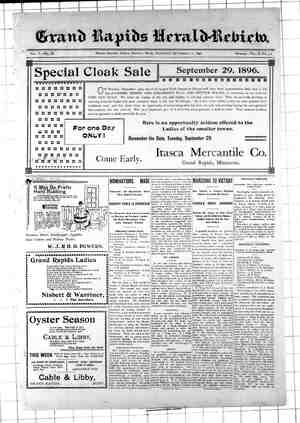

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, September 12, 1896, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

ee ee Se ae a So ae {HALL TELLIIH ONLY DAUGHTER. Aah ba bAbbadbih dh hbh be: CHAPTER XI—(Conteinued.) “May,” said Matthew Rivers, “a week ago I told you of the critical con- dition in which I was placed for want of a certain sum of money. You ‘told me that it was possible that you could obtain the means to help me, Have you done so?” sobbed poor Bs May; “I have failed.” “And do y er way by Ww poverty and di ae John Gridley rose, and, going > windo drew back the cur- »d out into the black, 1 remember the only oth- ich I 1 be rescued from remember, father.” “John has spoken to me since,” con- tinued the maltster, “and tells me he feels confident that he can succeed in making you love him, should you ac- cept him as your husband.” ay shook her head despondingly. y, darling, reject him— do not. for a fancied dislike, turn your father out in the world to begin life fatthew, Matthew,” said Mr ‘do not pr our daughter a union that is distasteful to her! “You do not know what is at sta said her husband, angrily. “Are prepared for mi leave Annadale d “Mother,” said May, you and poverty ?—to graced and ruined?” “it is not my father who would force me, but John Gridley. He it is who has the power to free father from his embarrass- ments, and who mekes my hand the condition upon which he will do so!” John Gridley turned and spoke: “Let me say a few words,” he ex- claimed. f it seems cruel on my part to make such a condition, it is my love which smet>it. I have loved May eve ce I have been in Annadale, and it Las ever been the dear wish of my life to make her my wife. If I were not confident that I could succeed in obtaining her love, I would leave the place at once; but I am sure that a life of devotion, a long- ing to gratify her every wish, and the true and ardent -:ffection which I feel for her, cannot fail to bear fruit in due season! Say, May, dearest, that you will not reject me, and make your parents as well as my . happy There was a dead silence of moments’ duration, and then Gridley resumed “T have but little to offer you in worldly gwds. The thousand pounds which will free your father is all I possess; but I >ffer you a stainless hand and an konest heart.” s, With calm, unblushing face, he said these words, a vivid flash of light- ning, followed by a terific thunder- clap wh.ck shock the house to its foundations. darted from the sky. John Gridley ceeled back in terror. It seemed to him as a sign of heay- en’s anger at his sin, and it was some moments before he resumed his ordi- nary composure. It gave May time for reflection ;and as she rapidly reviewed all the cir- cumstances which rendered it neces- for her to return him a favorable she resolved to sacrifice her- her father. She was unable to interpret her lover's silence; and the doubt of him which that silence had caused to creep into her mind, made her feel that all hope of marrying Ernest Hartrey was at an end. Her love for him had been a bright dream, but now she had awakened to the stern realities of life, and it was her duty to serve him to whom she owed her being. Slowly she rose from her seat and advanced to wher the maltster’s clerk stood with blanched cheek. “John Gridley,” she said, giving him her hand, “I rill do my best to love you and make you a good wife. At present, it seems all but impossible; but, with heaven’s help, you shall ney- er regret lage with me.” The rain came pattering down, and the thunder growled, as, overcome by her emotions, May sank back sense- less in her chair, some John CHAPTER XII. Anywhere Out of the World.” The struggle had been almost more than May could bear; but she had re- solved to go through with it—to drink the cup to the dregs; and she man- aged to give herself sufficient strength to make that little speech to John Gridley. No sooner were the words uttered, than the reaction took place. She shuddered as she thought of them, and the remembrance of Ernest Hartrey rushed with renewed force into her mind. She loved him and only him, yet she had promised her hand in ma e to another. The agony was dreadful, but uncon- sciousness relieved her sufferings for awhile. But the next day—oh, that was the most dreadful that May had known in her short life. The sharp, agonizing pang was over, but in its stead there came a dull, heavy, aching pain, as now, compara- tively calmly, she could think of what she had done, and the full force of it appeared glaringly before ber. Was there no relief for her? Was there no way in which she could es- cape from the dreaded marriage? Yhen her thoughts wandered to where a quiet little pool lay nestling under the hills, overshadowed by tall trees; and as she looked from the win- dow, the moaning wind seemed to bid her to fly thither for relief, and the branches of the elms nodded and beck- oned to her to leave the cottage, and find rest and peace forever in that still water, which mirrored the clouds as they went racing across the firma- ment. Yes, there she thought she would find relief, for thither they could not follow her. What would be her fate if she sought wilfully her peace in death? She covered her face with her hands and wept for the sinfulness of her “Anywhere, thought; but still the wind moaned in her ears “Come, come!” And_ the thought of that quiet pool would not be banished from her mind. V she not deserted and friendless, for who was there now to whom she could turn for comfort and support? Forsaken by Ernest Hartrey—aban- doned to the fate she dreaded by her father—her mother—little more than a and John Gridley resolved, at rd, to make her his wife! She was alone in the world, with no relief from her sufferings but death. Sleeping and waking, the thought of that ¢ ', still pool was ever present in her min Tor two days she struggled resolute- ly against the feeling—combatted the longing for death—and argued with herself of the sin of self-destruction; but the agony of mind which she was in, and which time could not assuage, was too much for her to bear. Her burden was too heavy; and on the morning of the third day she left her father’s cottage, resolved never again to return. It was no sudden resolution formed in the wild delirium of despair. It was the result of thought and reflee- tion as calm as her anguish would per- mit. The world seemed to her but a dull id, in which she could not live. To her allotted ys on earth as the wife of a man whom she more than disliked—to surrender herself to him, was a more dreadful fate than she dared contemplate. Poor little thing! Her heart was well-nigh broken! She was not strong- minded and hard, but a loving, tend hearted, crushed and disappointed girl, with nothing to look forward to, noth- ing to live for. She did not hide from herself that it was a great sin which she contemplat- ed. She had been well educated, and she knew that such an act must offend the Supreme, who, in His infinite wis- dom meets out the length of days either of joy or suffering to his creatures. She knew this, and it made her wa- ver in her determination, till, as if the floodgates of her mind were opened, a torrent of bitter thoughts and painful anticipations rushed on a headlong sweeping with them, annihilat- nd obliterating her better nature. lt is a favorite theme with many that ‘e in- $ suicide and temporary insani separable; and certainly poor Mar mind must have been in a sadly ¢ ordered state before she could hi brought herself to think of self-destruc- tion as a relief from he ufferings; but the thought was there, and would not be dismissed. The desire to escape from life, re- ardless of the future of another world, yas strong upon her. Perhaps she hardly realized what it was she contemplated—perhaps it was but a girlish fancy, which the sight of the pool would cause to disappear; but be that as it may, when she descended from her own room that dreadful morning, it was with the determination that ere night came again she would sleep the sleep of death, cradled in the moss, with the transparent water lap- ping gently over her, and none but the birds to sing her funeral dirge. She had intended writing a farewell letter to Ernest Hartrey; but then, she thought, why should she send him what would read like a reproach? No—it would be better she should die without a word—that he should forget her—perhaps never care to inquire aft- er her, and in the course of time marry some one more his equal in rank than a maltster’s daughter. Little did her mother know the rea- son of that tender, loving embrace with which her daughter bade her adieu; lit- tle did her father comprehend the meaning of her more than usually af- fectionate words to him. They saw she was sad and melan- choly, but neither guessed to what a pitch of despair she was driven. Out she went into the open air. The cold east-wind blew blightingly around her, the dead leaves whirled in eddies en every side, and the bare branches nodded and beckoned to her as they had done when she looked at them from her bedroom window—the window of that room which she had resolved never more to enter alive. Would they carry her thither, she wondered, when they found her? She pictured the scene to herself, and did not shudder, for she felt that she should be far beyond the grief and an- guish which now tormented her. She walked quickly on, hardly notic- ing the looks of those of her neighbors whom she met, and who stared after her amazed, for she walked rapidly, and returned no answer to their greet- ings; and they saw, by the expression on her face, that something out of the common must haye happened. May had soon passed through Anna- dale, and was out in the open country, come after the bustle, turmoil, grief, disappointment, and dispair of the last few days. No good angel was there to whisper words of comfort and consola- tion, te dry her tears, and bid her hope. It was rather a demon who walked by her side, reminding her of the hateful fate from which there seemed no es- cape, but in the eternal rest, and urg- ing her onward, and still onward to seek relief in death. As she approached the spot upon which she had fixed for self-destruc- tion, she saw a carriage drawn by two horses rapjdly drawing near. With a natural dislike to facing her fellow-creatures in such an hour, she got over a stile, which led by a path from the road by a somewhat longer route to the little pool in whieh she. longed to end her misery. It took her but a few minutes to reach the secluded spot where two little streams, rising in the hills, met in a natural basin. It was a lovely spot in summer, and May had often walked thither in the cool of a hot day, and found peace and rest in sitting on a mossy bank, gazing at the.placid water. The habit was strong within her, and she seated herself for a few moments; but rest produced thought, and the events of the last few days aroused her again, as they crowded inte her mind, and, rising, she ran to the water's edge; but ere she could cast herself into the pool, a gloved hand was laitt upon her shoulder. Frightened and alarmed, she turned and confronted a well-dressed, middle- aged lady, who regarded her pityingly. | “My poor girl!” said she, in a voice of compassion; “fall down upon your | knees, and thank heaven that you have | been preserved from the commission of | a dreadful sin.” For a moment May stood erect, al- most defiant, as if questioning the right of her who spoke to interfere; but it was only for a moment; for then the done smote her brain, and, casting her- self upon the turf, she sobbed as if her poor little heart would break. The strange lady made no effort to | check this outbu: but waited, still re- | garding her lovingly and kindly. As May became mere composed, the lady seated herself by her side, and | gently drew the poor girl towards her till her head rested en her shoulder. “Now, tell me,” said the stranger, caressingly, at the same time smooth- ing May’s beautiful hair,—‘tell «m what induced one so young and so fair a8 yourself to contemplate so great a sin “Oh, I cannot—cannot tell you! I am miserable and wretched! My father would force me to ma » and——” “And you don’t like his choic “No—oh, no!” said May, shuddering. “But I cannot tell you all. I am not at liberty to refuse this man, yet-——” “Yet you love some else better. See, I have guessed your story, and after all I do not see that you need have de- spaired. Tell me your name?” “May Rivers.” “May Rivers!” exclaimed the lady in amazement; “my poor, poor Me she muttered soothingly, partly to herself. After a few moments’ pause, she re- sumed. “You will never guess who I am, nor my object in doing so; but my drive to Annadale was for the sole purpose of seeing you.” “Seeing me?” echoed May, astonished in her turn. “Yes. My coachman was doubtful | about the road; and as I saw you get- ting over the stile, I left my carriage and followed you, to inquire the way to the village; and overtook you just in time to prevent you from doing that, at the recollection of which I am sure you now shudder as much as I do.” As she said this, she bowed her head and kissed May tenderly on the fore- head. “You are said Ma “Now promise me one thing,” she said, taking the poor girl's hand in her own. “T will promise you anything; it is the least I can do in return for your goodness.” “Promise me, then, that whatever may happen, however much you may be inchned to despair, that nothing shall ever again tempt you to think of self-destruction as a means of escape from misery.” “I promise.” very—very kind to me, ly and truthfully with her beautiful eyes at her rescuer. “T believe you; and now, as my coach- man will think I am lost, walk back with me to my carriage; and as we drive along I will tell you the reason that brought me to Annadale, and why I wanted to see and speak to Passively, May suffered he led back to the road, and to be assisted into the carriage. The lady gave directions to the coach- vly along the road man to drive slow towards the village, and then, seating sessing herself of one of her little hands, she commenced her promised explanation. I am the aunt of Ernest Hartrey.” bring me news from him. Say he has not deserted me—not forsaken me!” and she laid her hand upon Miss Hen- wood’s arm. “I fear, dear, I have but little com- fort to give you. None of us know where Ernest is—he has disappeared.” “Disappeared—disappeared!” repeat- ed May, like one in a dream. “Tell me, May. Did you write to him, asking him for the sum of one thousand pounds to save your father’s credit, and your marriage with one who was hateful to you?” “Yes—yes!” “He could not get it from his father, for they had quarreled, and he came to me.” How good, how kind of him—oh! y did he not write?” “Then’ you have never received the money ?” “No!” said May, surprised: ‘was it sent?” “It should have been.” “Where is it?” “Nay, do not ask me. Since Ernest Hartrey left my house, none of his relations have seen him.” “Some accident has Speak—tell me what it is? I will go to him at once!” exclaimed May, with such ‘vehemence as to startle Miss Henwood. “I know nothing of him—nothing!” she ejoined. “But wait, and hope that time may clear up the mystery, and that he may return—” “Return to find me the wife of John Gridley!” And May buried her head in the cushions and sobbed aloud. After awhile Miss Henwood drove her back to the outskirts of Annadale; Ww adieu, went back to Blackrock, while May walked on to her father’s house, with hope just alive in her bosom. CHAPTER XIII. Treats of Various Members of the Hartrey Family. Miss Agatha Henwood had given May some faint hope that Ernst Hart- rev might return and claim her for his wife; but she had done it more out of pity for the poor girl than from ary belief that the hope could ever be renlized. Where was Ernest Hartrey? That was the question which May asked so often without obtaining any satisfactory reply. Agatha Heuwocd was called sharp and snappish in her manner; and so she was to some; but to May she was kind and tender as a mother. Agatha Henwood was called sarcas- tic, and was supposed to delizkt in cruel speeches; aud certainly shc had the art of saying disagreeable things to those who annoyed her, but with knowledge of what she would have | As May spoke, she looked up fervent- | herself by May’s side, and again pos- | “My name is Agatha Henwood, and | “Oh!” cried May, eagerly, “do you} happened! | and then, bidding her an affectionate} | 4 May she refrained from breathing a suspicion which had entered her mind, because she knew it would dis‘ress the poor girl, whose burden she knew was already almost more than she could bear. Miss Agatha Henwood did not hear of her nephew’s disappearance till a week had elapsed since his visit to her; but no sooner did the news reach her ears than she ordered her carriage to be got ready, and caring nothing for the cold reception she was likely to meet with, drove over to Hartrey Park to call on her brother-in-law, Sir Harold, and makefMaquiries as to the truth of the report which had reached her ears. es She was shown into the baronet’s study. He rose and bowed stiffly as she entered. “Come, brother,” she said, “it is but seldom we meet, but when we do let it be as relations;” and she extended a hand to him, which he held for a mo- ment in his and then let drop. “The pleasure of seeing you, Agatha, is so rare that I may fairly ask what it is which has brought you from Blackrock?” “TI come to talk to you about your son.” “I have nothing to say respecting him. I know nothing of him.” “Nay, Harold, do not speak so eoldly and_ indifferently of your only child. Is it true, that which I hear, that he has disappeared?” “It is true.” “Have you taken no steps to dis- cover his whereabouts?” “None.” “Kind loving father! How he must be pining to return to you!” “Agatha, you shall not take his part against me in this house, at all events. He was dolt enough to reject a most flattering invitation from Lord P chester, and to refuse compliance my wishes on other matters- then I have heard nothing of him.” “I have, then, seen him since you.” “Indeed!” “Have you no curiosity to learn what have to tell?’ “None. Until he returns to me hum- bled, and prepared to marry whom I choose, giving up all notion of a wretched peasant girl, with whom he fancies himself in love, I have no wish to see him.” “Listen, then, to me, Harold. I hold it that marriage is too solemn a thing to be treated solely as a matter of con- venience. I have mixed in the world, and know the advantages and disad- vantages of such a union as you pro- pose for your son.” “Excuse me, I have no wish to dis- cuss the question with you.” “Perhaps not—you were neyer prone to take advice; but I have something to tell you.” Sir Harold leant back in his chair, with a sigh of resignation. “Your son came to me, and told me of his love for her whom you choose to designate as as a wretched peasant girl, and at the same time begged me to supply him with a sum of money to be devoted to a certain purpose.” “J have nothing to say to any money transactions between you. He is of age; I am responsible for nothing.” “I know you well encugh, Harold, to be sure that you would sooner part with your life than your money. Don't fancy I believe you capable of gener- osity.” roceed, ma’am, if you have any- thing to say.” “Only th that I advanced him the | money he required, and since then I e heard nothing of him.” “That is very likely.” “What do you mean? Surely you know more of him than you say?” “I know and care nothing of his movements; but as you appear anx- ious for your money, I will give you my opinion.” Agatha Henwood bowed her head. “My son had ever a taste for excite- ment and adventure. I believe he has obtained the money from you under false pretenses, and has left England in a fit of anger, and that we shall not see his face again till all the money is spent.” “I do not believe it.” “You are at liberty, ma’am, to be- lieve or disbelieve whatever you think proper.” “Then, Sir Harold, I tell you that I believe no one in England has so hard- hearted and indifferent a father as Ernest Hartrey.” “And I tell you, in turn, that I be- lieve no one in the world has so ob- trusive and impertinent aunt as my son.” Agatha Henwood colored, but made no rejoinder; neither did he reply to his visitor's adieu, but busied himself with a letter until she had left the room; and then he threw himself back in his chair; and as he thought of Ernest tears stood in his eyes—for his professed indifference to him s, in a great measure, only assumed in the presence of others, and in private he mourned for his dearly beloved boy, who had so unaccountably disap- peared. He was angry with him, it was true, for being so blind to his own inter- ests as to prefer the daughter of a malster to the daughter of a marquis, | and the affected indifference he ex- pressed when Miss Henwood men- tioned Ernest, differed widely from his true feeling un the subject. When he said he believed his son had gone abroad with the money ob- | tained from his aunt he spoke the truth. He thought that, angry and un- happy, despairing of ever obtaining his father’s consent to his marriage with May Rivers, he might naturally seek other scenes rather than those which would remind him of her he loved at every step. gatha Henwood saw the affair in the same way, and while she argued with herself that he had no reason to ask her for money for another purpose than that to which he intended de- yoting it, it seemed to be the far most natural solution of the mystery that he should have wished to quit Eng- land. After leaving Sir. Harold Hartrey, Miss Henwood drove into Portsmouth and went to the bankers to whom she had given Ernest a letter, requesting them to advance him the thousand pounds on the securiey of her jewels. ‘As the reader already knows, it was useless for her to inquire there. The manager of the bank summoned all his clerks, but they all denied haying seen Ernest Hartrey; and it was certain that no jewels belonging to Miss Henwocd had been deposited there. This was somewhat suspicious, con- cluded Ernest’s aunt. Had he meant what he said to her, | why should he have not gone to the banker's, as directed, if he were in such urgent need of the money as he represented? By dint of repeated questioning Miss Henwood ascertained that her nephew had been seen in Portsmouth late on the night of the day he left Black- vock; and thus she satisfied herself that he had had time sutflicient to visit the bank and obtain the money had he been so disposed. How was she to know of his deten- tion on the road? Who was there to tell her of the accident to his horse? Quite by chance, before she left Portsmouth, she met with a man who knew Ernest Hartrey by sight, and | who had seen him an hour later in the evening than those with whom she had | hitherto conver: “In what direction was he going?” | she asked eagerly. Jown tow: plied the man, anxious to tell |knew. “He stopped me | the way to Morten’s Qui “What boats go ire “Well, ma’am, I y say; y evening there was one | he channel to some place | rd the sea, ma’am,” re- all he but that vei | sailor talking and grumbling and ing they were waiting for some on “Thank you, my man—thank you!” Miss Henwood’s doubts were being rapidly confirmed. “Home, John,” she said to the cos rman; then, leaning back on the cushions of her carriage, she indulged in meditation, which lasted till the carriage entered the grounds of Black- | rock, Ernest’s disappearance seemed to her to result from one of two things. Either he had gone off to the con- tinent_with her jewels, or else he had displayed them to seme one who had } put him out of the v by violence in order to obtain po: ion of them. If the latter, surely his body would | have been found and recognized. Such | | not being the case, there was litile reom for doubt that Ernest Hartrey had left England, appropriating her | jewels to pay his expenses. She was bitterly grieved—more than | she cared to own, even to herself. | The loss of the trinkets did not | affect her greatly, but the deception which she believed had been practiced } upon her grieved her very much. | Ernest had always been a_ great | favorite of hers, and she could never } |have believed him guilty of such an ot that of which she now men- ott She resolved to drive over to Anna- dale at the first opportunity to dis- cover Whether such a person as May Rivers really resided there; for she thought it possible that her nephew might so far have deceived her as to linvent a touching story of his village llove as a likely means by which. to ex- | tract the money required from her. | Then followed Miss Henwood's visit | |to Annadale, and her fortunate meet- jing with May, in time to save her from the committal of the deadly sin which she had contemplated. The good lady kindly forebore to mention to the sorrowing girl the | doubt, which in her mind was almost having left the country of his own free will. Still there was a doubt, and she gave May the benefit of it and talked to her as hopefully as she could of the future; when he she loved so well | should appear again to claim her for his bride. Above all she urged her to postpone her marriage with John Gridley till the last minute. This, thought Miss Henwood, could do no harm; and besides, she still nourished in her heart a faint hope that, after all, her nephew was not so bad as circumstances made him ap- ° % i>] pear. “He may come back,” she mur- |mured to herself as she drove to Blackrock after leaving May; “he may come back and explain everything; and then, in the whole wide |world there will be no one to gave him a kinder, warmer welcome than his aunt Agatha.” And how fared it with Ernest Har- trey? He was working as a common sailor on board his majesty’s ship “Osprey,” fretting and fuming, as a fair wind took him farther and farther aw from the land in which he had left al that was dear to him. He had taken the first opportunity of speaking to the captain, stating to him his name and position, and at the same time requesting that he might be sent ashore at once, for when he spoke the | ship ¥ not clear of the channel. Now Capt. Salt was one of the old- fashioned sea captains. A hard- mouthed, deep-voiced, many- man was he; with a broad back and 2 strong hand. In the management of a ship he was unrivalled; but he was somewhat of a martinet. “Dicipline,” he would ery, “discipline is the thing, sir! I’d hang up every lubber who disobeyed orders to the yard-arm.” To give Capt. Salt his due, in this case he spoke the truth. every breach of discipline, he awarded always the most severe pun- ishment the instructions would permit; but when eyézything went well, and his sailors were in good training, no captain in the navy was me ¢ good- natured, pleasanter, or better liked. ‘The Osprey was always in splendid condition, ever ready for sea at an hour’s notice; hence it was that she had been chosen to carry out import- ant dispatches to the West Indies, with the greatest speed. The order for the Osprey to get un- derweigh arrived at rather an un- fortunate time, for some men had de- serted, and the ship was shorthanded; and while the press-gang was sent asore to obtain men, time was lost; and Capt. Salt was by no means in the best of tempers. His ill-humor had by no means sub- sided, when Ernest Hartrey accosted him on deck, and firmly, but respect- fully requested to be sent on shore. “If you go on shore, you'll have to swim for it,” said Capt. Salt, with a hoarse laugh, and one of his usual ex- pletives. “But my detention is have no right to keep me here. father, Sir Harold—” “Now look here, my fine fellow—I’m father, and king, and parliament, as long as you’re on board the Osprey. I don’t care a farthing’sworth of salt junk whether your father is Sir Har- old, or whether your detention is ille- | gal—I only know you'll have to obey illegal—you My | a stiff j and he felt that he had acted wrong- me; if you don’t, you'll be pué in irons; and if that isn’t enough, you'll be flogged—bear that in miud; and now go about your business.” “Capt. Salt, I must protest—” “You must do nothing of the kind,” said the captain, furiously; “the ship’s in a state of mutiny when fellows L you try to argue with your comm: ing officers. Be off—set to work tha or you shall dance to the music of the cat-o’-nine-tails.” What could he do but obey the cap- tain’s mandate? He argued with himself correctly, that if he must go to the West Indies, he must; and that it would be pre- ferable to make the journey working hard and at liberty, to passing the many weeks shackled and cramped in the hold, with nothing but his own dis- mal thoughts to pass the time. Accordingly he set to work with as good a gr: as he could, and soon learnt sufficient of his duties to ke himself useful. The hardships with which he had to put up. however, were great. The food and the sleeping accommodations were far different to what he had yeen accustomed; but there was noth- ing for it but to act up to the whole sea maxim, and grin and bear it. The only relief from the monotony of his employment—the only respite from the low conversation of his mess- mates—was when the lieutenant who | had rescued him, and who was indeed | no other than Rose Deacon’s quondam lover, could find time for five-minutes’ | chat with him. The relief to Ernest’s mind, the pleasure of conversing, if only for a few minutes, with a well educated gentleman, made him eagerly seek every occasion of exchanging a few words with the young officer. Capt. Salt disapproved of these con- versations as being! contrary to disci- pline, but he did not interfere to pre- vent them; for when he had somewhat cooled down, when he looked about him, and saw everything trim and taut, and when he felt the good ship he com- maded careering gallantly along before breeze, his ill-humor vanished fully to the gentleman whom a strangs fate had sent on board his ship. Apart from those with whom his lot ast Ernest might have enjoyed ze had he been able to forget those whom he had left in England; indeed, as it was, there were moments when the fresh sea breeze made his spirits rise, and exhilarated his whole hature. As H. M. Osprey scudded before the wind, with all her sails set, rising and falling with the deep, blue waves, which spread themselves white-crest- ed in every direction as far as the eye could reach, he felt something akin to pleasure rising in his br t It was a delightful sensation. The bright above and the bright sea below looked gay and cheerful; and had he been but able to let May know of his whereabouts he would have been happy. Again and again since he had beep on board ship had his thoughts turned with painful inte and inquiring anxiety to the events of the last night he had spent in England. There was so much that required ex- planation. That man who called himself John Gridley, who was he? His manners and education were aot those of a farm laborer, yet that was what he professed himself to be. And that man—that | had sought to take his life. Was it merely for the sake of the money? Or was there some other dark and hidden motive? It was strange, thought Ernest, that May should have entrusted her letter to such a man. Oh, if he could but see and talk with her, were it only for one short hour—could he but hear reas- suring words from her—could he but know that she had received the money! But, no; it was an impossibility—for the fast sailing Osprey was taking him every moment farther and far- ther away, and he had no means of communicating with her. He scanned the horizon again and again, for the first distant view of land, or a glance of sunshine on the sail of a homeward-bound ship; but nothing but the vast expanse of danc- ing, glittering waves met his eyes. In that ship he was pracvically alone, for there was no one to whom he could confide his doubts, hopes and fears—no one of whom he could take counsel. Lieutenant Steele was his good friend, and procured him many indul- gences; but still he was not a man on whose judgment Ernest could rely; and he hesitated to tell him the story of his misfortunes; and finally deter- mined to keep them confined to his own heart until he could return to England, and there make personal in- quiry, if necessary calling in the power of the law to come to the bot- tom of the mystery which perplexed him. Bright, hot weather, a scorching sun, a cloudless sky—all proclaimed the near approach of his majesty’s ship Osprey to tropical regions; but still on, on she went, day and night, cleaving her way through the bright clear wa- ter, which bubbled, foamed and dash- ed in clouds of spray beneath her bow. The nearer they approached their destination the more restless and un- easy became Ernest Hartrey. He longed inexpressibly to hear tidings of his darling May—to learn the clue to the many strange thoughts that perplexed him, and to claim her before the whole world as his wife. He felt confident that John Gridley had purposely pushed him into the sea; but yet it would be difficult to prove it. But if he had intended to drown hi it was certainly with the design of eS propriating the thousand pounds. A now the question which was contin- ually arising in Ernest Hartrey’s mind was, whether May had ever received the money. If not! He shuddered as the al- ternative presented itself to him. Should he, on his return to England, find the old malster driven from his home, and his daughter already a wife? for that was what her letter had had led him to believe would be the result of her not obtaining the thous- and pounds. “Sail on the port bow!” sung out the look-out man, as one day Ernest, lean- ing against the bulwarks, was indulg- ing his gloomy thoughts. . _| (To Be Continved.) z