Larkin and Hyde. R L. WALSH, D. D. 8, Prop'r, directly opp. atoga Hall. Price li Extraction (painless)25¢ Bone filling 50c: Amal- fnm,?lngk‘g()c: R“rlkd glfll- ng $1: Bridgewor : Crbwns #5: P $7; Cleaning $1. k&very operation guaranteed. 23~ On entering our parlors be sure you see DR. ‘WALSH, personally. People in San Francisco. The unequaled demand for Paine’s Cel- ery Compound among the people of this city 1s but one Index of the great good It is doing. There are many in San Francisco whom it has cured of serious fliness. Paine’s Celery Compound makes people well who sufter from weak nerves or impure blood.