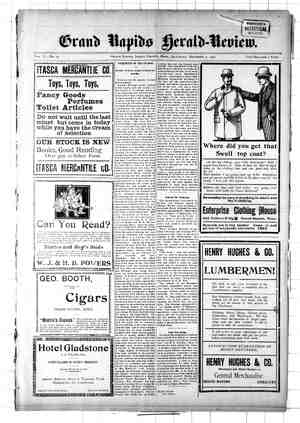

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, December 7, 1901, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

'9.0000-000000000000000000000 TTS CTC CST & Rickerby’s Folly Coxnenrererrerrerervery § 00-0-0-0-0-0.0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0:0-0-0 0000-000 CHAPTER III. (Continued.) His meditations were interrupted by @ weice close beside him; turning, some- what abruptly—-fer it was disconcerting to discover anyone in that quiet spot end so unexpectedly near to him—he saw 2 tall, lanky youth, with a curious, self-satisfied smile upon his face, and with his hands thrust under the skirts of a very Ieng and very dingy New- market coat. A hat, of a sporting shape, was stuck on the back of his smal, round head, ard there dropped from one corner of his meuth a cigar- ette, from which a little spiral of smoke went up inte one eye, causing him to wink witheat meaning it. He might fave been, from his appearance, any- where from seventeen to twenty, was evidently one of those person: direct product of a cemocratic age— whe would have accosicd a prince of the blood royal as readily as a gutter urchin. He shuftled a little nearer to Giteert Rickerby, and turned the eye {nta which the smoke was drifting to- wards the house on the opposite side of the read- “There's things a-g on over there, £ give you my word,” he mutiered, hearsely. “Are you cn the same lay as Gilbert drew back from him, frown- | fng a. little. “What do you mean? “Ob, dont be uprpish. standin” about ‘ere t a-watehin® that crib. toskin® for the ghost?” “Ghast! What ghost?” asked Gil- bert, interested, in spite of himself. “I knew nothing about the house; I’ve enly heard about the man who belonged there, and whe is dead. Has he left his ghost behind?” He asked the ques- tion somewhat bitterly, thinking of his own unkappy fate. “Give if up. They've talked about it for years, I understand--about the @hbost that’s in the side of the house they don’t use. None of the servants will go near that side, for fear of it. fhey say the old bloke’s wife died there, and ‘as been ‘aunting it ever @ince. P’raps the dead chap'l! join ‘er aow.” “Well—and what have you to do with 2” asked Gilbert Rickerby, somewhat resentfully. “I suppose they can look after their own ghost, can’t they?” “P'raps they can—and p’riaps they he 1. I've seen you hour or more, P'raps you're ¢an't,” responded the youth. “That's where my business comes in. Let me ask you this ere: “‘W’y ‘ave they been talkin’ so bold about the ghost, this fast day or two-—w’y ’ave they been tellin’ everybody about ’ow it walks at night—an’ what it does—eh? I tell you there’s summink %e’ind it—or my name ain't "Ubbard!” “is that your name?” asked Gilbert. “Ome of “em,” replied the other. ‘An’ Fm going to keep my eye on that “euse—ghosts er no ghosts. I know a bit—i do; an’ Pil know a bit more, be- fore I've done.” Before Gilbert Rickerby could reply, the youth in the Newmarket coat swung on his heel and went oft, whi Urg. Gilbert looked after him, with certain new thoughts beginning to take @hape in his mind. “Perhaps the dead chap will join fer!" Why not? Heaver knows, if the ehest ef my poor, unhappy mother haunts the place where she wept her unhappy life away, there should be mething to fear from her. Why, in a sense, I am a ghost myself; so far as the world knows, the body of me lies under the turf; Gilbert Rickerby is a mame, to be soon fergotten. Yet, before the ie quite forgotten, there is a thing he must do. ‘Perhaps the dead chap wili feir her! Yes—the dead chap shall! ‘That side of the house is deserted—and & know a way into it—a way I have not wsed for years. Gilbert Rickerby is dead; but the ghost of him goes back to his father’s house to-night! Four years before, when he had been tarred out of the place, for the last @ime, by his father, he had carried away with him, quite unconsciously, a very practical memento of his meetings with his girlish sweetheart. The me- mento was no other than the key of a Bittle gate, long disused, which opened fnte a small alley at the back of the house. The girl had given it to him in erder that he might creep in at night, to whisper his vows to her, without the chance of discovery; and he had been surprised at finding it in his pocket, months afterwards, when he was miles away from London. But, remembering the service it had rendered him, he kept it, merely for sentimental reasons, and to remind him—if any reminder were necessary—of those happy, stolen meetings. It was in his waistcoat pock- @t maw; he took it out and looked at it with a smile. “As a ghost, Gilbert Rickerby, you @re a fraud,” he said. “All the decent ghosts of which I hav+ ever read found tt quite easy to slip through cracks or key-holes, or slide down chimney-pots; you must needs go in like a thing of fiesh and blood. Well, never mind; you shall make up for it afterwards. Now, te begin—it’s weil you have strong merves, Gilbert Rickerby, for I suspect yau'li want them.” * He waited until he was certain that me ane was in sight, and then slipped found to that narrow little alley he re- membered se well. The bolt of the lock Rad not been shot since the time—four years ago—when ne crept in to see his sweetheart; it moved uneasily and compiainingly. But still it moved; and tm a moment he had glided through and had closed and locked the door behind him, and stood fn the darkness of the garden, looking up at the grim old place that had teen his mother’s pris- on. About tis feet clung the dank and gotten leaves and weeds that had been allowed to accumulate there for years; the wind blew =bout him drearily, like the sighs and whicperings of ghostly things. Shuddering a little and tread- ng cautiously, 1¢ made his way—still Sweerying tn the shadow of that deserted side of the double house—towards a door at the back. The memory of old, boyish days was strong upon him, and he had no difticulty in finding his way about in the darkness. To his surprise, the door was merely latched; it became evident, in a moment, that the place had been so long uninhabited and left to ruin and decay, vhat fastenings were not thought of. Gaining confidence, he slowly pushed open the door, and found himself in deeper darkness than before and in a stone-flagged passage. Here he S on certain ground— knew every inch of it. Cautiously feel- ing his way along tle wall, he came, at the end of the passage, to a door, “I ought to know this room,” he thought. “I’ve crept down here many and many a time to get on the soft side of old Jemima for goodies. What's be- come of Jemima, I wonder? Dead long ago, I expect. However, there’s a stair in here leading to the upper rooms. He turned the handle and stepped in- to the room, and stepped, in a moment, into a blaze of light. There was no time to retract; in fact, he was too much amazed to know what to do. For there. facing him, and standing, look- ing steadily at him, was a figure that might have sprung straight out of the buried past. It was an old woman—one of those old women who seem never, by any y, to have been young; who h bent shoulders and feeble through one’s childhood. and steps seem not a day older when one’s hair is gray. This old woman had a lined old face, with a yellowish tinge in it, and sps of her gray hair had strayed out of place and were tumbling into her eyes. Dull eyes they were, as though they had locked on the world for a long time and had found nothing particular- ly interesting. She turned, without the least haste or trenidation, and picked up a lighted candle from the table, brought it quite steadily close to the face of the man; turned, and set it down again. “Master Gilbert,” she said, entirely without emotion, “you’ve come ’ome.” Now, if the old woman, on seeing him, had screamed or fainted, or done any other of the thing swe are gener- ally led to suppose a woman does under the influence of fright or surprise, Gil- bert Rickerby would probably have known what to do, But to be greeted in this callous fashion, as though he kad merely returned to the house after a casual] evening stroll, when, as a mat- ter of fact, he had not seen the old creature for years, was more than startling; it was terrifying. But you—you didn’t expect to see 2” he began, feebly. “[ don’t never expect to see any- body,” she muttered, with a short ; laugh—‘but they comes, all the same. I only believes what I sees—and not much of that. And—oh, dear me!—the lies people do tell!” She said it all in the sarne monotonous tone, and quite without resentment, almost as though it were a thing to be expected and made the best of. “What lies?” he asked. ‘W’y—they said you was dead: they ‘av bin a-layin’ theirselves out on mournin’ for you. Come ’ome, that there Leathwood did, with a pack 0’ lies about buryin’ you. Shouldn’t won- der if they don’t clay a tombstone on you, with a burn an’ a trowel.” “But, look here, Jemima—I am dead,” said Gilbert, earnestly. ‘“‘There must be no mistake about that; Iam as dead as the deadest door nail.” “Oh—I don’t mind,” she replied, with a shrug; ‘“’ave it yer own way—please yerself an’ you'll please me. It seems to me, in this world, it don't matter much whether a person’s dead or alive; they’re pretty much of a muchness. Please yerself.” “But I want you, Jemima, to say it in the old, childish way, I'm going to play dead. I’m going—” “Play away,” she broke in. “You was always a queer boy—and God knows you ‘ad enough to make you queer, If it pleases you to come back ‘ere and say you're dead—then dead it is. I never was one to spoil sport.” “But I want you, Jeminma, to say nothing ,about me, to let them believe that IT am dead; no matter what you're asked, you know nothing about me.” “I shan’t say anything,” she replied. “I ain’t worth mentioning.” He knew from old experience that he could trust her; knew that whatever duties she had to perform in that in- habited part of Rickerby’s Folly, she would say nothing about the strange tenant of the part which had been giv- en over to decay. So far as she was concerned, he might wander about the old house as much as he liked, and she would take his presence there quite as a matter of course. She went away presently; he heard her shuffling along among the dead leaves towards the other house. He was alone in the place in which he had been born, and not twenty yards away, the man who had falsely buried anoth- er in his stead, wore black clothing in pretended sorrow for him. It was a grim thought, and made him shiver a little. He took the candle and went up stairs. The rooms were damp and mouldy-smelling, from having long been snut up; dust was thick every- where, He opened the door of one room —whicn had been his when a boy, and set down the cand‘e on the dressing table. “A queer home-coming,” he muttered. “1 suppose I can shake the dust off the bed a bit, and sleep in my clothes on top of it. Well, I've slept in worse Places before now.” There was a cupboard beside the bed —a tall, gaunt old cupboard, fitted into a recess into the wall. He remembered hew it used to be a place of dread to him in his childhood; the fastening of it had been too high for his hands to reach then, and it had always seemed ag though somethinz uncanny must be m { | | | hidden behind its door. brance of his uld fears, and a little con- tempt in his mird for that trembling boy of long ago, hg picked up the can- die and went to the cupboard and laid With a remem- his han@ upen the latch. The door yielded at once and flew epen. Even as it flew open, something big and heavy lurched forward out of it and fell upon him and upon the candle, knocking out the light and almost throwing him to the floor. He heard a thud as the something, whatever it fell at his feet. He was in total darkness, and, for some strange reason, was trembling vi- olently. For, curiously enough, as that which fell out of the cupboard fell against him, in the moment before the light was extinguished, he thought he had a glimpse of a face—only a glimpse of less than the fraction of a second. Trembling still, but deriding bis fears, he took out a match-box and, with shaking hands, essayed to get a light. The first match flared and spluttered —threw a little bluish haze round—and went out; but it had been enough to let him see that something long and dark, like a body, was at his feet. He] struck another match; and this time it flared up brightly; he lowered it, and himself, too, towards what lay at his feet. Good heavens—it was a body! He tcok the light slowly. along the length of it until he came to the face, bent nearer to it, and then cried out wildly and dropped the match. The face was that of a dead man, horribly distorted; and it was the face of the messenger he had sent into Rickerby’s Folly—James Holden! CHAPTER Iv. Little Miss Innocent. Nugent Leathwood was haunted in a double sense. For the moment he knew that he was safe; he had public- ly claimed a man as Gilbert Rickerby, and had buried him under that name; beyond tMat, the real Gilbert Rickerby was hidden away in a cupboard, in that ghostly house into which no one ever went. So far, so good; but then the haunting hegan. In the first place, it was absolutely impossible for him to know what rav- ings the man Probyn, who had died in the hospital, had been guilty of before his death; what words he might have let slip which wouid give the whole clue to the murder. If only he could know what had been said—who had been with the man when he died—what they had found upon him. With the cowardice of the man whose hands are bloo¢stained he felt that even these surgeons and nurses were capable of lying to him, ti entrap\him, if possible. Again, at any time, some man might spring upon him from nowhere, to de- mand what had become of Miles Pro- byn. Oh, it had been a great and splen- did scheme, to seize upon that one frail chance ,of a delirious man dying with that name upon his lips—to declare that that man was the one he had mur- dered! That was a stroke of genius; the world was at liberty to look upon the tombstone of Gilbert Rickerby, without knowing what ghastly fraud lay beneath it. If only Miles Probyn was of little enough importance not to he sought after, Nugent Leathwood was safe. But, on the other hand, that horrible thing shut up in the cupboard of the empty house haunted him. At night, when he went out into the old garden and glanced up at the dark windows, he could have sworn he saw a horrible, distorted face passing to and fro be- hind the glass; over and over again at night he woke up, with a cry on his lips, from a dream he had had of strug- gling over the floor with someone and choking the life out of him. A dozen times he made up his mind to flee the place and have done with it; as many times he knew that he dared not, be- cause of the thing that was hidden there. Moreover, .there was another reason why he should remain at Rickerby’s Folly; and the reason was, perhaps, pretty well explained in a conversation he had with old Cornelius, on the after- noon of the day on which Gilbert Rick- erby so mysteriously took up his resi- dence in the deserted house. Nugent sat alone in a room adjoining that in which he had been on that first night when the messenger came to him; he sat alone befor2 the fire, staring mood- ily into it and chewing the stump of a burnt-out cigar. At the very moment when he was least prepared for any in- terruption old Cornelius stood beside him ané laid a hand upon his shoulder. Nugent sprang to his feet and struck at him blindly, overturning the chair on which he had been sitting; saw who it was, and tried to laugh. “You doddering idiot! Why do you creep about like a ghost in that fash- ion, scaring people out of their wits? Shout, or dance, or sing, when you en- ter a room; the place is quite enough like a vault without any of your grave- yard antics. What do you want?” Cornelius—not in the least disturbed by the other’s onslaught—smiled grim- ly, and jerked his head in the direction of the second house. “You ‘aven’t got no fear it'll walk, ’ave you?” he asked. “Hush!” cried the other, glancing over his shoulder. “Haven't I told you I'll have no more said about it? Isn't it enough that the thing should be with me, night and day, without your drag- ging it out? Now, come, Cornelius, we have got to face this thing—to fight it out as best we can. The man is dead— doubly dead.. That idiot, Probyn, stuck himself in the way and got what he de- served; he’s buried, under a more re- spectable-name than he ever bore in his life. The real man we've got to dispose of.” “Yes, that’s the next thing to be done,” said Cornelius, scratching his ¢hin and glancing out of one eye at his master. ‘You see, you can’t go a-leav- in’ dead folk stuck about the ‘ouse: you never know what may ‘appen. Then, there's the gel.” “Yes,” replied Nugent, slowly, “I’m thinking of the girl. The girl is every- thing—the reason for this man’s death —the reason for whatever danger there may be in it for us. Now, let us look at the thing fairly and calmly. In the first place, who is to suspect us?” “That’s the second time,” said Cor- nelius, with much gravity, “that you’ve spoke of ‘us.’ I don’t like it. Try a change.” Nugent Leathwood twisted round in his chair and looked at the old man strangely. “Well, what’s the game now, Corne- lius?” he asked. “Do you back down on me? Come—out with ft; I’m net the man to stand any shuffling.” ‘Now you're a-losin’ your temper,” retorted Cornelius, nodding his head slowly and pointing at him. “Don’t do it; it ain't wise.. What I says I mean; I ain't goin’ to take nothin’ on my shoulders as don't belong to me. So, drop that little word ‘us.’ It ain't ap- propriate, More than that’’—he spoke with sudden flerceness—‘‘say it again, an’ I've done with yer! “Come, Cornelius, you don’t mean that, I’ mesure,” said the other, in a changed voice. “You wouldn’t go back on one who is prepared to do as much for you as I am—would you? Come, you shall be rich—as rich as T am; you shall never want for anything. Don’t be a fool, Cornelius; you and I have too much at stake to quarrel New let us— I beg your pardon, I'm sure—let me dis- cuss the matteh clearly.” Cornelius, somewhat mollified, sat down and prepared to listen; Leath- wood, with an evil glance at him, pro- ceeded to state what he wanted and what he intended. “In the first place, Cornelius, you know that this girl comes here to- night; in order to allay any possible suspicion she may have, you will meet her at the station—an old family ser- vant, and all that kind of thing. I have managed the matter very carefully; I have told her in writing, that she is to meet Gilbert Rickerby at this hot'se to- night; that I have arranged that they shall both be here at the same’ time. Well, they will both be here at the same time’’—he laughed and glanced at his companion—“but I’m afraid they won't meet—eh?” “I don’t think they will,” replied Cor- nelius, with a chuckle. “After that, when the girl arrives, I shall, of course, explain the death of her lover; his burial; can show her his grave, if she likes. Remember, Cor- nelius, she hasn’t a friend in the world except myself; bear that well in mind. She comes here alone; being of age, she can do as she likes. Do you follow me, Cornelius?"’—he sprang up from his air and brought his hand down heav- ily on the old man’s shoulder—‘the thing is done! Gilbert Rickerby is gone; everything that should have been his--everything he was coming home to claim—is mine; fortune—girl ~~everything!”” “The gel—as a gel—don’t appeal to me,” said Cornelius, somewhat scorn- fully. “I've always found as ‘ow gels is apt to get in the way. I on’y made one mistake in that way myself—and it’s lasted me a lifetime.” Nugent Lethwood turned upon him quickly. “By the way—that reminds me,” he said. “That wife of yours— Jemima—what about her?” “Well—what about ‘er?” demanded Cornelius, resontfully. “Ain't it enough for a man to ’ave the thoughts of such a wife, without bein’ reminded of it? What about ’er?” “I mean—is she safe? Remember, we can take no risks; that old woman is about the house all day long—all night long, for all that I know. What if she should—” ; Cornelius waved his hand impatient- ly. “There ain’t no fear,’’ he said. “That there woman is of such a stony nature that it’s my belief that, if she saw you a-cuttin’ up a person into inches, she’d git a basket and collect the bits. Nothin’ moves 'er—leastways, I was never able to. She ’asn’t no soul, ’asn’t Jemima.” “Lucky for her!” muttered Nugent. “By the way, it was strange you should come together again, after so many years. Quite accidental?” “Yes, quite accidental,” replied Cor- nelius, thoughtfully. ‘I married Jemi- ma when I was quite a young man— some said ’andsome; she was reported to ’ave a bit laid by. She must ‘ave laid it by pretty carefully, for I never saw it. Anyways, she ‘ad a son, an’ soon after that I left ’er.’ “And came back again?” “Yes. She’d been in service ’ere with Mrs. Rickerby. I left ’er ‘ere; I came back twenty years after—an ‘ere she was still. She told me the boy was gone; what she meant by that I never asked. I thought she might ‘ave an- other bit put by—but I ’aven’t found it yet.” “Well, never’ mind about that,” said Nugent, quickly. “You won't need it; I'll swear you won't need it. Only I want to be sure that the old woman is safe.” “Make your mind easy,” replied the other. “What few wits she ever ‘ad I took good care to worry out of 'er long ago. Now, I'll go an’ look after this gel. What's she like to look at?” “Very pretty, very slight, and very dark; you’ll know her easily enough— there’s not likely to be more than ene girl waiting about Paddington, looking for scmeone to meet her. I'd go my- self, but that I want to allay any sus- picions she might have. Besides, you look so infernally respectable, Corne- lius, when you haven't got that grin on your face, that she’s sure to believe in you. Tell her, when you meet her, that I’m here, entertaining her lover. Don’t forget that, Cornelius; entertaining—— ha! ha!—her lover!” : Cornelius, muttering choice opinions about “gels” in general, and this one in particular, set off upon his errand; and Nugent Leathwood was once more left alone. But to be alone in that place seemed unbearable. He went out into the garden and walked there restlessly under the stars. “It has been cleverly, done,” he mut- tered, as he walked dmong the dead leaves and stirred them into heaps with his feet; “cleverly done, indeed. I made it all so public—advertised so freely, was so ready to give the fullest information te every pressman who came upon the scene—that I’m the last man in the world they would suspect. And to-night little Miss Innocent walks into the spider’s web, with her eyes open, to look for her lover. Well, she'll find one, but not' the lover she antici- pates.” Still walking up and down, he glanced up at the dark house into which he had gone so recently with Cornelius, when they bore between them something at which he dared not look. Despite the fact that everything appeared to be go- ing so smoothly, he shuddered a little and glanced about him uneasily in the darkness. “That was a good idea, too—about the ghosts. I’ve put it about pretty broad- ly, among ignorant tradesmen'’s boys and others, that the old place is haunt- ed; that lights are seen at night and noises heard from there. I don’t think anyone wili venture near in a hurry. ‘Well, if any ghosts ever walk the earth, I should think there ought to be one stirring in that house just now.” In his restless wanderings he had got around to the farther side of the de- serted house; as he walked along un- der the shadow of the high wall of the garden, he glanced up at the windows. As he did so, he saw, with terror and amazement, that the window of that room in which he had so hurriedly hid- den the body of the dead man, glowed faintly with light from within. Even while he stood gazing up at it, there passed across the blind—hideously large, and seeming to loom threaten- ingly over him—the shadow of a man. At first, while he leaned against the wall, and caught at its rough bricks as if for support, he saw only the head and shoulders; but, gradually these rose and widened on the blind, until he saw the legs clearly; then the light went out; and there might have been no house at all there, for all he could see of it in the darkness. “It—it isn’t true—it can’t be!’ he whispered to himself, while he stood trembling in every limb, propped up against the wall. “Ghosts don’t walk in these days; men can’t come out of the shades— Who's there?” Someone was moving in the garden, coming towards him. Going forward, fearfully, he saw, after a moment, that it was the old woman, Jemima, totter- ing along and muttering to herself. Glad of any contact with human things at that moment, he sprang forward and caught her by the shoulders. “Jemima, who is in that room? An- swer me, quickly, or I shall go mad. Who is in that room?” He pointed, with shaking hand, towards the win- dow where he had seen the shadow. (To Be Continued.) WAS SAVED BY HIS WIT. But He Cut Out the Trick From the Bill Afterwards. “It was a pretty close shave, and nothing but my presence of mind is re- sponsible for my being able to tell of it now aid the old magician. “Sev- eral years ago I made a tour of the West. One night, while showing in 2 small town, I made use of what I con- sider my greatest and most inystifying trick—that of catching in my teeth a bullet fired from a gun. The trick—for it is nothing but a trick—is of itself very danger2us, and it is for that rea- son that I seldom ever attempt it. But that night my audience was so enthu- siastic thet I :esolved to give it. When I called for the man to step forward to fire the gun, the audience took it for granted that the local bad man—a dead shot, by the way—should be the man, and he came swaggering up to the platform. Well, the trick was a com- plete success, and I was well repaid for the danger that I had run by seeing the look of amaze cn the bad man’s face when I showed him the marked bullet between my teeth. After the performance was over I went to my ho- tel, and, while enjoying a good-night cigar before going to bei, the office was suddenly invaded by a mob of excited men, headed by the ‘bad man. “Here, pard,’ said he, seizing hold ef me and shoving.me up against the wall. ‘Bill, here, wasn’t at the show, and he says he don’t believe youcan catch a bullet with your teeth, and I’ve bet him $10 that you kin.’ Then, before I could find my tongue, he backed off about fifteen paces and drew a gun. ‘Now, git ready, pard!’ shouted the bad man, as he crew a bead on me. Right here was where I did the most rapid thinking of my Ife. Hastily passing my hand over my mouth, I extracted my false teeth, and then pleaded that I should have to go to my room before I could do the trick. I left, ostensibly to get the teeth, but, really to catch a train out of town. I cut that trick for the balance of the trip.”"—London Mail. A Wrinkle in Apple Packing. “There is a knack in doing every- thing,” is an old saying, and the truth- fulness of it was brought to mind re- cently by a gang of men engaged in wrapping and packing apples Each had a full box of apples, a pile of thin pa- per cut into wrappers and an empty box. An apple was taken from the full box, a wrapper put around it, and it was put in the other box. It is not an easy thing to pick up a wrapper of thin paper without missing one occasionally, and in doing so the men adopted dif- ferent schemes. A new hand wet his thumb on his tongue for every wrap- per. One ‘who had been lohger in the business, and found it was unwhole- seme to be wetting his thumb on his tongue, had a silce of lemon beside his pile of wrappers, and moistened his thumb in the lemon before picking up the wrapper. The scheme worked well, but he did not know whether the acid of the lemon would make his thumb sore or not. A third man had a thin rubber thumbstali on his thumb, and could pick up wrappers all day long and never make a miss. He was an old hand at the business.—Morning Orego- nian. Forgotten Directions. As the steamer pitched and rolled in the waves the traveler heard, through the thin partition, a wailing voice in the next state room exclaim: “Oh, mamma, it's coming again, worse than ever!” Then he heard a sleepy voice in re- ply: “Marie, why don’t you follow the di- rections you told me abcut before we came on board?” “Because I've forgotten whether I ought to breathe as the vessel rises, and let the oreath go out as it moves downward, or whether it ought to be the other way, and, oh! oh! oh! I wish I was dead!""—Epworth Herald. Nansen’s Plea for Polar Discovery. In an interesting article in Frank Les- lie’s Popular Monthly for November the great explorer closes with this appeal: “In our age of avarice and greed, when the nations stand armed to the the teeth to fight for power and pelf, and one begins to have doubts as to the moral progress of humanity, it seems like a ray of light to see men setting sail for higher goals. Let us, then, wish them Godspeed on their several quests in Browning's words: Gone Before. “TI confess to a peculiar and even pa- thetic interest in this old college foot ball ground,” said the middle-aged man, who was revisiting h's alma ma- ter after the lapse of many years. “It seems a part of yourself, I pre- sume?” observed the other man. “Yes; that ‘s what invests it with the peculiar interest,’ he rejoined. “When I played my laat game on these grounds I left a finger joint and part of an ear somewhere about here,”—Chi- cago Tribune.’ BOUNDARY LINES. NATIONAL FRONTIERS ARE NOT ALWAYS DELIMITED. The Alaska-Canada Line, for a Great Part of Its Length, Can Only be Guessed at Asserts This Writer— Possible Controversy. Dr. Mill, the British geographer, re- cently called attention to the fact that Great Britain has still one important colonial boundary entirely undelimit- ed in a little known region, where gold fields will probaby be found or reported before long, and where there- fore, a serious international question may suddenly arise. He says it would cost a comparative trifle to survey the region in question and to lay down the boundary line before the gold fields are touched, so that no interna- tional trouble about it could ever arise. Dr. Mill did not mention the particular boundary to which he re- ferred, but there is little doubt that he was thinking of one of two lines. The boundary between Alaska and Canada along the 141st meridian has not yet been delimited except along its southern part. The exact frontier between the two countries, for several hundred miles, can only be guessed at until it has been scientifically deter- mined and marked at frequent inter- vals by boundary monuments, such as the United States and Mexico have erected along their entire frontier be- tween the place where the Rio Grande ceases to be the boundary and the Pa- cific ocean. It is not at all unlikely that gold may be discovered in the neighborhood of this boundary at any time. When this occurs it will be a source of inconvenience to miners if they do not know definitely whether heir claims ave in the United States or Canada and history would only re- peat itself if the misunderstanding arising from this lack of: knowledge should result in some international unpleasantness. It is possible, how- ever, that Dr. Mill refers to the bound- ary line between German southwest Africa and the British possessions. It is known that the German colony ts rich in minerals. New discoveries are frequently made, and no one knows yet how extensive the profitable mining region may prove to be. The larger part of the boundary extends along the meridian of 20 degrees east longitude, but this line has not been defimited. It is certainly better to determine by an exact survey the position of sueh’ boundary lines before the value of the land near them may give rise to dis- putes and result perhaps in blood- shed. We had an illustration in June ast of the embarrassment which is .pt to result from ignorance of the lo- vation of a boundary line. It will be ‘emembered that some of our miners have invested considerable money in claims a little to the north of Mount Baker, which is in the state of Wash- ington, before it was discovered by a survey that our citizens had opened their claims under the provisions of our mining laws in territory that was clearly over the border in Canada. The result was most energetic claim-jump- ing on the part of Canadians and therr was some trouble and bad feeling be- fore the matter was finally adjusted. {t was, of course, unfortunate that the doundary question between our ceun- ‘ry and Canada in the neighborhood of Skagway had not been settled be- fore the interests of the citizens of both countries were determined to hold on tenaciously to territory which each declared was in his own country. This boundary question is still unde- termined, though a modus vivendi has been arranged. It sometimes costs a great deal of money to postpone the settlement of boundary questions until claims have been pegged out on debatable land. The historic controversy between Venezue- la and British Guiana should be a warning to all nations that danger lurks along the line of unsettled boundaries.—New York Sun. Saved by His Gallantry. Good maners have always been ree- ognized as a valuable help to com- tortable living, but a story told by An- drew Lang, who declares that he had it from a d€scendant of the gentleman in the case shows that they may also afford, on occasion, the only way of living at all. Roderick Macculloch, a Highland giant, no less than six feet four inches in height, had been ar- rested for treason and was on his way to the Tower, when the procession waa temporarily blockaded. A lady, look- ing out of a window, called to the vie- tim: ‘You tall rebel! You will soon be shorter by a head.” Roderick took off his hat and made a profound obeis- ance. “Does that give you pleasure, madam?” he asked. “It certainly does,” replied the lady. » “Then, madam,” re- torted Roderick, with another flourish, “I do not die in vain.”, The answer so captivated the sensibilities of the lady that she made an immediate appeal for clemency to the reigning monarch, George II., and Mr. Lang declares that he saw the rebel’s pardon, beautifully engrossed within a decorative border, on the wall of his descendant’s study. A novelist would have married the lady to the gallant Rederick, but there seems to have been some objections te this romantic conclusion. Polite Custom in Sweden. It is the custom in most countries in Europe to hold the hat in the hand hile talking to a friend. In Sweden, to avoid the dangers arising from thia during the winter, it is no uncommon thing to see announcements in the daily paper informing the friends of Mr. So-and-So that he is unable, through the doctor’s orders, te con- form to this polite usage ‘