The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 18, 1919, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

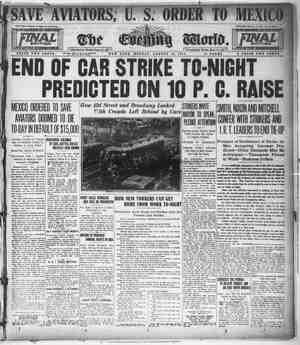

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

| SRS How Seattle Bou ht a Traction System Eastern Company Unloaded Llnes for $15,000,000 When War Demanded Street Car Efficiency for Sh1pbu1ld1ng Plants BY E. B. FUSSELL EATTLE is the first large city in the United States to own its street car system complete, It owns and operates 500 street cars daily over 200 miles of track. For this the city paid $15,000,000. As this is written, the system has. been in opera- tion for four months under pub- How Seattle happened to go into the lic ownership. street railway business is an interesting thing to consider. Seattle is a city of around 350,000 people.’ many years its public utilities, and those of most other Washington cities, have been in the grip of For great corporations. During the last 10 years there has been a fight against the corporations, led on behalf of the people by men like Robert Bridges of the Seattle port commission and Oliver Erickson, Seattle city councilman. Erickson and his followers carried on the fight that led the city of Seattle to go into the light and power business for the benefit of its citizens. Elec- tric rates were cut to a third or one-quarter of what they had been. Bridges and his followers succeeded, eight years ago, in having the port district of Seattle created, with provision for vast public-owned elevators, warehouses and wharves. The effect of the in- creased facilities for shipping and other business for one thing made Seattle prosperous. The very business men who had fought “public ownership” on the ground that it could “never be successful” made more money. But the establishment of the elevator and warehouse system also had a big effect outside of Seattle. The apple growers of the Wenatchee and Yakima districts, the wheat growers of the Palouse and other farmers found that for the first time they could borrow money at 6 per cent on their produce, without being forced to sell on a low market as soon as they harvested. The fact that the Seattle city light and power system was so successful in reducing rates and that the port of Seattle was making the city prosperous and at the same time was helping the prosperity of the -farmers of the back country, meant a great boom for the principle of public ownership. The Seattle street car system at this time was operated by a firm of Boston engineers, Stone & Webster, for the bene- fit of eastern stockhold- ers. Stone & Webster furnished light and power to Seattle before the city built its own plant. The city plant naturally cut deeply into the private busi- ness of the Boston firm. Stone & Webster kept on operating the street cars—but they could see that the next step would be municipal ownership of transportatien as well as power. PAPERS AIDED FIGHT ON PUBLIC OWNERSHIP Stone & Webster determined on a great campaign against public ownership. In this they had the help of the two largest newspapers of Seattle, the Times and the Post-Intelligencer. Both of these papers have been under obligations to the great financial interests with which Stone & Webster aie allied. The late James J. Hill personally loaned money to Alden J. Blethen, founder of the Times, to help him start his paper, and the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads for years held the bonds of the Post-Intelligencer and reported them on their books. There was a chance that the legislature might do something along public owner- ship lines. Stone & Webster sent some of their cleverest attorneys down to the capi- tol at Olympia. They rented one of the Jargest mansions in the ecity, stocked it system. equipment. with wines, liquors and. eigars, hired a corps of Japanese servants, wined and dined legislators and “entertained” them at poker games, at which the Jegislators frequently won large sums. The Times and Post-Intelligencer daily preached against the “wastefulness” and “folly” of public ownership, the lobbyists kept busy and the legislators fell into line. At the session of 1915 Stone & Webster and the anti-public ownership crowd generally were so successful that they not only kept the legislature’ from going any further into public ownership but prevailed upon the legislators to pass a law in- tended to cripple the Seattle port commission and eventually to put the entire port district out of commission. But after the leglslature was over the citi- zens of Seattle, aided by the farmers of eastern Washington, circulated referendum petitions which tied up the law to kill the port district. When the law came before the people for a vote at the election of 1916 the only contest was to see whether the citizens of Seattle or the farm- ers of eastern Washington would roll up the biggest majority against the law and in favor of public ownership. At the legislative session of 1917 Stone & Web- ster changed their tactics. They tried no longer to kill what public ownership there was in Washington. They merely tried to protect what ownership they had left in their street car system. They kept the legidlature, as before, from doing anything to further or promote public ownership. They were strictly on the defensive. But when the United States entered the war, con- ditions changed again. Seattle became the great headquarters of the country for shipbuilding and spruce production. Workmen flocked to Seattle by the thousands, but even their numbers were not enough to supply the demand and wages jumped from day to day. Stone & Webster had been making dividends in past years by underpaying workmen and giving poor service. They had been able to pay dividends, Above—Some of the property of the Seattle municipal street railway The city owns approximately 500 cars like those shown here. New cars of modern type are being ordered to replace antiquated Below—One of Seattle’s busy downtown streets, showing the congestion of traffic that was a matter of daily occurrence until the city took over the street car system. corporation was unable or unwilling to give the service led to the agl- ; tation that resulted in the city taking over the lines at a fancy prlce. P PAGE EIGHT T — SR R st e N TN 5 S e T TR TR T g i s 4 U ST R T S T T S AN SR T P e ST T T AR R AR AT e I SR S R NIRRT J.‘,wa 9 j‘“f“a The fact that the private not only on the value of their property, but on some millions of “water” injected into their valuations by setting fancy prices on power sites and the like. But under war conditions they could not keep on doing this indefinitely. They had to advance wages and give their employes something like fair play. The demand went up for better service. Stone & Webster failed to give it. Workmen, bound from distant parts of the city-for the shipyards, were held up on their way to work for 20 minutes, 30 minutes or an hour. Long lines of stationary street cars blocked -downtown traffic. during the hours when they should have been moving fastest. The situation was intolerable. The démand for public ownership rose again. Stone & Web- ster, the Times and the Post-Intelligencer, which had tried first to kill public ownership, then to hold their own against it, saw that they were up against a losing fight. There was just one way for them to save themselves. That was to jump aboard the public ownership move- ment and try to save something out of the wreck. OPPONENTS OF PLAN CHANGED OVERNIGHT And that was just what they did. The Times and Post-Intelligencer, which had been the bitterest foes of public ownership, turned an about-face over night. “Let’s take over the street cars,” they cried. “The city must operate them to give the service.” The real public ownership men of the city saw what was coming. It was to be an attempt to un- load a ‘worn-out system on the city at an extor- tionate price, under conditions that would make successful operation next to impossible. It was planned so that the enemies of public ownership might, some time in the future, point to Seattle and say: “That city tried to run its own street cars. See what a mess they made of it! That proves that public ownership is all wrong.” The city authorities proposed to Stone & Web- ster that the city take over the street car lines and operate them to give service to the people of Seattle and to help the government win the war, and that the city guaran- tee to the company the .average earnings that the company had made during the past four years. This was an emi- nently fair proposition, rather too favorable to the company, if anything, for wages, when the lines were taken over, were nearly double what they - )] were four years before. | : “Nothing doing,” Stone & Webster replied. “We want to sell the line outright and we want our price for it. The price is $15,000,000.” And with the Times and Post-Intelli- gencer calling for immediate public owner- ship, with the public calling for better street car service at any cost, with the United States government and the allies calling for more ships to meet the German submarine menace, and with all of these elements, knowingly or unknowingly, working for the interests of Stone & Web- ster, the city of Seattle took over the street car lines at Stone & Webster’s price, $15,000,000, issuing 5 per cent bonds for this amount, guaranteed by the - gross earnings of the car lines. The only ones who fought the taking over of the street car lines were Oliver Erickson and his group, the real pioneers of the public ownership movement. They felt that a crime was being committed in the name of public ownership. Besides $15,000,000 for the street cadr lines the city, in taking the lines over, agreed to pay Stone & Webster 1 cent per kilowatt hour for the power used to oper- ate the system. This is a high rate for power in a country where nearby streams provide millions of horsepower of energy. R S