The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, January 14, 1918, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

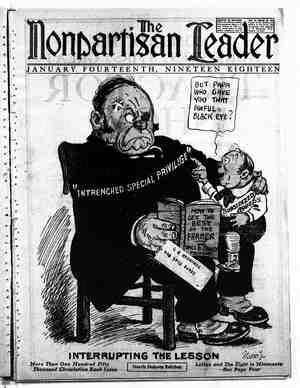

i RN A s é.._f Loftus and The Fight in Minnesota Also Something About Ignatius Donnelly and the Farmers in Politics in the Old Days e Fourth Installment of the Historical Series. ‘ ‘ ' BY E. B. FUSSELL members of the legislature, judges, coun- ty officers—everyone except state offi- cials and congressmen—on a nonpartisan ticket. They don’t file for office as Republicans or Demo- crats, but just as Jim Jones or Bill Smith. But is Minnesota really as nonpartisan as the law says? Do Republicans and Democrats, wets and dries, farmers and politicians, dwell there in perfect peace and amity? Look at the history of the people’s fight in Minnesota, and especially at the history of the farmers’ fight and see! Minnesota is largely an agricultural state, but by no means entirely so. Besides the three big cities, Minneapolis, St. Paul and Duluth, with their large labor population, there are the iron mines and the lumber camps in the north. These has never been a time when the farmers and the labor men of the large cities, combined, could not have controlled the government of the state. But the fight of the Weyerhaeuser and allied timber inter- ests, the Steel trust operating in the iron ranges, the big milling and railroad and traction interests of the Twin Cities, has always been, first, to keep farmers and labor from organizing, and second, to prevent them from combining when organized. And in this fight Big Business to date has been largely successful. DONNELLY PUBLISHES “ANTI-MONOPOLY"” The history of farmers in Minnesota really be- gins with the Granger movement in the 70’s. The i farmers became more active when the Farm- ers’ alliance was or- ganized in Minnesota in 1886. Ignatius Donnelly became a leader, not only in Minnesota, but nationally. He had been in politics before as a congressman and was lieutenant-governdr at the time of the Civil war. But Donnelly was not content to train with the old crowd. He was an independent and a striking figure, according to his old time friends." “Brainy, enthusiastie, a -wonderful orator,” are some of the things _that the old timers say about Donnelly. In 1874 Donnelly started the publication of “Anti-Monopolies,” a publication that was the leader in the progressive thought of Minne- sota of that day. In 1888 Donnelly and a number of other Alliance men were members of the legislature, although the farmers had not gone into politics as an organiza- tion. Donnelly attempted to organize them into a political group within the Republican party. But the treatment they received in the senatorial fight of that year made them determine on a further step and in 1890, Loucks of South Dakota sug- gested “independent political action,” and the Minne- ‘ INNESOTA is a nonpartisan state. Any-' politician will tell you that. They elect Donnelly sota Alliance held a state convention to put a full ticket of their own in the field. "Donnelly seemed to be the choice for governor. But he had been in politics 30 years. A hard fighter, denouncing corruption and favoritism wherever. he saw it, like every fighter he had made many ene- mies. There were seven candidates. At the end _.of the second ballot Donnelly was leading the field _ but lacked a majority. At this point the farmers made a wise decision, the same decision that was made in 1916 by North Dakota farmers when they made up their state ticket. They determined to throw all candidates to one side and to choose as ' their standard bearer a man who never had been in politics before. One the third ballot Donnelly and all other candidates withdrew and Sidney M. Owen, editor of a farm paper, a comparatively new comer to Minnesota, was nominated. . Owen, like Donnelly and most of the other old ‘leaders, is dead now.- He is described as a'solidly ‘built man with iron-gray hair, not an orator like The fourth article in the Leader’s his- tory of the struggle of the farmers for democracy and justice; in the states where the Nonpartisan league is organ- izing, deals with Minnesota. It is pre- sented herewith. The story of the farmer in polities in Minnesota is close- ly connected with two great leaders, Ignatius Donnelly and George Loftus. Donnelly fought and died years ago; Loftus more recently. The details of their leadership of the farmgers are in- tensely interesting. Readers can start this series of fact-stories with any issue —each article is complete in itself.” You will be watching for the history of the “farmers’ fight in YOUR state, but you will also want to learn the facts about the fight for the last 30 years in THE OTHER STATES. If you have not started the series, begin with this issue. Donnelly, but a good speaker, a fine, square, upright type of man. In the years that followed, Donnelly and Owen were the two leading figures in the Alliance movement, which became the People’s party two years later. BI-PARTISAN MACHINE AGAINST THE PEOPLE But all of Owen’s uprightness, the fact that he had never been tainted with politics, the fact that he had no enemies, did not preserve him from the breath of scandal, spread by the politicians repre- senting the Big Business interests, who never could stand it to see the farmers running the government- of Minnesota. Owen was represented as a man who wanted to wreck the credit of the state. Twin City papers (the same ones that are fighting the Non- partisan league now) had cartoons showing him as a devastating cyclone threatening to destroy Minne- sota. It would serve no purpose to tell in detail of the struggle of the farmers. They had no campaign funds and almost no papers that were friendly. They did not have the effective co-operation of labor. They fought and lost and fought again. Owen was de- feated in 1890, though securing 58,000 votes, within 30,000 of the votes of the winner. Donnelly ran in 1892, running 10,000 votes ahead of Weaver, the Populist presidential candidate, but lost. Owen ran again in 1894., This year it is said that he would have won but for the fact that the Democrats, who had agreed to put up no candidate, put a man in who got just enough votes away from Owen to give victory to the Republican. The farmers found that the fight between the old parties was in reality largely a fake—there was a bi-partisan machine willing to go to any, length in the interests of Big Business to defeat the farmers. However, the farmers made their strength felt. They elected many members of the legislature and three congressmen. They did more than this. They forced. the old line politicians, through fear of the farmers, to grant two of the principal reforms that the Alliance was seeking. 'ALLIANCE GOT FARMERS TWO-BIG REFORMS “The Alliance secured two reforms that alone justified its existence,” Colonel R. A. ‘Wilkinson, who watched the fight in those days, told the writer recently. 2 “One was the state manufacture of binder twine at the state penitentiary. Minnesota was the first state in the country to do this. “The other was a grain and warehouse inspection law. Before this law was passed there was a ‘leak- age’ of 12 to 15 bushels on every carload of grain shipped to Minneapolis. Anyway, the scales at the Minneapolis elevators showed that much less than. when the car was weighed at-the elevator. After the law was passed the leakage ran down to be- tween a bushel and a bushel and one-half a ecar. The railroads must have done quick work ‘in fixing up their cars. Or else they changed the system of weighing.” - & ISk ; - PAGE FOUR' After fusion in 1896 the Populist party rapidly faded away and the farmers’ movement with it, until a dozen years ago. Then a new figure appeared in the limelight. It was George S. Loftus. Loftus, like Donnelly, was a hard .fighter, “one who neither asked nor gave quarter,” his best friends describe him. He had never been in politics. He started out as a newsboy in Minneapolis in 1882, became a messenger in a railway freight office, working up to be assistant to general freight agent. Then he went into the grain business. Loftus knew something of the system of unfair rebating practiced by the railroads when he worked for them. He got a further taste when he started iu the grain business. Loftus owned an elevator at. Stillwater, from which he shipped grain to Duluth. His freight rate was advanced from 5 to 71 cents. He found that a rival firm was getting all the busi- - ness and further investigation showed that the rival, through influence with the railroad, was still enjoying the 5-cent rate. Loftus started a fight, a fight that he finally won, but not until his own busi- ness was destroyed. s LOFTUS TAKES FIGHT TO THE LEGISLATURE Loftus uncovered other secret rebates that big elevator companies were receiving from railroads, enabling them to put smaller firms out of business. As the result of his exposures the Great Northern railroad was fined $15,000, the Wisconsin Central $20,000 and the Omaha $22,000. Loftus found that small shippers were imposed upon by being left without cars long after they had ordered them, and their business being ruined by this delay, although they were charged demurrage if they held the cars an hour after the time allowed by the railroads. He urged the passage of a reciprocal demurrage law, which would penalize the railroads for their delay the same as shippers were penalized. State after state adopted this law, owing to Loftus’ fight, though finally the supreme court practically knocked it out by ruling that it could not apply to interstate commerce. In 1905 Loftus started his fight for a reduction of freight rates before the Minnesota legislature. He found much opposition among members of the legislature, and it wasn’t confined to any one party, either. The bi-partisan railroad machine was at work. It was the line-up of the farmers on one ° side and Big Business on the other. Loftug got an :lnvestigation started, that was all that could be one. LOFTUS SUCCESSFUL IN HIS BIG FIGHT The next year, when it was time to elect the 1907 legislature, Loftus went out in advance. The investigation had been held by this time, Although Loftus’ attorney had been supplanted at a critical roment, when James J. Hill had been called to the witness stand, and there had been an apparent official effort to cover things up and whitewash the railroads, some startling exposures had been -made Rebating evils had been shownr- The fact was ex: posed that railroads were actively in politics; that railroad employes had been given leaves (;f ab- sence with full pay and “expenses” to fight La - Follette and other pro- gressives. Loftus went out in -advance to pledge can- didates for the 1907 legislature to an anti- Tebating law, ‘with jail sentences for violators, reciprocal demurrage, a 2-cent passenger fare, an anti-pass law and a -state primary law. - It would take too long to tell of Loftus’ efforts, of the abuse that he - Imet, of the attempts to . knife him from behind. The Equity movement had grown up in the meantime and ' Equity farmers joined with shared his ' abuse. But Loftus - Loftus in the fight. They