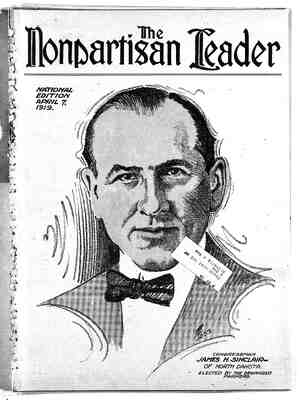

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, April 7, 1919, Page 12

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

1 i { L i N A\ N N BY ELISABETH MILLER LL my young years I spent on a farm, most of them on a Dakota farm. Five years before Dako- ta territory was divided into twin states, our family, transported westward by one of the “accommodation” trains of a hastily laid railway (I assure you, it had really no accommodations), set- tled on a prairie “homestead.” We knew the sunny, treeless stretches and strove to break them by planting the seeds of the box-elder and cuttings of cottonwoods around our little farm- house. We knew the prairie winds, driving myriads of tumbleweeds up and down the earth in those early days when the settlers were turning the sod and leaving it to mellow for the first year. The hot winds of sum- mer, drying and blasting the green- ness of the spring, we knew and feared—the “rainmakers” of the terri- ble years of drought, seriously en- gaged by the county administration to experiment in bringing moisture from the skies to the relief of perishing crops, were neighbors of ours—the farm of the head rainmaker cornered our own, EXPERIENCE ON THE PLAINS We knew—shall we ever forget?— every aspect of the wide wheat fields; the first tender showing of green across the black soil in the spring, in- creasing to a thick carpet like velvet; the subsequent advance to a “good stand,” the heading out, the filling, ripening,. harvesting, shocking, stack- ing, threshing, hauling to the grain elevator and the mill; or, as happened all too often, the blasting by drought or rust or—I have seen this happen to perfect, golden fields into which the harvesters were just ready to.go— total destruction by hail. We knew the pinching months that followed the failure of the crop until a crop could be raised again. Worse, we knew the disappointment, even when crops were good, of low prices, high rates of interest on borrowed money, debt for provisions, debt for seed, debt for machinery, "all the year’s crop gone for last year’s debts, and debts for the bare necessities mounting again. I had almost forgotten . those pioneer experiences, rendered, I may say, endur- able and in a measure joyous by real neighborliness on the part of the settlers and a perennial hope of the future. But hearing, here in the city —1I have been in the city now for almost 20 years, with only occasional visits back home—of the rising farmers’ movement of the Northwest, brings it _all.back. They are true succes- sors of the pioneers, these farmers of today. ~As their predecessors subdued the soil, and this done, “branched out” to other crops than wheat and to the raising of - stock, so that if one fail- —_— Y N\ ed there might be others to de- pend .on, they are subduing other powers, in order that prices shall be just, rates fair, the opportu- nity to buy and sell for themselves be vouchsafed the producers of the foodstuffs of the world. “According to those who tell the story, the farmers of North Dakota had been patiently working for years to overcome a system of undergrad- ing, underweighing and dockage of grain imposed upon them by nonresi- dent boards of trade and chambers of commerce through the local buy- ers. They began by establishing co- operative elevators for the handling of their own grain, but though this eliminated the local buyer, they had ultimately to sell to the same monop- olies. So they decided that they must own the terminal elevators as well. This demanded credit for which they turned to the state. But the consti- tution of the state, framed by the railroad companies 30 years ago, for- bade such use of credit. After a four years’ struggle, the farmers suc- ceedéed in getting the constitution changed. Now our co-operative or- ganizations can borrow -money the "same as any other business organiza- tion, they said. But their amendment provided no money to carry it out. The defect could be remedied by the state legislature, and the farmers asked that body to take such action. ‘But after the manner of legislatures, it failed to grant the request. When the next legislature met, two years later—this was in 1915—the farmers visited it in a body to ask for what they wanted. A half-intoxicated member of the lower house undertook to answer them in a tirade in which he told them that making the laws was none of the farmer’s business and insolently advised them to “go home and slop the hogs.” This final indignity was ‘to the farmers the signal to take things into their own hands. They formed an association, voluntary as to member- % ) 2 '//m s r////m ship, for the purpose of obtaining po- litical power. They did not organize a new: party, but in each political dis- trict selected a man pledged to their legislative program and by their united influence made him the candi- date of the party to which he be- longed. Then they all, of whatever party, gave him their vote. As a re- sult, the North Dakota elections of 1916 sent farmers to all the state of- fices except treasurer and to 87 of the 116 seats in the lower house. Though there remained a holdover majority against them in the senate, they were able to adjourn the 1917 session with no less than 30 laws to their credit, including an excellent co-operative law; a weighing and grading law that saves hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to marketers of grain; a guarantee of bank deposits la 7; a law standardiz- ing the rural schools of the state— the little old prairie schoolhouse such as I went to school in were still being used, and courses of study were no- toriously backward—and laws estab- lishing evening “schools and county agricultural - and training schools; granted partial woman suffrage—the farmers are still a mite conservative there—established dairy, welfare and highway commissions and regulated taxation in a number of beneficial ways. - Though their most important -bill was killed in the senate, 2 measure which- purposed to amend the. con- stitution so that an imposing' pro- gram of public ownership could be enacted into law, this session of the legislature of an almost exclusively agricultural state became the sensa- tion among political circles of 1917. OVERCOMES ALL OPPOSITION IN 1918 The Nonpartisan league has met the tremendous united opposition of the “predatory interests” ever since. But opposition has stimulated effort. In the campaign of 1918 the farmers adopted the expressive slogan, “We’ll ] HELEN TOWNSHIP LEAGUE CHORUS | The young League folks of Helen township, in McLeod county, Minn., have formed a League chorus. They have good times practicing by themselves and especially good times singing at the League meetings. In describing this chorus Mrs. Ben Harpel says: pleasure they have in rehearsing for these occasions is perhaps one of the means to solve the question of how to keep the boys and girls on the farm. % PAGE TWELVE : 3 “Further, the “Farmers Their Own Legislators ‘ An Interesting Story of the Nonpartisan League Movement, Published in the February Issue of the Social Progress Magazine stick,” and under it captured every * North Dakota state office from the governor down, the judiciary and both branches of the legislature. They also adopted 10 amend- ments -to the state constitution practically making it entirely new. By these amendments the people of the state may use its credit to build cold storage plants, grain elevators and packing plants, to establish banks and hail insurance, to purchase telephone and telegraph systems and to <utilize waterpower. In other words, the state may now be its own banker and middleman. The 1919 legislature is now in session. It is a bit early to .proclaim’ re- sults, but they are certain to prove momentous. OTHER STATES LINING UP The north star of the farmers’ movement, an enthusiastic supporter of the League calls North Dakota, and it is true that organized farmers of surrounding states are swinging in behind North Dakota’s leadership. Early in the movement it was recog- ‘nized that not much could be accom- plished by winning one state alone. So the Nonpartisan league was made a national organization, with head- quarters at St. Paul. The greater part of North Dakota’s products find market in Duluth and the Twin Cities; Minnesota must be won. So with surrounding states. An organi- zation campaign carried into 13 states —dubbed the original 13—has result- ed in over 200,000 members. five states outside of North Dakota where the League entered the 1918 political campaign—Minnesota, South Dakota, iColorado, Montana, Idaho and Nebraska—the farmers helped to elect, in spite of war handicaps, blizzards on election day, lack of help on the farms and the “flu,” two United States senators, one congressman and. 110 members of state legislatures. While holding the majority vote in none of these states, they are represented by a vigorous minority that prophesies well for a majority in 1920. In states like Minnesota, Montana and Idaho, where organized labor plays an im- portant part and where the percentage of farmers is smaller than in North Dako- ta, it is the pelicy of the Lgague to combine forces with state federations of labor. The workers in the mines and factories, so rea- son the farmers, are many of them men and women—sadly enough children, too—who have been driven from the farms by overhard conditions. Farmers must have the prod- ucts of the factories; laborers must have the food from the farms. Why not co-operate to establish, means of ex- ch}mge that will reduce the tribute now paid to the mid- er-labor candidate,” is a new one, but indications are that it, too, is' going to “stick.” In the dleman? The phrase, “farm- o) £ <, ey Y % = '—"i‘#' i | -l e