Evening Star Newspaper, February 26, 1898, Page 17

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

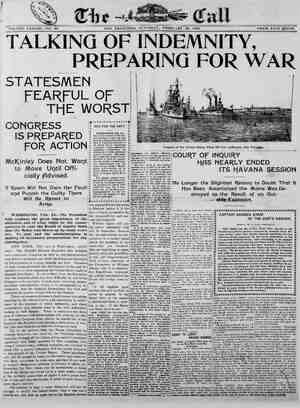

e/a Bs NOT AN ACCIDENT Views of an Expert in Explosives | on the Maine Disaster. a THE FACTS FIT THE MINE THEORY Nature and Effect of Mines, Tor- pedoes and Magazines. ION - OF THE FORC destroyed the in the harbor Havana may be | ed to those by the warships t, Aquida- up, the the B Chilean na wars. and force S$ used in these th t from m understoc Inst ts produc » been u: w 3 clusions th upset by likely to be oard of inquiry was sunk which cot Maine. Only s of the Aquida- i agi ions of the The photograph her offi how her nverted almost instan- forward. » effect on the er her port side powerful AMBITION AND WORK SS The Two Requisites to Success on the Stage. ns U automobile VIEWS OF A WELL-KNOWN ACTOR Advice That is Equally Good in Other Walks of Life. ad es LUCK PLAYS NO PART = —e we for The Evening Stor. ISUS, by the SS. McClure Co.) We I NOT SURE ' at I can play the leading lady parts in pieces better they nted, young woman wrete me in Chicago, a week or} two ago, “I wou offer you my ser- I am li with a ye agree wita m y dramat- ake me on the > make a b: who persist trical after the ribbor if I try to point they are apt to years of hard ion ought to make a valuable to his feliows. stion of vanity in n where they may do nly thing I am vain of is hard coun- EXPLANATORY SKETCH DRAWN BY TR HOLLAND, !pewer, is a magnificent are now}! er dirigible torpedo we know anything abou Power of 2 Torpedo. Is there a Whitehead, a Si Edison, a Patrick or a Schwarzkopf torpedo capable of instantaneous! nverting a battle ship r of flaming ruin’—unless one s be at the same moment © into a of her mag expleded? The is not more t Althoug be made there a ize of eleven feet hes bursting charge of these torpedoes an 110 pounds of guncotton. ead torpedoes are now to eet jong, I do not think yond the standard inches long and nine thick. Fired from a tor- at a steel ship lying within the OW yards the White- N control from arting through stion with shore, ater at an initial velocity of thirty- two knot hour, propelled by its own y. driven by a self-contained com- ne of forty or fifty horse- war machine. only do the details of the de- he Aquidaban and Blanco En- negative the suggestion that even th rful terpedo could have wrought such havoc on the Mainc—unless her m: forward had been pleded by the torpedo, but observations in other directicns on the force and effect of high explosi discharged under water ike forbid the torpedo theory. Vhat inference do the facts warrant in to a magazine explosion? Whether result of 2 torpedo exploded from or any ‘other conceivable cause within the ship? The Mine Theory. scarding the torpedo on the magazine there is nothing left but a A study of the Aquidaban and ‘9 Enealada explosions confirms inde- observations of my own; the facts of the Maine disaster do not fit any other But not e than a mine theory. They unanimously tend to support that theory. Nor is it necessary to suppose that the Maine was anchored over an old mine. A new mine, for that 1 purpose, could have been put down in an hour's time before the Maine was assigned to her station. The uld pave been taken out fn a boat ight and dropped overboard, . its own weight holding it in posi- tion. One ordinary ground mine containing pounds of high explosive is perfectly competent to do all the damage that was inflicted on the Maine. We ¥ suppose a ground mine with its contact-make 1d shore connections to be thing like what is shown in the plan sketched to accompany this article. er commanding the contact-maker battery on shore, from which an wir maker D, fic le: A—-B., to the contact- , caps down, and harm- How to Do It. By pressing a button he releases the con- tact-maker from its anchor, C, and permi and assum tion. s the position F ready for ac- In the conta maker we will assume a charge of, say, twenty pounds of high ex- plesive, which is fired by the ship's bottom coming in contact with the caps pointing upward, as in F. This explosion causes imme the explosion of the nine E. Now, suppoce there is a current (as there is in the harbor of Havana.) The contact- maker will drift away on the curr toa ition G, which will still bring it directly beneath the hull of a ship riding at anche If the mine were under her bow, the con- tact-maker would now strike about amid- ships. could not have blown up the . because there Is absolute evidence that when the magazines were closed and lecked for the night—aboyt an hour and a half before the explosion, the temperature ef the magazine was only 59 degr It is not conceivable that in the interval this temperature could have risen to a sufti- cient degree to explode coal which requires incandescenee. Spontaneous com- bustion in the cozl bunkers is impossible for that reason. The Combustion Hypothesis. Nor could the spontaneous combustion oil Nor of oil waste cause it; for nothing like waste ever left in a magazine. cculd the smokeless powder in the 1 zine have undergone chemical changes in any such temperature as 59 degrees. Nor could the short-circuiting of an electric light wire have caused the explosion; for the light is admitted to the magazines in a warship only through thick gias And all the wiring is outside the m wall. . In my opinion the war-heads of the Maine's tornedoes will be found intact. They were stored aft, not near the points of explosion, which cannot reasonably be attributed to them. What then is left ex- cept a mine? .As for the ridiculous, un- just and uncharitable charge of lack of ripline on board the Maine, the very fact that when the magazine was closed fo: the night its temperature was only de- grees shows that there must have been con- stent and careful ventilation of it. In wa- ters where temperature is as high as that of the harbor of Havana, 75 degrees or SO Cegrees I should say, only magnificent ven- tilation would keep a magazine as cool as that. Line of Lenst Resistance. The explosion which did the damage must have occurred on the port side of the ship, forward, either inside or out. Its foree was exerted along the line of leas resistance, toward the starboard where the forward main magazine w: situated containing 25,000 pounds of brown powder. Had that magazine been exploded it was quite capable of causing all the ruin which we know was wrought in the Maine, and a great deal more, too. But would not the line of least r ance in that case have been in exactly the opposite direction? It seems that this must have been the case. The explosion, indeed, of that magazine would have strewed the fragments of the hip all over the vicinity. The fragments shells we Know it contained would have been scattered all over Havana. not going to preach to deal of fun out of life, e Ue bit’ past fifty and play under my own hair, and my own name. But I will tell yeu, my young friends, the hard work that, according to my theory, is necessary to ste on the stage, no matter how well equipped you are by nature and education. Nature did very little for me. I am the first of my family on the stage, and I got from my father, who was a mechanic up in Connecticut, very little except the ability te work and the d@ermination to stick to it. His name was Crane, and when, as a bey, I made up my mind that I wanted to be an actor, I decided that I would still be a Crane. I've never had a stage name. So I siarted in with ro capital, no fine clothes, no special education and ‘no influ- erce. I didn't even have an opportunity, but I chought one would come if I waited long enough. Working for Nothing a Week. I had been with the Holman Opera Com- any a good many weeks, at nothing a week, and I mean it, when my first oppor- tu came It was in Williamsport, Pa., in Is%3. J was sitting ia the first entrance atching the stage, as I had watched it night in and right out, studying every bit of business, every change of costume, think- ing which role I should like to play best, when the stage manager told me Ben Hol- ‘as ill. The opera was “Somnambula,* ish version, and young Holman had pieging Alessio, the basso, a good nedy part. an do it,” Y said, without a moment's They all looked at me in as- nt, Some in amusem st. shaw,” said the elder Holman, to be rehearsed and you'd to learn the music. We've got to have body row." Weil, L can do it now want any reh ou. I get a good if lama “lee- I answered. sal and I know the as true. wrt in the strance w: too. I had learned every ing there in the first ympany. And I got missed a word or a ht Bea Holman was cast the heav- I sang it right and the next night is Devils- heard w as going on, and n effort and came to the theater own part. but the exertion killed art I know of. through, died not long afterward. His ill- ¢ gave me my opportunity. I was with Holmans for seven years, and when I wasn't at the theater I was with them them, their lodgings.. I never left and kept right on trying to learn part in every piece in their repertoire, ng until toward morning, instead of. skylarking after the performance was over. But all the time I realized that I would never make a musftian. I didn’t know the notes. I wanted to bé an actor. So I left the"Holmans and went to Crowe's Theater and played there in legitimate comedy. I didn’t get but $20 a week, but I was satis- fied. I was learning something all the time The Glamor of the Stage. to ambitious ears, may glamor of the stage— Ss no use making fun of It, for it ex- ists—draws toward the stage door so many women who want to exploit their vanity, s0 many men who covet ready reputation and big salaries, that I sometimes think there are actually more aspirants for hon- ors in this profession than in any other— especially than in those, such as law and medicine, where the laws require therough and systematic preparation. and I was sitting up until 5 o'clock, plenty of mornings, studying the old English com- qlies, putting ice water on my eyes to keep them open and pegging away at my book so I coukl be perfect at rehearsals next day. Not much “glamor” about that, ch? Watching for an Opportunity. I was taking every chance that came my Way and waiting for more. I was studying all the comedy parts in the range of old English comedy with the hope, and on the chance, that I might some day have an op- portunity to play them. I remember learn- Now, young man, or young. woman, I’m | ing letter perfect seven parts in a single for I couldn’t tell which one of them I might get a chance at, some day. The young men who want to “go on the nowadays—do ihey fancy such a pect’ How many weeks are they will- ing to work at nothing a week—with no part? How many years are they willing to study, on a small salary, with only expec- Why, a short time ago a young man in my company objected to understudying three or four parts. I reasoned with him, and at last I got mad, and I sald to him: “My young friend, the last week I was with the Hooley Comedy Company I played nine parts in four nights.” That settled it. When I made up my mind to give up comi opera and to devote my life to comedy, I realized that I was giving up a good deal of cash in hand for the sake of possible recompense. 1 was looking ahead to a prospect of excellence and de- liberately throwing over an offer to have my name printed in big letters as first comedian of the Alice Oates company with parts that would divide honors fairly with her. What is more, I was giving up $125 a week for a salary of just $65 per week, but little more than half as much. But Ambition and Work. A good many young men would take that extra $60 and immediate popular favor But I think it paid me not to do it. I was ambitious, and I am more ambitious now, today, than I was then. And after I was married, my wife was more ambitious for me than I was for myself. Ambition? I should say so. I fear de- terioration in my own work, in my com- pany, in my productions, as much now as ever in my life. Why? Because I am proud of what I have achieved by work, sheer honest work, work that has never igged and that will not as long as I am acting. Tam determined people shan’t say I “got it by luck.” It was work—and am- bition. ‘Crane's luck,” said Joe Jefferson not long ago when somebody spoke of me in that connection, ‘Crane's luck! None- sense; it's Crane’s worl And that’s just the reason why I am not ashamed to speak of it. I have never to my knowledge said, “I ean play that part just as well as So and So.” But I have always played every part just as well, just as hard, as I po: bly could and let the result take care of it- self, And what's more, Iam just-as afraid of failure today as’ I ever was in my life, Just as eager to guard against it. That's all, my young friends. Once started on the stage, don't sacrifice a pos- sible future for present cash. Don’t try to ar just because you nave made a hit. Don’t think about “the glamor of the stage." Don’t expect anybody to make “the opportunity of your life’ ready to your hand. Study, study, study and wait your chance, Whether you should start or not depends largely on how anxious you are to work, don’t you think so? WILLIAM H. CRANE. eh a Biting Sarcasm. From Puck. Sapsmith (indignantly)—“Grimshaw call- ed me a foo! again lawst night!’ Askins—‘What did you do about it?” Ps Seventy sentcans Phd tabe eS age fone. n't you know, ay why didn’t ‘say something original!” pees ee Aer a Teacher—“What do you know about the law of gravity?” £ - Pupil—“Oh, if I snicker in church I have to read two in the Bible when I get home.”. 's Weekly, LAND OF = THE CZAR Book Relations That Exist Between Gov- ernment and:People, REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTDYING OUT ——— r Peasants Are Well Treated and Are Perfectly: Contented. SYSTEM OF VILLAGE LIFE (Copyrighted, 1893 by Ewing Cockrell.) Written for The ning Star. HERE EXISTS TO- Te an empire with dominion over one- seventh of all the land on the globe, a country with a popu- lation greater than that of any other civilized power on earth nation ab- sorbingly interesting and easily accessible, und yet at the same time a land of which we Americans know practically nothing. I speak of the great Slav empire—Russia. The treatment by the Russian govern- ment of a certain part of its people, whose total number is not over one-quarter of 1 per cent of the whole population, has been graphically pictured to us. Of the treatment by the Russian government of all the rest of its people, the other 90% per cent, hardly a word has been said. The difficulty of getting into Russia and the suspicion with which foreigners are re- ceived have been made much of. But the ease with whicn one can travel in Russia and the hospitality of the Russian govern- ment and its people have not been reveaied to us. And I believe that +o any intelli- gent American a word about the real Rus- sia, about the every day relations of the Russian government with its people and its visitors, cannot but All my life 1 had h th police force of Russia, I had read the poor pecple in the ezar’s land, the farmers, factory hands, cab drivers others, were constantiy abused by the police. started for Russia, that looked upon with suspicion, Would be sure to come in contact w police in a very short while. his la dictioa came truc e With the Police. ning in St. Petersburg I started to drive to the “Bazar,” and called for a droschky. In response, two droschkies came racing teward me, and in a minute I was doing the stoma haggling with the d rs. Somehow a. misunderstanding arose. Both cezvawshtchiks claimed me, and turned on each other with a fierce tor- rent of invective. I stood helpless, not knowing what to de. In a moment, to my horror, I saw a policeman approaching. Might I not have unconsciously broken some inexorable law or city ordinance? But, . as the policeman drew leisurely manner meant not dignity but indifference. Tho two eezvawschtchiks greeted him with a hower of 1 exclamuations. He _be- n talking back, and soon it was evident that he, too, had become involved in the misunderstanding. A genuine three-handed row ensued. And, to my intense amaze- ment. those two drivers stood there on the ky Prospect, almost under the shadow royal palace, and actually shook 8 in that policeman’s face! And latter started to lead one of the droschkies off the crossing, tho driver krrocked t spatehed the re vehicle around. and ck exactly where he was before, and began abusing the policeman a !’And can you imag- ine what that policeman did? He simply stood there, and talked back! After awhile, when all three had talked themselves out of breath, they placidly separated and each went his own way, as if nothing had happened. I got in a third droschky, whose driver had been serenely sleeping through the whole row, and drove quietly away, the policeman having neve even looked at me! S$ arm away, turned his ‘This was my introduction to the Russian police; and “in my subsequent travels through the czar’s land I learned how characteristically it represented the rela- tons of the government with its people and with foreigners. Pleasant for Strangers. Instead of everything being made dis- agreeable for visitors, the very reverse !s true. Strangers who do rot speak Russian are looked after almost as if they were charges of the government. At the request of their minister, the railway department will reserve, compartments on the trains for them,+telegraph ahead for sleeping berths, give them general letters of intro- duction. and, in fact, do everything it is possible to do. Instead -of trying to conceal the condi- tions that exist in Russia, the government tries to reveal them as plainly and fuily as possible. For instance, during the progress of the exposition at Nijnt Novgorod in 1898. the goverrment gave to all foreign news- paper corresponderts free passes, good for first-class passage over all the railroads in the empire. On such a pass I traveled not only through European Russia, but also through Sileria—peaceful, contented, mis- represented Siberia, As for police surveillance of foreigners, I found absolutely none of it. My trip of 100 miles was made without letters of in- treduction or any other documents of any sort, except my passport, and it really told nething about me of value. I was in places where probably but two or three Ameri- cans had ever been before, and I carried a czmera, took phctographs freely and in- vestigated everything I saw. Yet no per- son, either offi or private, apparently ever regarded me with anything but sim- ple curiosity. But what are the government's relations with nihilists? you will ask. Briefly, the situation seems to be this: The “nihilists’’ proper are opposed to all law, order and right. Today there are probably few, if any, real nihilists in Russia. But there aro and have been revolutionists, and these revolutionists have included many terror- ists, men who claim, ‘as stated in one of thelr official papers, that they are “morally justified in making use of all attainable methods of procedure;” that is, that there are no means that (tt ir ends do not jus- tity. b Against Terforists. Against these terrorists the severest measures have necessarily had to be taken by the government. And there is no doubt that this severity thas at times been in- nocently directed agairfist liberal-minded people who were not terrorists, just as in this country men have been hanged for murders they never committed. As to the treatment of the Siberian ex- iles I may here say only this much: All of the bad features of:this system have been described in detail, while-many of the good points have never even, been mentioned. And of the bad fedturcs,'at least one-half or three-quarters are“dué to the naturally dirty and bestial conditions under which the Russian peasant habitually and yolun- tarily lives. These conditions will be appar- ent to any one who Will associate inti- mately with the peasanté: But by far the most‘important feature of the nihilist and revolutionary movement in Russia is its comparative insignificance. And the most striking thing in the arbi- trary treatment by the government of po- litical prisoners is the absurdly small num- ber of such prisoners. Mr. Kennan has given us a very vivid picture of the condi- tion of the Siberian exiles. But it is a pic- ture that, according to Mr. Kennan's own figures, represents an: almost infinitesimal part of the whole Russian pommecien- The total number of exiles, voluntary snd in- voluntary, that go to Siferia annually has never been over 18,000. (See official figures in Mr. Kennan’s “Siberia and the Exile System.”) And of these 18,000 the number of political exiles of all classes is estimated by Mr. Kennan as only about 150, eae over one-eight b cent of nearly everything we have read of Russia has been written about a class of people whose whole number is certainly not cver one four-hundredth of one per cent of the whole population. How the government treats the other ninety-nine and three hundred and ninety-nine four-hundredths per cent cf her people we have not been told. The Revolutionary Movement. But even this small number of political exiles is rapidly decreasing, and it may be safely said that today the revolutionary movement in Russia amounts to practically nothing. There are many reasons for this. In the first place, the government is really sincere in its desire to allow the greatest possible freedom of thought and expres- sion consistent with the integrity of the government and of law and order. In the second place, the administration of the laws is becoming more and more efficient, and the government is more able to carry out its desires and to prevent their per- version by corrupt officials. Cases are abundant to prove the really liberal aims of the government. For in- stance, there is the history of the scientist Potaneene. Some time ago he was exiled under easy conditions to eastern Turke- stan. There he spent his time in study, did valuable scientific werk, and soon con- vinced the government that he was not dangerous to its welfare. Whereupon he was made a member of the Royal Geo- graphical Society of Russia, and was sent by the government itself at the head of scientific expeditions to the Turkestan country, and he is now living and working in St. Petersburg, in the highest esteem of the government. Then there is Tolstoi. His writings are not allowed to circulate in Russia, but the government knows that the man himself is thoroughly loyal, and he lives near Mos- cow, doing as he pleases and writing freely. How little is left of what little nihilism and terrorism ever existed in Russia may be shown in many ways. For instance, some years ago the emperor attended the launching of some war vessels at Odessa. On his arrival in the city the crowds sur- rounded his carriage, took the horses out of the harness, and, shouting and cheering, drew the carriage themselves! As for the present czar, he goes everywhere w ed. ‘And more significant than thi fact:that it is his regular custom to drive out every afternoon in the winter at the same hour with the empress. There is but littie to prevent his assassination on any one of these occasions Chief Obstacle to the Movement. But the greatest obstecle to the success of the revolutionary movement in Russia is the people themselves. Strange as this statement may seem, it is literally and unqualifiedly true. About 90 per cent of the Russian popula- tion are peasants (mouzhiks), and it is these peasants who make Russia what 1 is. Now the condition of this great mass 01 people is very peculiar. Thirty-five year: ago they were practically slaves, bound tc the land and bound to the master of tn lard. In 1862 the government freed ther completely, just as our slaves were freed But the Russian gcvernment did not sto} here. From each serf's former master i bought a certain amcunt of land anc provided practically every peasant i: the lang with a home of his ow While the material condition of the peas- ant has been so much impreved, he him has advanved but tittle. Today the grea mass of the Russian people live under con ditions that the poorest class of our pop- ulation would deem intolerable. The mouz Lik’s daily diet is tea, black bread an¢ soup; he lives in a two-rocm log house and he and all his family sleep on the hard wooden floors in their ordinary clothes He wears a few cheap cotton clothes the year round, and jn winter simply adds a huge ceat, made of undressed sheepskiz He works ten to fourteen hours a ¢ cheerfully, but often will work only thr. or four days in a week, as this is enough to suppert him. He is obedient, unambi- tious and contented in the extreme. A people like this, thoroughly illiterate, ignorant, lazy and improvident, cannot be transferred from a state of complete de- pendence to one of complete independence without some assis A this guidance ssistance the Rus: governr ys furnished its peo- ple. ae ay be stated without the ightest fear of successful contradiction that mo! the Rus directly fe rnment has its people thi done any other government in the world. Protecting the Workers. Take first the city workmen. For the welfare of these the government has estab- lished complete and minute regulations. Every factory is under immediate govern- ment supervision. Its rules must be ap- proyed by the government in every detail. The number of werking hours in a day allowance for mea! hours, the a which children may become emplo: time and manner of paying wage the factory houses and fe the condition of the house: government. Education is looked after by compelling all children to attend school for a certain time. It is the same way in the country. There the peasants are helped, guided and re- strained by the omnipresent government. In famine time it is the government that feeds the people and keeps them from star- vation caused by their own improvidence. In the great famine of a few years ago the ezar gave half of his whole personal in- come for the relief of the destitute peas- ants, the most of whom could, if they pleased, make in any one year almost enough to support themselves for two years. Where the old system of cultivation is inadequate the government introduces and maintains new methods until the peasants have learned them. In eastern Siberia, where salt is scarce and stock raising is very important, the government supplies salt free to the in- habitants. In order that the peasant may travel around and work in the cities in winter, when his farm is covered with months of snow, the government has made third- class railway fares so low that a man can go from Warsaw to the Siberian frontier, over 2,000 miles, for $8.60, or ‘about two- fifths of a cent a mile. And nearly every Russian mouzhik has received the educa- ils benefit that comes from this travel- ing. Compulsory Education, In education the government does as much for the farmer as it is now possible to do. Schools are universal, and attend-" ance, I am informed, is compulsory, just as in the cities. There are also in the cities the most important kind of schools for Russia—namely, technical schools. These “are free to everybody and may be attended by students from the country as well as from the city. And to make at- terdance at these schools practicable for the poor the government provides all stn- dents with free railway passes to the schools and back to their homes. During the recent exposition at Nijni Novgorod the government also gave a pass to every- body that wanted to go to the exposition for study and who could not afford the rail- way fare. There is one institution in Russia, creat- ed for the benefit of the peasants, that Places the czar’s realm in this respect above all the rest of the world. This is free and universal medical attendance. Each zemstvo (or county) has its own med- ical staff and hospital, which are maintain- ed by the government. And any one in the zemstvo who is sick may have, free of cost, the best medical attendance and medicine. Another excellent government institution is the peasant bank. This is found every- where over the country, and its business is to loan peasants money at the lowest pos- sible rate of interest. I was never in a bank in Russia that I did not see among the bank's. patrons one or more tawny- haired, roughly-clad_ mouzhiks. The Village System. Probably the strongest indictment we Lave heard brought against Russia is that the peoplesthemselves have no voiee in their own government. We are told that the peasant really belongs to the govern- ment, that he is not only down-trodden and oppressed, but also that he 1s deprived of all control of his own affairs. This state- ment is absolutely false, and it can be proved to be false by any peasant in the empire. For every village in Russia complete control over its own special hf- fairs, The farmers, let me explain, all live in villages, and cultivate the land around the villages. Now, each village has the power to apportion this land out among tts mem- bers, to say how it chal be | the means to enforce it. Thus, any mem- ber of the village who is persistently de- linquent in paying his taxes or in doing his Part in the common work, or is an unde- sirable citizen generally, is expelled from the villag> and sent to Siberia. And, as a matter of fact, 40 per cent of all the pris- oners sent to Siberia are sent by the vil- lages. It is hard to imagine a community hav- ing more complete control over its own a fairs than is possessed by the Russian v! lage. We can now see why. revolution has failed so completely in Russia. No political agitators have ever been successful in get- ting the peasants to tura against the gov- ernment that docs so much for them. And today it would be hard to find a more loy recple than the Russian. Aside from thi the peasants them: are so lazy, so un- ambitious in every way, so i nt to everything except the material comfort which they can so easily provi them- selves, and so thoroughly cont that it would be practically impossible to get them ever even to desire a revolution. The truth is that the Russian govern- ment lets its people do themselves everything they are competent to do, and does for them everything they cannot do. ‘The villages have had some control of their ffairs for centuries, and are thus able ef- fectively to maintain this form of self- government. But other forms of self-gov- ernment the peasants are now utteriy un- fit for; and no parent who allows his chiid to do~anything it pleases. of its welfare, is any more foolish or sinful than would be the Russian government to a its people to do anything they please. short, what Russia needs today ts “no’ revolution, but evolution,” and the Kov- errment that can and will. best promote the progress of this evolution is the gov- ernment now ex ‘ing. —_ ART AND ARTISTS. The collection of original drawings and paintings displayed at the Cosmos Club w: kK, the most notable exhibition held this we and the work skown made the forward strides which modern illustration is taxing very manifest. A great many students visited the exhibition, and those fitting themscelve for that branch of art wers able to learn much by comparing the origi- nals with the proofs, snowing the work as it appears after reduction for illustration purposes. The drawings, which number more than a hundred, and which bear < signatures of sevente>n different art were made for Scribner's Magazine as il- lustrations for Senator Lodge’s Story of the Revolution and Capt. A. T. Mahan’s ar- ticles on the American Navy in the Revo- lution. To consider Howard Pyl2’s pictures merely as illustrations would be doing them scant justice, as they are executed ix fuil color, and from their masterly com- position, fine action and careful attention to historic detail, d: to take tank with the best war pa “Retreat of at- In the delineation of battles and es of spirited action ths young mparatively obscure illustrator, F. ability, and aittl tings. from Trenton” is especially worth: tention. A. Shipi known, shows gr noth young artist who dan the collection is Ernest Peixotto, who, in cape and architectural subjec' $ a combination of pen and we 'y effective results. His use of dots and short lines in pen and ink work makes his style peculiarly his own, and his technique suggests th? influence of no other illus- taator, with the possible excepiicn of Vierge. Mr. Peixotto’s sketches of the cit- adel at Quebec, the Old North Courch in Boston and of Independence Hall in Phila- delphia are drawings that one iikes to lirger over, * * studies by Elizat th The sketches and Nourse, which were shown at Fische this week, reveal a new side to her wi and in a number of water colors proves her ability to handle that medium as well as oil, With the exception of a few Dutch scenes cnd flower subjects the etches were all made during her recenc stay in Tunis, where she found aa endless zmount of picturesque material su'ted to her brush. The street scenes bring the celor and atmosphere of the city vividly before the eye, and the interior with the two native women weaving gives a sght into the daily life of the in’ Of even more interest than her water col- ors are the many small study head cil which Miss Nourse made of the ous types to be seen in Tunis, and in the: heads she has shown an unusual talent for eapressing character in few telling strokes. Her flower studies, executed in gouache on tinted paper, are also well worthy of notice, as one seldom sees flow- ers massed in such a bold, unconventional wey. * * ok Among the Lenten lectures to be given this year is an illustrated course on art topics, by Miss Dora Duty Jon whose study in preparation for this work has fit- ter her to give a most satisfactory presen- tation of her subjects. She has gathered together some especially fine illustrations which add greatly to the interest of the course, those for the first lecture, on Botti- celli, given at Mrs. Ffoulke’s on Friday at- ternoon, consisting of a large and unusual- ly complete collection representing his work, * x * The exhibition which the Charcoal Club held on Monday and Tuesday at the club studio was well attended; and the time spent in a short visit was well repaid. The werk exhibited was all by students, and very naturally showed a lack of advanced knowledge, but it is always interesting to notice in the work of the student the ten- dencies which may govern the career of the artist. In some cf the studies one could see the germ of an idea which the worker had not the experience to carry out satis- factorily, but most of the members of the club have reached the point where they can express their meaning with a fair amount of artistic skill. Carl Heber, who is the president of the organization, showed the only works in sculpture, and of his contributions the baby’s head and the little pickanniny entitled “An Alabama Blos- som,” were especially admired. Perhaps the most original thing in color was the atmospheric early morning sketch by George Parson, who also showed strong work in black and white. H. Rt. Jehnson exhibited some attractive specimens of burnt wood decoration, and Messrs. Bai- tour Kerr, Harry Kerr, R. E. Renaud, Fitzpatrick and Totten were among the other club members who showed pleasing work in pen and pencil. * = In Miss Katherine Chipman’s water color portrait of Mrs. Donald McLean, which is now on exhibition at the Corcoran Art Gal- lery, the modeling of the head is very care- fully studied, and the strength of color is such that the portrait holds its own among the oil paintings that surround it. Miss Chipman has chosen a profile view, and has concentrated her attention upon the head, giving merely a suggestion of the low-cut gown. Mrs. McLean's friends unite in considering it a good likeness, and to one unacquainted with her the face is full of character, and a certain dignity of bearing is easily discernible. In Miss Chipman's studio, in the Cairo, is a likeness of an- other woman prominent in the D. A. R., Miss Mary Van Buren Vanderpool of New York. A very good example of what the artist can do when working with a dark background and a rich scheme of color, is the solidly painted head of a frank, pleas- ant-faced boy, and a number of other in- in the city for several weeks longer. ES * x At the studio of Prince Troubetzkoy, in the Corcoran building, he has a couple of portraits quite well advanced. One is a well. In this line, and more especially in painting street scenes and views of chy life, he has a great aptitude, as is shown by « mimber of his paintings of this sort which were exhibited at Fischer's, **s A portrait by William T. Mathews, whose name is familiar to the Washington public through his well-known full-length portrait of Abraham Lincoln, exhibited at the Cor- coran Art Gallery, is now on view at Veer- hoff's. It is a likeness of the late Mi Emma Troll of Canton, Ohio, and the artist has given great atte to the little touches which give life and expression to a portrait. In fact, throughout every part of the painting one finds a refinement of the z ails rather than any broad generaliza- jon. ‘i to the permanent ‘inter exhibition at the gallery of the y of Washington artists are a fish y Jules Dieudenne and a careful and Study by Edward Siepert of the at Bladensburg, very sunny in ef- = x * ses placed on view allery are two excellent Dutch Mr. R. N. Brooke. The fine of color which the public has been ht to exrect in his work is present in a rked degree, and the paintings are fuil of artistic feeling. Mr. Messer has on ex- hébition a very subtle early morning sub- jcet, showing a flock of geese Straggiing down through the dewy grass to the brook in the foreground. George ¢ by picture avality tauj bbs is repre- scnted by two previously exhibited oils, a marine view and the well-studied figura called “The Student.” Another marine shown there bears the signature of Frank Mass, and there are several waier colors fromm Walter Paris’ brush. Another of the new canvases is James G. Tyler's truthfully painted picture showing a full-rigged yacht by moonlight. i * x * It will be of interest to many to note that Frederick Remington was here in the early art of the week, making sketches over at Fert Myer of the sert so widely associated with his own peculiar genius, * * * Mr. E. L. Morse has just about finished & portrait of Justice Shiras in his robes. It shows the head aad shoulders against @ background of dull, rich red, which, in con- trast with the black gown, makes an ex- tremely pleasing color effect. Mr. Morse cceeded in making an excellent like- ness, bringing out all the Strength of the well-marked and dignified features of the justice. His simple treatment of the gown is alse very good. * : x Miss Bertha Perrie left on Tues New York, w! Whitney's gw spend a week many exhi the metropol ay for re she will be Mrs. Josepha st. Miss Perrle expects to or so in the enjoyment of the «ns and other art events of * * Mr. Edwin Lamasure’. tion of water colors cl Veerhoft's and it will be tolowed by an exe hibition of paintings by David Walkley. Two notable pictures which were at tho wcrld's fair will next be shown in the gal- lery. Both of them are by Polish artists, the first, which is by K. Alchimowicz, is en. titied “Glinski in Prison,” and the second. which is by Malczewski, portrays the death of an exiled woman in Siberia. x * Carlton T. Chapman expects Washington a visit about E will display a Veerhott’s. pleasing exhibi- SCS this week at to pay aster, and he collection of his paintings at —>—_ A PATHETIC sToRY, Recalling the Uistory House of Sir Walter 5S. ma Ixndon Paper. The recent marriage of Miss Ma ephine Maxweil-Seott in England recalis to a wriier in the Sketch the story of the house of Sir Waiter Scott, which is one of th ost pathetic In the whole range of mily building. Miss Maxwel ott great-great-granddaughter of Sir Walter, and her alliance to Mr. Alexander Dal- gleish is the first that the ereat-great- grandchildren of the poet have mad The writer referred to sa it was otUs dearest wish to found a house which should carry on the traditions of his great a..cestors, who were cadets of the Scotts of Harden, now represented by Baron Polwarth, Scott reared Abbotsford at enormous cost, but here his work began and ended. His eldest son, who succeeded to the baronetcy, survived him oniy fifteen years, aad died in 1847, unmarried, at the Cape. And so the baronetcy became ex- tinct. His second son died at far-off Te- heran, also unmarried. So the name of Scott was left to his daughter Charlotte, who married Lockhart, the biographer cf Sir Walter. Her son, Walter Scott Lockhart, adopted the namé of Scott, but, with all the extraordinary fatality that had overcome his uncles, he, too, died unmarried at the age of twenty- six, and so the estate passed to his sister Charlotte, who married J. R. Hope, Q. C a memter of the Hopetoun family, and he, of course, adopted the name of Scott. They had three children, but their only son died in chiidhood, and once again a woman came to rule. This was Mary Monica, In 1874 she married the Hon. Joseph Con stabie-, Well (third son of Lord Herries), who, as a matter of course, adopted the name of Scott. They have had six chil- dren, the eldest of whom, Waiter Joseph Maxwell-Scott, born in 1875, is in the army, He has two brothers and two sisters livin, Mary Jesephine, who was married recently, as born in 1876. Thus it will be seen that the preseni generation of Scotts have been in turn Lockharts, Hopes and Maxwells. These are all excellent names, with honor- able histories behind them, and yet, in strict genealogical sequence, the present generation, to waich the bride of today be- jongs, is very far removed from the author of “Waverly.” By a curious coincidence, Scott's biog- rapher is recalled at this moment, for John Gibson Lockhart’s nephew has become commander-in-chief of the forces in India. This is Sir William Stephen Alexander Lockhart, K. C. B., K. C. 8. L, who suc- ceeded Sir George White the other day. Sir William's father, the Rev. Lawrence Lock- hart, was the half-brother of John Gibson Lockbart. The general, who was born in 1841, began his military career with the Sth Fusiliers in Oude. He has served in ten campaigns in India, most notably the Black Mountain expedition and the Aighan campaign of 1879-80, when he was present in the operations round Kabul. He was given a brigade in the Burmese war of! 1886-87, and has since been engaged in sev- eral frontier wars, just as his ancestors probably used to figure in the raids which characterized the Scottish border in days of old. is a - Soak's progress: (1) A man with & thirst. (2) A thirst with a man. (3) A thirst. @ Snakes.—Life.