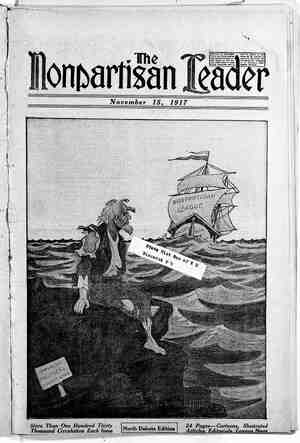

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, November 15, 1917, Page 13

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Why Women Prefer to Shop At Many Stores; A Confession and Analysis By One of Them EAR Margaret: How many stores do you visit before you buy a new coat? John came home tonight ready for an argument. That's the way he started it—by asking that question. “I've learned a_lot about women and their shopping from a salesman this afternoon,” he went on in answer. to his own question. “Women do their shopping in department] stores—in THREE department stores, to be exact. Have you ever noticed that in every town there are three department stores of the same grade, patronized by the same class of women? There may be others of a different grade catering to the tastes of other women, but each particular woman must visit her three stores before she makes any substan- tial purchases. Three seem to be the limit of her endurance.” WOMAN'S WAY ISN'T MAN’'S WAY It hadn’t occurred to me before, but when I thought it over, I admitted that it was close to the truth, When I start out to buy a coat I usually think I will go the round of all the stores in town, but by the time I have visited the third place, I have grown so tired of looking at coats, that I take one at the last place or go back to a place I have al- ready visited. “Now when I want a pair of socks,” John continued approvingly, “I go over -about two bloeks to the nearest cloth- ing store and buy them without any parley. When you want a pair of stockings, you go all the way down town and spend an hour or more going to * your three ' department stores worrying. all the time for fear you are missing a sale somewhere.” “Perfectly true,” I assented, “but you overlook one thing. I never go down town for a pair of stockings. You for- get that it is my business to purchase most of the supplies for the family. I may go down town knowing that I must take home a pair of stockings for myself, but I also know that there are about 50 other things that I have to purchase soon—each one when I find the most - favorable opportunity. I know now, for instance, that I have to have a new dishpan and some cups and saucers, shoes for the children, a ot | Ay = new rug for the hall, a good reading lamp—the . children are ruining their eyes with thag high light.” “I guess that ought to be enough for awhile,” interrupted John. “But wouldn’t it be better if you would go to one store and get your blankeéts in peace, as I 'do my socks, without hav- ing everything else on your mind and without worrying about a blanket sale that may be going on across the street.” " DO WOMEN VALUE A DOLLAR: MORE? ‘“Your;situation and mine are differ- ent,”-I 'said.. “You have to take enough money to keep you clothed respectably. It's a business proposition. It doesn’t hurt your conscience particularly if you find that you paid $2 more for your suit at Smith’s than you would have had to pay at Jones’. That is because $2 doesn’t mean to you, as it does to me, mufflers or gloves or skates for the children, or a preserving kettle for the kitchen, or curtains for the bed room.” “But it isn’t really economical in the long run,” he insisted. “You may save $2, but think of your time.” “Time,” said I, “What is time to a woman? You forget that the average housewife doesn’t earn or at least doesn’t receive wages. You remember that suit I bought last year for $12.50? I started out intending to pay $30 if I had to; but the third store I went to had this suit on sale and it was better than anything I had seen for $30. The $17.50 I saved curtained the house. It would not have done it either, if I had not happened to know about some curtain bargains—thanks to a depart- ment store system that takes me past the cutrain counter every time I go to the grocery in.the basement. Don't you see that I am actually carrying on my business of family buyer every time I go down the aisle of a department store?” : AYE THERE’S THE RUB— OR IS IT NOW? “Yes, and getting a lot of fun out of it too,” laughed John. “Out of part of it,” I corrected. “I like to go to one store and wander around with all my needs in mind, but The American Dishwasher ‘(From The Northwestern Culinary Art Journal, Minneapolis, Minn.) Nobody wants to be the dish-washer. Why? There is only one reason—it doesn’t pay. Dish-washing is just as an important work as civilized man can “conceive of—just stop and think for a minute, if dishes would not be washed—say, for one month—what kind of civilization would remain? Tn spite of the fact that a dish- washer is one of the most important of all workers, this class of labor has practically donated its. useful work to the catering industry, and out of the donation of the service of dish-wash- ers, hotel and restaurant ‘keepers, all ever the world, have become million- aires. The modern dish-washer, for the purpose of this article, may be divided fnto three classes—the young girl, the old man, and the modern dish-washing machine. The young girl is usually an immi- grant—not familiar with the English language. Having somewhat of an: jdea. of washing a dish, she believes herself to be master of a tub and in- vades the market of kitchen labor. " Here she soon finds herself at home ~—having nothing to do but wash dishes, wash floors, wasirshelves, ceil- ings, pots, pans and all other instru- ments. She makes herself generally useful and her wages are fixed by cir- cumstances, which are largely measured by the labor market, and of- her unfor- tunate competitors. Owing to the fact that vast armies of unfortunate girls from the rural dis- tricts of Europe are flooding:the labor market, the wages of a woman dish-- washer are usually just above the line of starvation. 3 The old man is usually forced into &. kitchen after everybody else has refus- ed him employment—and instead the old veteran of industry recelving. and enjoying an old age pension—the old man, whose misfortune it is to be poor, is forced to donate the rest of his life to the cleanliness of the culinary art and to the building of millionaire captains of the culinary industry. Oh, how hard it is for a bookkeeper who can not see any more, or for a bricklayer who can not climb any more, or for a painter who fell—how hard it is for these old people to again learn the profession of a dish-washer—a pearl diver. Old men have come in my kitchen and said: * show me—I must live; give me a chance,” and at the end of 12 hours per day, seven days per week, the old man said, as to wages: “I wonder how much he will give me?” And the old boss came and greeted him with a five- spot. Five dollars for 82 hours’ work —or six cents per hour. Just as in most all industrial fields, s0 in the kitchen, machinery has taken the place of all heretofore cheap hand- labor. Different from most other hand- labor, the modern dish-washing ma- chine has done all useful work; it has cleaned the dishes better than the young girl and better than the old man —by its boiling water and by its steam. No human hands are hard enough to stand boiling water. . ‘When hundreds and thousands of people eat in one hotel or restaurant —eat with the same knives, forks, spoons, plates and platters—many dif- ferent kinds of diseases are transferred by the use of dishes, but the modern dish-washing machine so sterilizes every dish that no germ can gurvive. - The modern dish-washing machine requires a gkillful operator, and he will demand fair wages and fair hours—but it will be cheaper, in the long run, and our modern culinary industry may just as well give recognition to the machine and to its operator, . “I am willing to learn—just. it's tiring to go on to the next one, I only do it because I don’t dare pot to. The thing I'd really like would be to have just one big department store in the whole city, with everything that the household needs. I'd like to know that the price I am paying is the cheapest price anybody is paying any- where in town for the same article. And I'd especially like to know that the prico doesn’t cover the cost of renting ‘many buildings for me to wear myself out visiting, more clerks than are ne- cessary, more delivery -wagons and more advertising. I can’t think of any- thing that would lighten women’s burdens more than a central purchas- ing place where they can find samples and pictures of articles that can be ordered if the goods in stock are not satisfactory.” “I don’t think the women would like Women Readers: Watch this page next week for it,”” sald my husband skeptically, “They would object to losing their per= sonal liberty of buying their goods from Mr. Mandel or Mr, Field, although they may never have seen the gentle= men.” “L can't deny that women do have some queer prejudices,” I - confessed. “I have suggested this to a good many of my friends and they aren’t all as enthusiastic as I am, by any means, But there’s plenty of time. Give women a few centuries, and they will come around to #. And I believe I'll write to Margaret now, while I'm in the mood, and get her started at it too. 1 believe in starting fires all over the country.” So here you are. Put it up to your neighbors some time and see what they think about it, : ALICE. announce- ment of a big prize contest. A chance for our women readers to make some Christmas money! " Women In This War By Publicity Department U. S. Food Administration The women in this country are view- ing statistics with a new vision. For the first time in the lives of many of them they are interpreting crop to- tals in terms of human life. Wheat and meat have come to mean to them, not ship loads and car loads, but sol- diers on the firing line, workers in field and factory, mothers and their little ones in lands devastated by war. For nearly three years the world war was mot a part of the lives of the women of this country. True, they knew that in other lands war was rushing men in the trenches. There was sympathy, deep sympathy, for those who suffered. Then suddenly the - war, thousands of miles away, stepped into the American home. It became, not a shadow or a far dis- tant mirage of distress, but something Very near. A YOUNG LEAGUER This is James McWilliams, Jr., of Edgeley, N. D., whose mother is rear- ing him to stand beside his father in :he economic fight the League is wag- ng. PAGE THIRTEEN When the war was hurled into the American home the War Mother of the land became a more conscious econo- mic factor than she had ever been be=- fore. It suddenly dawned upon her that in some way the welfare of her boy was bound up with what had be- fore been uninteresting export figures, Crop totals that had given her only a vague sort of satisfaction became a matter not only of interest but of anxiety, When the war began calling American boys to the colors, the American War Mother became the log- ical evangel of food conservation. ~ The food problem of the Allied na- tions will be solved in the American kitchen. It is a realization of that fact that has caused not only the war mothers and wives, but the grand- mothers, the aunts, the cousins, the sisters of American boys now wearing their country’s uniform to mobolize in- to a host pledged to the doctrines that since food will win this war our sup- plies must be conserved. The American War Mother is pre- pared not only to so administer the affairs of her household that the food needs of the Allied nations will be met, but she likewise is prepared to petition - the entire sisterhood of American women that they work with her in a campaign that both her rea- son and her heart tell her is vital. In every state in the nation war Mothers have become recruiting agents for the conservation army. Their pres- ence in the field has brought home a realization to all women of the human aspects of the food pledge. Stockyard figures gathered by the food administration show that 73.3 per cent of the calves slaughtered at nine large packing points in this country during the first nine months of this year were males. By furnishing plenty of meat and fat to the allies the great American hog can fight quite as formidably as his wild-boar ancestry. SUGAR CURED HAMS AND BACON ‘When the meat has been cooled and cut up rub each piece with salt and al- low it to drain over night. Then pack in a barrel with the hams and should- ers in the bottom, using the strips of bacon to fill in between or to put on top. For each 100 pounds of meat weigh out eight pounds of salt, two of brown sugar, and two ounces of salt- peter and dissolve in four gallons of water. Pour on enough of this brine to cover the meat. ‘In the summer it {s best to boil the brine. If this is done, cool it before putting on - the meat. The strips of bacon should be ‘left in four to six weeks and the hams six to eight weeks. They are then ready for smoking.