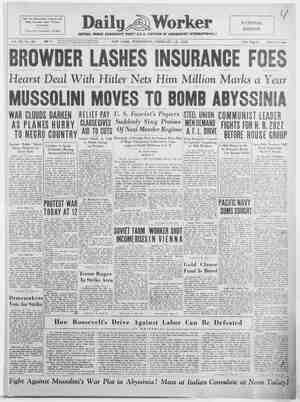

Evening Star Newspaper, February 13, 1935, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

FEP THE EVENING STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C., WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 13, 1935. A4 Judge Outlines Duty to Jury, Explaining ‘Reasonable Doubt’ Wilentz Heaps Scorn on Head Crowd Anxiously Follows Hauptmann Trial Of Hauptmann in Summation Copyright, A. P. Wirephoto. Trenchard Recalls High Points in Accumulated Tension of Court Grouws. Testimony, but Says Panel Must Decide Question for Itself. By the Associated Press. FLEMINGTON, N. J., February 13. —Justice Thomas W. Trenchard de- livered the following charge tocay to the jury trying Bruno Richard Haupt- mann for the Lindbergh baby murder: | Ladies and gentlemen of the jury: | The prisoner at the bar, Bruno| Richard Hauptmann, stands charged | in this indictment with the murder of. Charles A. Lindbergh, jr., at the township of East Amwell in this| county on the first day of March, 1932. It now becomes vour duty to render & verdict upon the question of his | guilt or nis innocence and upon the | degree of nis guilt, if guilty. In doing this you must be guided by the prin- | ciples of law bearing upon the case that I will now proceed to lay before you. In the determination of all questions of fact, the sole responsibility is with the jury. You are the sole judges | of the evidence, of the weight of the evidence, and of the credibility of the witnesses. Any comments that I may make upon the evidence will be made, not for the purpose of controlling you in your view of the facts, but only to aid vou in applving the principles of law to the f as you may find them. You must not consider what I shall say concerning the evidence as being accurate, but you must depend upon your own recollection. You must not only consider the evidence to which I shall refer, but you must consider all of the evidence in the case Innocence Presumed Until Shown Guilty. In this, as in every criminal case, the defendant is presumed to be in- nocent, which presumption continues until he is proved to be guilty. To support t ctment and to Justify a convic the State must prove the facts sufficient for that pur- vide asonable | | t burden never shifts If there be reason- able doubt whether the defendant be guilty. he is to be declared not guilty Reasonable doubt is a term often y well understoo fined. It is not a because every- from the State. ting to human affairs and | moral evidence is open possible or imaginary doubt. It is that state of the case which after the entire con son and co sideration of all of the evidence, leaves the minds of the jurors in that condi- tion that they cannot say that they feel an abiding conviction to a moral certainty of the truth of the charge, The evidence must establish the truth of the fact to a moral certainty, a certainty that the understand reason and are bound upon it. But if, after canvas carefully the the accused the bene- le doubt, you are led to the conclusion that the defendant is guilty, you should so declare by your verdict. Must Establish Case Beyond Doubt. To make out a case of guilt, the State must establish by evidence be- yond a reasonable doubt, fi the death of Charles A. Lindbergh, Ir, as a result of a felonious stroke in- flicted on the first day of March, 1932 at the township of East Amwell in this county. To support that charge the State has produced evidence to the following effect: The fact of death seems to be proved, and admitted. At the time of his death the child was about 20 months old on the evening of March 1, 1932, the child was prepared for bed by its mother and its nurse, Betty Gow, at the Lindbergh home in East Amwell Township in this _county. The evidence is to the effect that the child was then in good health, a nor- mal child except for a slight cold; that the mother and the nurse securely fixed the covering about the child and about 8 o'clock left the room and closed the window: that between that hour and 10 o'clock the child was re- moved from the bed by some person and carriec away, with the clothing in which it had been put to bed, which clothing has been described to you. There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit, that the person who carried away the child entered the nursery or room through the southeast window gment of those act conscientiou jug to of the nursery room, by means of a | ladder placed against the side of the house, under or near the window, and that this occurred shortly after 9 o'clock at night. You will recall col he was sitting in his downstairs, he heard a strange noise about that time, the sound of wood on wood, like the striking of two pieces of wood together, like the boards of a crate falling together off of a stand or chair. Recalls Testimony Of Col. Lindbergn. Col. Lindbergh testified that he could not tell at the time where the sound came from, and at the moment he did not think much about it. Later, at about 10 o'clock, when the dis- appearance of the child became known, a strange and broken ladder was found, about 60 or 70 feet from the southeast window, with indica- tions that it had been used in enter- ing and leaving the window; and also there were the imprints of a man's shoe in the soft ground under or near the window. Miss Gow and Mrs. Whateley testi- fled that later, about April 1, 1932, they found the thumbguard, which Miss Gow had securely tied to the wrist of the child's sleeping suit when she put him to bed, that they found his thumbguard in the road leading from the Lindbergh home and on the Lindbergh property, with the knot still untied, from which you may possibly conclude that the sleeping suit was stripped off of the child at that place. There is also evidence to the effect that there was a dirty smudge on the bed clothes, and also on the floor of the nursery, leading from the window to the child’s crib, and a ransom letter left on the window sill. Later, the child’s dead and decomposed body was found by a colored man in or hard by a shallow grave, not far from the road, a few miles away, in Mercer County. Dr. Mitchell, who performed the autopsy, testified that the child died of a fractured skull, the result of external violence, that the fracture extended from a point about an inch and a half posterior to the left, it extended forward probably three or four inches, it extended upward to one of the fontanels, it extended back- ward around the back of the head; in other words, it was a very extensive fracture. He further testified that, in his opinion, death occurred either in- [ the evidence of child’s bed | Lindbergh to the effect that as | living room | stantaneous or within a very few minutes following the actual fractural occurrence. It is the contention of the State that the fracture described | by Dr. Mitchell was inflicted upon the child when it was seized and carried out of the nursery window down the ladder afld when the ladder broke. Now. the ladder has been placed in evidence. Its broken condition when found in the yard has been described to you. The fact that the child's body was found in Mercer County raises a presumption that the death occurred there; but that, of course, is a rebut- table presumption, and may be over- come by circumstantial evidence. In the present case the State contends that the uncontradicted evidence of Col. Lindbergh and Dr. Mitchell and other evidence, justifies the reasonable inference that the felonius stroke oc- curred in East Amwell Township in Hunterdon County, when the child; was seized and carried out of the. nursery window and down the ladder | Ly the defendant and that death was instantaneous; and from the evl-l dence you may conclude, if you see fit, that the child was feloniously | | stricken on the first day of March |at the township of East Amwell in this county and died as a result of that stroke. | Secondly, the State, in order to jus- tify a verdict of guilty, must estab- lish by the evidence, beyond a rea- sonable doubt, that the death was caused by the act of the defendant. The uncontradicted evidence is that the child was left by the mother and the nurse in the nursery, and the | window was then closed. | | | Ransom Letter Discovery Retold. The evidence justifies the inference, if you see fit to draw it, that the | window was maliciously opened and | | the child seized shortly after 9 o'clock that night. You will, of course, recall the evidence to the effect that almost immediately after it was discovered | that the child had been taken from its crib in the nursery, there was found | the ransom letter, demanding $50,000, {on the window sill, on which was | placed a peculiar symbol and peculiar punch holes, and stating that direc- | tions would later be given for the de- ¢ of the money. There is also | evidence to the effect that a few days ater Col. Lindbergh received a second | | letter with like symbols, referring to | the original ransom letter, and reiter- ating that directions for the delivery | of the ransom money would be given. Meanwhile, Col. Breckinridge, the friend and counselor of Col. Lind- | bergh, had identified himself with the ase in an endeavor to help his friend. | There is evidence to the effect that | a few days before March, 1932, Dr. Condon had inserted an advertisement | | in the Bronx newspaper in effect of- ering to act as a go-between; that a few days later Dr. Condon received | a letter in effect accepting his offer | to act as a go-between and inclosing | & letter to Col. Lindbergh, telling Dr. | Condon that after he got the money to put words in the New York Ameri- can that the money is ready, and the letter to Col. Lindbergh said Condon may act as go-between, to give him the money, with directions as to the package, and how thereafter the baby was to be found. This letter to Col. Lindbergh, as T recall the testimony, contained the peculiar symbols of the original ran- som letter. The evidence is to the effect that immediately Dr. Condon drove to Hopewell and conferred with Col. Lindbergh and with Col. Breck- inridge and, with their acquieseence, he inserted the advertisement, “I ac- cept; money is ready.” Dr. Condon testified that shortly thereafter he received a letter ad- dressed to him, and delivered to him by a taxicab driver, giving him in- | structions how to proceed. The taxi- cab driver testified that he was given | that letter by the defendant, Haupt- | | mann. Dr. Condon testified that, as a | result of the directions contained in | that letter and another letter, he first | | had, on March 12, 1932, an interview |in Woodlawn Cemetery with a man | whom he identifies as the defendant, | after talking with him for more than an hour. In that interview Dr. Con- don said that the defendant, after having run away from the gate, sald, among other things, “it is too danger- ous. Might be 20 years or burn. Would 1 burn if the baby is dead? I am only a go-between.” Flyer Complied With Directions. Dr. Condon also testified in effect that «he defendant said that the baby was being held on a boat by others, { J Here is a portion of the crowd at the Flemington Court House. Jury shown in center bein g escorted from th e building could not have identified that voice, and that it is unlikely that the de- fendant would have talked with Con- don. Well, those questions are for the nination of this jury, after g patiently listened to the evi- e bearing upon those topics. If you find that the defendant was the man to whom the ransom money was delivered, as a result of the directions in the ransom notes, bearing symbols like those on the original ransom note, the question is pertinent: Was not the defendant the man who left the ransom note on the window sill of the nursery and who took the child from its crib, after opening the closed win- dow? It is argued by defendant’s coun- | sel that the kidnaping and murder | was done by a gang, and not by the defendant, and that the defendant was in no wise concerned therein. The argument was to the effect that it was | done by a gang, with the help or | connivance of some one or more servants of the Lindbergh or Morrow households. Now, do you believe that? Is there any evidence in this case whatsoever to support any such conclusion? | | case is, did the defendant Hauptmann write the original ransom note found som notes which followed? Numerous experts testified that the defendant Hauptmann wrote every one of the ransom notes and Mr. Osborn, sr., said that that conclusion was irresistible, unanswerable and overwhelming. On the other hand, the defendant denies that he wrote them and a handwriting expert, called by him, so testified. And so the fact becomes one for your determination. The weight of the evi- dence to prove the genuineness of handwriting is wholly for the jury. As bearing upon the question whether or not the defendant was the man to whom was paid the ransom money in the cemetery, you will of course, consider the evidence to the effect that the defendant had written the address and telephone number of closet; and if you believe that he did, although he now denies it, you may conclude that it throws light upon the question whether or not he was deal- ing with Dr. Condon. As I have said, the defendant denies that he was the man who was paid the ransom money, and there is other | testimony which, if credible and be- lieved by you, supports his statement. You will consider, as bearing upon that question, the fact that a record of the serial numbers of the ransom money was retained. Now, does it not appear that many of the ransom bills were traced to the possession of the defendant? Does it not appear that many thousands of dollars of ransom bills were found in his garage, hidden in the walls or under the floor, that others were found on his person when he was arrested and others passed by that “we are the right parties,” that the baby was held in the crib by safety pins, and he said that he would send the sleeping suit. Dr. Condon | further testified that later he re- ceived the sleeping suit and other letters containing further directions, and finally a letter directing that the money be ready by Saturday night and to put an advertisement in the newspaper, “Everything O. K.” and that these directions were complied | with by him (Condon) with the ac- | quiescence of Col. Lindbergh and Col. | Breckinridge, the latter of whom had been in close ‘ouch with Dr. Condon during practically the whole of the ransom negotiations. There is testimony to the effect that on this Saturday night, April 2, 1932, there was delivered to Dr. Con- don’s residence a letter containing further instructions, and that as a result thereof on that evening Col. Lindbergh, who was there waiting, | drove Dr. Condon to the entrance to St. Raymond’s Cemetery with the ransom money; that Dr. Condon alighted and contacted with a man, and after some talk and some delay handed him the package containing $50,000 of ransom money, $35,000 of which was in gold certificates, the numbers of which bills had been taken It is argued that Dr. Condon’s testimony is inherently improbable and should be in part rejected by you, but you will observe that his testi- mony is corroborated in large part by several witnesses whose credibility has not been impeached in any man- ner whatsoever Of course, if it is in the minds of the jury a reasonable doubt as to the! truth of any testimony, such testi-| mony should be rejected, but, upon the whole, is there any doubt in your mind as to the reliability of Dr. Con- don’s testimony? There is evidence to the effect that after Dr. Condon alighted with the money he was hailed by a man on the other side of the hedge, to whom he finally delivered the ransom money. Col. Lindbergh testified that the voice that hailed Condon was that of the defendant. Dr. Condon testified that the man to whom he delivered the money was the defendant. This 18 denied by the defendant, and there is other testimony bearing upon the matter, and so that question becomes one for your determination. 5 It is argued that Col. Lindbergh him from time to time? No One Testified On Seeing Cash Box. You may also consider in this con- nection the evidence to the effect that shortly after the delivery of the ran- som money the defendant began to purchase stocks in a much larger way and to spend money more freely than he had before. ‘The defendant says that these ran- som bills, moneys, were left with him A very important question in the | on the window sill, and the other ran- | Dr. Condon on the door jamb of his | | { by one PFisch, & man now | you believe that? |” He says that he found them in a | shoe box which had been reposing on | the top shelf of his closet several months after the box had been left with him, and that he then, with- out telling anybody, seeretly hid them, or most of them, in the garage, where they were found by the police. Do you believe his testimony that the money was left with him in a shoe box, and that it rested on the top shelf in his closet for several months? His wife, as I recall it, said that she never saw the box; and I do not | recall that any witness excepting the defendant testified that they ever saw the shoe box there. As bearing upon the question whether or not the defendant was| the man who took the child and left the ransom letter on the window sill, you should, of course, consider the evidence with respect to the ladder, if you find, as seems likely, that it was used in reaching the nursery. That | the ladder was there seems to be un- questioned. If it was not there for the purpose of reaching that nursery | | window, for what purpose was it there? There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit, that the defendant built the ladder, al- though he denies it. Does not the !e\'ldenre'sa!u(y you that at least a part of the wood from which the | ladder was built came out of the floor- | ing of the attic of the defendant? In this connection you should con- | sider the marks upon the wood, and | give the evidence in respect thereto such weight as you think it entitled to, after a consideration of the credi- blity of the witnesses who testified in | respect thereto. The defendant has offered himself as a witness in his own behalf, and the law makes him a competent wit- ness, notwithstanding his very deep | interest in the event of the trial. | Bruno’s Own Story May Be Considered. | His evidence is not to be rejected merely for the reason that he is in- terested, but his interest in the result | may be taken into consideration by you as an important circumstance upon the question of his credibility, the question whether he is telling the truth. You should also consider his testi- mony in view of its inherent prob- ability or improbability, in the light | of all of the facts and circumstances as disclosed by the evidence. It appeared on the examination of | the defendant here in court that he has heretofore been convicted of crime. That testimony may be given consideration by you as affecting his credit as & witness, and for that pur- pose only. The defendant denies that he was ever on the Lindbergh premises, de- nies that he was present at the time that the child was seized and carried away. He testifies that he was in New York at that time. He denies that he received the ran- som money in the cemetery and says that he was at his home at that time on the evening of April 2, 1932. “Should Consider Hochmuth Story.” This mode of meeting a charge of crime is commonly called setting up an alibi. It is not looked upon with any disfavor in the law, for, whatever evi- dead. Do | dence tends to prove that the derend-] ant was elsewhere at the time the| | crime was committed, at the same | time tends to contradict the fact that the crime was committed by the de-| fendant, whereas here, the presence of the defendant is essential to gullt, and if a reasonable doubt of guilt is raised, even by inconclusive evidence | of an alibi, the defendant is entitled to the benefit of that doubt | ®As bearing upon the question of | whether or not the defendant was present at the Lindbergh home on March 1, 1932, you, of course, should consider the testimony of Mr. Hoch- | muth, along with that of other wit- nesses. Mr. Hochmuth lives at or about the entrance of the lane that | goes up to the Lindbergh house. He testified that on the forenoon of that day, March 1, 1932, he saw the defendant at that point, driving rapidly from the direction of Hope- well; that he got in the ditch or dangerously near the ditch, and that he had a ladder in the car, which car was a dirty green This testimony, if true, is highly significant. Do you think that there is any reason upon the whole, to doubt the truth of the old man'’s testi- mony? May he not have well and easily remembered the circumstance, in view of the fact that that very night the child was carried away? Consider Credibility | of Witnesses. The defendant, as I have said, denies that he was there or ever in the neighborhood; but, as bearing upon that question, you should con- sider the testimony of other witnesses, | that the defendant was seen in the | neighborhood not long before March 1, 1932, and give it such weight as | you think it is entitled to, after con- | sidering the credibility of the wit- ‘ nesses, as disclosed by the evidence. The defendant has produced some testimony, besides his own, that he was in New York on the day and eve- | ning of March 1, 1932, and some tes- | timony besides his own, that on the | evening of April 2, 1832, when the ransom money was delivered, he was at his home. This testimony produced by the de- fendant I'shall not attempt to recite in greater detail. It should be given consideration by you and given such weight as you thnk it is entitled to | after considering it in connection with all of the other evidence in the case | bearing upon these questions and al | other questions in the case, determi | nation of which would tend to throw | light upon the case. You should consider the fact, where | it is the fact, that several of the wit- | nesses have been convicted of crime, and to determine whether or not their credibility has been affected thereby; |and where it appears that witnesses Ehave made contradictory statements, | you should consider that fact and de- | thereby. | The evidence produced by the State is largely circumstantial in character. In order to justify the conviction of the defendant upon circumstantial evidence, it is necessary not only that all of the circumstances concur to show that he committed the crime charged, but that they are incon- sistent with any other rational con- clusion. It is not sufficient that the circum- stances proved coincide with, account Where Jury Is Deliberating Copyright, A. P. Wirephoto. Here is the jury room and the table Hauptmana A 2 termine their credibility as affected | for and therefore render probable the hypothesis that is sought to be estab- lished by the prosecution. They mu: exclude to a moral certainty eve other hypothesis, but the single one of guilt, and if they do not do this the jury should find the defendant not guilty. And when the case against the de- fendant is made up wholly of a chain of circumstances and there is rea- sonable doubt as to any fact, the ex- istence of ck essential to estab- lish t ! should be acqui But the crime of murder is not one | which is always committed in the presence of witnesses, and if not so committed, it must be established by | circumstantial evidence or not at all. | And where the essential facts and circumstances are pr ch can- not be explained upon any other theory than that the defendant is e charged against character. If the State has not satisfied you by evidence beyond a reasonable doubt | that the death of the child was caused by the act of the defendant, he must be acquitted. f. on the other hand, the State isfied you beyond a reasonable doubt that the child’s death was caused by the unlawful and criminal act of the defendant while carrying away the child and its cloth- ing, of which unlawful act against| the peace of the State, the probable consequences might be bloodshed, it is murder, and if murder, the degree thereof must then be determined. Explains Statutes On Murder. Now, our statute declares, among other things: Murder, which shall be | committed in perpetrating, or at- | tempting to perpetrate any burglary, | shall be murder in the first degree. | The State contends that the murder in this case was committed in per- petrating a burglary, and is murder | 1n _the first degree. I charge you that if murder was | committed in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree, with- out reference to the question whether | such killing was willful or uninten- tional; and I further charge you, as | requested by the defendant, that in order to convict this defendant you | must be satisfied, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the death of the child | ensued from committing, or attempt- | ing to commit, burglary. at or about the time and place in question. Our statute relating to burglary says: “Any person who shall by night wilfully or maliciously break and enter any dwelling house with intent to steal and commit a battery shall be guilty of a high misdemeanor.” 1f, therefore, the defendant by night wilfully and maliciously broke and en- tered the Lindbergh dwelling house with intent to steal the child and its clothing and to commit a battery on the child, he committed a bur- glary, and if the murder was commit, ted in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree. Evidence on Killing of Child Related. In the circumstances of this case you must be satisfled that the window was shut and that it was raised and opened by the defendant, and that he entered the house. There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit, that the defendant feloniously, wilfully and maliciously broke and entered the dwelling house of Col. Lindbergh in the night time with intent to steal the child and its clothing and commit & battery upon the child; that defendant brought the ladder to the Lindbergh house in East Amwell township, in this county, and placed it up against the house near the nursery window; shortly after 9 o'clock at night he ascended the ladder maliciously and wilfully, opened the closed window and entered the nursery room; that he seized the child and its clothing and carried it out of the nursery room win- dow, and that the fracture of the skull which caused the child’s death was inflicted when the child was seized by the defendant and carried out and down the ladder, and when the ladder broke. If you find that the murder was committed by the defendant in per- petrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree, even though the lkflhnj was unintentional. If there is a reasonable doubt that | the murder was committeed by the defendant in perpetrating a burglary, he must be acquitted. Each Must Reach Own Judgment. I am requested to charge, and do charge, that each juror must reach his own judgment, after discussion of the facts with his fellow jurors. If you find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree, you may, if you see fit, by your verdict, and as a part thereof, recommend imprison- ment at hard labor for life. If you should return a verdict of murder in the first degree and nothing else, the punishment which would be inflicted on that verdict would be death. If you desire to return a verdict of A stealing and ! Defendant’s Wife Hears Bitter Attack by Prosecutor. BY ANNE GORDON SUYDAM. Bpecial Dispatch to The Star. FLEMINGTON, N. J., February 13. —Under the scorching flood released by David Wilentz's tongue, Bruno Rich- ard Hauptmann yesterday took such an avalanche of searing scorn as has seldom beeen poured upon any man of our day and emerged from it as few men could do, unbroken and unbent. It is no longer possible to describe him without repetition, for all points of exaggeration have long since been | passed, and the fittest words by which to create his image are reduced to the skeleton starkness of his frame. He is no whiter than he was Mon- day and for all the days before that. He was as white as any living man could ever be. His face was no more gaunt yesterday as he listened to| murderous denunciation which he will never outlive even should he outlive us all, for already his skin is drawn like parchment across the bleak bones of his skull, which threaten to break through. His eyes can sink no deeper in their sockets, for weeks ago they retreated like hunted animals into the furthermost recesses of their caves. His hands or his lips may twitch, but no longer can you attribute their movement to any conscious impulse. It is as spasmodic, &8 humanly insig- nificant as the reflex of a dead frog's body when salt is poured upon it in the laboratory. Analyzed and Humanized. He has been analyzed and senti- mentalized and humanized, and at the | end of it all you find yourself dis- secting him, a lifeless human specimen | in the laboratory of the world. When | Bruno Richard Hauptmann lies dead, be it soon or be it 50 years ffom now, he will seem more real. He will seem more lifelike, than he did in this court | yesterday. What woman ever heard such| words about her husband as those released by the scornful lash of Wil-| entz' tongue! Hour after hour, as Wilentz stormed upon Hauptmann like a whirlwind of vengeance and stripped him of his last decencies and defenses, | I sat beside this woman and watched | her as the structure of her world fell about her in such shattered frag- | ments as no human hand can ever reassemble. Perhaps her world crashed long ago, who knows, but to- | day the ruins were spread before us {all and whatever her faith in her !man, Anna Hauptmann tasted the full bitterness of public shame. | She seemed more at the point of | | exhaustion than defiance, looked more |as though she might pass out in ]wenrmes than cry out in protest | But, as usual, during court recess, she gathered herself together for an ani- | mated conversation with Hauptmann and for his sake she wore & new hat to court. Tension Cumulative. Any attempt to recreate the impres- | sion left by Wilentz upon us all {would be beyond the ordinary inter- | | pretative power. One would have to ! be here, to have been here for these | |long weeks, to have felt the cumula: | tive tension of this court room as the | air became choked with the fumes of | emotional humanity and the mind crowded to suffocation with the re- lentless pressure of words. Not even the Lindberghs' appearance on the stand, nor Hauptmann fighting for his life in the witness chair, nor Reilly’s resounding plea for Haupt- | mann’s innocence, could touch the lurid heights and depths of those burning words which seethed from the prosecutor’s lips as he branded Bruno Richard Hauptmann “public enemy No. 1 of the world.” As he ended the first half of his summation at the noon recess, this court room, containing hunareds of ordinarily noisy, bound into silence. His defense of Lindbergh's identification of Haupt- | mann’s voice, the quietly convincing | manner with which he spoke of the colonel’s trained senses of sight and hearing, were but a prelude to the | hushed moment when he led us to the cemetery gates with Lindbergh on the night of the ransom payment, and we heard the voice which will ring for- ever in Lindbergh's ears calling “Hey, Doktor! Over here!” How could Lind- bergh forget that voice, cried Wilentz, that voice to which every fiber of his which was to return his baby to the waiting arms of his wife, that voice which he says was Hauptmann's voice, which no one who has ever heard it speak above a whisper could fail to recognize? This was the thirty-first day of this trial, and therefore we have heard 62 times from Justice Trenchard's lips as he adjourned court twice a day the | perfunctory words, “The prisoner is now remanded to the custody of the murder in the first degree, coupled with imprisonment for life, then you must so put it in your verdict, be- cause the law reads that every per- | son convicted of murder in the first degree, its aiders, abettors, counselors and procurers, shall suffer death un- less the jury shall by their verdict | and as a part thereof, upon and after consideration of all the evidence, | recommend imprisonment at hard | labor for life, in which case this and no greater punishment shall be im- posed. The clerk may swear these con- stables to safely keep the jury until they have agreed upon their verdict. | | as scuffling, sneezing | human beings, for once was spell- | being was attuned at this, the great- | est moment of his life, that voice | l\ Hauptmann sheriff,” and have given no more heed to them than to the roll call of the Jury, or any other function of court routine. But as Wilentz ended his breath-taking speech th.s noon, and the morient came for the judge to dismiss Hauptmann, his deep gaze | penetrated the defendant with a sort of profound wonder, as he said in a voice which we have never heard be- fore, “The prisoner,” and here he paused with his eyes still fixed upon him, “is now remanded to the custody of the sheriff.” Almost it was as though he had added “and may God have mercy on his soul.” This was not the mild, impartial, sometimes smiling Trenchard whom we have all grown to know with fond familiarity: this was a man who was probing into another man’s heart; this | was a man who felt upon his bowed shoulders the burden of dreadful re- sponsibility. The very verdict ren- dered by the jury may depend upon the judge’s charge, and he knew it well his still, solemn eyes followed Hauptmann to the door of the library. Troopers Guard Hotel. I think that no one could have left that room in the same mood in which he entered it. Verna Snyder, juror | No. 3, oppressed by the tenseness of the court-room scene, the milling crowds, and no doubt by the sense of responsibility which must weigh upon them all, was unable to finish her lunch in the crowded hotel dining room, where the jury’s only privacy is afforded by a flimsy screen, and retired to her room for a brief rest. She returned to the box white and shaken, and last night troopers were assigned to the second and third floors of the hotel to prevent invasion by the curiosity seekers who thronged Flemington like milling, malicious in- sects. Small wonder if the entire jury was shaken by the cries of the harpies | in the streets as these 12 passed from the court house to the hotel, Hauptmann! Kill Hauptman: Tomorrow they will be locked in a room, which has not yet been des- ignated for fear of dictaphones and other such dishonest devices, and there they will remain in one of the most solemn conclaves ever held over a man. They will not sleep, they will not eat, save by the clemency of Jus- tice Trenchard; they will bare their hearts and minds to each other, who have sat silent so long listening to the words of others, and when they emerge from ‘hat room and file be- fore the judge's bench in their last entrance into this court room, those thousands of words to which they have listened through long weeks will have resolved themselves into ner one or two words, “Guil guilty.” BURNS REFUSES T0 GIVE NAME OF “CONFESSOR” Clergyman, Surprised Over Rumor Implicating Bruno, Says He Wanted to Help Hauptmann. “Kill By the Associated Press FORT LEE, N. J., February 13.— To Rev. Vincent G. Burns his dra- matic outburst during the Hauptmann | trial yesterday was but an episode— he haes resumed life in his peaceful parsonage as if nothing had happened. Fort Lee and neighboring commu- nities are abuzz, however. They heard reports that he would name the man who, he told the court at Flemington had confessed the Lindbergh killing to him. “No,” said Mr. Burns, “I will not make the name public. The man came to my church for protection.” Told that he had been quoted as saying the man resembled Haupt- mann, the clergyman expressed sur- prise. went to Flemington to help Hauptmann,” he said. Lindbergh Case Chronology By the Assoctated Press 1932, March 1—The Lindbergh baby is stolen from Hopewell April 2—Dr. John F. Condon pays the $50,000 ransom to “John” in St. Raymond's Cemetery, the Bronx. May 12—The baby is found, slain, in a thicket grave five miles from the Lindbergh estate. July 2—John Hughes Curtiss, boat builder, convicted of obstructing justice in the case; jury recommended mercy, later pays $1.000 fine. 1933. The search for the kidnapers goes | on, without apparent success. i 1934, September 19 —Bruno Richard is arrested in New York's Bronx; within the week $14,600 in ransom bills are found hidden in his garage. September 26 — Hauptmann is in- dicted for extortion by Bronx County grand jury. October 19—Hauptmann loses his extradition fight and is taken to Flem- ington. 1935. January 2—Hauptmann goes on trial for the baby's murder. February—The verdict? A Bank for the INDIVIDUAL The Morris Plan Bank offers the INDI VIDUAL the facilities of & SAVINGS BANK with the added feature of offering s plan to make loans on a practical basis, which enables the borrower to liquidate his obli- gation by means of weekly, semi- monthly or monthly deposits. $1.200 $6,000 It is wot meces- sary to have had an account at this Bank in order to borrow. Loans are passed within a day er two after filing application—with few exceptions. MORRIS PLAN wotes are usually made for 1 year, though they may be given for any period of from 3 to 12 months. $100 $500 MORRIS PLAN BANK Under Supervision U. S. Treasury 1408 H Street N.W., Washington, D. C. “Character and Earming Power Are the Basis of Credit”