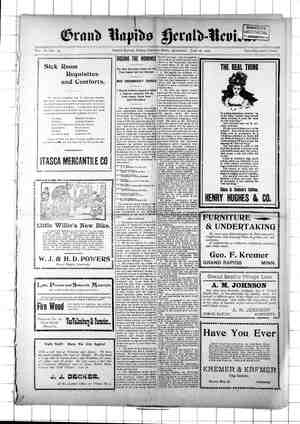

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, June 28, 1902, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

CHAPTER XVI Margaret Sees a Ghost. With a sigh of unutterable relief Enid fheard Witliams returning. Reginald Henson had not come down yet, and the rest of the servants had retirel scme time before. Willaims came up with a request as to whether he could do anytning more before he went ‘to bed. “Just or thing,” said Enid. “The good dogs have done their work weil to-night, wut they have not quite fin- fshed. Find Roilo for me, and bring him here quick. Then you can shut up the house, and I will see that Mr. Hen- son is made comfortable after his tright.” The big dog came presently, and fol- fowed Enid timidly up stairs. Appar- ently the great, black-muzzled brute tad been there before, as evidently he knew that he was doing wrong. He crawled along the corridor until h> <ame to the room where the sick gil lay, and here he followed Enid. The lamp was turned down low as Enid glanced at the bed. Then she smiled, faintly, yet Fopefully. . There was nobody in the room, The patient's bed was empty! “It works well,” Enid said. : “May it @o on as it has been started. Lie down, Rollo; iie there, good dog. if enybody comes in, tear him to pieces.” The great brute crouched down ob2 diently, thumping his tail on the floor as an indication that he understood. As ff a load had been taken from her mind, Enid crept down stairs. She had hardly reached the hall before Hensoa followed hgr. His big face was white with passion; he was trembling from head to foot with fright and pain. ‘There was a red rash on his forehead that by no -neans tended to improve his appearance, “What is the mearing of this?” he demanded. hoarsely. Enid looked at him coolly. She coult afford to do so now. All the danger ‘was past, and she felt certain that che events of che evening were unknown to him. “Y might ask you the same question,” sh esaid. “You look white and shax- en; you might have been thrown vio- fently into a heap of stones. But It is not please don't make a noise. now. Chris—” the prevarication did y as she had expected. fitting mot come a: “Chris has gone,” she said, “She passed away an nour ago.” Henson muttersd scmething that sounded like consolation. He could be polite and suave enough on occasions, ‘but not to-night. Even philanthropists are selfish at times. Moreover, his merves were badly shaken and he want- ¢d a’stimulant badly. “IT am going to bed,” ‘wear “Good-night.” She went noiselessiy up stairs, and Yienson passed into the library. He ‘was puzzled over this sudden end of Christiana Henson. He was half-in- <iined to believe ‘hat she was not ‘lead at all: he belonged to the class of men who believes nothing without proof. “Well, ne could easily ascertain that for timself. There would be quite time enough in the morning. For a long time Henson sat there *hinking and smoking, as was his usu- el custom. Like other great men, he fed his worries and troubles, and that they were mainly of his own making did not render them any lighter. So Yong as Margaret Henson was under the pressure of his thumb money was mo great object. But there were other situations where money was utterly powerless. Henson was about to give it up as a ‘bad job, for the night, at any rate. He wondered bitterly, what his admirers ‘would say if they knew everything. He ‘wondered—what was that? Somebody creeping about the house, somebody talking in soft, though dis- tinct, whispers. His quick ears de- tected that sound instantly. He slip- ged into the hall; Margaret Henson was there, with the remains of what had ence been a magnificent opera cloak @ver her shoulders, “How you startled me!” Henson said. frritably.. “Why don’t you go to bed?” Enid looked over the balustrade from @he landing, wondering, also, but she rept herself prudently hidden. The first words that she heard drove all the Glood from her heart. “JT cannot,” the feeble, moaning voice aid. “The house is full of ghosts; they haunt and follow me everywhere. And Chris is dead, and I have seen her spri- a." “So I'm told,” brutal callousness. ghost like?” “Like Chris. All pale and white, with @ frightened look on her face. And she was all dressed in white, too, with a eloak about her shoulders. And just when I was going to speak to her she Enid said, Henson said, with “What was the turned and disappeared into Enid’s bedroom. And there are other ghosts—” “One at 1 time, please,” Henson said, grimly. “So Christiana’s ghost passed fnto her sister’s bedroom? You come and sit quietly in the library, while I @nvestigate matters.” Marszaret Henson complied, in her dull, mechanical way, and Enid flew, ike a ‘lash of light, to her room. An- ther girl was there—a girl exceeding- fy like her, but looking wonderfully _ pale and drawn. “That ‘iend suspects,” Enid said. “How unfortunate it was that you should meet aunt like that. Chris, you ust go back again. Fly to your own oom ani compose yourself. Only let him see you lying white and still, there, @ud he must be satisfied.” Chris rose, wiih a shudder, “And if the wretch offers to touch me,” she moaned. “If he does—" “He will net. Me dare not. “Heaven Crimson By Fred M. White ¢ Blind help him if he tries an experiment of that kind. If he does Rollo will kill him to a certainty!” “Ah, I nad forgotten that faithful éog. Those dogs are more useful to us than a score of men. I will go by the back way,*and through my dressing reom, Oh, Enid, how glad I shall be to find myse'f outside the walls of this dreadful house!” Sh2 flew along the corridor and gained her room in safety. It was an instant’s work to throw off her cloak and compose herself rigidly under a single white sheet. But though she lay still, ner heart was beating to suf- focation 2s she heard the creak and thud of a heavy step coming up the stairs. Then the door was opened in a stealthy way, and Henson came in. He could se® .h2 outline of the white fig- ure, ard a sigh of satisfaction escaped him. A less suspicious man would have retired at once; a man less en- gaged upon his task would have seen two great, amber eyes close to the floor. “An old woman's fancy,” he mut- tered. “Still, as I am here, I will make sure that--” He stretched out his hand to touch the marble forehead, there was a snarl ‘and a gurgie, and Henson came to the fioor with a hideous crash that car- rieed him staggering beyond the door into the corridor. Rollo had the in- truder by the throat; a thousand blue and crimson stars denced before the wretched man’s eyes; he grappled with his foe with one last despairing effort, and then there came over him a vagu>, warm unconsciousness. When he came to himself he was lying in his bed, with Williarns and Enid bending ever him. “How did it happen?” Enid asked, with simulated anxiety. “I—I was walking along the corri- dor,”” Henson gasped, “going—going to bed, you see; and one of those diaboli- cal dogs must have got into the house. Befor2 I knew what I was doing, the creatur> flew at my throat and dragged me to the floor. Telephone for Walker at once. IT am dying, Williams.” He fell back once more, utterly lost to his surroundings. There was 2 great, saping, 1aw wound at the side of the throat that caused Enid to shud- der. “Do you think he is—dead, Will- iams?” she asked. “No. such luck as that,” Williams taid, with the air of a confirmed pes- simist. “I nope you locked that there bed room ‘door, and put the key in your pocket, saiss. T suppose we'd bettar send for the -loctor, unless you and me puts him out of his misery. There's one comfort, however, Mr. Henson will be in bed for che next fortnight, at any rate, so he'll be powerless to do any prying about the house. The funeral will be over long before he’s about again.” The first grey streaks of dawn were in the air as Enid stood outside the lodge gates. She was not alone, for a neat figure in grey, marvellously like her. was by her side, The figure in grey was dressed for travelling and she carried a bag in her hand. “Good-bye, dear, and good luck to you,” she said. “It is dangerous to delay.” “You have absolutely everything that you require?” Enid asked. “Everything. By the time you ar2 at breakfest I chall be in London. And once I am there the search for the secret will begin in earnest.” “You are sure that Reginald Henson suspected nothing?” “IT am perfectly certain that he was satisfied; indeed, I heard him say so. Still, if it had not been for the dogs! We are going to succeed, Enid, some- thing at my heart tells me so. See how the sun shines on vour face and in your dear eyes. Au revoir, anom2n —an omen of a glorious future.” CHAPTER XVII. The Pace Slackens, Steel lay sleepily back in the cab, not quite sure whether his cigarette was alight or not. They were well in- to the main roal again before Bell spoke, “It is pretty evident that you and I are on the same track,” he said. “T am certain that I am onthe right one,” David replied; “but, when I come to consider the thing calmly, it seems more by good luck than anything else. I came out with you to-night seeking adventure, and I am bound to/ admit that [ found it. Also, I found the laiy who intcrviewed me in the darkness, which is more to the point.” “As a matter sf fact, you ing of the kind,” said Bell, suggestion of a laugh. “Oh! Cese of the wrorg room over again. I was ready to swear to it. Whom did I speak ‘to? Whose voize was it that was so very much like hers?” is “The lady’s sister. Enid Henson was not at 218, Brunswick Square, on the night in question. Of that you may be certain. But it’s a queer business altogether. Rascality I can under- stand. I am beginning to comprehend the plot of which I am a victim. But I don’t mind admitting that up to the present I fail to comprehend why those girls evolved the grotesque scheme for getting. assistance at your hands, The whole thing savours of madness.” “IT don’t think so,” David said, thoughtfully. “The girls are romantic as well as clever. They are bound to- gether by the common ties of a com- mon enmity towards a cunning and utterly unscrupulous scoundrel. By the merest accident in the world they discovered that I-rm in a position to did noth- with the 4 ness for ty o-reasons—the first, because the family secret is a sacred one; the second, because ary disclosures would land me in great physical danger. Theretore they put their heads to- gether and evolve this scheme. Call it a mad venture if you like, but if you consider the history of your own coun’ try you can fird wilder schemes evolved and carried out by men who have had brains encugh to be trusted with the fortunes of the nation. If these girls had been less considerate for my safety——” “But,” Bell broke in, eagerly, “they failed in that respect at the very outset. You must have been spotted énstantly by the foe, who has cunningly placed you in a dangerous position, perhaps as a warning to mind your own business in future. And if those girls come for- ward to save you—and to do so‘\they must appear in public, mind you—they aré bound to give away the whole thing. Mark the beautiful cunning of it. My word, we have a foe worthy of our steel to meet.” “We? Do you mean to say that your enemy and ‘nine is;a common one?” “Certainly. When I found my foe I found yours!” “And who may he be, token?” “Reginald Henson. Mind you, I had no more idea of it than the dead when T went to Longdean Grange to-night. I went there because I had begun to sus- pect who occupied the place, and to try and ascertain how the Rembrandt en- graving got into 218 Brunswick Square. Miss Gates must have heard us talking over the matter, and that was why she went to Longdean Grange to-night.” “T hope she got home safe,” said Da- vid. ‘The cabman says he put her down opposite the Lawns.” “T hope so. Well, I found out who the foe was. And I have a pretty good idea why he played the trick upon me. He knew that Enid Henson and myself were engaged; he could see what a danger to his schemes it would be to. have a man like myself in the family. Then the second Rembrandt turned up, and there was his chance for wiping me off the slate. After that came the terri- ble family scandal between Lord Litti- mer and his wife. I cannot tell you anything of that, because I cannot speak with definite authority. But you could judge of the effect of it on Lady Littimer to-night.” “T haven’t the faintest recollection of seeing Lady Littimer to-night.” “My dear fellow, the poor lady whom you met as Mrs. Henson is really Lady Littimer. Henson is her maiden name, end those girls are her nieces. Trouble has turned the poor woman's brain. And at the bottom of the whole mystery is Reginald Henson, who is not only nephew on his mother’s side, but is also next heir but one to the Littimer title. At the present moment he is blackmail- ing the unhappy creature, and is ma- neuvering to get the whole of her large fortune into his hands. Reginald Hen- son is the man those girls want to cir- eumvyent, and for that reason they came to you. And Henson has found it out; to a certain extent, and placed you in an awkward position.” “Witness my involuntary guest and the notes, and the cigar case.’ David said. ‘But does he know what I advise one of the girls--my princess of the dark room—to do?” “I don’t fancy he does. You see, that advice was conveyed by word of mouth. The girls dared not trust themselves to cerrespondence, otherwise they might have approached you in a more prosaic manner. But ¥ confess you startled me to-night.” “What do you mean by that?” “When you sent me that note. What you virtually asked me to do was to countenance murder. When I went in- to the sick room I saw that Christiania Henson was dying. The first idea that flashed across my mind was that Res- inald Henson was getting the girl out of the way for his own purposes My dear fellow, the whole atmosphere lit- erally spoke of albumen. Walker must have been blind not to see how he was being deceived. I was about to give him my opinion, pretty plainly, when your note came up to me. And there was Enid, with her whele soul in het large eyes, pleading for my silence. If the girl died I was accessory after and before the fact. You will admit that (nat was a pretty tight place to put a doctor in.” “That's because you didn’t know the facts of the case, my dear Bell.” “Then, perhaps you'll be so good as to enlighten me,” Bell said, drily. “Certainly. That was part of my scheme. In the synopsis of the story obtained by the girls, by more or less mechanical means, the reputed death of a patient formed the crux of the tale. The idea occurred to me, after reading a charge against a medical student some time ago, in the ‘Standard.’ The man wanted to get himself out of the way; he wanted to be considered as dead, in fact. By the artful use of albu- men in certain doses he produced symp- toms of djsease which will be quite fa- miliar to you. He made himself so ill that his doctor naturally concluded that he was dying. As a matter of fact, he was dying. Had he gone on in the same way another day he would have been dead. Instead of this, he drops the dos- ing and, going to his doctor, in dis- guise, says that he is dead. He gets a certificate of his own demise, and there you are. I am not telling you fiction, but hard fact, recorded in a high-class paper. The doctor gave the certificate without viewing the body. Well. it struck me that we had here the making of a good story, and I vaguely outlined it for a certain editor. In my synopsis I suggested that it was a woman who proposed to oretend to die thus so as to lull the suspicions of a villain to sleep, and thus possess herself of certain vital documents. My synopsis falls into cer- tain hands. The owner of these hands asks me how the thing was done. I tell her. In other words, the so-called mur- der that you fmagined you had discov- ered to-night was the result of design. Walker will give his certificate, Regi- nald Henson will regard Miss Christi- ena as deadvand buried, and she will be free to act for the honor of the family." by the same cS “But they might have employed some- | body else.” i “Who would have had to be told the story of the family dishonor. So far, I fancy, I have made the ground quite clear. But the mystery of the cigar case and the notes and the poor fellow in the hospital is still as much 2 tery as ever.'We are like two. sistance, At the same time they don’t | | ist them valuable advice and as- want me to be beougey into the busi- ‘ terrible for those girls. “Of course I do. She will have a key to your trouble. It is a dreadfully rusty one and will want a deal of oiling be- fore it is used, but there it is.” “Where, my dear fellow, where?” Da- vid asked. “Why, in the Sussex county hospital, of course, The man may die, in which case everything must be sacrificed in order to saye your good name. On the other hand; he may get better, and then he will tell us all about “He might. On the other hand, he might plead ignorance. It is possible for him to suggest that the whole af- fair was merely a coincidence, so far as he was concerned.” “Yes; but he would have to explain how he burgled ycur house, and what business he had to get himself half- murdered in your conservatory. Let us get out here and walk the rest of the way to your house. Our cabby knows quite enough about us without having definite views as to your address.” The cabman was dismissed with a handsome douczur, and the two turned off the front at the corner of Eastern Terrace. Late as it was, there were a few people lounging under the hospital wall, where there was a suggestion of activity about the building unusual at that time of the night. A rough-look- ing fellow who seemed to have followed ell and Steel from the front, dropped into seat by the hospital gates and laid his hea@ back, as if utterly worn out. Just inside the ‘gates a man was smok- ing a cigarette. “Halloa Cross!” Davia cried, “you are out late te-nis' “Heavy night.” Cross responded, sleep- ily, “with half a score of accidents to finish with. Some of Palmer of Ling- field’s private »atients thrown off a coach .and brought here in the ambu- lance. Unless I am greatly mistaken, this is Hatherly Bell with you.” “The same,” Bell said, cheerfully. “I recollect you in Edinburgh. So some cf Palmer's patients have come to grief? Most of his special cases used to pass through my hands.” “I've got one here to-night who re- collects you perfectly well,” said Cross. “He's got a dislocated shoulder, but otherwise he’s doing well. Got a mania that he’s a doctor who murdered a pa- tient.” “Electric light anything to do with the story?” Bell asked, eagerly. “That's the man. Seems to have 4 wonderfully brilliant intellect if you can cnly keep him off that topic. He spot- ted you in North street, yesterday, and seemed wonderfully disappointed to find you had nothing whatever td do with this institution.” “If he is not asleep,” Bell suggested, “and you have no objection—” Cross nodded and opened the gate. Before passing inside Bell took the rolled-up Rembrandt from his breast pocket and handed it to David. “Take care of this for me,’ he whis- pered, “I'm going inside. I've dropped upon an old case that interested me very much years ago, and I'd like to see my patient again. See you in the morning, I expect. Good-night.” David nodded in reply and went his It was intensely quiet and still the weary loafer at the outside hospital seat had disappeared. There was nobody to be seen anywhere as Da- ‘Vid placed his key in the latch and openéd the door. Inside the hall light was burning, and so was the shaded electric lamp in the conservatory. The study leading to the corservatory was in darkness. The effect of the light be- hind was artistic and pleasing. It was with a sense of comfort and velief that David fastened the door be- hind him. Without putting up the light in the study David laid the Rembrandt on the table, which was immediately below the window in his work room. The night was hot; he pushed the top sash down liberally. “I must get that transparency re- moved,” he murmured, “and have the window filled with stained glass. The stuff is artistic, but it is so frankly what it assumes to be.” CHAPTER XVIII. A Common Enemy. David idly mixed himself some whisky and soda water in the dining room, where he finished his cigarette. He was tired and ready for bed now, so tired that he could hardly find energy enough to remove his boots and get into the big carpet slippers that were so old and worn. He put down the dining room lights and strolled into the study. Just for a moment he sat there, contemplat- ing with pleased, tired eyes the wilder- ness of bloom before him. ' Then he fell into a reverie, as he fre- quently did. An idea for a fascinating story crept, unbidden, into his mind. He gazed vaguely around him. Some little noise attracted his attention, the kind of a noise made by a sweep’s brushes up a chimney. David turned idly towards the open window. The top of it was but faintly illuminated by the light of the conservatory gleaming dully on the transparency over the glass. But David’s eyes were ‘keen, and he could see, distinctly, a man’s thumb, crooked downwards over the frame of \Ahe sash. Somebody had climbed up the telephone holdfasts, and was getting in the window. Steel slipped well into the shadow, but not before an idea had come to him. He removed the rolled-up Rembrandt from the table and slipped it behind a row of books in the book case. Then he looked up again at the ercoked thumb. He would recognize that thumb again anywhere. It was flat like the head of a snake, and the nail was no, larger than a pea—a thumb that had evidently been cruelly smashed at one time. The owner of the thumb might have been a common burglar, but, in the light of recent events, David was not inclined to think ‘so. At any rate he felt dis- posed to give his own theory every chance. He saw a long, fustian-covered arm follow the scarred thumb, and a hand grope all over the table. . “Curse me!” a foggy voice whispered, foarsely., ‘It ain’t here. And the bloke told me—” The yoice said no more, for David grabbed at~the arm and caught the wrist in a vice-like grip. Instantly an- shot over the window and an ae Leny of Hyon piping ‘was swung lously near 's he ‘Unfortun- ~ could see face, As he close the window and regret that his impetuosity had not been more judi- ciously restrained. “Now, what particular thing was he after?” he asked himself. “But I had better defer any further speculations on the matter until morning. After the fright he had, my friend won't come back again. And I'm just as tired as a dog.” , But there were other things the next day to occupy David's attention besides the visit of his nocturnal friend. He had found out enough the previous evening to encourage him to go further. And, surely, Miss Ruth Gates could not refuse to give him further information. He started out to call at 219 Bruns- wick Square, as soon as he deemed it excusable to do so. Miss Gates was out, the solemn butler said, but she might be found in the square gardens. David came upon her presently, with a book in her lap and herself under a shady tree. She was not reading. Her eyes were far away. As she gave David a warm greeting there was a tender bloom on her lovely face. ~~ “Oh, yes, I got home quite right)” she said. “No suspicion was aroused at all. And you?” “T had a night thrilling enough for yellow covers, as Artemus Ward says. { came here this morning to throw my self on your mercy, Miss Gates. Were I disposed to do so, I have information enough to force your hand, But I pre- fer to hear everything from your lips.’ “Did Enid tell you anything?” Ruth feltered. “Well, she allowed me to know a great deal. In the first place, I know that she had a great hand in bringing me to 218 the other night. I know that it was you who suggested the idea, and it was you who facilitated the use of Mr. Gates’ telephone. How the thing was stage- managed matters very little at present. It turns out now that your friend and Dr. Bell and myself have a common enemy.” Ruth looked up swiftly. There was something like fear in her eyes. “Have—have: you discovered the name of that enemy?” she asked. ‘Yes: I know that our foe is Mr. Reg- inald Henson.” “(To be Continued.) “MISS” OR, “MRS.” A Few Americans Say “Mistress” In- stead of “Missis—The New Woman in Germany. The German “advanced” women de- sire to follow the aerate, & their col- leagues in Paris, and to break down the barriers of custom in regard to the des- ignation of “Frau” and “Fraulein.” A meeting was held last week in Berlin, under the auspic2s of the association for promoting the Education and Stud- ies of Women, *o Giscuss the knotty question. A lady, who is a doctor of law, defended the proposed innovation, namely, that after a certain age wo- men. whether married or single, shall be entitled to call themselves Frau (Mrs.) She insisted that it was unne- vessary to ticket a woman with a de- scription of her condition—as to wheth- er she were married or a spinster, espe- cially seeing that, legilly speaking, there was nothing to prevent a “Frau- lein” calling herself “Frau.” The speaker did not like the diminutive form, “Fraulein,” for an elderly lady, deeming it disrespectful to her advanc- ing years, and cited the example of the Ee>in municipal council, which ad- dresses a school mistress on her ad- vancement to the rank of a first-class teacher (Ober-Lehrein) as “Frau.” The result of the meeting was that all those rresent were requested to exert them- selves te the utmost to get the designa- tion “Frau” accepted among their ac- quaintances as the rightful form of ad- dress when speaking to a lady of years. It will be interesting to learn what is the limit of age at which a Fraulein ceases to be a Frau, irrespective of marriage. This side of the topic was wisely dropped, doubtless for fear of divergerces of -opinion—New York Commercial~ Advertiser. Which Kind of an Aas? Dean Van Amridge is one of the very oldest of the old school and the sternest figure in the Columbia faculty. A schol- ar by profession, he was born a soldier, and the glint of his eye is in perfect ac- cord with his martial bearing, which cap and gown can not wholly conceal. The other day a student, in the height of freshman idiocy, burst into the dean’s office with some request or other on the end of his tongue. The dean was deep in a work on philosophy, but the verdant youth, without removing his hat from his head, his cigarette from his lips, or even his hands from his pockets, kicked the ponderous door shut with a bang that rattled the windows very much and the dean some. The young man’s name was Thomas. “Sir!” cried the.dean, “do you know you're an ass?” “Yes, sir—Thom-as,” youth, suavely. “No, sir—jack-ass!” roared the dean, and he turned again to his books.—New York Times. Feanondey the ‘Worse and Worse. A lawy2r, with a penchant for bill- iards, had occasion recently to visit a small tow. While there, seeking to pass his time, he found in his hotel a new and excellent billiard table. Upon inquiring if there was anybody about who played, the landlord referred him to one,of the natives, who may be called John‘ Jones. They played several games, but the | result was always against the lawyer. | He couldn't win. “Mr. Jones,” he remarked, quite a reputation at home. They con- sider me a good billiard player. But I am far benind you. May I inquire how long you have played?” “Oh, not long,” replied the native, “gnd I don’t want to hurt your feelin's, but you’re the fust feller I ever beat!"— Cassell’s Journal. “T have Easily Read. “Yes; she can read her husband like a book.” “Is that little, sawed-off fellow her husband?” “Yes.” . } “Huh! I should think she’d read him} | Ike a paragraph.”—Philadelphia Press. “Yes; Bi ins has completed his new airship, an¢ or » will name it ‘Truth.’” 1s of Noted recs ee it article on thi ‘ania of Authors,” in the Revue vee catte of Paris, we are toli that Darwin always practiced on his old fiddle before writ- ing. Chateaubriand, while dictating to his secretary, was in the habit of walk- ing in his bare feet; Schiller and Goethe could not write unless their feet were on ice; Lord Derby; always filled his mouth with brandy cherries; Fenimore Cooper used to chew gum drops; By- ron filled his pockets with truffles; The- ophile Gautier bu:ned incense; Pierre Loti gets intoxicated with perfumes.— Exchange. What We Owe to Cockfighting. The now disreputable amusement of cockfighting (which was once respecta- ble enough to divide with scholarship and archery the attention of Roger As- cham) has provided the language with “crestfallen,” “in high feather,” and Shakespenre’s ‘‘overcrow” (cf. to crow over.) “To show the white feather” is from the same source, since white feathers in a gamecock’s tail are a sign of impure breeding. Often the origin of such words or phrases has been quite forgotten; but, when traced, show their true character at once. “Fair play” is still recognized as a figure from gam- bling; but “foul play,” now specialized to “murder,” is hardly felt as a meta- phor at all.—Open Court. The Secret of Health in Old Age. Shepherd, Ill., June 234.—Sarah E. Rowe of this place is now 72 years of age, and just at the present time is en- jcying much better health than she has for over 20 years. Her explanation of this is as follows: “For many years past I have been troubled constantly with severe Kidney Trouble, my urine would scald and burn when passing, and I was very miser- able. “I am 72 years of age, and never ex- pected to get anything to cure me, but I heard of Dodd’s Kidney Pills, and thought it would do me no harm to try them. “I am very glad I did so, for they cured me of the Kidney Disease and stopped the scalding sensations when Passing the urine. “I feel better now than I have for twenty years.’ The Typical Tramp. There is no such thing as a typical tramp incarnate. He has his existence only in the comic weekly and newspa- per supplement. The average hobo, un- der a different environment, would be the average man; under his existing envivrcnment he approximates thereto, though that environment tends strong- ly to multiplication of types rather than to uniformity. Consider that your hobo travels many thousand miles in a year, visiting places of interest and large cities besides—in a majority of eases doing many different kinds of work. And even the yegg man, the un- mitigated beggar of the road, and his telltale visage and manner, is widely varied in general appearance, habits of thought and business methods.— Frank Leslie's Monthly. THE TORTURE OF PILES relieved promptly, and permanently cured by Cole’s Carbolisalve. Guarantes goes with each box. Get the genuine. At drug- gists, 25c and 50c. Stockton a “Coupe.” In the early days of his journalistic the late Frank R. Stockton was stand- ing with a group of newspaper men, listening to the eloquence of one of their number, who, on the strength of some small authority,, was giving his views on “higher journalism,” in a pompous and bombastic manner. At the close of a sonorous period he paused for breath, when Mr, Stockton. speaking for the first time ventured, mildly, to disagree with the opinion ex- pressed. “Who are you, to dispute me?” blazed the great man. ‘Why, you are only a literary hack!” “Not even that,” responded Stockton, meekly. “I’m onl y a_ coupe.”—New York Times. He Made No Mistake. “TI sho’ did see Marse Tom's ghost las’ night,” said the old family servant. “Are you sure of that?” he was asked. "Yes, suh—sho’ ez you stan’in’ dar! I eculdn’t make no mistakes, kaze he gene straight ter de sideboard, whar de ol’ jimmyjohn stay at, en de fust word he say wuz: ‘Dam ef dat nigger ain’t been drinkin’ my licker ag’in!’ ”—Atlan- ta Constitution. Hall’s Catarrh Cure Is a constitutional cure. Price, 75 cents Nine times out of a possible ten a proud spirit in a woman is mistaken for a sour disposition. Most men wish their wives wouldn't tell them everythirg—so often. H.C.NEAL Manufacturer of AWNINGS 4"30'Sizes FLAGS Canvas Covers ot All Kinds. Boat Fittings. Tents for Rent. ~ East Third Street, - St.Paul, Minn. iDeléghokeaean. OU _CAN DO IT TOO Over 2,000,000 people are now buy- ing goods from us at wholesale prices—saving 15 to 40 percent on every- thing they use. You can do it too. “Why not ask us to send you our 1,000- Page catalogue *it tells the story. Send _ 18 cents for it today. *. ’ } ee eee ee ne