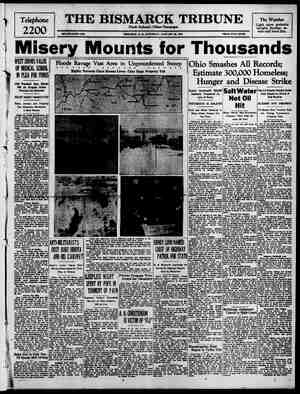

Evening Star Newspaper, January 23, 1937, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Books—Art—Music GRIPPING EVENTS IMPRE * h 4 FEATURES Foening Stap WASHINGTON, D. C., SATURDAY, JANUARY 23, 1937. SS PERSONALITIES ARE STRIKING Bill Coyle, Famous in His Own Right, Has Had Opportunities to Observe Men and Women of Modest or Aggressive Type Who Have Won the World’s Applause. Bill Coyle is the National Broadcasting Co.’s celebrated sports announcer, who has been attached to WMAL for three years. In that time he has interviewed many per- sonalities of sportland. This story records their reaction to the delicate little micro- phone. By Bill Coyle. OW do the base ball, foot ball, tennis, golf and other sports stars act when you get them on the radio, you ask? Well, they don't all go over with a bang on the air, but from my own experience | in chaperoning to the mike many of the big shots of sportsdom who have appeared in this vicinity, I'll say they have the edge on most of the folks who think that all they need is one audition to break into the networks. Most of the athletes who amount to anything in their line have ample op- portunity to exercise their talents on the air these days, for they are much sought after by the radio interviewers everywhere. that they are very willing stooges for the mikeman and that takes plenty cf patience at times. Ever since the 20s, when the radio YMsteners started insisting on hearing foot ball, base ball, golf and tennis matches, racing, prizefights and other sports spectacles While they stretched out in the old armchair, a new art has been developed in broadcasting. The sports fan, the armchair halfback and the cracker barrel base ball manager | wanted to see with their ears, and it was up to the sports broadcaster to make them do it. In the beginning, sports broadcast- fng was a stunt. A big game or event was described by the studio announcer available at the time, but it didn't take long for the fans to see the flaws of this method. The fans demanded the same kind of reporting over the air that they got in the sports pages. That is, they demanded an expert. They didn't want or expect the same kind of a story. They wanted to read that by their fa- vorite writer, but they did want some- body on the job who knew what was going on. THAT was the first step. The sports 2 broadcaster was developed. Then eame another step, the natural de- mand of the listener to get a chance to see with his ears the contestants in | ¢he sports world themselves. That's | what brought about the air interviews. | It was in these interviews, from time | to time, that I began to realize that| sports broadcasting wasn't all records, | touchdowns, hits and errors, birdies, | volleys, triumphs and defeats. | In many respects, my job as & sports | announcer has been comparable to| that of the sports writer, but when it comes to interviewing a sports celeb- rity, the comparison with the sports writer ends. The sports big shot may be so dumb that even his manager ean't make him talk and so does most of the talking for the athlete, but the sports writer sill has at least two fin- | gers and plenty of copy paper. It's a different story when the little green | light turns on and it's time to go qn; the air. It's a feeling hard to explain | when you're sitting across the table | from hurly-burly Joe Doakes, the in- | ternational something or other cham- | pion. There’s no time for the blue | pencil, no time to look up last year's record. And the surprising part of it all is that the guy in most cases makes good. And what a relief when he does. Phew! I the one being interviewed as human | as possible. You may know the thrill- | ing story somewhere behind that par- | ticular crack of the bat whose echo| has hardly died, that particular thud | of the glove that did work a few min- | utes before, or the touchdown that won the game or any other of the split seconds that set the bleachers | roaring. You may know that story. | The hero of the dramatic incident | knows the story, but try to get it out | of him! Sometimes it's modesty, sometimes {t's just plain stage fright, and some- | times it's just the old vacuum up | there over the eyebrows that figures | in the procedure. But often the story | eomes out, just as easy and natural | as when grandpa tells how he rode | the horse cars. On the whole, however, I have found, through personal contact with some of the foremost athletes of our day. that as a group the lads that puff and strain and punch and groan cannot be beaten in their high regard for ac- | complishment in their line, and true | sense of honesty, and the rewards of diligence and strict training. But, like the people that you rum across in every walk of life, the athletes run the gamut from A to Z, beginning, perhaps, as I have found it, with the sobriety of certain well-educated fig- | ures, such as Glenn Cunningham, the | famous Kansas miler, and ending with the loquacious, linguistic fluency of ' Kingfish Levinsky, the heavyweight. I am going to start the local sports picture off with the No. 1 personality of them all—Clark Griffith, the Old Fox. It was at the beginning of the last base ball season that I first had the pleasure of introducing Clark Griffith over the air. The Washington base ball club president, the only man in the big leagues today who has risen from the dark dusty dugout to the sparkling mahogany desk of the front office, is numbered among my most prized guests. He preferred to read his remarks about his ball club, jotted down in his own hand. His voice was firm and filled with assurance as he prophesied that this year he believed he was giving the Washington fans one of the fightingest ball clubs in his reign at Florida avenue. And how true he was as the Nationals thundered down the stretch, to finish in the first division, upsetting all the dope. I couldn’t help but be impressed by the Agact that seated there at the mike was s man of half a century of experience | THINK the biggest job is to make ‘ At least I have found | in base ball, in every capacity from player to club president, his kindly face aglow with the light of & man who has lived life squarely, cleanly, | and with charity in his heart. NE of the best radio voices be- longs to an athlete who chirps "| through the size 14 collar of Bucky Harris, fighting manager of the Wash- ington ball club. Buck's diction is perfect, and he is one of those sports celebrities who could easily cop off a broadcasting job. What I liked about my interview with Bucky was the de- liberate manner in which he answered my questions. You know when I in- terview some one I usually find my- | | self reading his character by studying | his mannerisms before the mike. | Bucky's attitude and reaction in the | studio stamped him, in my mind, as a fellow who really knows what he's talking about, and has plenty of stuff | up there underneath that wavy hair. I recall the evening that the great- est ball player of all time, the massive Bambino, Babe Ruth, strode into the | studio. Of course, I was so tickled that I could hardly talk when it came time to go on the air, and there wasn't & happier guy in the world when the Babe gave me his autograph after the broadcast. At that time, he | was in the twilight of his career. Sports writers and columnists were all speculating on just when the Babe was going to come right out and say he was through. Of course, he was making no public statements | as to just when that day would come, for obvious reasons. But he gave over and he started to hoist that massive frame of his to his feet. He groaned under his breath as he flexed his legs after those several minutes in a chair, “I guess the old pins are | just about gone.” There was an un- mistakable tone ot disgust and, more than that, of total resignation in his | voice. Soon after that, he went to | the Braves and subsequently an- nounced his retirement. [ One of the broadcasts that I will {long remember for sentimental rea- | sons was the one in which Mr. and JMrs. Batting Champion of 1935 par- | | ticipated. Of course, I refer to Mr. |and Mzs. Buddy Myer. Buddy, harp- | playing captain of the Washington ! ball club, had just won by a mere percentage point the American League batting crown. When he re- turned to Washington, his thrilling triumph having taken place while ' the team was on the road, Buddy and his charming little wife, Minna, kindly consented to come to the N.| B. C. studios and allow me to con- gratulate them in the name of the listening base ball fans who had been following Buddy's unforgettable fight. His wife was so excited at her hus- band'’s good fortune and the undying name he made for himself in base ball history that there were tears in her eyes as she stepped to the micro- phone to relate how she felt on that occasion. The best line of the broad- cast came when I asked Mrs. Myer what she had done to inspire her champion to the heights he then en- joyed. She beamed through her moist eyes and with Washington listening me an inkling after the broadcast was | n remarked, “I just kept him atuffed full of my good ol’ fried chicken.” NO ONE in the world punishes & mike the way Washington's peer- less boxing matchmaker does. In the studio, Goldie Ahearn is as mo- tionless as a statue until he’s intro- duced to the radio audience. When the introduction is over it is then that Goldie leaps into action. He darts at that mike like & throat-parched desert wanderer at a mirage and subse- quently lets go a volley of verdiage’| that will knock you off your chair. When Goldie is through you are aware of three things—the silence, his shirt shop is full of unsurpassed sartorial splendor and every fight in his com- ing show is nothing short of a main event! But Goldie has applied the same vigor in making his matches, | which have been a credit to any pro- moter in the country. | Of course, heading the list in the | national boxing spotlight is Jack Dempsey. My first contact on the air with Jack came when he was grooming a young Adonis by the name |of Maxie Baer, With thousands of | listeners waiting to hear from the | voice behind the fist that had rocked the world, Dempsey, the most color- ful figure in modern prize fight his- tory, piped in his peculiar falsetto, “And standing right beside me, folks, |is your next heavyweight champion | of the world, Max Baer.” That was another microphone prophesy that came true. | Yes, the boxing world has been full of colorful personalities. I mustn't forget the present heavyweight cham- pion of the world, Jim Braddock. Jim isn't a very fluent performer on the radio. He doesn’t care much for per- forming in any way, and perhaps that's the reason why he has seldom i been seen in public outside the ring. Jim's business is fighting, and he's completely satisfied to allow it to re- main as such. However, I can still see | him crouched over the mike in one of | | his very few radio appearances, re- | plying in short, blunt sentences just | | how it feels to be a champ and how | “yesterday it was coffee and dough- | nuts, if we were lucky, and now it's | fat, juicy steaks 2 inches thick.” 'HE greatest interest in a fighter | was probably evidenced when Joe Louis, the present sensational con- tender for Braddock’s crown, came to | the N. B. C. studios. Of course, the | boxing fans had read in the papers | that Joe was going to be on the radio, | and a tremendous crowd turned out to see the big lad shuffle into the lobby of the Press Building. Hundreds of | people jammed and pushed for a view | | of the boy—so many, in fact, that Joe needed a police escort to get to the | elevator. He had been described by sports writers as “Dead Pan Joe.” He | was that, all right. Joe insisted on the studio being cleared of visitors be- fore he submitted to an interview, and didn't crack a smile until he was asked if he could knock Maxie Baer off his feet in their coming battle. Joe didn't smile, but he answered with unexpected dry humor: “I think | I can smack him down for 10 seconds. | That ought to be long enough, don’t | cha think?” & But it didn't turn out to be so funny | as far as Maxie was concerned. Joe knocked Baer out, as you already | know. I can tell you that sports broad- | casting is a thrilling and a delightful | experience. And there are many more | microphone scenes that will flash | across my memory in my old age, when | reflection will then be one of my sole | enjoyments. For instance, I will see Tony Can- zoneri, then lightweight champion of the world, singing in my mike in a husky, butchy baritone, of all songs, “Love Is Just Around the Corner.” | Tony was a bachelor then, and since | has married a chorus girl. Perhaps | there was more significance to his burst of song than I knew at the time. | AGAXN the scene changes, and this | time a tall, powerfully built girl | is chatting to the radio -audience. | She’s square-shouldered, and I even remember how she was dressed. She had an orange sweater on, and to complete her ensemble she wore a brown skirt and a brown felt hat pulled down over her left eye. Its Helen Stephens, who just a few weeks before had been standing on the champion’s platform as an Olympic winner at Berlin. She was the fastest | woman runner over the 100-meter dis- tance in the world. And there she sat, calm as a cucumber, telling her story of that Berlin scamper. The Olympic theme is still running | through my mind. Who is it now that | is smiling into the mike? Why, it's | Eleanor Holm, the queen of the back- | stroke. Beside her sits her bandmaster | husband. Laughingly they relate how their romance began on a blind date. Why, no, they're not nervous. They have just come from the stage, where | Eleanor’s singing is part of their act, | along with hubby Arthur Jarrett's | songs and band. Eleanor says that her favorite color is blue. Another day and another scene comes to mind. Dutch Bergman, you know, the coach of Catholic Uni- (Continued on Page B-3.) News of Churches PAGE B—1 BROADCASTER OF SPOR 1. Babe Ruth on the air. 2. Microphones don’t scare Helen Stephens, track star. 3. Pat Harrison presenting a diamond ring to Buddy Myer. On the right is Clark Griffith. 4. Dempsey is an expert broadcaster. 5. Bill g:wle broadcasting a mara- on. YOUNG SENATOR EXCEPTIONAL Family and Senatorial Traditions Are Mingled With Journalistic Utterances and His Critical Views as an Author—Henry Lodge Is Unique in Public Office. By Lucy Salamanca. HENRY CABOT LODGE, Jr., Massachusetts Republican neo- phyte in a Democratic Senate, has a double responsibility during the next six years—to keep faith with his own published views on public prob- lems and the qualifications of men and women for public office and to preserve the political prestige of the aristocratic tradition established by his distin- guished grandfather. In book and in newspaper, as a Washington ocorrespondent, young Lodge has placed his writing on the wall weighed by his own words. Discussing the need for trained men in public life in his book “The Cult of ‘Weakness,” published in 1932, Lodge said “able professionals” were, clearly, what the situation demanded. He ex- pressed the opinion that no branch of private activity or of appointive office can give a man the training for public life afforded by politics. Lodge, who served for five years in Washington as political news corre- spondent for the New York Herald Tribune, made the further observation that political journalism, “which un- dertakes to know the public temper,” is perhaps the closest approximation to politics. It is scarcely possible that | at the time of making that statement the new Senator from Massachusetts could have foreseen that his own journalistic ability might number him among the “able professionals” whose talents would one day be exercised in the Senate chamber. At the time of this writing Lodge deplored the presence of “midgets in the seats of the mighty” and the gen- HIRTY - FOUR - YEAR - OLD | | eral worship of expediency that dic- | tated too often the way in which a | Senator cast his vote. | | "It is unlikely that a man's view- points, gained in mature experience, | will change fundamentally over the | short space of five years. Thus, while | | Senator Lodge has given no expression | | since coming to Washington of what | | policies he may or may not pursue, a | very good idea of the trend of his mind | | on public questions may be gained from | a review of those expressions to which | | he gave utterance while still a journal- | ist. | As a matter of fact, the Massachu-. setts Senator drew attention to the fact that a politician must not only | know the people, but periodically must | | in short, do what no man enjoys do- | ing—commit himself in public. While still a journalist Lodge could “commit himself in public” with im- | | munity from comment or criticism. | Again, it is he who points out that if | the reader does not like what a po- | litical writer has to say, he may pass |on to the “funnies” and there need be | no hard feelings. | | AS & member of the United States Senate, Lodge will become in- ; creasingly aware of something he | knows already—that when a Senator | speaks the newspaper public gives his | statement no such fleeting attention. | Every word from this point on reveals a political philosophy or is regarded as an indication of whicix way he may be iexpected to vote for the electorate of his State and the Natiom, | The junior senator from Massa- chusetts occupies another unique po- | | sition in the interests of the American | people, for he brings with him the | entire weight of his famous grandfath- er's prestige, the shadow of that mag- GERMS HAVE NO CHANCE TO PASS GUARDS AT MEAT Sloping Floor and Rounded Corners Add Protection for Country’s Food. By William A. Bell, Jr. ERHAPS you've seen on a side of beef, on a ham or other cut of meat, in the market where you shop, a small inked circle in- closing this wording: “U. S. Inspected and Passed by Department of Agri- culture.” If you have a box of link sausage in your ice box you probably will find that the same legend is printed on the carton., Even if you have seen this stamped label it ‘may never have interested you much to know what's behind it. I had a faint curiosity, however, and went over to Baltimore to see how it's done— this meat inspection business. After watching the Federal inspectors at work, seeing their careful scrutiny of every procedure in the processing of meat, I knew the importance of that stamp as a symbol of health protec- tion. Not all meat is Federally inspected. Not by a long sight. But most of it is, thank goodness and our Uncle Sam. The iaw requires that all establish- ments doing an Interstate meat busi- ness have Federal inspection. Small local concerns can do without. The plant I visited, however, was a big one, and a great deal of the meat we eat in ‘Washington comes from it. THE Government officer who took me through the plant—he was a doctor of veterinary science—pointed to a group of workers in white frocks. The men wore visored white caps, while on the heads of women were starched white bands, He said the Government required thém to change these outer garments at least twice a week. “Furthermore,” he explained, “our inspectors are always on the lookout for any sign of illness among the em- ployes. If the notice any, they report it to the management, which assigns the affected employes to duties that won't bring them in contact with any of the meat.” I was introduced to one of the in- spectors. He looked like a factory worker, had on the same white frock and visored cap. Pinned half inside his breast pocket, however, was & nickel-plated badge identifying him as “U 8. Officer, Bureau of Animal Industry.” “He's a lay inspector,” guide. “The veterinary have badges liké mine.” & He showed me his symbol of thority. It was surmounted by. <pe said my inspectors 1 eagle and said “inspector” instead of | “officer.” “All of our veterinary inspectors are doctors. They have degrees in | veterinary science.” 1 noticed that the floors of the plant | sloped slightly and that there were no right-angle corners at the juncture of floors and walls. The chief in- spector explained the plant was built under United States Governmens spec- ifications, which insisted on sloping floors to allow proper drainage and on rounded corners to prevent accumu- lation of filth. “Look at those windowsills,” said my guide. “They are sloped under | our orders so that no one can leave anything standing on them.” TH!: same scrupulous attention to sanitation was evident in wash rooms and dressing rooms. Plugs have been removed from all the wash basins to prevent employes from drawing water. They must stick their hands under small sprays, many controlled by foot pedals. A special type of soap—Government approved—is used. The chief inspector took me to the box-washing room, where every box or barrel in which meat was to be packed was scrubbed with soda, rinsed under hot water and sterilized with steam. The boxes actually smelled clean. In another roem three young women were washing hog intestines to be used as sausage casings. They washed them with as much care as if they were baby clothes. The lay inspector said it was one of his duties to see to it that every inch of casing was handled in this way. The women wore aprons of yellow “slicker” material. The castags were slipped over a faucet and fllled with water. They looked like transparent white snakes. The water was squeezed out and the cas- ings were thrown in a tub. ® ‘We went into a chilly room where sausage meat was heaped in metal trays. It had been ground to the consistency of mud. The pork sausage meat looked like strawberry ice cream. Completed sausages, like rows of fat white fingers, hung on | racks, waiting to be smoked. The inspector said he saw to it that each batch of sausage was seasoned ac- cording to specifications, 7 b “For instance,” he said, “we only allow 3 per cent cereal in this kind.” The inspector watches, too, the temperature of the foom in which un- cooked sausages are kept. It must not be more than 34 degrees. N THE same section of the plant, 30 or 40 workers were standing at long tables, filling the sausage cas- ings with meat, tying the “wieners” or “franks” at proper lengths and stamping the long coils with that circular symbol of health safeguard: “U. S. Inspected and Passed by De- partment of Agriculture.” The chop- ped meat was shoveled into a cylindri- cal machine, which fed it through a nozzle into the casings. Spurting out; it Jooked like toothpaste being squirted from a giant's toothpaste tube. As the sausages were completed, sections of them were looped and placed into tin boxes or cardboard cartons. The boxes and the cartons likewise bore the Federal inspection label. Sausages of a variety that doesn't have to be recooked were racked in smoking cabinets over gas flames cov- ered with smoke-producing sawdust. The inspector opened one of these cabinets, took a thermometer from his breast pocket and stuck it through the skin of a frankfurter. We watch- ed the silver sliver of mercury climb to 157 degrees. “We make manufacturers cook any pork that is going to be used without further cooking to a temperature of| well above 137 degrees,” the chief in- spector said. “If they don't do this, then they must freeze all pork muscle tissue at 5 degrees for a period of 20 days or prepare this kind of pork ac- cording to other specifications of the Secretary of Agriculture. These temperatures—either 137 or S5—kill any trichinae, the germ that causes trichinosis. “Here are the company thermom- eters. We check them against our Government thermometers, which have been tested by the Bureau of Standards.” SLAUGm hogs, naked as a new-born babe and headless as Ichbad Crane’s phantom pursuer, came swinging down an incline, suspended by their feet from a hook-and-chain device. They had been split down the middle from stem to stern and their incides had been removed. The in- spector raught sight of one that had pushed aside from the rest. He took from his pocket & tag with the words, “U. 8. Retained.” “That hog’s fallen on the floor,” he said, sticking the tag iato the pig's bare side. “They’ll ‘have to clean i up properly before I'll pass it.” The tag also said, * article to which this tag 15 al shall be | This tag shall be detached only by | made sanitary before it is used again. an employe of the Bureau of Animal, Industry.” | I asked why the plant handler had put the questionable hog aside, inas- | much as the inspector had not been | there when the carcass fell to the floor. Why hadn't he just dusted it off and sent it along with the rest? “He wouldn't dare send it along. | He knows I'd catch it in the cooler | and then he'd catch hell. They clean the floor here every night, but that/ hog will have to skinned.” | ‘We went into a room where hog | carcasses were arrayed in parallel rows, extending far back int . the foggy darkness. I shivered ir. the damp cold. “This room is chilled tc take the | animal heat out of the carcasses,” the chief inspector explained. | | ASKED him how many hogs and cattle were killed in this plant each week. He said about 9,000 hogs and about 1,800 head of cattle. Nearly 700 people were occupied in slaugh- fat has been taken off the entrails. each organ is washed separately under that spray you see there. The in- spector here is a veterinary doctor. He can tell at a glance whether there's anything wrong. Go ask him what he’s doing.” APPROACHED an inspector. His uniform was freckled with blood. He said he was looking for cysts, prin- cipally. He found & Kkidney that seemed to be studded with jelly beans. “Cysts,” he said, and tossed the de- fective organ into a red barrel, a “gar- bage” barrel for parts that'must be reduced to fertilizer; that can never go out as food. The next stop on tour was the slaughter room. It was pretty awful. e tering and processing these animals for consumption as food. A big job | for the inspectors. | A substance which the inspector | L said was leaf lard hung on rows of | “hooks. It looked like tallow drip from | monster candles. Ten men were lzl work in the “boning room,” taking| bones from sections of hogs to pre- pare meat for chopping. The chief inspector led me to a “cell,” an area inclosed in heavy wire screening. This, he explained, was the “retained room.” He showed me the lock on the small cell door. It said: “Bureau of Animal Industry.” “Only our inspectors carry keys,” the | chief said. The “retained room” contained 10 hog carcasses bearing tags like the one I had seen the lay inspector put on the hog that had fallen in the floor. The inspector pointed to a bruised carcass. “Now if this plant wasn’t under our supervision,” he said, “they would just hack off the bruised parts. But you'll notice this carcass has been stamped, ‘U. S. Passed for Sterilization.’ It will either be reduced to lard or brought to a temperature of 170 de- grees for 30 minutes. This hog might have had localized disease symptoms. The diseased parts have been removed and it is perfectly all right, but just for safety we'll give it the heat treatment.” ‘The odor in that section of the plant where lard is made was almost over- powering, 50 I was glad when we left that for the place where cattle entrails were being prepared. An inspector was bending over a table, carefully ex- amining kidneys. Another was scrap- ing hearts, tongues and livers. . “We insist on this piecg inspection,” the chief inspector INZ “After the The floor was so slimy that it was almost impossible to stand and from off-stage came the bleats of the ani- mals about to become meat. Cows were coming down an inclined runway one by one. A young fellow with big biceps and & pale skin, whose pallor was accentuated by the splashes of blood all over him, was whacking the cows over the head with an iron mal- let. Down they'd go, unconscious, | and soon would be hauled up by their feet and stuck in the jugular vein with a long knife. Then they were beheaded, skinned and taken apart. East head was examined by a Fed- eral inspector, who also looked over each set of insides. The inspector probed among the glands in the rear of a dripping cow’s head. By doing ihis, he said, he could tell if the ani- mal had any signs of disease. He cuts into six different glands in each head and inot the muscles of the cheek. “Those are the muscles that do the most work and that's where tape- worm is to be found.” We went into a big, noisy room where the newly-killed hogs were be- ing disassembled. The carcasses would enter on an endless chain conveyor, pass through & scalding bath to loosen the bristles and be dumped into & device that stripped them of every hair on their bodies. When they came out they would be jerked up by the feet and passed slowly along on another endle:s chain conveyor, head down. A man with a huge, poaring blow torch PLANTS Management of Suspected| Animals and Accidental Defects Disclosed. sterilized each carcass with a blast of flame as the hogs came slowly by. ONE of the ever-present inspectors watched these processes from the | | beginning, examining each head as in the case of the cattle. “Look here,” he said to me, pointing | to some glands splotched with reddish brown. “Cholera. This hog's had cholera.” The inspector took out a tag with big black letters: “Condemned.” As this hog passed along the conveyor and, like the rest, was split down the middle and the entrails taken out, each part was stamped “Condemned.” Carcass, insides and all went down an inclosed chute to another “cell” like the one where they put the “retained” carcasses. The door to this caged in- clousre did not have a lock, however. It had a metal seal, The workman in- side, shoveling the condemned part into & surrendering tank, could not get out until that seal was broken official- ly by a Federal inspector. The seal cannot be broken until all the con- demned stuff has been reduced to fertilizer at a temperature of 240 de- grees. This takes three hours’ cooking. This account is backward. The first duty of the Federal meat inspectors is to examine the animals before they are slaughtered. The “ante-mortem” inspector, as they call the officer whose duty this is, must be at the plant at 5:30 in the morning to look over the hundreds of cows and pigs that will be made into beefsteak or bacon that day. He must go through the pens where the animals are placed when they are taken off the trains or trucks that bring them to the end of their trail. And if his trained eye sights anything “suspicious” he must put a metal tag in the animal’s ear, a tag that says, “U. S. Suspect.” After further examination, if the animal is found to be really ailing, it is disposed of and can never find its way, in whole or in part, to a breakfast or dinner table. The law which requires such de- tailed inspection is more than 30 years old. I didn’t know it and I bet you didn't, either. There are United States inspectors in about 350 communities, safeguarding the meat supply that comes from some 1,500 plants. After watching the inspectors at work I ate my pork chops for dinner 'H with a new sense of respect for & Government that provides such pro- tection for flu?fllfll of its millions. nificent legislator’s personality and the continuous consideration of compari- son. No matter how talented he may prove to be in his own rights, nor how distinguished a career he may carve for himself in Washington, there will always be those who will think that he is either a little more than or & little less than his grandfather. During the short time he has been in Washington Senator Lodge, while he has given audience to members of the press, has not as yet permitted himself to be quoted on the issues of the day. This is not difficult to understand. To ask the distinguished senator what he thinks of the neutrality pact, how the President’s reorganization plan for the executive departments and now the author will be | bare his soul to them; that he must, | strikes him, or kindred pertinent ques- tions, is in a way comparable to asking the new boy in the boarding school cloakroom to square X plus Y before he has had time to hang up his hat. After all, there isn't a great deal of ‘.dmerence, from the standpoint of the newcomer, in entering boarding school for the first time and having to learn the ways of the older boys and taking one’s place in that charmed, if individ- ualistic, circle that comprises the Senate. This, however, we can say of Senator Lodge on first-hand authority. He has the “Harvard handshake,” plus a little added assurance, which seems to have resulted from his journalistic career. A vim, a heartiness, a suavity, abun= dance of poise and pronounced talent for contact with his fellows are com= | bined indications of his cultural back=- | ground, traditional heritage and avo- cation. Ever since we could read, of course, and our fathers before us, we have known about the “Cabots and the Lodges,” even if the familiar jingle had not additionally impressed upoi us the importance these family names have attained in New England. More specifically, Henry Cabot Lodge, senior, two generators ago dis- tinguished himself in literary and leg- islative capacities to such an extent that the refulgent glow of his achieve- ments shines even now in Washington. So much for heritage. Henry Cabot Lodge, jr., was born just 34 years ago in Nahant, Mass. He is nine years younger than was his distinguished grandfather when that gentleman en- | tered the United States Senate. Both these gentlemen were 30 years old when they first became members of | the Massachusetts House of Repre- sentatives, which the elder Senator Lodge entered in 1880. ENRY CABOT LODGE, JR, was educated at Middlesex School, in Concord, from which he was graduated in 1920. In 192¢ he received his B. A. from Harvard. While still in college, in 1923, he began his journal- istic career with the Boston Evening Transcript. Directly after his gradu- ation he became associated with the New York Herald-Tribune in an edi- torial capacity—an association which he has maintained up until the time of his coming to Washington this year, despite his political interlude as a State legislator. It was during the first part of his career with the Tribune that he had an opportunity to gain first-hand knowledge of how things were done on the “Hill” For five years he sent political copy to the Tribune out of ‘Washington. During his newspaper days he covered political conventions, affairs in Nicaragua and in Mexico and was foreign correspondent in Eu- rope and the Far Eastern tropics. Lodge became active in Massachu- setts politics when he entered the Massachusetts General Court, serving two terms and identifying himself with the Committee or Labor and Indus- tries as its chairman. Running against Gov. Curley, Democrat, for United States Senator, he polled 115,644 votes, against the Governor's 92,623. This was in the State. In Boston, Curley ran ahead of him by some 30,000 votes. A member of the State Legislature at the time of his election, the new Republican Senator and his wife were drawn out to parade the night of his victory by the home town folks of Beverly, Mass. Heading the proces- sion in an open car, they made their way in a motor torchlight procession to the city hall. Questions of neutrality, reorgani- zation of Federal departments and war debts continue to occupy the im- mediate attention of the Senate. These, it appears, are not new ques- tions, for they revive again talk of war and peace, arouse anew discus- sions of bureaucracy and bring up for review the entire matter of foreign trade and other international rela- tions. Five years ago, in his “Cult of Weakness,” Henry Cabot Lodge, jr., (Coni on Page B-2)