Evening Star Newspaper, January 24, 1932, Page 27

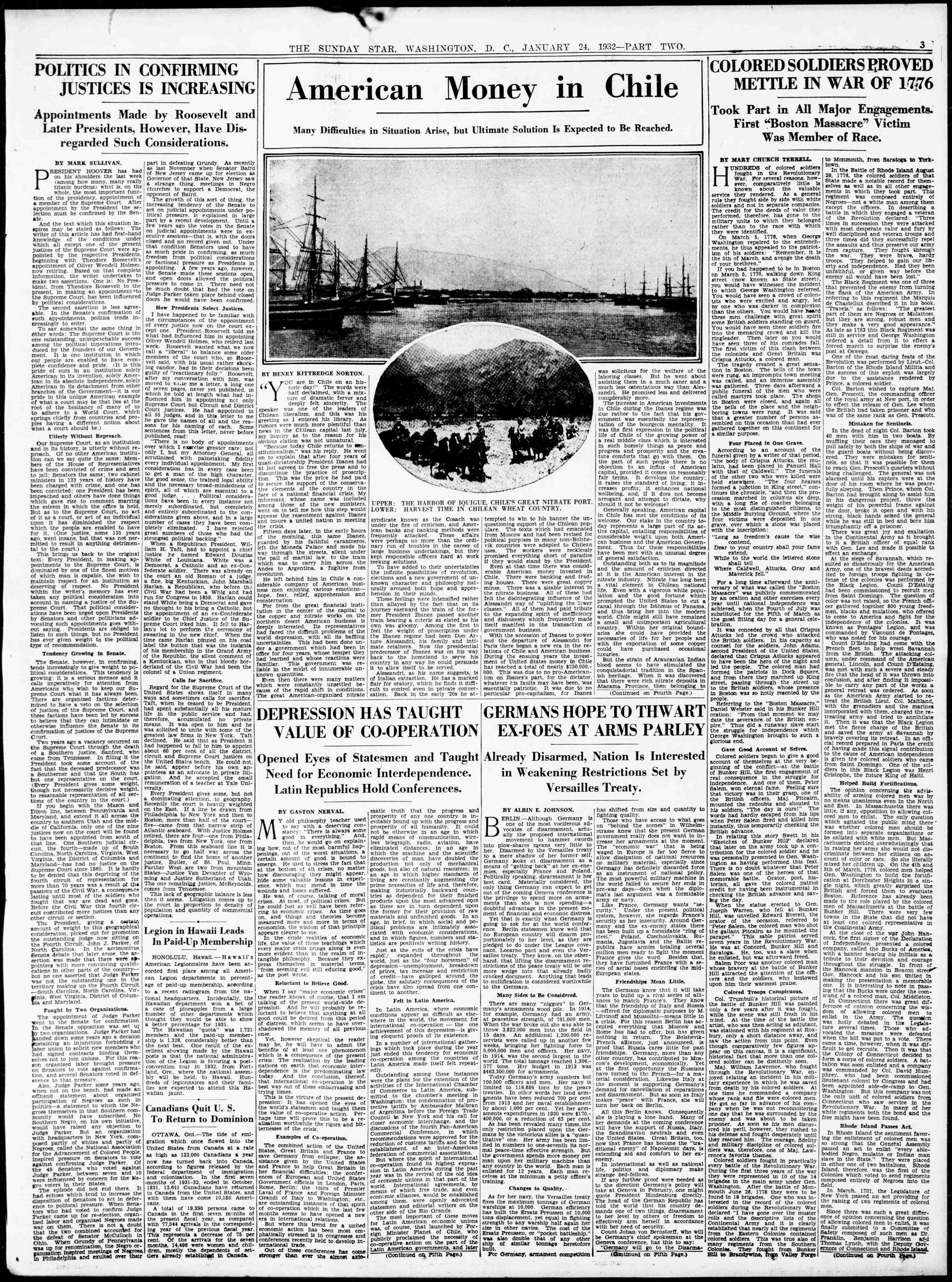

POLITICS IN CONFIRMING JUSTICES 1 S INCREASING Appointments Made by Roosevelt and Later Presidents, However, Have Dis- regarded Such BY MARK SULLIVAN. RESIDENT HOOVER has had on his shoulders the last week | (among how many, many really | titanic burdens) what is, on the whole, the most important func- tion of the presidency, appointment of & member of the Supreme Court. After | appointment by the President the se-| lection must be confirmed by the Sen- ate. And the text which this situation in- spires may be stated as follows: The | writer of this article has had first-hand | knowledge of the conditions under | which all except one of the present Justices of the Supreme Court were ap- inted by the respective Presidents, | &flnnmg with Theodore Roosevelt's | appointment of Oliver Wendell Holmes, | now retiring. Based on that complete | information, the writer undertakes to make two assertions. One is: No Pres- | {dent, from Theodore Roosevelt to the resent, in making an appointment *to he Supreme Court, has been influenced by political considerations. The second assertion is less agree- sble. In the Senate’s confirmation of ruch apjointments, politics tends in- creasingly to enter. To ssy somewhat the same thing in other words: The Supreme Court is the one outstanding. unimpeachable success among the political innovations intro- duced by the founders of our Govern- ment. It is one institution in which | our people are enabled to have com- plete confidence and pride. (It is this pride of ours in an institution solely American in its invention, solely Amer- ican in its absolute independence, solely American in its detachment from other branches of the Government—it is our pride in this unique American example of what a court may be that lies at the root of the hesitancy of many of us to adhere to a World Court, which eprings chiefly from countries and peo- | ples §mmg a different notion about what a court should be.) Utterly Without Reproach. Our Supreme Court, as an institution and in its history, is utterly without re- | proach, Of no other American institu tion can we say quite the same: Mem- bers of the House of Representatives have been convicted of crime and sent to jail; Senators the same; two cab‘xneb; ministers in 133 years of history have been charged with crime, and one has | been convicted; one President has been | impeached and others have done things which gave rise to comment marring the esteem in which the office is held. But as to the Supreme Court, no act of it as a court, or act of an individual upon it has diminished the respect which the people are enabled to have for it. (One justice, some 135 years ago, went insane, but that was not per- mitted to result in anything detrimen- tal to the court.) This brings us back to the original text: Every President, in making ap- pointments to the Supreme Court, is dominated by one of the finest motives of which man is capable, the wish to maintain respect for an institution so deserving of respect. No President within the writer's memory has ever taken any political consideration into account in naming a justice of the Su- preme Court. That political_consider- ations have been urged upon Presidents by Senators and other politicians ad- vocating such _appointments goes with- out saying. Presidents are obliged to listen to such things, but no President has ever given weight to the political type of recommendation. Tendency Growing in Senate, The Senate, however, in confirming, tends increasingly to give weight to po- litical considerations. This tendency is growing; it is a serious menace and it calls imperatively for attention from Americans who wish to keep our Su- preme Court what it has always been. There are organized factions deter- mined to have a veto on the selection of justices of the Supreme Court, and these factions have been led by success to believe that they can intimidate or otherwise influence the Senate in its confirmation of justices of the Supreme Court. Two years ago a vacancy occurred on the Supreme Court through the death of a Southern justice, Sanford, who came from Tennessee. In filling it the President took some account of the fact that the deceased predecessor was a Southerner and that the South has but one representative on the court. (Bvery President gives some weight, though not necessarily decisive weight, to reasonable representation of all sec- tions of the country in the court.) It you begin with the Mason and Dixon line, between Pennsylvania and Maryland, and extend it all across the country to southern Utah and the mid- dle of California, only one of the nine justices now on the court will be found to have been appointed from south of that line. One Southern judicial cir- cuit, the fourth—made up of South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, the District of Columbia and Maryland—has had no justice on the Supreme Court since 1860. It is hardly to be denied that this depriving of the fourth circuit of representation for more than 70 years was a result of the passions of the Civil War, a consequerce Jasting until most of the soldiers who fought that war are dead and gone. Before the Civil War this fourth cir- cuit contributed mor)e justices than any other circuit or section. Ths President, giving & cestain amount of weight to this geographical | consideration, picked out for promotion | the outstanding judge now sitting on the Fourth Circuit, John J. Parker, of North Carolina. In the acrimonicus Senate debate that later arose, the as- sertion was made that there were ap. pointees with more convincing qualifi- cations In other parts of the country— but no one asserted that Judge Parker was not the outstanding one in the territory making up the Fourth Circuit —South Carolina, North Carolina, Vir- | nia, West Virginia, District of Colum- | ia and Maryland Fought by Two Organizations. The appointment of Judge Parker went to the Senate for confirmation In the Senate opposition was set uj y two organizations. Judge Parker had nded down some years ago & decision pustaining an injunction forbidding r Jabor union to solicit new members who had signed contracts binding them- selves not to join unions. For this rea- son organized labor brought pressure on Senators to vote against confirma- tion, and several Senators voted in def- erence to that pressure Also, Judge Parker some years &go, when not on the bench, had made an offhand statement about organized participation of Negroes as such in politics—a statement to which the Ne- groes themselves in that Southern com- munity would have subscribed. No Southern Negro, on his own initiative, would have raised any objection to Judge Parker. But an organization with headquarters in New York, com- posed partly of whites and partly of Negroes, called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, inspired pressure on Senators to vote against confirming Judge Parker. Of the 49 Senators who voted against Judge Parker, between seven and 10 ‘were Lnfluencedhby Cg{\:‘;m for the Ne- voters their s, e episg;e did not end there. It had echoes which tend to increase the disposition of Senators to act in defer- ence to political pressure. When Sena- tors who had voted to confirm Judge swearing in the new chief. time came Harlan pinned on his coat label the button that was the insignia of his membership in the Grand Army of the Republic, the silent comment of a Kentuckian, who in that bloody bor- derland of the Civil War had been the colonel of a Union regiment. Considerations. part in defeating Grundy. As recently as last November when Senator Baird of New Jersey came up for election as Governor of that State, New Jersey saw a strange thing, meetings in Negro churches to support a Democrat, the opponent of Baird, The growth of this sort of thing, the increasing tendency of the Senate to act on judicial appointments under po- litical pressure, is explained in large part by a recent development. Until & few years ago the votes in the Senate on judicial appointments were in ex- ecutive sessfons—that is, with the doors closed and no record given out. Under that condition Senators used to have as much pride in confirming, as much freedom from political considerations or factional pressure as Presidents in appointing. A few years ago, however, the Senate made these sessions open, and open doors allowed the political pressure to come in. There need not be much doubt that had the vote on Judge Parker taken place behind closed doors he would have been confirmed. How Presidents Select Justices. I have happened to be familiar with the circumstances of the appointment of every justice now on the court ex- cept one. President Roosevelt told me what had influenced him in appointing Oliver Wendell Holmes, who retired last week. Roosevelt wanted what we now call a “liberal” to balance some older members of the court who, so Roose- velt said, with his usual rather shock- ing candor, had in their decisions been guilty of “reactionary folly.” Roosevelt, after my conversation with him, was moved to Wi.te me a letter, a long one of seven pages, never yet published, in which he told at length what had in- fluenced him in appointing nct only Supreme Court but Circuit and District Court justices. He had appointed in all 55 judges, and in this letter to me he gave the names of all and the rea- flie for }11Ls nt}r:-xmlnlg of each. Some nces from etter, nev pub’lll:ks]hed. lreld: ever before “There is no body of appointments over which I exarcise grencgl? care; not only I, but my Attorney General, all scrutinized with painstaking fidelity every indtvidual appointment. My first consideration has in every case been to get a man of the high character, the good sense, the trained legal ability and the necessary broad-mindedness of spirit, all of which are essential to a good judge. Political considera- tions have been in every instance not merely subordinated, but completely and entirely subordinated to the con- siderations given above, and in a large number of cases they have been com- pletely eliminated. I have rejected great numbers of those who had the strongest political backing.” When a Republican President, Wil- |liam H. Taft, had to appoint a chief justice re named Edward Douglas White of Louisiana. White was a Democrat, a Catholic and an ex-Con- federate soldier. There was already on the court an old Roman of a judge, a fine, big Kentuckian, John Marshall Harlan, a Republican, who before th: Civil War had been a Whig and had run for Congress in 1859. Harlan could stand White being a Democrat and gave no thought to his being a Catholic, but the appointment of an ex-Confederate soldler to be Chief Justice of the Su- preme Court irked him. It fell to Har- lan's lot to perform tbe ceremony of When the i Calls for Sacrifice. Regard for the Supreme Court of the United States shows itself in many ways and sometimes calls for sacrifice. Taft, when he ceased to be President, had spent substantially all his mature life in the public service and had, therefore, accumulated no private means. It was open to him and he was solicited to unite with some of the greatest law firms in New York. Taft declined. He said that as President it had happened to fall to him to appoint about 60 per cent of all the district, circuit and Supreme Court justices on the United States bench. He could not, he said, appear before his own ap- pointees as an advocate in private liti- gation. And he accepted the small remuneration of a teacher at Yale Uni- versity. Every President gives some, but not a dominating attention, to geography. Recently the court is heavily weighted on the East. If a line be drawn from Philadelphia to New York and then to Boston, more than half of the court— five—came from that narrcw strip of Atlantic seaboard. With Justice Holmes retired, there are four—one from Phila- delphia, two from New York, one from Boston. From this seaboard line it is necessary to go half way across the continent to find the home of another justice, Butler, of St. Paul, Minn. Farther West are two from mountain States—Justice Van Devanter of Wyo- ming and Justice Sutherland of Utah. The one remainigg justice, McReynolds, comes from Termessee. ‘This lack of geographic balance is less then it seems. Litigation comes up to the court in proportion to density of population and quantity of commercial operations. Legion in Hawaii Leads In Paid-Up Membership HONOLULU, Hawali —Hawalil's American Legionnaires have been ac- corded first place among all Ameri- tional headquarters. Hawallan _department won a bet of & case of pineapples from a large number of other departments which thought they would be able to show a better percentage for 1931. The Hawallan “quota” was 1,721 members and the paid-up member- ship is 1,328, considerably better than the next best. One result of the ex- cellent showing made by the Hawaii posts is that the national administra- tion of the Legion is favoring & post- convention tour in 1932, from Port- land, Ore.. where the national assem- bly ‘'will be held, to Hawaii. Hun- dreds of legionnaires and their fami- lies are expected to attend this Ha- wallan jaunt. Canadiians Quit U 8. To Return to Dominion Incidentally, the OTTAWA, Ont.—The tide of emi- gration which once flowed into the United States from Canada at a rate as high as 122,000 Canadians a year now has turned back into Canada, according to figures released by the federal department of immigration and colonization. In the first seven smonths of 1931-32, ended in October, 1931, 13,641 Canadians have returned to Canada from the United States, and with them have come 10,186 Ameri- cans. A total of 19,390 persons came to r came up for re-election, organ- mkilbor and pm—nnlmsd Negroes made war on them, There is not doubt that the two combined accoun! for Canada in the first seven mcnths of the present fiscal year, as compared with 77,544 agrivals in the correspond- ing year of the previous fiscal year. of Senator McCulloch in|This represents a decrease of 75 per hio. When G 3.. up for renominati N grrmation Inspirel Tnerulied over rundy of Pennsylvania | cent. Of the arrivals for the seven months, 14,496 were women and chil- dren, mostly the dependents of set- tlers already established in Canads. can Legion departments in percent- | age of paid-up membership, aceording to a recent radiogram from the na-' BY HENRY KITTREDGE NORTON. OU are in Chile on an his- ¢ toric day!” The words were half declaimed, with a mix- ture of dramatic fervor and deeply felt sincerity. The speaker was one of the leaders of Chilean liberalism, and this was his greeting as I entered his library. As rumors were much more plentiful than news in the Chilean capital last july, my inquiry as to the reason for his obvious elation was not unnatural. “Because today Chile returns to een- stitutionalism,” was his reply. He went on to explain that after four years of quasi-dictatorship President Ibanez had at last agreed to free the press and to discontinue the practice of proscrip- tion. This was the price he had paid to secure the support of the conserva- tive elements of the country in the face of a national financial crisis. My informant, whose name was included among those of the new ministers, went on to tell me how this step would appease the resentment against Ibanez and insure a united nation in meeting the crisis. Fifteen days later, in the early hours of the morning, this same Ibanez, puarded by his faithful carabineros, left the Moneda Palace and made his way through the streets, silent under the pall of martial law, to the train which was to carry him across the Andes to Argentina, a fugitive from revolution. He left behind him in Chile a con- siderable company of American busi- ness men enjoying various emotions— hope, fear, relief, apprehension and consternation. For from the great financial insti- tution in the center of the capital to the copper and nitrate works on the northern desert American business is deeply interested. Its representatives had faced the difficult problems of the world depression, with all its baffling uncertainties. This had been done un- der a government which had been in office for four years, whose temper they had learned and whose reactions were familiar. This government was re- liable in the midst of innumerable un- known quantities. Even then there were many matters which were constantly unsettled be-| cause of the rapid shift in conditions. The great American-organized nitrate | | UPPER: LOWER: syndicate known as the Cosach was under the fire of criticism, and Amer- ican banks and banking methods were | frequently attacked These affairs were perhaps no more than the ordi- large business undertakings, but they kept responsible officers hard at work seeking solutions. ‘To have added to their uncertainties the infinite possibilities of revolution, elections and a new government of un- known character and philosopby nat- urally aroused both hope and appre- hension in their minds. than allayed by the fact that on fits journey eastward the train of the for- mer President Ibanez passed another train bearing a ccterie as elated as his own was gloomy. Among the first to feel the weight of proscription under the Ibanez regime had been Don Ar- turo Alessandri, his family and inti- mate retainers. Now the presidential predecessor of Ibanez was on his way back to the homeland to serve his country in any way he could persuade it to allow itself to be served. Alessandri, as his name suggests, is of Italian extraction. He has a marked flair for oratory, which he finds it diffi- cult to control even in private conver- sation. Back in the early '20s he at- nary run of troubles in the career of | These feelings were intensified rather | g P e THE HARBOR OF IQUIGUE, CHILE'S GREAT NITRATE PORT. HARVEST TIME IN CHILEAN WHEAT COUNTRY. tempted to win to his banner the un- questioning support of the Chilean pop- ulace. The texts which had emanated from Moscow and had been revised for political purposes in many non-Bolshe- vik countries were adapted to Chilean uses. The workers were recklessly promised everything short of paradise if they would stand by the President. Even at that time there was consid- erable American money invested in Chile. There were banking and trad- ing houses. There were great copper mines. There was a sizable interest in the nitrate business. All of these had felt the disintegrating influence of the Alessandri way of “uplifting the lower classes.” All of them had paid tribute to the expanding spirit of inefficiency and dishonesty which frequently made itself manifest in the transaction of government business. ‘With the accession of Ibanez to power and the departure of Alessandri for Paris there began a new era in the re- lations of Chile and American business. During the ensuing years the invest- ment of United States money in Chile has reached a total of nearly $750,000,- 000. This was due to no pro-American- ism on Ibanez's part, for the dictator, whatever his faults may have been, was essentially patriotic. It was due to no particular pro-capitalism, for Ibanez American Money in Chile Many Difficulties in Situation Arise, but Ultimate Solution Is Expected to Be Reached. was solicitous for the welfare of the laboring classes. But he went about assisting them in a much saner and a much less ostentatious way than Ales- sandri. He promised less and delivered congyderably more. ‘The increase in American investments in Chile during the Ibanez regime was due rather to the fact that his gov- ernment was essentially the represen- "Lfltlon of the bourgeois mentality. It was the first expression in the political life of Chile of the growing power of a real middle class which is interested in such homely things as peace and progress and prosperity and the crea- ture comforts that go with them. On the part of such people there is no objection to an influx of American capital, provided i{ comes on reasonably fair terms. It develops the country; it raises the standard of living; it in- creases profits; it enhances national wellbeing, and, if it does not become | arrogant and attempt to dictate, why | should it not be welcome? Generally speaking, American capital in Chile has met the conditions of its welcome. Our stake in the country to- day represents a large part of its ac- tive capital, entailing responsibilities of considerable weight upon both Ameri- can business and the American Govern- [ment. Thus far these responsibilities | have been met with an unusual degree of general satisfaction. Outstanding both as to its magnitude and the amount of criticism directed at it is the American interest in the nitrate industry. Nitrate bas long been a vital element in Chilean national life. Even with a vigorous white popu- lation and the good fortune which prompted the United States to cut a canal through the Isthmus of Panama, and thus bring her into the modern world, Chile might still have remained a small and unimportant agricultural country. Within her original bound- aries she could have provided the necessaries of life for her people and with the exportation of some copper could have purchased occasional luxuries. But the strain of Araucanian Indian blood seems to have stimulated the conquistadorial tradition in the Span- ish heritage. When it was discovered | that there were rich nitrate deposits in | Atacama Province, then belonging to (Continued on Fourth Page.) BY GASTON NERVAL. Y old philosophy teacher used to say with a deserving con- stancy: “There is always some good in everything.” And, then, he would go on explain- ing how, out of the most harmful hap- penings, out of the worst situations, & certain amount of good is bound to emerge. He used to stress the fact that at the bottom of all crises, no matter how discouraging they might appear, hide some valuable lessons in experi- ence, which may mend in time the wounds and losses suffered. He was, of course, talking of moral crises. At most, of political crises. But he could just as well have been refer- ring to economic crises. As time goes on, and things and theories become measured more and more in terms of economics, the wisdom of that principle appears clearer to me. In the crude realities of economic life, the value of those teachings which every major crisis brings along is even more_evident than in the realm of in- tangible philosophy. Because they ex- press themselves in material terms, “from seeming evil still educing good,” as the poet wrote. Reluctant to Believe Good. When T say “major economic crises” the reader knows, of course, that I am talking of the present world-wide de- pression. And he will probably be re- luctant to believe that anything at all good could be derived from this period of distress, which seems to have over- shadowed the memory of all previous ones. Yet, however skeptical the reader may be, he will have to admit the benefits of at least one phenomenon which is & consequence of the present crisis: The realization by the leading nations on earth that economic inter- dependence is the predominating law today. And the conclusion, thereof, that international co-operation is the best way out of these embarrassing and trying times. This is the virture of the present de- pression: It has opened the eyes of the world's statesmen and taught them the value of co-operative action. Per- haps time will prove this to be a re- alization worthwhile the rigors and bit- ternesses of the crisis, Examples of Co-operation. The combined action of States, Great Britain and m’:nr(\{;;“e'g save Germany from collapse; the as- sistance given by the United States and France to help Great Britain in her financial difficulties; the confer- ences of European and United States Government offici2ls in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin: the visits of Premier Laval of France and Foreign Minister Grandi of Italy to Washington; ete., are outstanding instances of that spirit of co-operation which in the last few months seems to have opened a new era in international relations, But where this trend for a united economic action has been most em- phatically stressed is in congresses and conferences recently held to develop in- mou.z.h';‘l trade. of these conferences has come stronger than ever the almost axio- DEPRESSION HAS TAUGHT VALUE OF CO-OPERATION Opened Eyes of Statesmen and Taught Need for Economic Interdependence. Latin Republics Hold Conferences. matic truth that the progress and prosperity of any one country is in- evitably bound up with the progress and prosperity of all humanity. It could not be otherwise in an age in which rapld means of communication, Wire- less telegraph, radio, aviation, have eliminated distances; in an age in which the machine and the scientific discoveries of man have doubled the production not only of mechanical goods, but also of natural resources; in an age in which higher standards of living are constantly augmenting the prime necessities of life and, therefore, making industrially backward coun- tries as dependent for their finished products upon the most advanced opes as these are in turn dependent upon the former for their provision of raw materials and unfinished goods. In an age, in brief, in which social and po- litical probléms are intimately asso- ciated with economic considerations, and in which figures, numbers and sta- tistics are positively writing history. Just as the evils of the crisis have rapidl; expanded _throughout the world, just as the “four horsemen” of depression—unemployment, breakdown of prices, tax increase and restriction of credit—have galloped around the globe, the salutary consequences of the crisis have also spread from one con- tinent to another. Felt in Latin America. In Latin America, where economic conditions appear as difficult as else- where in the world, the movement for international co-operation — the one achievement of this depression—is giv- ing eloguent proofs of its existence. In a number of international gather- ings which took place during the year just ended this tendency for economic co-operation among the countries of Latin America made itself felt repeat- dly. § gummndlng among these instances were the plans for the extension of the activities of the International Chamber of Commerce to Latin America, sub- mitted to the chamber'’s meeting in ‘Washington; the condemnation of pro- tective tarifis by Ambassador Malbran of Argentina before the Foreign Trade Council #n New York and his call for closer economic interchange, and the discussicns of the fourth Pan-American Commercial Conference, in which recommendations were approved for the reduction of customs tariffs and for the establishment of an inter-American federation of commercial assoclations. But where the spirit of internaticnal co-operation found its highest expres- Slon in Latin America during the past year was in the revival of the old idea of economic unions in that part of the world. International agreements, by means of which free trade, and even econcmic alliances, would be established among them, were openly advocated Statesmen and editorial writers on the Sther side of the Rio Grande. ‘The most important of tnese moves for Latin American eccnomic unions was, of course, that launched by For- elgn Minister Planet of Chile, who Dublicly proclaimed the necessity of co-operative action on the part of the Latin American governments, and later (Continued on, Fifth Page.) GERMANS HOPE TO THWART EX-FOES AT ARMS PARLEY Already Disarmed, Nation Is Interested in Weakening Restrictions Set by Versailles Treaty. BY ALBIN E. JOHNSON. ERLIN.—Although Germany is one of the most vociferous ad- vocates of disarmament, actu- ally the proposed international movement to hammer swords into plow-shares means very little to her. Disarmed by the Versailles treaty to a mere shadow of her former self, Germany Jooks at disarmament as a means of “getting back” at her ex-ene- mies, especlally France and Poland. Politically speaking, disarmament is her best card. Materially considered, the only thing Germany can expect to get out of the coming Geneva conference is the privilege to spend more on arma- ments than she is now spending—a doubtful advantage in the present mo- ment of financial and economic distress. Yet that is exactly what Germany is going to ask for at the world confer- ence. Berlin statesmen know well that no European country will disarm pro- portionately to her level, as they are pledged to do under the League cove- nant, Locarno pact and even the Ver- sailles treaty. They know, on the other- hand, that lifting the disarmament re- strictions of the peace treaty will be one more wedge into that already badly cracked document. Anything that leads to nullification is considered worthwhile to the Germans. Many Sides to Be Considered. There are many “niggers” in Ger- many’s armaments wood pile. In 1914, for example, Germany had an army, at peacetime strength, of 791,000 men. When the war broke out she was able to throw 3,822,000 men into the field in 15 days. An additional 1,200,000 re- servists were called up in another few weeks, bringing her fighting force to 5,000,000 men and officers. Her navy, in 1914, was the second largest in the world. The total tonnage reached 1,306,- 577 tons. Her budget in 1913 was $463,300,000 for armaments. Today Germany’s army numbers but 100,500 officers and men. Her navy is limited to 116,886 tons by the peace treaties. In othsr words her land arm- ents have been reduced 700 per cent rom 1913 and her naval establishment by about 1,000 per cent. Yet her arm- aments expenditures in 1930 were $170, 400,000, or a reduction of 63 per cent. As has been revealed many times, the only restriction placed upon the Ger- mans by the victorious allies is a “quan- titative” one. Her army has been lim- ited in numbers to one-seventh its nor- mal peace-time effective strength. But the government spends more money per man upon her military machine than any country in the world. Each man Is enlisted for 12 years. Each man re- celves at the minimum a petty officer’s training. Changes to Quality. As for her navy, the Versallles treaty fixes the maximum tonnage of German warships at 10,000. German efficiency has bullt the Ersatz Preussen of 10,000 tons displacement, yet equal in fighting strength to any warship half again her size in other navies. The cost of the Ersatz Preussen, or “pocket battleship,” was also double that of any other ;hl & of tonnage heretofore ul For Germany, armament competition has shifted from size and quantity to fighting quality. | Those who have access to what goes on “behind the scenes” in Wilhelm- strasse know that the present German | government really does not want to in- crease her armaments at the moment. The “economic war” that is being waged in Europe is far too flerce to | allow dissipation of national resources |on military material, especially since | Germany has definitely discarded force as an instrument of national policy. The most powerful military machine in the world failed to secure her ends in pre-war days—days when the diplo- mat’s last argument was a formidable army or navy. Like France, Germany wants ‘se- curity.” Under the present political system, however, she regards France's security as her insecurity. Around Ger- many and the ex-enemy states there has been built up a formidable “ring of steel.” Poland, Czechoslovakia, Ru- mania, Jugoslavia and the Baltic re- publics have armies totaling several million men ready to fight the moment France gives the word. Besides that, they have furnished France with a se- ries of aerial bases encircling the mid- European states. Friendships Mean Little, The Germans know that it will take years to build up a rival series of alli- ances to match France's. They know | that the friendship of Italy and Russia | —offered for diplomatic purposes by M. | Litvinoff and Mussolini—means little in | & crisis. For this reason Berlin has ac- | cepted ~ everything that Moscow and Rome has had to offer, but has given | nothing in return. The Bolshevik- French alliance, just announced, is | proof that Russia cares little for past | friendships. Germany, more than any other country, has contributed to Mos- | cow's development, economically. ~Yet at the first opportunity the Russians have turned to the French—for a ma- | terial consideration. Likewise Italy at | the moment is supporting Germany's | demand for cancellation of reparations | and disarmament. But as soon as Italy makes ‘“peace” with France, she will turn her back on Berlin. All this Berlin knows. Consequently she is playing a lone hand. Many of her demands at the coming conference will have the support of Russia, Italy, the Scandinavian neutrals and even the United States. Great Britain, too, now that France has become the “tra- ditional enemy” of Napoleonic days, is extending aid and comfort to her ex- enemy. In international as well as national life, politics and diplomacy make strange bed-fellows. If any further proof were needed as to the direction Germany's policy will take at Geneva in February, one might quote President Hindenburg directly. The head of the German Republic has told the world that his country de- mands one of two things, disarmament, to her level by others or freedom to effectively arm herself in accordance with her need of security. Count Johan von Bernstorff, who will be Germany's chief spokesman at the Geneva conference, has this to say: & y will go to the Disarma- tinued on Fifth Page) « METTLE IN THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C., JANUARY 24 1932—PART TWO. - " TR - 0, Ico LORED SOLDIERS PROVED WAR OF 1776 Took Part in All Major Engagements. First “Boston Massacre” Victim Was Member of Race. BY MARY CHURCH TERRELL UNDREDS of colored soldiers fought in the Revolutionary War. For several reasons, how- ever, comparatively little is known about the valuable service they rendered. As a general rule they fought side by side with white soldiers and not in separate companies. The credit for the deeds of valor they performed, therefore, has gone to the military units to which they belonged rather than to the race with which' they were identified. | On March 5, 1776, when George Washington repaired to the entrench- ments, he thus appealed to the patriot- ism of his soldiers: “Remember, it is| the 5th of March, and avenge the death of your brethren.” Tt you had happened to be in Boston | on March 5, 1770, walking down King | street (now known as State street), | vou would have witnessed the incident to which George Washington referred. You would have seen a crowd of colon- 1sts who were excited and angry, led by one who was darker in complexion than the others. You would have heard these men challenge with great spirit some British soldlers standing on guard. You would have seen these soldiers fire into the menacing crowd and kill the | ringleader. Then later on you would have seen three of his comrades fall. The first victim of this clash between the colonists and Great Britain was Crispus Attucks, a colored man. The tragedy created a great sensa- tion in Boston. The bells of the town were rung, an impromptu town meeting was called, and an immense assembly was gathered. Three days afterward a public funeral of the men who were called martyrs took place. The shops in Boston were closed, and again all the bells of the place and the neigh- boring towns were rung. It was sald that a greater number of persons as- sembled on this occasion than had ever gathered together on this continent for a similar purpose. Four Placed in One Grave. According to an account of the funeral given by a writer of that period, “the body of Crispus Attucks, the mu- latto, had been placed in Fanueil Hall with that of Caldwell” The funerals held elsew! “The four hearses formed & junction in King street,” con- tinues the chronicle, “and then the pro- cession marched in columns six deep, with a long file of coaches belonging to the most distinguished citizens, to the Middle Burying Ground, where the four victims were deposited in one with the inscription: “Long as freedom’s cause the wise | contend, | Dear to your country shall your fame extend, While to the world the lettered stone shall tell ‘Where Caldwell, Maverick fel For a long time afterward the anni- versary of what was called the “Boston Massacre” was publicly commemorated | by an oration and other exercises every year until national independence was achieved, when the Fourth of July was substituted for the Fifth of March as the most fitting day for a general cele- bration. It was conceded by all that Crispus Attucks led the crowd who attacked the British soldiers. In his capacity as counsel for the soldiers, John Adams, second President of the United States, declared that Crispus Attucks appeared to have been the hero of the night and led the people. The colored man had formed the patriots in Dock Square, and from there they marched up King street, passing through the street up' to the British soldiers, whose presence in Boston was so hotly resented by the people. Referring to the “Boston Massacre,” Daniel Webster said in his Bunker Hill | oration: “From that moment we may | date the severance of the British em- pire.” Thus did a runaway slave start the struggle for independence which George Washington brought to such a Attucks, Gray and glorious end. Gave Good Account of Selves. Colored soldiers began to give a good account of themselves at the very be- ginning of the conflict—at the battle of Bunker Hill, the first engagement of real consequence in the struggle for independence. And one of them, Peter Salem, won eternal fame. Feeling sure that victory was in their grasp, one of the British officers, Maj. Pitcairn, mounted the redoubts and shouted to his soldiers, “The day is ours!” The words had hardly escaped from his lips when Peter Salem fired and killed him instantly, thus temporarily checking the British advance. In relating this story Swett in his «Sketches of Bunker HIill" declared that later on the army took up a con- | tribution for the colored soldier and he was personally presented to Gen. ‘Wash- ington as having performed this feat. There is no doubt whatever that Peter Salem was one of the heroes of that memorable battle. Orator, poet, his- torlan, all gave the colored patriot credit for having been instrumental in checking the British advance and sav- ing the day. ‘When the statue erected to Gen. Joseph Warren, who fell at Bunker Hill, was unveiled Edward Everett, the orator of the occasion, referred to “Peter Salem, the colored man who shot the gallant Pitcairn as he mounted the parapet.” ‘This sable patriot served seven years in the Revolutionary War. He was at Concord, Bunker Hill and Saratoga. He, too, was & slave when he enlisted, but was afterward freed. Salem Poor was another colored man whose bravery at the battle of Bunker Hill attracted the gttention of the offl- cers and the soldiers, who bestowed upon him their warmest praise. Colored Troops Conspicuous. Col. Trumbull's historical picture of the battle of Bunker Hill was painted only a few years after it was fought, while the scene was still fresh in his mind. At the time of the battle the artist, who was then acting as adjutant, was stationed with his regiment at Rox- bury, only a short distance away, and saw the action from this point. Even though comparatively few figures ap- ear on this canvas, it is a significant, istorical fact that more than one col- ored soldier can be distinctly seen. Maj. William Lawrence, who fought through the Revolutionary War, en- joyed relating an incident in his mili- tary experience in which he was saved from death by his colored soldiers. At one time he commanded a company whose rank and file were colored men. He got so far in advance of his com- pany when he was out reconnoitering one day that he was surrounded by the enemy and was about to be taken prisoner. As soon as his men discov- ered his peril, however, they rushed to his defense and fought desperately until they rescued him. The courage, fidelity and military discipline of colored sol- diers was, therefore, one of Maj. Law- rence’s favorite themes. Colored soldlers fought in practically every battle of the Revolutionary War. During the first three years of the war they were represented in 10 of the 14 brigades in the main army under Gen. ‘Washington. After the battle of Mon- mouth June 28, 1778 they were to be found in 18 brigades. One who was in- terested in the record of the colored soldiers during the Revolutionary War declared “I have gone over the muster rolls and the descriptive lists of the Continental Army and it is clearly established that nearly all the regiments from the Eastern Colonies contained colored soldiers. is was true also of many regiments from the Southern of the other two who were killed were | grave, over which a stone was placed | to Monmouth, from Sara to York- th, toga In the Battle of Rhode Island At 20, 1778, the colored soldiers of it State made a notable record for them- selves as well as in all other engage- ments in which they took part. This regiment was composed entirely of Negroes—not a white man among them except the officers. In describing a battle in which they engaged a veteran of the Revolution declared: ‘“Three times in succession they were attacked with most desperate valor and fury by well disciplined and veteran troups and three times did they successfully repel the assaults and thus preserve our army from capture. They fought through the war. They were brave, hardy troops. They helped to gain our lib- erty and independence. Had they been unfaithful, or given way before the enemy all would have been lost.” The Black Regiment was one of three that prevented the enemy from turning the flank of the American Army. In referring to this regiment the Marquis de Chastellux described it in his book, “Travels,” as follows: “The greatest part of them are Negroes or Mulattoes, but they are strong, robust men and they make a very good appearance.” As late as 1783 this Black Regiment was still in service and George Washington ordered a detail from it to effect a forced march to surprise the enemy's | post at Oswego. One of the most daring feats of the Revolution was performed by Lieut.-Col. Barton of the Rhode Island Militia and | the success of this exploit was largely |due to the assistance rendered by Prince, a colored soldier. Col. Barton wished to capture Maj. Gen. Prescott, the commanding officer of the royal army at New port, in order to effect the release of Gen. Lee whom the British had taken prisoner and who | was of the same rank as Gen. Prescott. Mistaken for Sentinels. In the dead of night Col. Barton took 40 men with him in two boats. By muffling their oars they managed to pull safely by both the ships of war and the guard boats without being discov- ered. They were mistaken for senti- nels, so that it was possible for them | to reach Gen. Prescott’s quarters without being challenged. The general was not alarmed until his captors were at the door of his room where he was peace- | fully sleeping. Then Prince, whom Col. Barton had brought along to assist him in his dangerous project, threw the | weight of his powerful frame against | the door, broke it open and with his strong, black hands seized the general while he was still in bed and bore him triumphantly off a prisoner. There was great joy and exaltation In the Continental Army as it brought to it a British officer of equal rank with Gen. Lee and made it possible to effect an exchange. At the siege of Savannah, which re- | sulted so disastrously for the American Army, one of the bravest deeds accred- ited to foreign troops fighting in de= fense of the colonies was performed by the Black Legion. Count D'Estaing | had been commissioned to recruit men from Saint Domingo. The question of color was not raised, =o the French offi- cer gathered together 800 young freed- men, blacks ahd mulattoes, who offered to come to America and fight for the independence of the colonies. It was known as Fontages’ Legion, and was commanded by Viscount de Fontages, who was noted for his courage. Count D'Estaing had come with the PFrench fleet to help wrest Savannah from the British. The attacking col- umn, under command of the American general, Lincoln, and Count D'Estaing, was met with such a severe and steady fire that the head of it was thrown into confusion, and after finding it impossi- ble to carry any part of the works a general retreat was ordered. As soon as the American Army started to re- treat the British Lieut. Col. Maitland, with the grenadiers and the marines incorporated with them, charged the re- treating army and tried to annihilate it. Then it was that the Black Legion met the fierce charge of the British and saved the army at Savannah by bravely covering its retreat. In an offi- cial record prepared in Paris the credit of having made this signal contribution to the cause of American independence is given the colored soldiers who came from Saint Domingo. One of the sol- diers in this Black Legion was Henri Cristophe, the future King of Haiti. Helped Build Fortifications. The opihion concerning the advis- ability of arming colored men was by no means unanimous even in the North and East. In Massachusetts there was little, if any, opposition to allowing col- ored men to enlist. The only question which agitated the public mind there * was whether colored men should be formed into separate organizations or be enlisted with white men. But Mas- sachusetts decided overwhelmingly that in raising her army she would not dis- criminate between her citizens on ace count of color or race. So she literally mixed her children up. On the 4th and 5th of March, 1776, colored men helped Gen. Washington to build the fortifi- cation at Dorchester Heights in a sin- gle night, which greatly surprised the British and forced them to evacuate Boston. Reference has already been made to the role played by the colored men of Massachusetts at the battle of Bunker Hill. There were very few towns in the State that did not have at least one colored representative in the Continental Army. At the close of the war John Han- cock, the first signer of the Declaration of Independence, presented a colored company, called the Bucks of America, with a banner bearing his initlals as a tribute to their devotion and courage throughout the struggle. In front of the Hancock mansion in Beacon strec#” Gov. Hancock and his son united in making the presentation a memorable one. It is interesting to note in pass- ing that the Bucks were under the com- mand of a colored man, Col. Middleton. In Connecticut there was great dif- ference of opinion concerning the wis- dom of allowing colored men to enlist in the Army. The quension was hotly debated in the Legisla- ture several times. Those who ad- vocated the measure were defeated when the bill was put to a vote. There came a time, however, when it was dif- fleult to get recruits. Then it was that the Colony of Connecticut decided to form a corps of colored soldiers. A bat- talion was soon enlisted and a company was commanded by Col. David Hum- phrey, who had been commissioned lieutenant colonel by Congress and had been appointed aide-de-camp to Gen. Washington. But this company was not the only unit of colored soldiers from Connecticut who saw service in the Revolutionary War. In many of her white regiments both the bond and the free might have been found. Rhode Island Passes Act. In Rhode Island the sentiment favor- ing the enlistment of colored men was so strong that the Genetal Assembly passed an act to enlist “every able- bodied Negro, mulatto or Indian man slave in the State.” They were placed in either one of two battalions, Rhode Island, therefore, was the first of the Colonies which voted to send regiments composed entirely of Negroes into the fleld. In March, 1731, the Legislature of New York passed an act providing for :Ikl)e raising of two regiments of colored en. Since there was such a great differ- ence of opinion concerning the question of allowing colored men to enlh&q. it was finally submitted to a Committee of Safety composed of such 3 men as Dr. klin, Benjamin Harrison alley Forge Thomas Lynch, with the Deputy Ofi ernors of Connecticut and Rhode Island, (Continued on