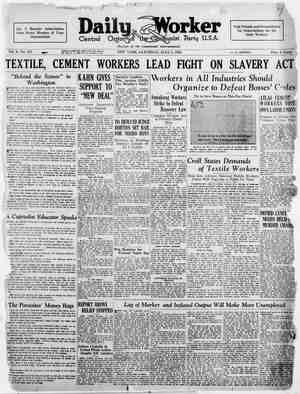

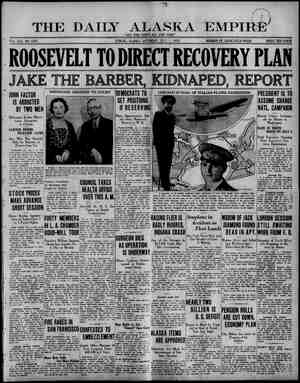

The Daily Worker Newspaper, July 1, 1933, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

WORKER, N DAILY iW YORK, SATURDAY. JULY 1, 1938 ' “My:iSon Was Convicted Because He is Black,” (The following’ is an open letter writt8n by Cidude’ Patterson, father pub- of Haywood Patierson, and lished in a recent tanvoga, Tenn‘ newsyaper): Haywood Pat- naturally, in- down in Ala- in which you ex- sh that the Inter- Defense, Labor from all connection withdraw thissoake. cirn I would appreciate giving you and the public r valuable of this case, that will things and to correc! evropeaus impressions about this ca ‘ e started, and arrested and had made no wit- no -employed attorney, and prced-4nie—trial unprepared ; a combination of cir. tances, the public greatly by the: false testimony in- sced on, that trial ARRESEE At “that “4imé the trouble -oc- curred, a crew of white boys at- tacked a nun of colored boys. threw rocks at,.them, and provoked a in a “flab car on a long train of about’'50° cars, with nine fiat ears in grow; this fight was in flat car mynber four counting from the reat*end of the train and the o women were in flat five one ear aheag ofthe fight. ver and the When the fig) t ~ juimpe f except one man named Gilley, he was trying to swing off, but he w about to be Rifléd uritiar ‘the car wheels and Haywood Patterson, Andy Wright and Charley Weems pulled him back up on the train and let him remeabr there, hen the frein reached Paint seni 1o arr: that train, because of this fight. After they sgere;taken to Scotts- boro, the rep pread that. they had been accusedsof assaulting the two white wi flat it Tront 8G, “This¥'report only be started, and the ‘Tints ar he Jackson nel jouw) do the rest white lO” batch of Ties was"ever writien or nennegdgby the hand of man, fav the batdh oftlies Sent out from Scottsboro about these innocent bovs and if you will bear with me, I “fl! tell you about it. In Jer to make the women | sweat lies and stick to_it.they.were beth, locked Sup in the same jail “the wffite boys and Colored varate,cells, but why put women fr jail? Put in there to ld them in line and make them es, So Ruby Bates has said. put those seven white boys Put them in jail to make n swear lies,+so Lester Carter s but not one of the white boys ever testified “gninst my son, Hay- wood PatterzorG Orville Gilley was put in jail but he refused to tes- tify egainst Haywood Patterson, in Scottskoro, ary# ‘ail the white boys were released and not one of them ever testifictk iy~any case against Haywood Patterson. Did they see a crime committed? No, sir. Well, why were they)-kept in jail at Scottsboro? They told my son and these other boys thet it was a frame-up lie and-they \ 1%" net) going to testify to such a batch of lies as that was, and they did-not—testify to it. Not one ef the--wiktite- boys ever took the: witness=stamd=against my boy. they were convicts, and while that mock trial was go- ing on, the International Labor De- fense had a man from New York sitting in the.audience who re- ported-‘that 4é7 was the greatest mock trial ever held in the State of Alabama. This case was held when I was afraid to go to Scotts- boro, for fear of mob violence, and I employed.:George W. Chamlee, attorney, of Chattanooga, Tenn., to represent my son, as he had been my lawyer befere-that time. Just at that. time:Mr. Brodsky of the International. Labor Defense, and its chitf couhg?l, from New York, came to Chattanooga, and said he would help me pay the expenses of this’ ‘dase ofan ‘appeal, and the appeal was taken, and a new trial granted in the Supreme Court at Washington and the expenses of orintiny th€t jecord was about $1,500 alone. °° ‘F it had not been for the Inter- national Labor “Defense coming to our assistance, quickly, in time to file a motion. for a new trial and set up.a realyedefense, the boys would all have-been killed, although they were all.iunacent. Ty one of _y editorials. you suggested tits , we needed was some good Southern attorneys, like Mr. idy and Mr. Moody and the boys would have a chance to be acquitted. ee Well, Judge Hawkins had them, while the trjalyin his court was on, one when the State’s Attorney got up-and Shook his finger in the faces of these »boys, denounced them, demanded, the death pen- alty fdt'them, ‘HO’ attorney got up and offered one: word of argument, or any ‘summation, on behalf of these nine bdys, “and then a second attorney for the state demanded the death penalty, and Mr. Roddy and pins Moody Meclined to argue the Ci ‘WE HAD A TRIAL, RECENTLY” We had a trial at Decatur re- cently and tl had one star witness, V ‘ice, an under- world character, who had been con- victed in the courts of Huntsville for vagfancy.“ewéness and violat- ing the prohibition law; she had broken up the family of Jack Tiller, «° Writes Father of correspondents, and | 2 news was carried | boys saw the | So about it, | “ITE LAW IS TOO SLOW’—From a book of Lithographs by George Bellows. and Tiller’s wife had to take her children and leave him; this woman swore she spent the night house on 7th St. in Chattanooga, | while Ruby Bates, and E. L. Lewis and Dallas Ramsay rSawd By RALPH GARRETTE HE judge said that he was not guilty, but he must die. So John Williams, a Negro worker of Perry, Florida, was burned alive in 1928 by the Klu Klux Klan. John Wil- liams, twenty-year-old Negro work- had been framed up on a cl of murdering Miss Hunter, a white woman school teacher. | At the time the murder was com- Alabeipa, gy order had been | c* the Negroes on | mitted this Negro was working in | | a saw-mill five miles out of town | The murderer’ who killed this | woman, the police never did find. The cops went around in different sections of the city, beating Negro workers, carrying them to the po- lice station, trying to make the Negro Workers say they had done the killing. There were over 100 | Negro workers beaten up. The same night that Williams was arrested he was carried out in the farming section of the country. The cops told him that they were going to tun him over to the mob if he did not say that he had killed the teacher. He told the cops that when that killing was done he was working, and he had proof that he was working, The cops told him, “Damn your witness and you too! We are going to kill you for the killing of the teacher.’ Williams was dragged to the police station and locked up. There was a mob of 10,00C looking for this worker, going in different sections of the city, burning down the homes of Negro workers and churches, look- ing for someone that killed the | teacher. But they did not find the murderer. HE killing was done in July. This worker was killed in August. He was tried and all the evidence | proved that he was innocent. But the jury said that he was guilty of first degree murder.. A mob of 10,000 took this worker out of jail and carried him five blocks from the courthouse beside the rmm- road, where there was an iron stake in the ground. This mob took shovels and dug a five-foot trench around the iron stake. The Negro worker was tied to the stake, with his feet tied together and his hands behind him. White bosses came from different counties to see this Negro worker burned alive, The mob poured five gallons of gas- oline on the wood which was piled around the Negro. This worker was crying, “Please turn me loose. I don’t know nothing about it. O Lord, save me!” Some members of the mob said, “The judge said you must die, and we are going to do it.” Someone | asked the Negro if he had some- thing to say before he died. He said, “I want a cigarette.” One of the members of the mob said, “I'll at Mrs. Callie Broochie’s boarding | Lester Carter | all swore she spent the night in the woods on the bank of Chattanooga creek. On her testimony, prac- tically alone with no witness to the facts, and her evidence contra- dicted by five Colored boys, in addi- tion to other impeaching items t Myself give you the cigarette — and the light.” They gave him the smoke and loosed one of his hands so that he could light the cigarette. When he. lit the cigarette, that. started the fire. This Negro worker prayed, he called on the Lord. The mob laughed at the Negro worker and said, “Shut up, you black son of a bitch!” : His body was burned into ashes. The mob scattered away. The next day the bosses’ newspapers stated that an unknown mob had staked John. Williams and burned him alive, but the state of Florida would do everything in its power to arrest every member of the mob and punish them for the murdering of John Williams.. But the state of Florida did not do anything to stop the mob. If they wanted to stop the mob, why didn’t they stop it at the first? Not only the state of Florida, but all other states of the country are carrying on a cam~ paign of lynching Negroes, legal and otherwise. Bill Dunne Writes on “New Deal” in June New Masses, Just Out Wm. F. Dunne, writes on “Three Months of the New Deal” in the June number of the New Masses, out today. It is an issue chockful of live material, more interesting than past year. nalist and editor of “Izvestia,” con- Disarmament Conference called “America in Europe.” The. Revolt of the Children,” by Helen Kay, ed- itor of the New Pioneer (also out today), is an eye-witness account of the “baby strike” in Allentown, Pa. Gertrude Haessler and Marguerite Young contribute brief accounts of the lives of Clara Zetkin and Rose Pastor Stokes, respectively. Huggo Gellert illustrates these articles with drawing of Zetkin and Stokes. A poem and a drawing by Rose Pastor Stokes are also featured. Other features include two stories by Philip ‘Stevenson and Jack Con- roy; “Two Civilizations” a poster by Fred Ellis; “The Royal Wrench and Other Stories,” by Robert Forsythe; “The Authors and Politics,” by Edwin Seaver; and book reviews by Gran- ville Hicks, Nathan Adler, Norman Warren, Philip Sterling and Boris Gamzue. A review of Paul and, Claire Sifton’s play, “1931,” By Eti- enne Karnot, rounds out the issue, which contains drawings by Gropper, Phil Bard, Hy Warsager, Refregier, Theodore Scheel, as well as Gellert and Ellis. Readers are urged not to miss this issue of the “New Masses.” any New Masses published within the | Karl Radek, brilliant Soviet jour- | tributes’ an article on the Geneva | Haywood Patterson against her, a death penalty was | pronounced upon my son. The big lie that Ruby Bates had been bribed. Who bribed her? When and where was she bribed? She has been trying to join the defendants. from the first day she was put in jail in Scottsboro.’ Who | bribed Lester Carter? Where did he get this bribe? Why was Car- ter and Gilley not used on the trial thing material? “MY BOY SAVED GILLEY” My boy pulled Gilley up on the train to keep him from being killed, while attempting to jump off. Was Gilley afraid of him then? Sure not. Dr. Bridges testified that two hours after Victoria Price was ar- rested and put in jail he examined her, that she was not even ner- vous, hysterical, or that there were any serious hurts, only a few scratches, and no injury, and his testimony did not help her case. Other medical testimony proved no crime was committed. Why did the jury convict Hay- | wood Patterson in Alabama when he is absolutely innocent? Be- | cause it was a white woman ac- cusing a Negro boy. If it had been a Negro woman accusing a white boy, he would never have been in- dicted, or if it had been two Ne- gro girls accusing seven white boys and one Negro woman came up has done, that would have been | the end of this litigation. | Haywoo# Patterson was convicted because he is black. No other } reason, no other excuse, no other cause, none wanted, entirely inno- cent. Yours truly, CLAUDE PATTERSON. Book Notes NEW. ISSUE OF INT’L. LITERATURE’ NOW OU THE firs; number of the 1983 series Lf gt InternaHenal PMeratore, hand- tad in the TSA, by Intemnationel Publishers, has fst arrived and fs veady for distribution. The mara- rine which js the ofty one of tts kind ovailehle in the Enelish lancvege chovld rrove of ereat value nartien- Jerly to the evitural movement. ohn Reed Clubs, workers’ clubs and other cultural organizations can use this magazine in connection with their activities. ‘The new number contains many stories, sketches and critical articles. Boris Pilnyak tells about his visit to America and particularly about his experience in Hollywood. Stories and articles by Romain Rolland, Maxim Gorky, Bela™ Iies,~ Louis Aragon, Agnes Smedley, I. Babel, Shklovsky are also included. There are also articles on the Negro poet, Langston Hughes and the proletarian cartoon- ist, Fred Ellis, both of whom are now in the Soviet Union. It is an issue rich in vital literary material, 160 pages, many illustra- tons, 35¢ a copy. Unlike other periodical publica- tions, International Literature cannot be looked upon as getting out of date —when new issues appear. There are still available a number of copies of Number 1 and Number 2-3 (1932). aes . BOOK OFFERS FOR ALL SUBSCRIBERS | Elsewhere in this paper, is an ad- | vertisement informing you that you can get several valuable, instructive and entertaining books for only 50 cents by subscribing for the Daily | Worker for six months. “Memoirs of a Bolshevik,” by O. | Piatnitsky; “Forced Labor in the | United States” by Walter Wilson, | with an introduction by Theodore | Dreiser; “Soviet River” by Leonid Leonev, with a preface by Maxim Gorki; and “Jews Without Money” by Michael Gold—these are the titles. | Every one of them deserves a place in every workers’ library, Ordinarily you would have to pay from $1 to $3 for each of them. By taking advantage of our spe- cial offer, you can get the Daily for six months ($3.50) and any one of these books for $4 in all! Our supply of these titles is run- ning low. We suggest, therefore, that you send your $4 for this spe- cial offer without delay! In proportion as the bourgeoisie, ie., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, devel- only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labor increases capital—_Communist Manifesto. in Scottsboro, if they knew any- | confessing her lies, as Ruby Bates | oped—a class of laborers, who live | CLAUDE PATTERSON Muire Miner Tells of Ohio Prison Torture By EDWARD NEWHOUSE N amazing story of a brutal judi- i} ciary and vicious penal system was unfolded yesterday at the office of the Daily Worker by Edward | Smith, a Negro miner recently re- | leased from London Prison Farm, Ohio. | Smith came not to tell his own story but to help a former fellow convict, Ernest Conn, first incar- cerated in 1929 for stealing a pocket knife while drunk and subsequently transferred to the Lima Criminal Insane Asylum. “They didn’t treat Conn worse than the others before he got to associating with me and the other Negroes,” Smith said. “See, the cook there at London, he used to get the Daily Worker off a coal miner on the outside and he'd pass it on to me and I'd read it in the Negro dormitory and give it to Conn after. Sometimes we read it together. Well, first the Captain and the deputies, even stoolpigeons, start riding him, calling him ‘nig- gerlover’ and all that but Conn, he don’t give a damn. Watched by Stool Pigeons “Then they set a couple of the didn’t get a moment of peace. See, one of these stools, Deewester by name, he was the worst kind of de- generate, Conn certainly had his hands full just keeping away from him. And all the dirtiest work they could find and all the worst punish- ments, Conn’d get them. Christ, he was in the hole practically half the time, that’s solitary on bread and water. of sending before the Nut Board every once so often.’ Conn'd be kept in the Idle House for a couple of weeks, that alone’s enough to drive you crazy but just before him some kind of medicine that make him dopey like. Then they'd with questions for any length of stools to testify that he crawls un- der the bea nights and keeps hol- lering for his mother, Couple of times they tried to get me and some others to testify but we wouldn't. | that. “No Kid Gloves” had him up to that Nut Board six or seven times before the transfer. ‘They didn’t treat me with no kid gloves but honest I don't see how that boy stood it. You wouldn't believe half the things I was to tell you. And him only nineteen. “Finally, this February they tell him to get ready, he’s free. And right from the beginning this smelt fishy because his name wasn't either on the bulletin list or The Colum bus Citizen. Now I know they just told us he’s getting off because all the men knew Conn was sane and the Captain knew we could make trouble right there in prison. So when Conn leaves he says, ‘Smitty, when you get-out just go to my sister in Taylor, Kentucky and tell her about this and maybe she can do something.’ I tried to tell him he was getting off alright but he knew it'd be Lima for him, the nuthouse, you know. Served Four Years “I got my reléase June 15, just two weeks ago. I done four years, two months and seventeen days, for taking twenty dollars worth of plumbing tools so’s I could get a job. I'd been sick with a fistula the size of an organize, and I sup- pose the Captain figured I wasn’t much good for work anyhow. “First thing I hit it for Taylor, Kentucky, to this sister of Conn’s, Mrs. H, P. Warner by name. She and her husband had a shack in Taylor there but they certainly | didn’t look as they could afford any | “Then Captain Jack got this idea | he'd go up to the board they'd give | was just like whiskey and it would | have him strip and just drill him | time and they got a couple of these | |" FREES stools on his trail an’ after that he | | That boy never done nothing like | | “Say, in those three years they | | night. By MICHAEL GOLD HE morning was spent unwind- ing the yards of red tape that are woven into the steel chains of a prison. The four I. W. W. pris- oners were checked through several | offices, the warden spoke to them a moment or two, then they turned in their gray prison clothes and re- ceived in exchange their own for- gotten creased clothes, stale after five years’ repose in a bag. Then they were searched twice? for S traband letters, then they were given their railroad tickets to Chi- cago, the city where they had been tried : “So long. boys,” one of the guards at the last steel door lead- ing to the world said joyfully to them.’ He was a tall, portly, serene Irishman, with gray walrus mous- tache, and he had been hundreds of released men stand blinking like these four in the strange sunlight, dazed as if they had been fetched from the bottom of the sea. “So long, bo; drop in again some time when you're lonesome; we enjoyed your visit.” AFTER FIVE YEARS OF DARKNESS The men smiled awkwardly at him, stiffly and with the show of prison deference to a guard. They were still deferential and cautious, like prisoners; in their minds they were not yet free. They walked silently down the flat, dusty road leading from the peni‘entiary to the highroad, their jews set, their pale faces appear- ing unfamiliar and haggard to each other as their eyes glanced from side to side. “So this is America!” said little Blackie Doan, heaving a deep sigh and spitting hard and far into the road to display his nonchalance. Blackie was more nervous and trembling inside than any of the other men; but he could never forget that a gentleman swaggers | and grins and spits with a tough air wh/n he is in a difficult situa- tion. This blow of suden treeom and sunlight after five years in prison fell harder upon Blackie than upon the other men. He had just come, the day before, from 5 months of solitary confinement in | « black, damp underground ceil, where he had been expiating the worst of prison offenses. He had battered with fists and feet a guard more than half a foot his height for the reason that his guard had been beating with fist and black- jack and keys a weak, half-witted boy of nineteen who never seemed to remember his place in the line — another enormous prison | crime. | “The land of the free and the home of the brave!” John Brown, a tall, lanky Englishman, with gray | hair, hawk nose, and steady blue eyes, added monotonously, as in a fi ‘Wish I had a chew of | | | | | : | HE other two I. W. W. prisoners | | | just released after their, five | years’ pynishment for the crime of having opposed a world war did | not say a word, but stumbled along dumbly, as if waiting for some- thing more interesting to happen. One was Hill Jones, a husky young western American, with the face | and physique of a@ college football | player, and with large luminous green eyes that stared at the world like those of an unspoiled child's. ‘The other I. W. W. was Ramon Gonzales, a young, slim, dark anything like a lawyer. Warner's a carpenter by trade but he ain't | been working over a year. | “So I got to talking to her and | she told me she’d been at Lima and | talked to Ernest and there wasn’t nothing the matter with him and she tried to tell them officials but they showed her this paper about the kid calling for his mother at Treated her pretty rough too. Cattle-Car to New York “Poor folks like that can’t do nothing so that’s why I’m here. I | grabbed the first freight out and | rode to New York hotshot. Got off | a cattle car this morning.” He fumbled around and drew out | a packet of paper, soaked to a pulp. | “Couldn't get inside of that cattle | car,” he explained, “Had to ride on top.” | We began separating the papers | to look for a number of addresses. | They were sheets of wrapping paper written closely in a fine hand with occasional drawings of test tubes and Bunsen burners. “One guy there was a chemist,” | he said, “and he’d give me lessons | and have me write up experiments, | I used to sneak him the Daily | Worker before they caught wise.” Smith is going back to his home, town, Jeannette, Pa., where he will | look for work in the mines. His | evidence had been submitted to the | International Labor Defense, which | is -investigating the case. Mexican peons who build roads of our western cour “Wish I had of t repeated Brown, licki with his tongue, a brown drab pra “Feel as if I comida spit cottor The truth was, he wanted the tobacco to steady his ni Ke the others, he was quivering with a rout of weird emo- He had lived for five yi steel house, behind steel bars, im a routine that was enforced by men with blackjacks and shotguns, and that was inhuman and perfect us steel. Now he was free. No one sweet le with his | to was watching him; he was stroll- | ing down a hot country road, under the immense yellow sky. He was pack in the world of free men and iree women; and he, and the uthers. with him, should have preathed deeply, kissed the earth und rejoiced; instead they seemed vense and worried, a little disap- pointed. | a REAL WORLD They all What had they expected? could not have said, but like prisoners, they had built up, w’ vut knowing it, fantastic and ex aggerated notions of the world uutside. It seemed a little o: nary to.them now. The sky dun yellowish waste with a's shining through it. The wide dull prairie stretched on every hand | them. tike the floor of some empty barn, | with shocks of gray rattling corn stacked in dreary rows, file after file to the horizon. A dog was parking somewhere. Smoke was rising from a score of farm-houses, und they heard the whistle of a distant freight train, There was a dull burning silence on everything, the silence ofthe sun. The world | of freedom seemed dull; but pris- ons are tense with sleepless emo- vions of hope and fear. HEY were passing a farmer in a flannel shirt, plodding. behind a ‘team of huge horses in # field of stubble. His lean, brown face was covered with sweat and fixed in grim, unsmiling lines as he held down the bucking plow and left a path of rich black soil behind him “Looks like a in for life, doesn’t he?” said Brown, pointing guy to him with his thumb. “Looks like | that murderer cell-mate of yours, doesn’t he, Ramon?” The little Mexican cast a swift worried glance with his black eyes at the man behind the plow “Yes,” he said shar} and stared back at. the road behind his feet They were moving on to fresh sights in this new world they had peen thrust into—they. were staring at the bend in the highroad where the town street. began, two miles away from -the prison. The ugly trame houses of the middle t set and smooth 1: . the , the stone pavements, then the res and shop windows when the; me nearer the heart of the town—that was what they saw. Up and down the streets men and women walked in the hum- drum routine of life. A grocer was weighing out sugar in a dark win- dow. They passed the little shop of an Italian cobbler. They passed a white school building, from which came the sound of fresh young voices singing. There was a line of | Fords standing at the curb near the railroad depot. where were more women and men walking | | | | | slowly about the square near the | depot, disg’ssing housework, and the elecf¥i for sheriff and the price of } 2mm and the price of hogs. This wls the world. “No Brass Bands” “I don't see no brass bands out to meet us home,” said Blackie, with his irrepressible grin. account for that, Hill? heard we're coming?” Ain’t they VICTIMS OF PERSECUTION Scottsboro” case has entered the movies! But don’t get ex- cited. It came in through the back door and in disguise. The pro- ducer, one William Goldburg, thought he would take a double advantage. The Jews are being persecuted in Germany. The papers are full of another persecution in the South. So he produces “Vic- tims of Persecution,” 1n which Hit- ler and Germany are not men- tioned, but whdse chief character, a Jewish judge running for gov- ernor (an orchid for the Leh- mans?), holds out against threats o>— THE SCOTTSBORO CASE IN THE FILM--REVIEWS “Victims of Persecution” Evades Vital Class Issues; “Life of Jimmie Dolan” Is Typical Hollywood Production — OF CURRENT MOVIES and bombs to see that justice ts dealt a Negro charged with arson. ‘The Negro, of course, has to. be an “educated” Negro, of. the “better class,” Unfortunately, the Negro is never presented to us and we don’t see the case fought. There’s a lot of talk in the Judge’s private dwelling, badly staged,acted,apoken. ‘The only Negro the audience sees is the Judge's Negro butier, handled in the usual white man’s manner, clown and loyal servitor, treated like a member of .the household by everyone down to the Jewish cook. She, in turn, is like a daugh- ter to the Judge’s aged father-in- Jaw, who has come from the per- secutions of Europe to New York en route to Palestine. The Judge’s friends seek to hold him from his conscience. Judge and not the mass-pressure _of an I.L.D. that has fought for the Negroes in and out of the courts. The mass-pressure of the Judge’s fat friend almost persuades the Judge to back out. But in steps grandpop, whose eyes have been burned by powder meant for the Judge, and tells them a story of olden Jewry to prove that it does not pay tosacrifice one’s con- science to the welfare of one’s peo- ple. An attractive fragment of an old film is inserted, only it really proves just the opposite. Who cares? It was a way to save money on production. And after all, a penny saved is a penny earned, Persecutions in Germany persecu- tions in America, what are they if not opportunities for the Gold- burgs and the Paramounts and the Morgans and the Rockefellers to You see, it’s the good heart of « make a little money to keep their home fires burning. In 1929 a sim- ilar picture was made by an “in- dependent” with a great many lam- | entations, hand-wringings and eyes on the box office. HARRY ALAN POTAMKIN. “THE LIFE OF JIMMIE DOLAN” Wisp is a type of Hollywood movie that simply defies serious analysis. Adolph Zukor, a well- known film producer, once frankly admitted that it would be bad busi- ness policy indeed to manufacture movies that appeal to anything above an average fourteen-year-old intelligence. One would have to be blessed with a very charitable nature to squeeze “The Life of Jim- mie Dolan” into even this category. Under normal conditions I would not dare show it to ten-year-olds without prefacing it with blushing apologies from the management. Boys and girls, gather around for another little lesson in our famous Hollywood series entitled Life and Its Realities; This particular les- son is in eight long, seemingly end- less reels and teaches you that there are detectives with hearts so big and kind that they make Mother Machree seem cruel by comparison; that you can get away with it (murder) if only you de- cide to start life all over again and search out the proper farmer's daughter to help you along; that with the proper scenario our hand- some young hero (supposedly weighing 170 and looking like a lightweight) can, with a minimum of training, enter the ring and give a European heavyweight champion the battle of his life for seven rounds at $500 per round, there- with paying the mortgage on the farm; that “idealism” still holds in matters of love and taking care of the weak and disabled, and that city folks can’t milk cows. If you think for one minute that all this sounds rather pointless and crack- brained, then all we can say is that you ought to see the monstrosity itself! Or rather—forgive us! Keep away from it! Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., can smile a little like his famous old man. Loretta Young is still sweet, as saccharine. But don’t let that tempt you. If this review succeeds in keeping a dozen workers from seeing “The Life of Jimmie Dolan” we will feel that our supreme sacrifice in hav- ing had to sit through it shall not have been in vain. SAMUEL BRODY. | ture us, you can keep,us “How do you | BP A SHORT STORY By MICHAEL GOLD |} Hill, the young husky quarterback with the large green eyes, seemed unable to say a word. He scowled at Blackie, it seemed, and shook his head. “What's the matter, Hill?” that y queried, with an insolent grin, “ain’t we as good as they boys who fought to make the world safe ocracy? ut up!” Hill Jones mut- tered, “you get as talkative as @ parrot sometimes!” “I'm an agitator. that’s why T | talk” Blackie jeered and would have | sai more, but that the Englishman Brown put his hand on Blackie’s arm. There was a policeman loiter- ing on the next corner, and for. some strange reason, known only prisoners, the impassive Eng- man was suddenly shaken to lish | his soul. “Let's get some coffee and,” he said, leading them in the door ofa cheap restaurant shaded by a wide brown maple tree. The four sat on stools against a broad counter ded with plates of dessert, and ed into a mirror at their pale on faces. © and crullers”, ordered the Englishman naming the diet of all those who wander along the roads of America, and pick up their food like the sparrows where they can ‘am and eggs,” said Hill “Ham and eggs and French fried and coffee,” said Blackie. “Ham and eggs,” said Ramon, is a muffled voice ‘THE restaurant proprietor, a fat, cheerful man in a white apron, had been counting bills at his cash register and talking crops with a young farm “hand in overalls. He locked the register with sharp snap and took their orders leisurely, the while guessing their status with his shrewd eyes. He tepeated the orders into the little cubby hole leading to the kitchen. “Solitary confinement, eh what?” Blackie said to the Fnglishman, pointing at the forlorn, middle-aged face of the cook that peered out of the cubby hole and repeated the orders as if in a voice from the tomb. Neither Brown nor the others an- swered, but waited with grim pa- tience for their food. When it came, they wolfed it down rapidi~. as if someone were watching over Blackie could not be still, however. “This is better than the damn beans and rotten stew every day at the other hotel,” he muttered. “Real ham and eggs! Oh, boy!” Brown looked at the clock. It was just noon. “I guess the boys are having their grub now,” he said. “Yes, there goes the whistle. Gosh, you can hear it all the way over here!” The Prison Whistle Yes, it was the prison whistle, the high whining blast like the ery of some cruel, hungry beast wf prey. rising and falling over the little town. and the flat corn-lands, the voice of the master of life, the voice éf the god of the corn-lands. The four prisoners in this restaurant knew that call well; and everyone in the town and everyone living on the corn-lands knew it as thoroughly as they did. “Look,” said Blackie, pointing through a window behind them, “you can just see the top of the prison walls from here. Who would have thunk you could see it so far?” The men turned from their food stare gloomily, while the fat pro- prietor hid a knowing smile behind his curled moustaches. “Two thousand men in hell,” said. Jones quietly. “God, is it worth while? Twenty-five of our boys still in there, ninety-six still in Leaven- worth! “Jim Downey's got fifteen more years to go; so has Frank Varro- chek, Harry Bly, Ralph Snellins and four more,” said John Brown quietly, piercing with his deep blue eves thru all the distance. “And Jack Small has consumption; and George Mulvane is going crazy— Hill, do you think we'll ever get ’em out alive?” Ramon suddenly became hyster- ical. He stood up with brandished and shook them at the distant pri- son, quivering with the rage of 5 years of silence. His olive face darkened with blood, and locks of his long raven-black hair fell in his eyes, so that he could not see, He flamed into sudden Latin elo~ quénce. “Beasts!” he cried, in a choked furious voice, “robbers of the poor, murderers of the young; hangmen, capitalists, patriots; you think you have punished us! You think we will be silent now and not speak of your crimes! You dirty fools, you can never silence us! You can te~ in. prison for all our lives——" ~~ 4 “Oh, Ramon.” Blackie — cried, pushing him back into his seat, and patting him soothingly on the shoulder. “Easy easy! We all feel as sore as you do, Ramon, and we hate just as hard. By God, how we hate them. But easy now, old~ timer, easy!” . - — 'THE others helped quiet the nerve- wracked young Mexican, and he finally subsided and sat there with his face between his hands until they had finished their food. Th the four paid their check to the discreet but amused fat and went into the street on way to the railroad station, trying again to appear casual and uncon- cerned. At the next corner another police- man was lounging against a window, and it was with an that each of the freed n his vacant eye. They and walked by bra still found it hard to they were really free. i i try. it is so far, itself not in the bourgeois. word. . eas Mh