Evening Star Newspaper, March 6, 1927, Page 45

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

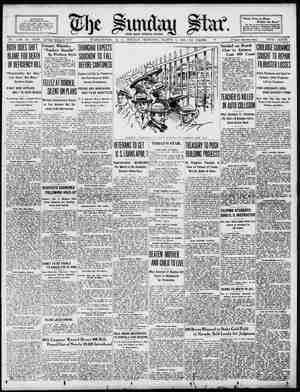

EDITORIAL PAGE NATIONAL PROBLEMS SPECI Part 2--16 Pages AL FEATURES \ EDITORIAL SECTION Che Sunday Shae Society News WASHINGTON, D. (., SUNDAY MORNING, MARCH 19217. 6, INCREASED JURISDICTION OF U. S. ISSUE IN PANAMA Misunderstandings Arising Over T l‘eatyl of July 28, 1926, With Central | American Repu BY WALLACE THOMPSON. § s and the Re ama signed, on | } treaty for “the | tlement of certain points of | difference which have arisen | the exercise by the United vereign in the This treaty, ich was rawn up at ¥ praa’s request and sort of substitute for the old Taft | agreements of 1804, 1905 and 1911, has | not yet been di n the Unite States Senate, while the Panama | Congress, after a lively debate, voted on January 26 to postpone its decision | and to send its plenipotentiarics back ‘o Washington to see if the terms and | provisions of the document could not | be modified. | There is a world of misunderstand- ing and lack of understanding about what the trouble is. Dr. Ricardo J. Alfaro, Minister of Panama here, and chief of the plenipotentiaries who negotiated the tre: has just re-| turned to Washington, but he says| only that he has come to try to find! out what can be done. The Depart- ment of State is apparently receptive but a little siiff over the matter. The treaty was signed, officials there point out, and now to revise it will require that all the machinery of a new pro- tocol, new appointments, new discus. sions and signatures be gone through with, Document Already Public. The document itself has been given | 10 the public; the committee on foreign relations of the United States Senate released it on January 18. A study of the text—without taking into consid- eratfon the background and the di-| vergencies in the document from what Panama hoped from it—gives the impression of three major ele- ments which might bring disagree- ment. These are the provisions for. military co-operation, the methods of exercise of the right of eminent do- main as granted to the United States | by Panama, and the arrangements by which Panama is to pay the cost of highways to be built in her national territory with obvious military strat- egy as their chief immediate impor- tance, The press of the world—and of Panama—has been somewhat caustic on these very matters. But a deeper analysis of Panama’s own objections to the treaty show that the military phases, at least, are not the chief ground of complaint there. The in- creased jurisdiction of the United States right of eminent domain is, however, an important issue, not least because it was largely in the hope that the United States would recognize o more limited 1 overeignty in this new treaty, that the negotiations were In- stituted by Panama. The payment by Panama of a large share of the cost of concrete roads she does not need —or want, at least—comes still nearer 1o the real heart of Panaman objec- tions to the treaty, however, for it brings in the economic phase. From the beginning of the agitation for the mew interpretation of the re. lations of Panama with the United States, the public there has been urg ing a realignment of the business privileges in the Canal Zone. Basically, the objection has been to the happy- go-lucky way in which the commis. sloners in the Zone sell goods (which pay no Panaman duties and few United States taxes) to everybody who applies for them. Another Difficulty Remains. Another economic_difficulty which was not touched in the treaty was the sition of the Panama Railway owned by the United States Govern- ment), whose rates and varied busl- nesses like renting out delivery wagons were a loss of revenue to Panama and the Panaman people, without adequate advantage to the “defense of the canal” The Panamans also object to the provisions in the treaty for bonded warehouses in the zone and for free dom from port charges of canal ship- ments in Panama’s own cities. The economic problem is also involved in the failure of the new treaty to pro- vide specifically for adequate United States Government support for local insane asylums, leper colonies, etc. where ‘former employes of the canal re kept at Panaman government expense. To other words, a whale world of little things, having to do with dol- lars and cents, and yet having almost no tangible reality in an international negotiation have acted like sand in the vlinders of the once smooth-running United States-Panaman relations. When the treaty as signed was re- turned to Panama, the explanation of the commissioners of their failure to arrange these matters was that the | treaty as written was “the best they | could get.” The chief stumbling block was the Department of War, which was behind most of the stub. bornness and insistence of the De- partment of State in its negotiations on the treaty. The Panama Canal is officially under the control of the Sec- retary of War, and its defense is of primary importance in the entire Carlbbean and indeed in the whole world policy of the United States. The Department of War insisted through. out the negotlations that it must not be crippled in any concelvable i its freedom of action for the defense—and the cconomic comfort of the canal garrison and its civilian appendages was firmly insisted upon In addition. Panaman Grievances Ignored. Panama has grievances, and pre- | sented them, but when the treaty was completed and signed, most of Pana ma's poor little eggs lay broken be- sido the basket. An old Spanish prov- erb tells the story: “If you strike an egg With a rock the egg is broken. If you strike o rock with an egg, the egg is, broken.” The situation as regards the treaty could hardly be expressed more clearly, for virtually everything which Panama hoped for was broken either by her insistence or, equally, by the insistence of Washington The history of the negotiations which resulted in the present treaty is a long one, but some understanding of them is necessary both to appre ofate the position of Panama and to understand that of the United States, The ‘“organic act,” o to speak, of the Panama Canal is the treaty November 18, 1903. Article 11I of that document gives to the United S a grant of virtual sovereignty which has, however, been the subject of much discussion and reinterpretation. It reads: . “The Republic of F to the United States nama grants I the rights, | exercise by | States | of the present treaty. | also, | bli Explained. and described in | which the United | es would pos if 1t were the | sovereign of the territory within | which said lands and waters are lo- | cated to the entire exclusion of the | the Republic of Panama | such sovereign rights, power | mentioned Article 11 't an; authority Meld To Be Perpetual Grant. | The United States has always held | hat this clause is a general and [\Fr-]i petual grant of sovereign authority in | he C Zone, while Panama con- | tends that by the nature of the treaty and by its other clauses the grant is limited, being defined and concerned with the building, operation and de- fense of the canal only. The Panaman defenders also hold that Panama has a right to ask and to receive, at some future date as that on which the 1926 treaty was brought up, a restatement and limitation of the grant and a limitation of the sovereign rights under which the United States has from time to time | taken up additional grants of lands and has required more and more co- operation of the Panaman government and of its people. Former President Belisario Porras, who initlated the negotiations for the 1926 treaty, once expressed the Panaman attitude to| me in these word | “From day to day the political and | financial necessities of the United increase in importance, and | for Panama it is of vital interest to | fix definitely her position with to the canal, now completed “fix _definitely” for the future Pan- ama’s relations to the canal and to the United States in the canal was the prime object of the negotiation or The Taft agreements had in a way | limited the sovereignty of the United States by the acceptance of definite privileges and the stipulation of cer tain co-operation that would be ex- pected from Panama. For instance, Panama agreed to a limitation of her customs dutles to 15 per cent ad valorem for the convenience of the ‘canal construction, and it was because of the existence of this and similar arrangements that Panama was So apxious to have the Taft agreements abrogated—which was done by a proc- lamation of President Coolidge, effec- tive June 1, 1924. It was hoped, next, that the United States would agree in the present treaty to a more satisfac- tory limitation of the broad powers given in the treaty of 1903 than had obtained in the Taft agreements. Result Felt in Panama. | The result has not been satisfactory to Panama. The Department of War of the United States declined frankly and firmly to give up its farreaching rights of taking over Panaman terri- tory In time of war or in preparation for the defense of the canal even in time of peace. It declined to modify basically the provisions for the com- fort and economical livinz of canal employes and garrison through the operation of the Canal Zone commis- saries. It held to the letter of the 1903 treaty in all the ways affecting in the slightest degree the convenience and security of the canal defense and operation. When the treaty was finally signed the co-operation of Panama in the defense of the canal was even more definitely expressed than _hefore. Panama agreed, for instance, to “con- sider herself in a State of war in case of any war in which the United States should be a belligerent.” She granted, in peace as in war, complete control of the cables by the United | States and virtual control (thlnly; velled by Panaman_ administration) over aviation and radio, down to the licensing and power of removal of private receiving sets. Panama also agreed to the free transit, in peace as in war, of American troops through Panaman territory. These were among the matters settled far more definitely, with regard to military co- | operation, than had been stated in the 1903 treaty. Panama gained no ground at all in the course of the definition, however. Colon Boundary Fixed. The city of Colon acquired a per- manent boundary, which had long | been sought; but as agreed to in the treaty this 18 unsatisfactory to the Panamans, as they feel that it vir- tually botties up the city within sharp limits and makes normal growth im- | possible, for the Canal Zone virtually surrounds it. The island of Manza- nillo, long a sofe spot, is a question “definitely settled,” as was desired by Panama—but with the cession to the United States of its “use and con- trol in perpetuity!” The sharp definition (if mot the limitation) of the rights of the United States to eminent domain for the needs of the canal is achleved in the treaty—again at the request of Pana- ma, but hardly to her entire satisfac- tlon. Article 1 of the mew document provides that “should it become nec- essary for the Government of the United States to acquire private prop- erty in conformity with the grants contalned in said treaty of November 18, 1903, the title to the property shail be deemed to have passed from the owner thereof to the United States when the formality of giving notice has been complied with.” This “formality” being completed and the land transferred, the value is to be assessed by a joint com- mission of one Panaman and ons American, with a neutral umpire in case of disagreement. An exchange of notes attached to the treaty goes one step further, and provides that this neutral umpire shall be “a citi- zen of the United States of America who is known in Panama for his eminent qualifications for the posi- tion.” The treaty itself provides that { neither the work of the canal nor of the Panama Railway or any auxiliary works shall be “prevented, delayed or impeded” by the detalls of the evaluation. \ Canal Defense Paramount. The freedom of action of the United States for the defense of the canal is paramount throughout the treaty. | Article 10, in fac provides that regards aviation “the safety of the Panama Canal shall always be the | deciding factor.” Throughout _the | negotiations, the Department of War and the Amer n negotiators were immovable on all points that in any way encroached on the rights acquired or believed necessary to the militar: strategy of the canal. Panama ha never been very happy over the con- demnation proceedings which have in the past 23 years enlarged the canal { Note: In the last four months the world has been amazed by the rise of a new China, and has been asking how it happened so sud- denly and what it means. One of the keen- est American observers of Oriental affairs was on the ground when it happened. In this and following articles Upton (lose (Prof. Josef Washington Hall) gives an intimate plcture of this new China and of the vast revolt against white supremac v throughout Asia. Mr. Close was for seven vears an editor in China, was once chief of forelgn affairs for Marshal Wu Pei-fu and is the author of “The New Outline History of China,” “In the Land of the Laughing Buddha" and other books which have at- tracted wide attention. In his second article, to be published tomorrow in The Evening Star, Mr. Close tells how diplomacy has so jar failed to touch the real issues of the Chinese situation and how China intends to carry the fight to the finish BY UPTON CLOS N the last cight months 1 have traveled 20,000 miles in Asia, visiting all countries from Siberia to Turkey and investigating the growing revolt of the Eastern Hemi- sphere against the white man domination. T made this study after 10 years of intimate contact with developments in China, Japan and Asiatic Russia. All through Asla I heard it sald, “The white man’'s day of reckoning has come.” Beneath my eyes I have seen in China the rise of a new nation, a China which bhas the making of the mightiest nation of the world. This China in the last four months has assumed the leadership of Asia against white domina- tion, mobilizing her vast natural resources, dustry, high intelligence and huge population for this end. T arrived in China early in September. By radio we had learned of the sefzure of two Brit- ish ships at Wanhsien, on the Upper Yangtze. The British captain sald, “If we don't take the most drastic means of retribution over this it means the end of the British empire has begun.” 1 was heading for the Yangtze Val ley when that drastic action was taken. Wanh sien was bombarded and some hundreds Chinese citizens were killed This was intended to put “the Chinese back in their place,” as the British expre d it, and was expected to restore PBritish prestige. In- stead it united all the warring factions in China against the British and in a campaign to end foreign domination in China. ¥ K ok K The ships had been seized by Wu Pelfu, who was backed by themselves, and it was against Wu's subordi- nates that the punishment was directed. Wu' rivals in Peking immediately backed his troops by demanding an Indemnity and an apology from Great Britain. The Cantonese forces, who were driving against Wu, offered to join him in fighting against any further British aggregsion. I arrived in Hankow in time to obserfe what an enormous effect this incident had. For three years there had been a standing joke in the Yangtze Valley. It was Sun Yat-sen’s “punitive expedition” from Canton against Wu Pelfu in the Central Provinces. It had got under way many times and always evaporated far away from Hankow. An ex- pedition was under way at the time of the Wanhsien incident, but it was struggling in the mountain passes leading to the Yangtze Valley from the south. No one expected it to get any further than previous attempts and no active measures had been taken to stop it K ok ok ok Wu's hands were tied €0 far as supporting his subordinate went, because he was mainly reliant on British friendship for his supplies. He did nothing to support his commander at Wanhsien. So when the wave of Chinese re- sentment swept the country he was in a false position. Nationalist propagandists took full advantage of this situation. His army was aiready weakened by lack of pay and rivalries among his commanders and was ready to listen to the Nationalist cry for unity against the foreigner and accept Nationalist pay. One night as Wu was painting a picture at his Hankow headquarters shells began to fall around the building. He went on painting, but soldiers of the British UPTON (LO! out wildly to learn if the had suddenly appeared were coming from a divis Wu's own officer. Wu word to two supposedly loyal commanders to > the mutineer, but they replied they were t home to Marshal Wu that night. Wu rted to withdraw in his private car, but it iled outside Hankow and he had to s, accompanied by his wife and {hrec faithful staff officers, before he found loyal troops. Two days later the vanguard of the Cantonese army was welcomed into Han- kow and the world was startled with the in formation that the Nationalists had at last veally come into control of the Upper Yangtse Valley. N They sion sent his staff sent tional 1rmy found the shelis under Gen. Lu, * %k % Xk Through a curious set of circumstances 1 then came into close contact with the Can- tonese. 1 w captured by troops of Sun Chuan-fang, who had left Wu in the lurch and planned to make himself master of the Yangtse Valley by cutting the precarious line of communications of the Cantonese and en- veloping their forces. 1 was taken to Shanghai by Sun's officers, who boasted of what was going to happen. Tmmediately on my release I went to Canton to see what sort of men the Cantonese leaders were and in talks with them 1 told of the boastings of Sun’s officers. Can- ton immediately sent out a counter-force which cut the lines of Sun's army and made it fall back on Shanghal. I was thus brought into contact with the capable young leaders of the Natlonalist move. ment and saw some of its remarkable develop- ments. I found the present Nationalist movement to be the result of a combination of two move- ments which have slowly gained growth for some y The first factor is the old » tionalist party, founded by Dr. Sun Yat-sen in 1904 for the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty. After the success of this revolution in 1912, Dr. Sun's party fell into disrepute through its lack of ability to organize politics, and for a decade it was the foot ball of military adven- turers. * % ok % The second element is the student move ment which swept the country in 1919 as a reaction to President Wilson’s “betrayal” of China in asquiescing in the Japanese retention of Shantung Provin The students of the middle and higher schools, men and women, d so well they were able to pre- signir the Versailles treaty by China and went on to overthrow their own government, which was obvio! selling out to Japan Following this vi excesses wh vent th students went to into disrepute, but they h cir ability in con certed action se since. The most s the st the shooting of demonstr British police in Shanghai in May, 1925. The Canton movement, which was then in the throes of reorganization following the death of Dr. Sun, immediately took up the cause of the students, and a parade of protest brought on a clash between Chinese and foreigners (mostly British) in Canton, and another so- called m » of defenseless Chinese by for- eign machine uns took ce. The result was the drastic measures taken to kill the trade in Hongkong by the Cantonese and the coming together for a unified purpose of the student movement of the north and the Nationalist group of the south. ek About this time organization ability, brought tionalist party by Michael Borodin, 8 who had been lent as advisor to . Sun by Abraham Joffe, began to be evident. Local committees (or Soviets) began to appear and dominate local affairs in every county and province in China, although more openly in the south. The movement spread like wild- fire. The anclent Chinese secret socleties, such as the Triads and the White Lilies, in many cases, transformed themselves bodily into Soviets. These societies are often called the Masonic bodies of China. They sprang up at least 2,000 vears ago and exist in every town and city and are strongest in the south. It was their support which made the Talping rebellion such a menace in the middle of the nineteenth century. They financed Sun Yatsen in his long campaign against the Manchu dynasty. Disgusted with political disruption since the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty, they had withdrawn largely from political activity until the new Natlonalist propaganda recaptured their imaginations. $ok ke # The cry of the new movement is “China for the Chinese"—"abolition of properties which tend to make the white man regard him- Self as a superfor being in Asia"—“unification of China” and economic devejopment of China with Chinese capital. Last October the reorganization of the new Nationalist party took place in Canton. Dele- zates appeared from the locals in every prov- ince of China. A commission of 22 members was elected to be the supreme authority In China. This, in turn, operates through an inner “committee,” consisting now, for prac- tical purposes, of three outstanding personali- ties: 'T. V. Soong, financial genfus; Gen. Chang Kal-shek, military organizer, and the trusted Russian, Michael Borodin, a superpropagan- dist. Of the part played by Russia at large in buflding up this movement, supplying mili- tary trainers and protecting it from attacks on the part of northern China, I will tell fully in_another article. Because money speaks louder in China than in any other country in the world, the contri- bution of the American-educated young finan- clal genfus, Mr. Soong, requires first mention. He is the son of one of Dr. Sun’s associates in his early revolt against the Manchus. His father was killed and young Soong, who was born In Shanghai, was left the protege of Dr. Sun. Eventually Sun married Rosamond, elder sister of Soong, who s a very decided personage herself, as shown by one proposal to elect her president of the new united China. Soong was sent to Harvard and after graduation from the School of Business (1917), he had training in an international banking corporation in New York. X Upon his return to China Dr. Sun put him on the problem of the tangled currency In Canton Province. At that time Canton money was worth something Iike 40 cents on the dollar. Soong at once concentrated the entire finances of the province in one state bank of which he, a lad of 32 years, became president. Later “ontinued on Third Page.) : ¢ the flare-up a; sac SHANGHAI BUILT ON SWAMP SITE; |COST OF PRODUCTION EXCESSIVE NOW WEALTHIEST ASIATIC CITY | America Has Immense Trade With Chinese Port for Which Armies Are Battling—4.000 Nationals Live There. BY DREW PEARSON. Shanghai, the New York of the Orient, for which two Chinese armles are fighting and the foreign set- tlements of which 10,000 American, British, French and Japanese troops are defending, once was a malarial swampland, given to forelgn traders becauso the Chinese felt sure they would become discouraged develop- ing it and would go away, leaving their work behind them. * American Marines who paraded in Shanghal probably had no idea that the beautifully paved boulevards along which they marched are supported by wooden piles driven into the old swamp. Today Shanghai ranks as the wealthiest and mightiest city in Asia and one of the buslest seaports in the world. Her water front, once an ex- panse of sand dunes, now is worth thousands of dollars a_square foot. The magnifience of the buildings which line this water front is sur- passed only by the skyline of Man- hattan, Four thousand Americans live in Shanghal the year round, with an additional thousand taking refuge there at present because of anti- forelgn riots in the interior. Here more than half of the American busi- ness with China is transacted, a busi- ness which has tripled within the last 20 years. In Shanghai also are the central offices of 6,000 American mis- sionaries who ordinarily live and work in_the interfor. Shanghai is the chief industrial center of China. To it have flocked thousands of Chinese workers for em- ployment in forelgn operated cotton mills, tobacco factories, silk fillatures and shipping warehouses. W among these workers, who dwell in the utmost squalor in the Shanghal slums, that Cantonese are concentrat- ing antiforeign propaganda. Strikes and boycotts springing up in these mills would be far more dlsastrous to the forelgn settlement than an out- side attack. A strike of Chinese labor would first of all cut off the nightly disposal of sewage which depends en- tirely upon hand labor. Next it would cut off the water supply, the lighting from a strip 10 miles on either sde of the ditch to an irregular territory power and authority within the Zone mentfoned and described in Article IT of this agreement and within the limits of all auxili lands and immensely increased in area, and em- | bracing virtually the entire watershed (Continued on Fifteenth Page.) + system and the telephones. Through Shanghai comes 49 per cent of the trade of China, which brings also 49 per cent of the tariff revenue. This is the secret of the present struggle of Chinese armies for control of Shanghai. Whichever fac- tion controls this key city also gets a tremendous annual income. There is a weird mixture of races fighting on opposite sides in defense and for the capture of Shanghai. Despite the growing feel- ing of “Asia for Asiatics,’ most of the French army now in Shanghai is made up of little yellow rhen from French Indo-China, who to the stranger resemble the Chinese in every wa: About half of the British defens troops are big brown Indians, brought up to help make Asia safe for the white man. On the other hand, one of the crack regiments of Chang Tso- Lin’s army is composed of Russian mercenary troops, which have hired | out to fight for yellow masters. Shanghai has become a great port only because it stands at the mouth | of the Yangtze River, the Mississippi u‘! China. The word Shanghai means “By the Sea,” and although the city originally fulfilled the correct inter- pretation of its name, the silt washed down by the Yangtze has built up a delta around it, until it now stands | 13 miles inland. H In order to protect American lives and property American gunboats main- tain & patrol up the Yangtze for over seventeen hundred miles, which is as far as the mouth of the Mississippi to Hudson Bay. The Palos and Mon- ocacy, two American gunboats, which draw only 814 feet, even proceeded up the river beyond the gorges from Ichang to Chunking, in which district numerous American missionaries live. Protection for American shipping is especially necessary along the upper gorges of the Yangtze because of the frequent attacks which junkmen make upon steamers. Junkmen make their living by towing their junks up the rapids hand-over-hand, at a speed of 4 miles a day, and they resent com- petition by ~ steamers. Since the average junk can stand only three round trips before it falls to pieces, freight rates are high. | American steamers, which take freight at. lower rates, are frequently fired at along the gorges, and one American steamship agent recently was beaten to death for accepting a cargo. st Mental problems of University of Minnesota students are to be looked into by a neuro-psychiatrist, employ- ?lfmmflmdlcreatedbyln!l.h\ ees. IN SOVIET, ASSERTS BAKHMETEFF |Peasants Find Their Produce Does Not Bring as Much Clothing or of as Good Quality as Before Red Control. BY BORIS A. BAKHMETEFF. History is unmerciful to those who challenge life. The laws of human nature, of economic necessity, cannot be violated with impunity. In this simple maxim lies the key to the un- derstanding of the Russian situation. Much has been said about the won- derful recuperation of Russia. Only the other day one heard that Russia may take second place as world oil producer, yielding to the United States only. Now, what are the facts and what is their meaning? ‘The economic recovery of the Rus- sian people, only a few years ago so near the abyss of complete destruc- tion, 18 a positive and most encourag- ing fact. The nation has shown re- markable vitality and has survived a deadly social epidemic. In particular, agriculture, which represents more than 80 per cent of the population, has reached more or less the pre-war con- ditions. Industrial output, which sank to naught during the first years of Bolshevist rule, has also approached pre-war figures. To outward appearance, Bolshevists are in full control of the country. Fig- ures measuring economic reco are used to testify in favor of their sys- tem. And still every official utterance bespeaks anxlety, reflects an ailment rooted in the very essence of the sit- uation. In a word, the problem is—the rela- tion between peasant agriculture and industry, industry operated, as it is, by the Communist state. In fact, yielding to the pressure of the peas- antry, the central government has more or less withdrawn from the vil- lage. The peasant succeeded in ac- quiring a certain self-dependence, in heing left to lvie and to till the land according to his own ways and tra- ditions. On the other hand, the Commun- ists retained full control of industry. The mills foreibly confiscated from the old owners are held as property of the State and are operated by officials on behalf of the government. Russia presents an example on unprecedented ecale of state owned and state man- aged industries. At present these mills are reconditioned to produce about what they used to before the revolu- tion. Thus, industrially, Russia had returned to where she was 10 years ago. Such is the result of the experi- ment when viewed dispassionately and objectively. The oustanding feature, however, is | rant accusation of the present system, not quani it is the cost of produc- tion. Red tape, inefficiency, all the in- herent evils of the system, result in prices being preposterously high. The peasantry, when exchanging | their crop for shoes, textiles and other | s necessities, have to pay twice—three times—as much as in the old days.! A striking fact from a recent of- ficial perfodical: In ‘the Autumn of 1926 in central Russia the price which the peasant had to pay for a pair of beots was the equivalent to the crop of nearly two acres of rye. Such distortion s obviously a flag- and it is natural that an endeavor to lower prices, to close the chasm be- tween industry and agriculture has been the official goal year after vear. But life is inexorable. Conditions, in- stead of improving, have grown worse. In 1926 the peasant was paying in measures of grain from 30 to 50 per cent more for manufactured goods than a year before. No wonder there has developed a certain slackening in the market. The peasant at present appears to be refusing to pay ridicu- lous prices; he is unwilling to take goods of inferfor quality and poor as- sortment. So the Russian drama is further in- tensified in its everlasting conflict, that between the masses of the pop- ulation, impersonating the forces of life and the Communist masters, per- sistently trylng to force life into the narrows of fanatical doctrine. (Covyright. 1927.) Japanese Banks Rolling in Wealth Notwithstanding the cry of depres- sion from various quarters the banks of Japan are simply rolling in wealth, and are out begging not for lenders {of course, to seek power by direct ac- | Peasant British Hit Ha BY FRANK H. SIMONDS. HE warning note which the Br h government has marks one more stage in most remarkable of post international struggles r 10 years the Soviets have been carrying on a war with the British nation. Since 20, the British governments, Coali- Labor and Tory, have heen t ing to make peace with Red Ru. In the first days of the Russ Revolution, after the arrival of Lenin and Trotsky brought about a separate peace beiween Russia and German the British, like the French and American governments, undertook to support the various anti-Red leaders, Kolchak, Denikine and Wrangel. When the Reds were cesstul against the Poles and nearly took Wa the British policy changed abruptly. After the defeat of the Rus- slans before Warsaw in 1920, Britain began a long series of proposals for peace Always, however, Red Russia has continued to regard the British as the real enemy of the Revolution. Lloyd George's effort to bring Russla back into the circle of European nations failed at Genoa and the Russlan sep- arate treaty with Germany wrecked the Genoa conference. The great disaster of Chanak, which fatally shook British prestige in all of Asia, was in part the result of Russian sup- port of the Turks, who received muni- tions and other aid from Moscow. Labor Party in Power. A year later Labor came to power in Great Britain at the election of 1923. Labor had always been sym- pathetic with the Russian Revolution. When Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister it was accepted as in- evitable that Rusia would be recog- nized. But although this took place in the Spring, in the early Fall Mac Donald w: defeated and forced to resign because of Soviet intrigues in Great Britain. During the general strike last May and the coal strike which followed, bolshevist money was freely sent to London to support the strikers. Even before that time the Daily Herald, the newspaper of the Labor Party, was subsidized from Moscow. It is not, however, the bolshevist activity within the United Kingdom which has been dangerous. British labor has, on the whole, very steadily resisted the influence of the bolshevist sympathizers, although the extremists have been steadily affected by it. Actually it is in the empire that Moscow has been carrying on its real war. India and China are the true fields of Soviet activity. Each year there is graduated from one of the old Russian universities not less than 500 students who have been trained as propagandists for the precise purpose of carrying the war into the Asiatic territories and spheres of influence of the British Emplire. Influence on Cantonese. The whole Cantonese movement, which played such a part in the Chinese revolution in recent days, is profoundly influenced, if not directed, from Moscow. The later policy of the bolshevists, defeated in their direct attack upon European _capitalistic nations, is expressed in this attempt to cripple and destroy the trade and the influence of the British in the Far East. Actually the bolshevist campaign against Great Britain is_being pre- pared against India. In Beluchistan, in Afghanistan, in Persia, Soviet in- trigue is proceeding. Troops and air- planes have been concentrated facing the frontiers of British Indla. Agents of the Reds are at work among all the tribes and races, not only of the border, but in India itself. - But while this propaganda is going forward, the Chinese fleld is the most promising for immediate activity. The boycott against British goods strikes British trade. The loss of the Chinese market brings unemployment in Great Britain. Unemployment not only cripples the government, but increases domestic unrest and dissatisfaction. The unemployed add to the burdens of the British treasury, their dissatis- taction makes a domestic political and soctal problem. Broad Aim of Reds. ‘The old idea of the bolshevists was, tion—to rouse the working men in all Buropean countries, to overthrow the governments, to set up Communist states modeled upon the Ru In fact, their idea has alway world federation of all Communist They have carefully sup- pressed the idea of Russian national- ist_control in any such union. Western peopies, however, resisted | the Russian efforts. Communism | within the various western countries | has made little or no progress. Bol- shevist defeat has become unmistak- able. As a consequence Moscow has turned to the effort of exploiting the ‘weakness of the European capitalistic states in Asia and in Africa. Red money appeared in the French war against the Riffs. And there, as else- where, Red tactics were the same While' the Riffs were supplied with money and_arms to kill French sol- diers, the French workingmen were deluged with propaganda rousing them against the war their country was carrying on. The same process was repeated in Syria. It is only against the British, how- ever, that the bolshevists have been able to_achieve very material results. The whole Chinese affair has been from the English point of view a dis- aster without limit. Meantime no one knows even ap- proximately what is going on in the interfor of Asia. Mongolia has prac- tically passed under Russian influence. In a curious fashion Revolutionary Russla has resumed the policy and purpose of the old Romanoff regime and the anti-British purposes which were the outstanding circumstances of the last decades of the nineteenth century have been completely accepted. All British Now Aroused. In this situation the British public has become tardily but generally aroused. The spectacle of a Russian representative in London, acting not merely as a diplomat but also as the but for borrowers. This year's first weekly statement of condition of the Tokio clearing house shows the high- est figure In the house's history. Ad- cording to this report, the deposit ob- ligations of the consolidated banks of Toklo alone stood at 2.,000,522,000 yen (about $1,000,000,000), or nearly $20,- 000,000 more than at the commence- ‘ment of 1926. | Th ncial horizon, therefore, M&m It is ex- #ts minimum rate. political agent of a nation which is seeking to disrupt the British Empire, has become intolerable. Thus Cham: berlain's latest note of warning s, in fact, a threat to break off commercial relations. SOVIET STRENGTH WANING DESPITE GAINS IN CHINA Power Increasing in Russia With Tendency Toward Capitalism. rdest by Reds. policy of attack upon Great Britain in Asfa would be continued and extended. Such reports as reach the west from Russia, however, make it fairly clear | that a real change i3 beginning to take place. Little by little the peasants are at last becoming politically potent. And for the peasants the dominating feeling is hatred of the city, and therefore hatred of the boishevist leaders and rule, which is based upon the cities and is the resuit of the ac- tivities of men and women who belong to an industrial, not an agricultural, world. The bolshevists have been tolerated by the peasants because from them the peasants obtained the land in the revolution. But it has not been possi- | ble for the Reds to obtain acceptance for their communistic ideas among peasants. On the contrary, nat only have the peasants rejected the idea of state ownership of the land, but they have with growing frequency killedj the agents of the Soviet governmenty who have endeavored to collect taxes. ‘Weakness of Soviet Shown. Today the Russian Soviet regime lives because of the government mo- nopolies. It derives its revenue largely, from the oil and gold and other prod’ | ucts of state property, which it sells directly to foreign countries. It does not dare to attempt any real policy of tax collecting. But the weakness here disclosed s accentuated by the fact that it is unable to provide the peasant with the things which he needs. It cannot provide roads, it cannot even provide markets, it can- not supply goods. The great evolution which is taking place within Russia with the passing of time is this rise of the peasants to political power. Actually there is ap- proaching an intermediate stage be- tween the old Marxist Communism, which was represented by Lenin, and the peasant state, which many experd- enced Russian students predict is as- sured within a decade. Stallin and gakov, in fact, represent this transi- on - The peasant movement will oer- tainly bring to power capitalistia ideas. So far from seeking to destroy the idea of property, the peasants, now masters of their own land, will prompt- ly reestablish capitalism, so far as land is concerned. Thus, profound as have been the disasters which Russian Soviet policy has inflicted upon the Western na- tions, upon Great Britain first of all, it is far from impossible that the worst has already been seen. And it is also far from unlikely that the British government is now aware of the domestic developments in Russia, concerning which it must have far better information than the unofficial world. British Labor Sees Light. Nor is it less clear that its pesition is strengthened by the fact that Brit- fsh labor is becoming increasingly aware of the fact that it is the real vietim of Soviet activities in Ckina. Unemployment in Britain is an ob- vious consequence of the Chinese bo: cott and attack upon Britain, which have been stimulated and incited by Soviet agents. And, at last, labor is glving evidence of resentment and even willingness to support govern- mental reprisal. Meantime for the whole world the British course must be at once inter- esting and important. Soviet activity in China, while inflicting great finan- clal losses upon Britain, has destroyed labor sympathy for the Reds. ‘The hand of the Tory government has now been forced. The British people are up in arms and public opinion is more excited than at any moment since the Zinoviev letter up- set the Labor government. Were the British government now to pro- pose a general policy of reprisal and blockade against the Red regime, the consequences might be considerable. They might even hasten the trans- formation now inevitable within Russia. British policy toward Russia has always been influenced by the domi- nating necessity to reopen Russian markets and regain access to the relatively cheap food supplies of the old empire. Along with this has gone the realization that a hostile Russia could do incalculable injury to all British interests in Asia. All British efforts at conciliation and restoration of commercial interchange have failed. All the advantages of restorad coni- mercial intercourse, so far as it has come, have been Russian. America. which has not recognized the Red regime, has actually fared better at Russian hands. Now the British seem about to change their policy. Their warning may have effect. Moscow may mod- erate its hostile operations for the mo- ment. But only in Asia and agalnst Britain can it actually pursue its pol- icy of war against the capitalistic world. Therefore an accentuation of the Anglo-Red troubles seems assured. Asia has become the final battleground of the Reds. China is their supreme bid for the world revolution. (Covyright. 1027.) Deadliest Enemies of Man Are in Cities “The deadliest enemies of man at the present time are not disease, war and famine, but the industrial con- ditions of the cities.” This is the econ. clusion of Dr. Warren S. Thompsen of the Scripps Foundation for Re- search in population problems at Miami University, following a com- parison of life and death records in town and country. The natural increase of populatien is considerably greater in the country than In the city, Dr. Thompson pelnts out. A greater proportion of country women than city women marry, and the probability is that they marry earlier, so that they establish their families at an age when they are most likely to have children. Farmers and miners, groups which are distinctly have the highest average in ._I’-'fi familles, Dr. Thompson points out. Managerial and professional have the lowest average. Rural z- tricts not only produce more children, but they have lower death rates than the citles, the studies show. “It would seem clear beyond p tradiction that from the standpoint ‘of population growth the rural communi- ties stand at the top of all groups in the United States,” Dr. Thompson the ‘twa But_even this reprisal can really states. “The incontrovertible conclu- have little menace for the Reds. Most | sion is that rural conditions more near- of the Russian trade is with the United States and Germany. German pene- tration is increasing. Were the bol- shevists destined to remain in com- Japan will plete and unchallenged control for|ence have years to come, it is certain that their y ly meet the vital needs of human lif :;lu.:n:\:hl:‘ condllil'onl‘ If this l: » how much more significan it is that sanitary and uu‘l:d lfit scarcely begu ‘ministe: to rural needs.” ” . 5